© Rama Knight

I first saw the award-winning violinist Madeleine Mitchell on television in 1979, when I was nine. At the time she was one of the rising stars at London’s Royal College of Music, and the leader of its orchestra. Since then, she has had the most varied of professional careers, initially joining Sir Peter Maxwell Davies’s (1934–2016) ground-breaking group of 6 players, The Fires of London in the mid-1980s, at the same time as winning prizes giving her solo recitals and concerto performances in Europe. She toured and recorded with the Michael Nyman Band, before founding the London Chamber Ensemble in 1992 for a performance of Messiaen Quartet for the End of Time with Joanna MacGregor which they went on to perform at the BBC Proms in 1996 and record. In 2006 Madeleine was asked to put together a chamber music album of the music of William Alwyn for Naxos and in 2019, Madeleine and the LCE released an album of the Chamber Music of the Welsh composer Grace Williams (1906–77), to great acclaim.

Simultaneously, Madeleine’s career as a soloist has been equally illustrious, as concerto soloist and in recitals, on radio and television, and on numerous recordings, including a series of highly acclaimed albums: British Treasures (2003), In Sunlight: Pieces for Madeleine Mitchell (2005), the popular Violin Songs (2007), FiddleSticks (2008, an ACE award-winning collaboration with percussionists ensemble bash), and Violin Muse (2017). In this strand of her catalogue, she has often showcased new, neglected, or previously unrecorded works.

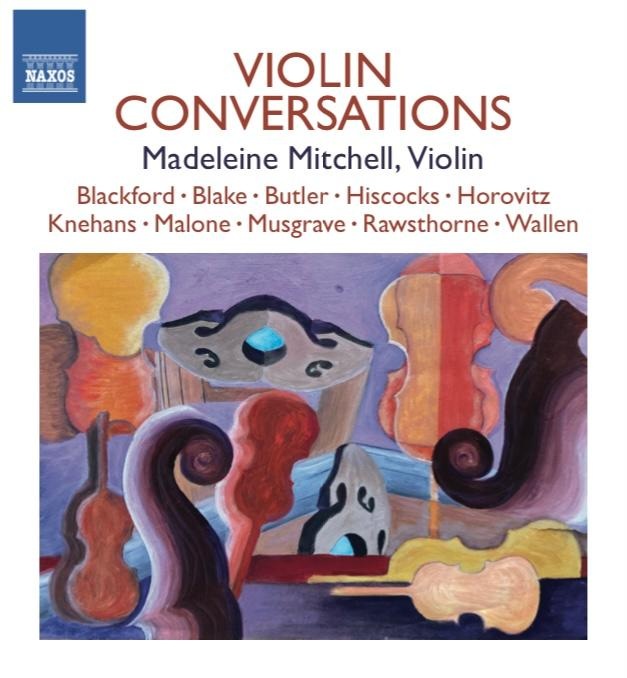

Her terrific new album, Violin Conversations, released by the Naxos label on 23 June 2023, is no exception. It assembles two rarely recorded violin sonatas (by Alan Rawsthorne, and Thea Musgrave) with a programme of approachable newer compositions for violin and piano, by Douglas Knehans (a pupil of Musgrave’s), Errollyn Wallen, Howard Blake, Martin Butler, as well as solo pieces by the late Joseph Horovitz, Wendy Hiscocks and Richard Blackford, and a piece for violin and tape by Kevin Malone.

I spoke to Madeleine on Zoom on the eve of the album’s release to discuss all of its musical conversations and connections, and to look back and indeed forward at her varied career. She shares her memories of the remarkable Yehudi Menuhin (1916–99), of the creation of her Red Violin Festival – a celebration of this most versatile of instruments – and her surprising connection to the cinematic output of David Bowie. And plenty more besides.

We also discuss a concert she was about to perform with her London Chamber Ensemble, which took place in London on 29 June 2023. The programme comprised Franz Schubert’s Cello Quintet (his only string quintet, written in 1828) – which she tells me she had the honour of performing with Norbert Brainin (1923–2005) – and the newly recovered original version of Herbert Howells’ String Quartet No 3 (In Gloucestershire), written in 1916–20, but long thought to have been lost. (A later version, from 1923, has survived.)

But we begin at the beginning with the question I usually ask: the music she first heard when young. We hope you enjoy our violin conversation.

—-

MADELEINE MITCHELL

I heard just classical music at home. My mother was an amateur pianist and Welsh, so came from the singing tradition. She continued to play the piano in her nineties, and we used to play piano duets, even one of the last times I saw her… when she was 96.

My parents were never pushy or anything like that, but they had the radio on: Radio 3 or the Third Programme as it was called then. I remember at my very ordinary primary school in Essex, standing up in class, and saying, ‘I don’t like Dave Clark Five, I like Mozart!’

I started the piano when I was six and loved it, as I did music theory. When I was ten, I played the Mozart Fantasia in D minor from memory for the whole school. It was an absolute thrill even though my friends weren’t really from that sort of background. My mother said to me, ‘If you played an orchestral instrument, you could have fun making music with the other children.’ And I thought, ‘She’s right and I’d like to play the violin.’ Fortunately, you could learn violin free at school.

—-

FIRST: EDWARD ELGAR: Violin Concerto in B minor

Yehudi Menuhin, soloist, London Symphony Orchestra, conductor Edward Elgar, 1932 recording

Extract: 1st movement: Allegro

MADELEINE MITCHELL

My dad was an engineer and was very skilled at that sort of thing. He had a reel-to-reel tape recorder, which was also how I heard quite a bit of music. One recording he had on reel-to-reel was the legendary recording from 1932 of Yehudi Menuhin, aged sixteen, playing the Elgar Violin Concerto with Elgar himself conducting – and I was really taken with this. Unlike most of the great composers, who were keyboard players, Elgar was a violinist, and he wrote this work in 1910 for Fritz Kreisler.

Amazingly, my local library, the Havering Central Library had the sheet music for it, so I borrowed it. And at the same library I also found this book that had been discarded, which was called Theme and Variations by Yehudi Menuhin (published 1972). It wasn’t just about music. There were chapters on architecture and Indian music and organic food… It was fascinating.

JUSTIN LEWIS

The impact that Menuhin had is almost impossible to overstate. When I was a child in the 70s, everybody knew who he was. He appeared on Morecambe and Wise, he guested on Parkinson (BBC1, 18 December 1971) – which I would not have seen at the time – but I saw the clip of him and Stéphane Grappelli, much repeated since, on other programmes. (The two made a return appearance on the Parkinson show on 17 November 1973.)

