The writer and journalist Penny Kiley was born in Kent, and studied English at Liverpool University, where she found herself at the epicentre of the city’s musical and cultural scene during punk, post-punk and beyond. In 1979 she became a regular contributor to Melody Maker and a little later on, Smash Hits. In the late 1980s, she became the music columnist for the Liverpool Echo, while also covering the Merseyside arts scene for other local publications.

Latterly, Penny continues to write about music, books and culture on her blog Older Than Elvis, and has now written a terrific memoir, Atypical Girl, about her life, career and belated diagnosis of autism. I was delighted that she agreed to come and discuss all of this with me on First Last Anything, and choose some favourite and significant records too. Our conversation took place on Zoom one evening in May 2023. We hope you enjoy it.

—-

JUSTIN LEWIS

So what records did you grow up with in your house before you started buying music yourself?

PENNY KILEY

It’s interesting, that one. When I was reading series 1 of First Last Anything, I felt there was some sort of dialogue going on between the different interviewees and between the interviews and the audience. And David Quantick [see FLA 6] was the one that said ‘old musicals’, and I guess I’m a similar age to him.

My dad was a Londoner, and he used to go to the theatre all the time in London because in those days normal people could afford to go. So we had Oklahoma! and Gigi and Carousel in the house. And I guess that gave me a grounding in really good songs. Over the years, that’s what I’ve always come back to, particularly now, when you get old and cranky and you don’t want to listen to the latest new sound: ‘I don’t care – I just want good songs, songs with stories.’

JUSTIN LEWIS

Musicals often seem to be about history or culture or identity, those elements.

PENNY KILEY

They have to be, because there’s a narrative anyway. But yes, I just like people putting thought into songs and not doing the obvious rhymes or references or allusions.

My parents weren’t hugely into music otherwise, but then schools were good. Everybody played the recorder when they got to a certain age, you know? And we had Singing Together (BBC Radio, 1939–2001), this schools radio programme.

JUSTIN LEWIS

Yes, I remember. We’d had Time and Tune (BBC Radio, 1951–) at infants school…

PENNY KILEY

I don’t remember that!

JUSTIN LEWIS

…but then at junior school, Singing Together. We’d all sit on the floor, cross-legged, in the school hall. There was a whole Archive on 4 documentary with Jarvis Cocker about Singing Together [broadcast November 2014, on BBC Sounds].

Did you play any instruments then at school, or were you in bands at all, anything like that?

PENNY KILEY

I played the recorder and then when I left junior school, I learned piano for about a year, but didn’t really get on with it. I did enjoy singing, though. I was in the school choir, in the back row, at grammar school, and we did Handel’s Messiah with the boys’ school down the road. That was a big kick. That was the first time I realised you can do a performance and get this huge adrenalin rush at the end of it.

—-

FIRST: T REX: ‘Jeepster’ (Fly Records, single, 1971)

JUSTIN LEWIS

It’s also Johnny Marr’s first single, or so he told Smash Hits back in the day. Was this the first you knew of Bolan?

PENNY KILEY

I must have heard ‘Get It On’ before then. I didn’t buy records very often, because I was thirteen, I didn’t get much pocket money.

JUSTIN LEWIS

To buy a record was a big deal, wasn’t it?

PENNY KILEY

Round about 1970, my parents bought a new stereo, so we had the opportunity to play records, and you’d see Cliff Richard or the New Seekers on the telly and that was a kind of entry-level stuff. But T Rex was the first thing that was mine.

Nobody else in the family got it apart from me.

JUSTIN LEWIS

Did you stay with their stuff for long?

PENNY KILEY

For a few years. After ‘Children of the Revolution’ [autumn 1972], I got a bit bored. The peak was quite short. I mean, my husband owns everything Marc Bolan ever made and 50% of it is actually unlistenable. Although he will dispute that.

JUSTIN LEWIS

Is this the earlier stuff, the long album titles, or the later stuff?

PENNY KILEY

The earlier stuff and the later stuff! The earlier stuff is just like just the hippy-dippy stuff. And then the later stuff is just frankly substandard because the quality control had gone out of the window. But the peak’s so good – enough to hang a legacy on.

JUSTIN LEWIS

And what is that peak? ‘Ride a White Swan’ [late 1970] to… ‘20th Century Boy’ [early 1973], I guess. Two and a bit years? And he becomes part of the light entertainment fabric, guesting on the Cilla Black Show [Cilla, BBC1, 27 January 1973], doing ‘Life’s a Gas’ on Saturday night television.

PENNY KILEY

‘Life’s a Gas’, the other side of ‘Jeepster’. That was like buying two singles. Of course, we always played B-sides in those days, but this was like having a double-A side because they were both so good. Both songs are on the Electric Warrior LP which I bought later – now seen as a classic. My first record has stood the test of time! I still play it, and I still hear new things in it all the time. Bolan had talent, obviously, but credit also to Tony Visconti, as producer, for bringing out the best in the songs.

I should also mention that, around this time, a lot of 50s and 60s stuff was getting reissued – the Shangri-Las, Phil Spector, doowop – and that fed into my musical education. There was also the rock’n’roll revival, another genre that’s stayed with me. The soundtrack LP to That’ll Be the Day (1973) was a big influence.

—-

JUSTIN LEWIS

Reading your memoir [Atypical Girl], my first surprise – given that I associate a lot of your work so much with Liverpool – is that you’re not from there at all. You’re actually from Kent.

PENNY KILEY

Yes, a place called Sittingbourne. Everybody knows the name because it’s on the railway. But there’s no reason to get off.

JUSTIN LEWIS

So what was it about the city of Liverpool that appealed to you? It’s worth saying that punk hadn’t happened at this point.

PENNY KILEY

I went there because of the university. I wanted to do English Language and Literature and not many universities did both. The English department had a good reputation and one of my teachers had a daughter who’d done English there a few years before me. I knew nothing about the North whatsoever. But it became like this whole new world. It was amazing because there was stuff happening all the time.

JUSTIN LEWIS

You say in the memoir how you’d prefer not to mention the music you were listening to before you got to Liverpool. Why do you think there’s this awkwardness about pre-punk