MADELEINE MITCHELL

Playing Tea for Two? Yeah. I loved Grappelli. He would be in my top ten violinists along with Heifetz and Oistrakh and Kreisler. But with Menuhin, I think it’s the emotion in his sound that Menuhin gets – in German they call it “innigkeit” – inner feeling and it’s very moving.

I once gave a recital in Russia at the St Petersburg Festival of British Music, and afterwards the agent came up to me and suggested I play the Elgar Violin Concerto. I thought: ‘Wow! First of all, you know it, and secondly, you’re asking me to do it!’ So she sent me off to a place called Samara, one and a half hours east of Moscow by plane, where Shostakovich wrote his Seventh Symphony, and where they all went during the Second World War because it was safer than Moscow.

This was in the February, and I imagined it would be so cold there, but everything was very well heated. There was a very good conductor called Ainārs Rubiķis, who had won the Mahler Competition and the orchestra were fabulous. And after the first rehearsal, the flautist came up to me and she said, in broken English, ‘We didn’t know this piece. We knew the Elgar cello concerto. But we love this violin concerto. It’s so emotional.’ I said, ‘You’ve absolutely got it. That’s exactly what Elgar said. He said, “It’s so emotional, too emotional. But I love it.”’

And that’s what I love. And that’s what Menuhin gets in the music. When I heard his recording, I got the music as a teenager and tried to play the second subject, working out what fingering Menuhin did. Years later, at the Royal College of Music, I had lessons with Hugh Bean (1929–2003), a student of Albert Sammons (1886–1957), who worked closely with Elgar (1857–1934), and when I came to learn the concerto properly, to perform it, in 1993 I asked Hugh Bean if I could play it for him and I remember him saying, ‘Oh Albert said that Elgar said’, and I thought, I must write this down, this is really important. In fact, Hugh used more simple fingerings in places, in a more English kind of way. Menuhin loved England, he lived in London, founded the Menuhin School and became Lord Menuhin, so he took up those English ways, while there was that Jewish/Russian/American thing going on as well. Fascinating.

JUSTIN LEWIS

These connections and conversations, stretching back into history, are so striking. But you have another connection with Menuhin, because in the 1990s you started a festival, right?

MADELEINE MITCHELL

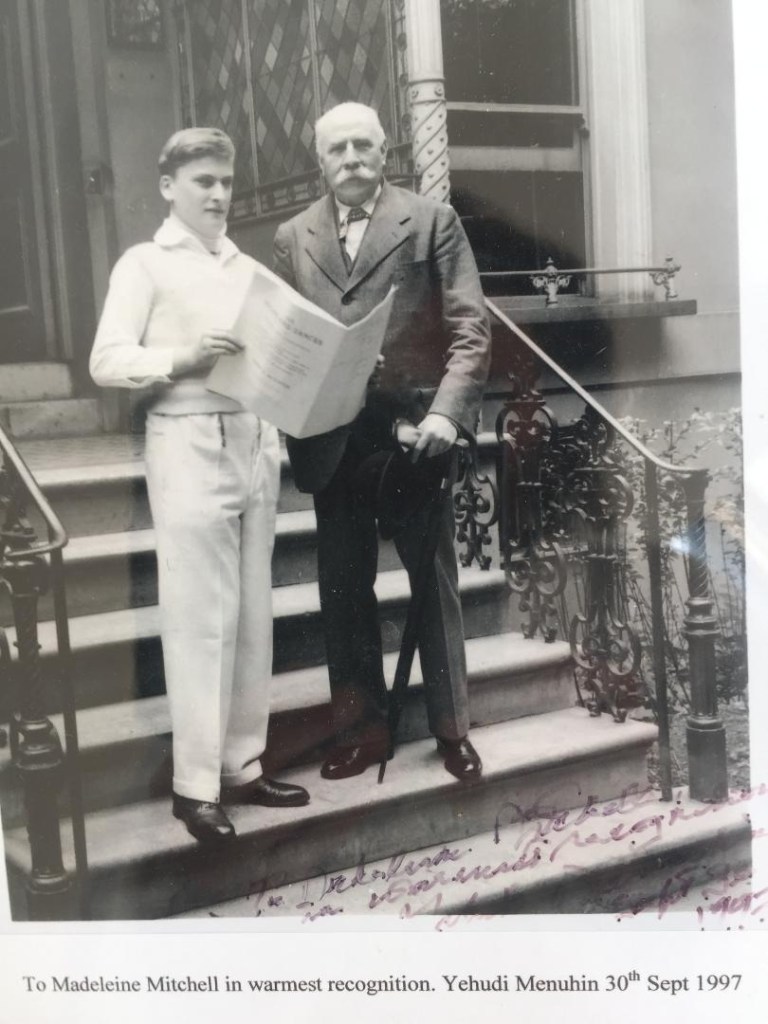

Yes, towards the end of his life, in 1997, he agreed to be the Patron of my Red Violin festival, [a celebration of the violin and violin playing across different genres] – Gwyll Ffidil Goch in Welsh, a ten-day festival in Cardiff – which was dear to his heart. I was thrilled. I was invited to Menuhin’s studio in central London to record an hour’s interview for the BBC and because he couldn’t make the launch, he did this lovely video message – you can see it on YouTube.

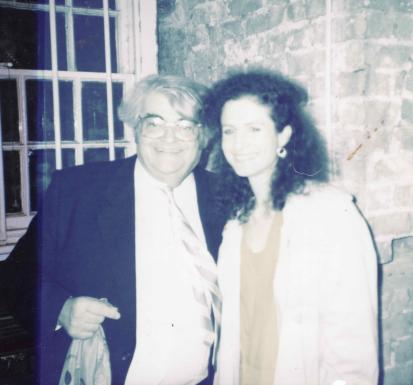

Madeleine Mitchell and Yehudi Menuhin: Red Violin Festival, 1997

MADELEINE MITCHELL

I had with me the photograph of him when he was 16, in 1932, on the steps of Abbey Road [which had in fact only just opened, as EMI Recording Studios]… having just recorded this concerto… And he signed the photograph and then he embraced me. Very touching. So it sort of came full circle, it was a huge endorsement for my creative idea, which I’m keeping going. We’re doing another Red Violin festival in October 2024 in Leeds.

Photo of Yehudi Menuhin, age 16, with Sir Edward Elgar, after their legendary EMI recording of the Elgar Violin Concerto, on the steps of Abbey Road. Signed by Menuhin for Madeleine Mitchell when she interviewed him at his home, for the BBC Radio 2 documentary about her Red Violin festival of which he was the Founder Patron.

Photograph supplied by MM with Yehudi Menuhin, 1997, Red Violin, credit ITN

JUSTIN LEWIS

Tell me, then, about how you originally came up with the idea for the festival.

MADELEINE MITCHELL

The title came from the titles of the paintings, Le Violon Rouge (The Red Violin) by Raoul Dufy (1948) and Jean Pougny (1919). My mother was more of an artist than a musician and so we were surrounded by her art as well as reproductions of fine paintings at home such as Cézanne, and I collected cards of violin paintings –Picasso, Chagall and Matisse as well as Dufy etc.

I had the idea at Christmas 1994 while all was quiet. I had just played in The Soldier’s Tale – L’Histoire du Soldat – by Stravinsky, this tale of the soldier who sells his soul, represented by the violin, to the devil. Obviously the violin is the foundation of the orchestra and it struck me how the violin had inspired not only composers in all sorts of music but also painters and writers etc and I thought how wonderful it would be to have a festival celebrating the violin across the arts.

JUSTIN LEWIS

It’s such a magical, versatile musical instrument. It not only has a different voice in all these different genres of music, but I can remember as a child thinking that a group of orchestral violinists made a sound that felt different from a solo violinist sound. I know all instruments have that ability to some extent, but the violin for me does it more than most. But how did you progress on violin and piano after your early lessons?

MADELEINE MITCHELL

I had shared lessons with a peripatetic music teacher, and was loaned a very ordinary school violin. But when I was eleven, I had one year of private lessons, and was awarded an Exhibition to the Junior Department of the Royal College of Music, and got in on piano first study. But I think they thought I was very promising on the violin. So then I became joint principal until I was eighteen. And when I got a scholarship at the Royal College of Music (on a violin for which my parents paid £20), they said, ‘How are you going to have time for both and the graduate course?’ So at that point I decided to do piano second study, and then I studied viola as well at College.

JUSTIN LEWIS

I was a flautist when I was growing up. I was fascinated by the violin as a child, even though I never learned to play it. It always looked far too complicated! [Laughter] I couldn’t imagine finding the level of coordination that’s required.

MADELEINE MITCHELL

It’s very difficult!

—-

Violin Conversations: Cover painting by Evelyn Mitchell née Jones (1924–2020)

JUSTIN LEWIS

Your new album, Violin Conversations, really does cover a great deal of ground. How did you decide on its running order?

MADELEINE MITCHELL

It happened gradually. In the back of my mind was my duo partner, the pianist Andrew Ball (1950–2022). I really loved playing with Andrew. We made four albums and we did a lot of broadcasts and concerts for twenty years in a whole range of repertoire. He’d play the César Franck Violin Sonata marvellously, but also new music too. A very intelligent, lovely person. And he got Parkinson’s; absolutely tragic, so couldn’t play anymore. It was such a loss. But while he was still alive, I thought, ‘We’ve got this recording of this live broadcast of the Alan Rawsthorne Violin Sonata’ [broadcast, BBC Radio 3, 11 July 1996] which went very well. It’s a good piece, but it’s hardly ever been recorded, as opposed to another recording of a Brahms sonata or the Ravel, two other favourites we did in the same concert.

Meanwhile, I had put Thea Musgrave’s Colloquy into my programme: ‘A Century of British Music by Women’ in 2021, only to discover there was no available recording. It was recorded at the time of the première in 1960 by the performers who recorded it for vinyl, but it’s not available, and it wasn’t reissued. I thought, that’s a strong piece by an important composer, we really ought to record that.

So we’ve got two 20th century classics. In fact, I didn’t actually know until I researched it that the Musgrave and the Rawsthorne were both premiered at the same concert, the Cheltenham Music Festival in 1960, even though the Rawsthorne had been written in 1958, two years earlier.

JUSTIN LEWIS

The Musgrave and Rawsthorne has an extra neat connection with this series, in that the violin soloist for both was Manoug Parikian, whose son Lev was First Last Anything’s very first guest!

MADELEINE MITCHELL

I knew Manoug slightly, but I actually did play with Lamar Crowson, who was the pianist.

JUSTIN LEWIS

Let’s talk about some of the more recently composed works on Violin Conversations, then. Many written specially for you.

MADELEINE MITCHELL

I knew all the composers. I met Richard Blackford in 2003 at the centenary celebration of the Royal College of Music’s Tagore Gold Medals, the award for the most distinguished student of the year. We won it in different years, but that’s how we met and became friends. During the first lockdown in 2020, when I went back to completely solo violin – there was nothing else you could do – I agreed to contribute to a charity album, Many Voices on a Theme of Isolation, to help raise money for Help Musicians UK and I asked Richard, who sure enough, wrote me, very quickly, a solo violin piece called Worlds Apart, to pay homage to those people who were not able to be together because of the lockdown. It’s a haunting little piece. Three minutes. But I’ve re-recorded it for Violin Conversations, to get better quality.

A lot of the pieces were gifts. Martin Butler also wrote me a piece that grew out of lockdown, because composers were quite active during that period. So he wrote me Barcarolles; it just appeared out of the blue as a present, and he lives near the sea in Sussex, so the wateriness of it… it all goes together.

JUSTIN LEWIS

Errollyn Wallen’s Sojourner Truth also has a connection with lockdown, doesn’t it?

MADELEINE MITCHELL

I met Errollyn twenty years ago. We became friends, I’d see her from time to time, and about three years ago, she wrote me a piece, Sojourner Truth, commissioned with a grant from what was the RVW Trust, now the Vaughan Williams Foundation. He was a very generous composer, who bequeathed a lot of his estate to setting up this foundation for other British composers, for new music, and for neglected composers – like Grace Williams (one of his former students).

I went to stay with Errollyn at her lighthouse recently in the north of Scotland, and when I gave the première of Sojourner Truth in March 2021, she was in her lighthouse during lockdown. I was able to rehearse with a pianist in London, two metres apart, while Errollyn was on FaceTime, hearing it and telling me things. So it was really wonderful to finally meet up with her and play it with her. It took a bit of persuading because she said she was a bit out of practice, but you know, it was her particular style of a jazzy singer-songwriter. She probably wrote it at the piano and then she was able to say things to me – ‘take more time here’, or whatever it was. I found it really interesting.

JUSTIN LEWIS

I was watching the video conversation you two had about Sojourner Truth, in which you discuss one of the greatest things about commissioning a new composer – you can directly talk to the composer!

MADELEINE MITCHELL

It’s a no brainer, isn’t it? It’s wonderful! You can just ask some things, and they’ll tell you things, and they’re very happy to do so. And I’m so pleased to have been able to commission Errollyn Wallen, to celebrate this extraordinary woman, Sojourner Truth (c. 1797–1883), the American abolitionist. Who I had not heard of. What an extraordinary life. You know, it’s great that that she will live on in perpetuity in the title of that piece and on this recording.

Errollyn Wallen and Madeleine Mitchell perform and discuss Sojourner Truth.

JUSTIN LEWIS

I’m sure one reason I’m increasingly immersed in classical music more profoundly, admittedly belatedly in life, is the way that it now feels much more inclusive, in a way it didn’t used to. How have you seen this change over your professional career, that awareness of diversity?

MADELEINE MITCHELL

It’s got a lot better, for sure. There’s much more focus on it on it now. With women composers, it’s very important to still retain the quality, so it’s not just tokenism for the sake of it. But it’s good that composers like Grace Williams, who were rather self-critical and didn’t push themselves forward and didn’t really have a powerful publisher, are now getting the recognition that they deserve.

JUSTIN LEWIS

Tell me about some of the other composers on Violin Conversations.

MADELEINE MITCHELL

Joseph Horovitz, who died last year, was a brilliant lecturer in my first year at the Royal College of Music, who became a friend. Dybbuk Melody was a piece he gave me on a piece of manuscript, but it hadn’t been recorded.

JUSTIN LEWIS

Wasn’t it written for a production of S. Ansky’s The Dybbuk (BBC1, 24 February 1980)?

MADELEINE MITCHELL

It was, you’re absolutely right, it was for the closing credits. A very Jewish piece. So I had that. Wendy Hiscocks, the Australian composer, had these two pieces which hadn’t been recorded. One is Caprice – in a slightly Vaughan Williams-y idiom, if you like. There’s Kevin Malone’s Your Call is Important to Us, a piece for violin and tape. And while Thea Musgrave is a sort of granite-like grit in the oyster in the middle of the album, you have the spacious piece by her former student Douglas Knehans (b. 1957), Mist Waves, which he wrote for me in 2019.

JUSTIN LEWIS

And to round off, there’s a collaboration with Howard Blake. There’s quite a story behind how you first met him!

MADELEINE MITCHELL

I met Howard in 1982, the year that he composed The Snowman, so I was very young then. I was invited to audition for the part of the young violinist in the film The Hunger, with David Bowie and Catherine Deneuve. I went to the home of Tony Scott, the film’s director and Howard Blake was there as the Musical Director. Unfortunately, I wasn’t quite young enough, or didn’t look quite young enough to play the 13-year-old girl in the film. But Howard really liked my playing at the audition, so unbelievably, he invited me to record two solo tracks at the legendary Abbey Road Studios, for the film. So although I’m not visually in the film, my playing is: the violin part of the slow movements of the Lalo and Schubert E flat piano trios. Just me and Howard in this huge Studio 1 at Abbey Road. It was incredible.

Years later, I saw Howard again at the Chester Music Christmas party, and he said, ‘I’ve reworked my Violin Sonata, which I wrote years ago. Would you like to come and try it?’ So I did and we worked well together. His music has a lot of jazz influence, which appeals to me, and we ended up making an album of this Violin Sonata for Naxos [2008], along with his Penillion, and an arrangement he made for us of his of Jazz Dances for violin and piano.

We then did lots of concerts together. And at lunch, he’d tell me all these stories, how he was in the studios in the 70s, playing for Eartha Kitt. And you know, he has a very particular style of playing the piano. He arranged Walking in the Air for me as well, in 2010, but then he came up with The Ice Princess and the Snowman, a really beautiful piece, and we originally did it for a Classic FM live video at St John’s Smith Square, where he talks about it as well:

The Violin Conversations album is mostly new music, but what strikes me – compared to 40 years ago – is it’s much wider and broader, different styles being more readily accepted. So, Howard Blake’s is unashamedly tonal romantic music, and the Horovitz Dybbuk Melody and the Wendy Hiscocks Caprice – it’s all tonal music really. There was a time when all that was shunned and it was out of fashion… But what’s happened during those four decades is there’s a wider brief for contemporary music where all sorts of things are accepted: violin and tape, electronics, as on the Kevin Malone, or something that you might say is quite traditional – Errollyn’s piece is based on a slave song – but written very recently.

JUSTIN LEWIS

One of the best things about the digital world is how we can connect up all this material. New music, or even just previously unheard music, is easier to find.

MADELEINE MITCHELL

What occurs to me, joining up the dots of this conversation: Yehudi Menuhin seemed quite an elderly, ethereal sort of person, but actually he really had his finger on the pulse. He said to me – and this was 30 September 1997, just before the Red Violin festival: ‘Young people have a short attention span. It’s good what you’re doing because you know you’re giving them the taste of jazz and folk fiddle and classical, and pictures.’ And this was 1997, before we all had mobile phones. With this album, there are four pieces that are three minutes long. People can give it a try. It doesn’t require a huge investment, you know. Richard Blackford – three minutes; Wendy Hiscocks’ Caprice – three minutes. Howard’s piece is four minutes.

JUSTIN LEWIS

We’ve all got four minutes to spare to listen to something.

MADELEINE MITCHELL

And one movement of the Rawsthorne, even. I mean, I think it’s a spectacular opening. That wonderful cluster on the piano, very dramatic. And then this soaring violin line. It’s very arresting. I hope people will respond to it.

—

JUSTIN LEWIS

Obviously you’ve been doing commissions from contemporary composers a long time, from the mid-80s, I think. How does that commissioning process work? Do people come to you; do you go to them?

MADELEINE MITCHELL

It’s a mixture. I wasn’t just a kind of virtuoso violinist when I was growing up, I was an all-round musician in lots of ways: I loved music theory, I loved harmony, and I would write little pieces myself when quite young, thinking maybe I’d like to be a composer. Then the violin took over, and I just loved the expressivity of its sound.

But composing was in the back of my mind somehow. In the early 1980s I was asked to lead the contemporary ensemble at the Aspen Music Festival in Colorado when I had a fellowship there as a student, so I met Philip Glass and Ned Rorem there. And when I came back from America, I was invited to audition for a position in Sir Peter Maxwell Davies’s very prestigious group, the Fires of London. It was a very tough audition. Two rounds. I had to play viola, as well, and had to play from memory a big violin solo of one of his pieces: Le Jongleur de Notre Dame (1978). So I was invited to join the Fires of London, and it was a baptism of fire.

JUSTIN LEWIS

What do you think you learned from Peter, in terms of ensemble playing as well as solo playing? Because that must have been an incredible thing to be doing, those sorts of performances.

MADELEINE MITCHELL

It was, it was. It was absolutely extraordinary. I really liked Max – we always used to call him Max. He asked me to look over the manuscript of the violin concerto he was writing for Isaac Stern and I stayed friends with him until the end of his life; he always used to call me ‘love’ and he even signed my daughter’s trumpet music to his Sonatina, not just with a signature but a message thanking her for playing it! But one of the first things I did with him was a five-week tour of the States with The Fires of London in 1985 for Columbia Artists Management, with Max conducting. We started off in Toronto, we sold out Lincoln Center. We sold out UCLA in Los Angeles, we played at Kennedy Center in Washington. We were on the cover of Time magazine. We had receptions with the British Ambassador… It was really amazing.

Some of the music was absolutely fiendish to play; I remember the cellist in the group said to me, ‘I just look at the music and work out where the beats go’, because it was very complex. It was a sort of intellectual challenge, which I did actually quite enjoy, just to work out how it fitted together.

And Max had these amazing eyes, like a fire, talking of Fires of London, now I come to think of it. He may not have been a born conductor, but just to have him there – there was something about the energy. And of course I was the new girl, and I was joining this incredible group. The clarinettist in the group David Campbell remained friends with me, and I invited him to join me for my first recording, which was the Messiaen Quartet for the End of Time, with Joanna MacGregor (piano), and Christopher Van Kampen, marvellous cellist, who sadly died.

Meanwhile, I’d won some competitions and was very busy, going off to play the Brahms Violin Concerto for the first time. All this was happening at the same time. But it was really through Max that I met composers, including Brian Elias who wrote a piece for the Fires called Geranos (1986), for the six of us.

One competition I won was the Maisie Lewis Young Artist Award from The Worshipful Company of Musicians which gave me a South Bank recital and as well as playing Brahms and Bartok I thought it’d be good to commission a piece, so I commissioned Brian Elias for my début and his ‘Fantasia’ has worn well. I met other composers like James MacMillan, who after I commissioned a piece – Kiss on Wood, wrote me a second piece as a present – A Different World (both on the album In Sunlight: Pieces for Madeleine Mitchell, along with Elias Fantasia). And I suppose it’s snowballed, because I’ve met lots of composers and they come to me, and sometimes, out of the blue, they write me pieces as presents.

JUSTIN LEWIS

What new pieces are you planning to perform or record next?

MADELEINE MITCHELL

The composer George Nicholson heard me play at Sheffield University in 2019, and wanted to write me a piece, which I thought would be a short piece. But no! It’s a seven-movement Suite for solo violin, which I’m premiering in November at the St Andrew’s Music Festival in Sheffield. I’ll have to work at that – it’s a big piece. And there have been a couple of concertos: Piers Hellawell wrote Elegy in the Time of Freedom me in 1989 which I premiered at the Queen Elizabeth Hall in 1992 and Guto Pryderi Puw’s Violin Concerto, Soft Stillness, which I recorded with the BBC National Orchestra of Wales in 2016.

But coming back to this business about wanting to be a composer, I like to do arrangements. I don’t have time or inclination to compose – I’m too busy with playing – but I do like arranging, it’s the next best thing. And I also like creative projects. I won a Royal Philharmonic Society Enterprise Award for my proposal to combine art with music in an intelligent, relevant way with specific reference to the Victoria & Albert Museum’s exhibition of Carl Fabergé (1846–1920), From Romance to Revolution. My quartet gave the performance in January 2022, coming out of lockdown, and I made a film, with the images of Fabergé (courtesy of Wartski, Chairman Nicholas Snowman OBE), combined with music of the time and place.

Fabergé came to London in 1903. And then, of course, there was the Revolution in 1917. So we started off with the Russian music from St Petersburg – Borodin and contemporaries – but then I remembered that there was this Herbert Howells’ Luchinushka, which is a Russian Lament from 1917. It’s originally a violin and piano piece, which I’d played a lot all over the place, Sri Lanka, California… And I got permission from the Howells Trust to arrange it for string quartet. So that’s on the film, it’s on YouTube, the Fabergé film. They heard that, they liked it, and they’ve asked me to record that now with the original Howells Quartet no.3 we just premiered with my London Chamber Ensemble. So that’s my next project…

Madeleine Mitchell on Music & Art

V&A Fabergé and Anglo-Russian Quartets, London Chamber Ensemble

(Fabergé images in the above film courtesy of Wartski, Chairman Nicholas Snowman OBE)

Herbert Howells: Luchinushka (arrangement)

Madeleine Mitchell live with Rustem Kudurayov, piano in Firenze

JUSTIN LEWIS

And speaking of Herbert Howells, there’s been quite an exciting find of one of his works! Tell me about that.

MADELEINE MITCHELL

Yes, we have been invited, as the London Chamber Ensemble – which lately is really focused on the core string quartet – to give the première performance and recording of Herbert Howells’ String Quartet No. 3, In Gloucestershire, which was thought to be lost.

JUSTIN LEWIS

The score was thought to be lost?

MADELEINE MITCHELL

It was left on a train in 1916 and never recovered – and he rewrote it some years later. But it’s not the same; The third movement is most similar, but the rest is really different. The early string parts were found recently, and I was very pleased that the Howells Society got in touch and asked, ‘Would your group like to do this?’ Yes, of course!

—-

LAST: AMADEUS QUARTET: FRANZ SCHUBERT: String Quintet in C Major, D.956

Extract: II. Adagio

MADELEINE MITCHELL

Coupled with the Howells première, we’ll also be playing the Schubert Cello Quintet. The concert is for the Schubert Society of Great Britain, a little bastion of culture in London W2, near Paddington. [JL: The concert took place on 29 June 2023, at St James’s Sussex Gardens. It was a superb afternoon of music, and it was a privilege to be there.] The Cello Quintet is interesting because, years ago, I went to the International Musician Seminar as a young professional violinist, and the idea was that young musicians would spend a week playing with veteran musicians. I had the honour of working next to Norbert Brainin, the legendary leader of the Amadeus Quartet, and in a trio with the cellist Zara Nelsova.

Madeleine Mitchell with Norbert Brainin, Prussia Cove, 1993

I loved playing with Norbert – we got on like a house on fire – and years later I was so honoured that he asked me to be the second violinist, to join him for his 80th birthday concert at the Wigmore Hall, which was sold out. He oozed music, he had such warmth and sparkle. I love that group’s playing, and although Norbert wasn’t born in Vienna, the other three members were, and they’ve got that unique Viennese spirit. I find when some of the groups play that piece now… it’s a bit fast, it doesn’t quite have the space to breathe and sing.

But people have chosen the second movement of the Schubert Quintet for Desert Island Discs, with Norbert Brainin, because it’s so special. So I wanted to choose that recording as a recent thing I’ve been listening to because we’ve just been performing it.

—-

ANYTHING: BILL EVANS: Everybody Digs Bill Evans (NOT2CD299 – Not Now Music Limited compilation 2009)

Extract: ‘Easy Living’

MADELEINE MITCHELL

I don’t know where this comes from because I don’t think it was particularly part of my home background. But I really got into jazz, I loved jazz when it wasn’t fashionable and I was a member of Ronnie Scott’s and the 100 Club when I was in my twenties. I love Grappelli, of course, but I particularly like piano jazz. You obviously listen to a lot of classical music, and for my leisure and recreation, I go to art galleries and the opera, but I also like to listen to jazz, so maybe on a Friday night I’ll put on my favourite, which is this double album from Bill Evans, Everybody Digs Bill Evans. My daughter will say, ‘Oh, not again, you know, I’ve got this!’ But then I made a Bill Evans playlist on Spotify.

JUSTIN LEWIS

Which you sent me. I’ve been enjoying that.

MADELEINE MITCHELL

Autumn Leaves and When I Fall in Love. I can’t put my finger on why I like it so much. It’s subtle. I love the chords. I love the sound. It’s sophisticated. It’s quite romantic as well. I play a lot of new music, but actually I’m a real romantic. I absolutely love playing Brahms and Bruch and maybe that’s what I like about this music I’ve selected. I started as a pianist, I really like the piano so maybe that’s a contributing factor.

—-

MADELEINE MITCHELL

Another composer who relates to several pivotal moments in my career is Alban Berg. I first heard his Die Nachtigall, from his Seven Early Songs, on an LP which was chucked out of the same Romford library as the Menuhin book. It was an anthology of Pierre Boulez favourites, and it included this, performed by Heather Harper with an orchestra. Years later, in 1992, I arranged this for my début at the Huddersfield Festival of Contemporary Music, and my first concert with Andrew Ball for a late-night recital programme I devised about Night Music. The lighting was by Ace McCarron, the original lighting designer for The Fires of London, then Music Theatre Wales.

And there’s another Fires of London connection! Max and Harrison Birtwistle – two of the Manchester Five – were influenced by the Second Viennese School, of which Berg and Arnold Schoenberg were the key players, with Anton Webern. Max and Harry originally co-founded The Pierrot Players in 1967 – with the same instrumentation as Schoenberg’s Pierrot Lunaire (which happened to be the first piece I ever performed for the BBC), plus percussion, which became The Fires of London in 1971.

But also, the first opera I ever saw was Berg’s Wozzeck at Covent Garden when I was sixteen; a friend from my local Youth Orchestra had just got a job in the Royal Opera House violin section and invited me. I was bowled over by it and I have loved opera ever since.

—-

JUSTIN LEWIS

You were in the Michael Nyman Band for a while, weren’t you?

MADELEINE MITCHELL

That’s right. A couple of years after the Fires of London disbanded in 1987, I was asked if I would join Music Theatre Wales Ensemble as their principal violinist because it sort of naturally grew out of the Fires in a way. One of the pieces we did was Michael Nyman’s The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat in Swansea, at Taliesin Arts Centre. Michael came all the way to that theatre to hear the performance and he said he liked my gutsy playing, and asked if I would come and play in his band. So I did, for a couple of tours, and got to know him really well, and then he arranged three pieces for me called On the Fiddle, which I recorded for the In Sunlight album. And then he wrote two more pieces for me, Taking It as Read on my Violin Muse album.

JUSTIN LEWIS

You need to write a memoir to cover this career!

MADELEINE MITCHELL

I’ve never specialised. I don’t like the idea of musicians or people being put in boxes. You know, you tend to get known for the premières because they’re more newsworthy than you playing your favourite Beethoven Sonata (for me no.10 opus 96) – but that sonata is the one which is what inspired Geoffrey Poole to write his Rhapsody for me. It all came out of a mutual love of that piece and wanting to play it together.

—

JUSTIN LEWIS

I think I saw you on television when I was a child. Could you have been on the schools programme, Music Time (BBC1, c. 1979)? Which I think Chris Warren-Green did as well.

MADELEINE MITCHELL

Yes, it’s very interesting. A lot of people saw that because it went out live. I was a student, and I was asked by the Royal College of Music to go and do this. And I remember exactly what I had to play, and exactly what I had to say. I had to play a solo violin bit from Saint-Saëns’ Carnival of the Animals, just a few bars, and I had to say, ‘I can make sounds which slide up and down.’

JUSTIN LEWIS

Oh yes, the donkey. [Carnival of the Animals, Part VIII. People with Long Ears]

MADELEINE MITCHELL

I wasn’t nervous about the playing, but I was a bit nervous about the words because it was going out live and I wasn’t used to doing it. I remember going into a telephone box to practise my lines to make sure I had them fluent. When I became a professional and I would start talking to audiences, they would give me feedback that they really liked that. And gradually I became more and more confident and fluent about the speaking so that I’ve got to love talking to audiences.

When I was in charge of the Graduate Solo and Ensemble Performers at the Royal College of Music, I instigated seminars where I would coach the students about the whole performance including walking on, bowing and speaking to the audience. Sometimes they didn’t have English as a first language, but I’d say, ‘practise speaking slowly and clearly’, just as my parents used to say to me before I went on the radio. It is very important to do that.

Sometimes if you’ve started playing at an early age and grown up with it, you forget that some people don’t have that, and it’s lovely to help them get into it, so they have a human connection. Even if they don’t know how to play the violin or they don’t ‘understand’ the music, it doesn’t matter because, as I always say to them, you just have to listen. You don’t have to be able to read music or know the history, because if you’re open to it, it’s about being moved by music, isn’t it? And I feel if that’s what I can do for even one or two people in an audience, then I’ve done a good job.

JUSTIN LEWIS

Yes, I know you can’t always talk to the audience in a concert, but I came to see you and Nigel Clayton play at St John’s Smith Square at Easter, and I really loved the section where you paid tribute to Nicholas Snowman, who had just died, as you introduced the piece written for you in his memory by Michael, Lord Berkeley.

MADELEINE MITCHELL

That audience at St John’s Smith Square was lovely. Straight away, there was a feeling of warmth, and excitement at times. I find often the end of the concert, with the encore, is the best bit.

JUSTIN LEWIS

But I find classical music easier to absorb now. It might just be because I’m older, but I used to feel – maybe incorrectly – there were a lot of formalities, and I feel there aren’t quite as many now. It feels more accessible.

MADELEINE MITCHELL

Maybe now you can go to concerts again you don’t take it for granted. I remember when I premiered Kevin Malone’s Your Call is Important to Us (for violin and tape) which he’d written me, in May 2022, it was soon after the second lockdown and it was such a joy and such a relief to walk out into that concert hall at Manchester University and see a sea of people’s faces. I kept going during lockdown with livestreamed concerts, but it just isn’t the same at the end of a livestreamed concert when you’ve given your all, but there’s no applause and you can’t see anyone. People can send you comments and things, but it isn’t the same. I think that performing is a three-way process.

JUSTIN LEWIS

I found this really great quote from an American newspaper. It was around the time of The Fires of London touring the States in ‘85. And Peter Maxwell Davies describes this relationship between the composer, the performer and the audience, and how vital that is, no matter how the piece is played.

MADELEINE MITCHELL

I always say this to people when they come up to me after concerts and they say, ‘Oh, I wish I’d kept up with the violin when I was a child…’ – that sort of thing. They’re a bit disparaging about themselves and I say, ‘Look, you’re really important. You’re the audience.’ The audience is a very valued one-third of the triangle, if you like: the composer at the top, then the performers as the conduit, the channel, and the audience not only receiving the music, but also giving back. You can pick up the energy of an audience. It’s very palpable. It’s an exchange.

—-

With Madeleine once more as Artistic Director, The Red Violin festival was again staged to much acclaim, over five days in Leeds, in October 2024.

For further news, information and links on Madeleine’s career and upcoming concerts, visit her website and sign up to the mailing list: www.madeleinemitchell.com.

Madeleine is performing at Leighton House on Tuesday 24 June 2025, London W14, with Julian Milford, piano and Kirsten Jenson, cello. They will be playing Brahms’ Piano Trio in B major op.8, Mel Bonis’s Soir – Matin for piano trio, and salon pieces by Sir George Dyson. For tickets, click here: https://www.eventbrite.co.uk/e/madeleine-mitchell-friends-concert-leighton-house-246-tickets-1233078804899

Madeleine’s Violin Conversations was released on the Naxos label in June 2023. In August 2023, shortly after its release, Ivan Hewett gave it a glowing review in the Telegraph. Read here: https://www.madeleinemitchell.com/is-madeleine-mitchell-the-future-of-classical-music

You can follow Madeleine on Twitter at @MadeleineM_Vln, and on both Instagram and Threads at @madeleine_mitchell_violin. She is on Bluesky at @madeleinemitchell.bsky.social.

Subscribe to her youtube channel at https://www.youtube.com/@ViolinClassics

And her Facebook page is here: https://www.facebook.com/MadeleineMitchellViolinist

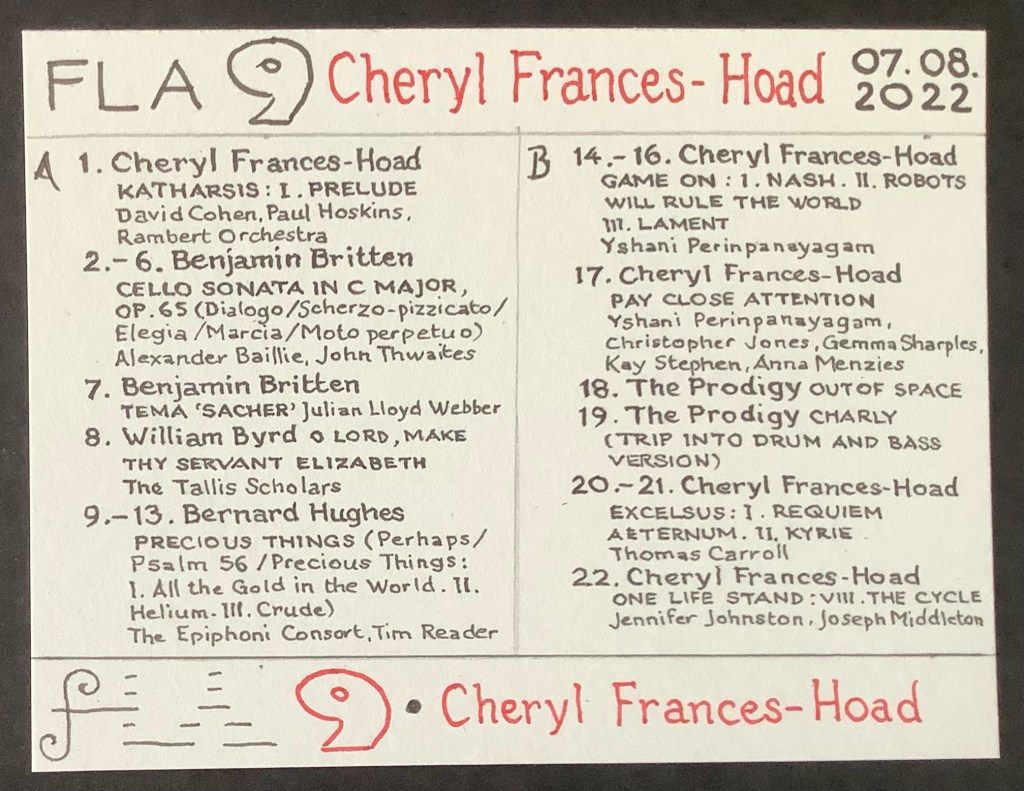

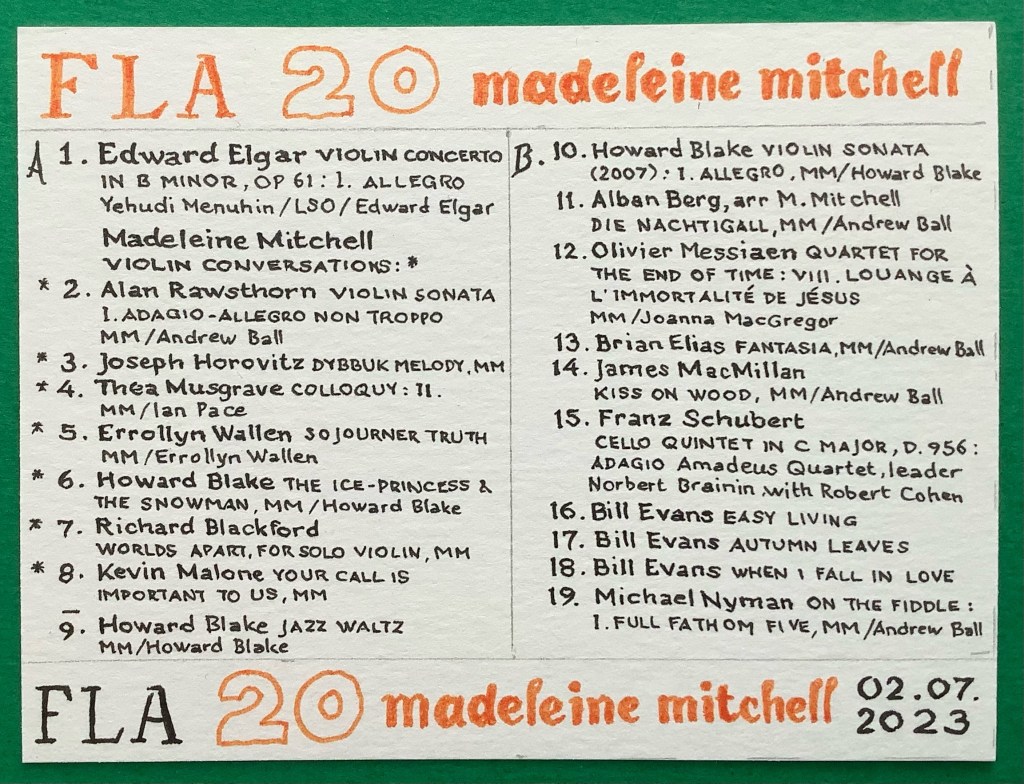

FLA PLAYLIST 20

Madeleine Mitchell

(For the time being, this site and project uses Spotify for the conversation playlists, but obviously I disapprove that Spotify doesn’t pay artists and composers properly, and other streaming platforms are available, as are sites to buy downloads and buy recordings. For consistency, you can also listen to the selections via YouTube (where available), and links are provided in each case, below.)

Track 1: EDWARD ELGAR: Violin Concerto in B Minor – 1st Movement

Yehudi Menuhin, London Symphony Orchestra, conducted by Edward Elgar: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tJQVXr6jvBc

Track 2: ALAN RAWSTHORNE: Violin Sonata: I. Adagio – Allegro non troppo

Madeleine Mitchell, Andrew Ball piano: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=muwwopo3Ays

Track 3: JOSEPH HOROVITZ: Dybbuk Melody

Madeleine Mitchell: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tIxKggZNaTQ

Track 4: THEA MUSGRAVE: ‘Colloquy’: II.

Madeleine Mitchell, Ian Pace piano: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mrdn49VcE18

Track 5: ERROLLYN WALLEN: Sojourner Truth

Madeleine Mitchell, Errollyn Wallen piano: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=r1391EMDUCI

Track 6: HOWARD BLAKE: The Ice-Princess and the Snowman, Op. 699

Madeleine Mitchell, Howard Blake piano: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4mul3zdJnds

Track 7: RICHARD BLACKFORD: Worlds Apart for solo violin

Madeleine Mitchell: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MT5gSlQRsbQ

Track 8: KEVIN MALONE: Your Call is Important to Us for solo violin and tape

Madeleine Mitchell: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MzTFMVn4PNE

Track 9: HOWARD BLAKE: Jazz Waltz

Madeleine Mitchell, Howard Blake piano: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WXR_76y6UF4

Track 10: HOWARD BLAKE: Violin Sonata, Op. 586 (2007 Version of Op. 169): I. Allegro

Madeleine Mitchell, Howard Blake piano: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=75JUIJUQdek

Track 11: ALBAN BERG: Die Nachtigall (arr. M. Mitchell) from Violin Songs album Divine Art

Madeleine Mitchell, Andrew Ball piano: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KmpX0BkPCtQ

Track 12: OLIVIER MESSIAEN: Quartet for the End of Time:

VIII. Louange à l’Immortalité de Jésus

Madeleine Mitchell violin, Joanna MacGregor piano: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3pJ9qIZxIfQ

Track 13: BRIAN ELIAS: Fantasia [from In Sunlight: Pieces for Madeleine Mitchell NMC]

Madeleine Mitchell, Andrew Ball piano: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rbcNnw-A1yg

Track 14: JAMES MACMILLAN: Kiss On Wood

[from In Sunlight: Pieces for Madeleine Mitchell NMC]

Madeleine Mitchell, Andrew Ball piano: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9JzsTA5OKAE

Track 15: FRANZ SCHUBERT: Cello Quintet in C Major, D.956: 2. Adagio

Amadeus Quartet, leader Norbert Brainin with Robert Cohen, cello: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GvtvfolsClM

Track 16: BILL EVANS: Easy Living: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=T0ZwAJAgBFM

Track 17: BILL EVANS: Autumn Leaves: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=r-Z8KuwI7Gc

Track 18: BILL EVANS: When I Fall in Love: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=adPpG0Dnxeg

Track 19: MICHAEL NYMAN: On The Fiddle: I. Full Fathom Five

Madeleine Mitchell, Andrew Ball piano: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OoWywOdPYHY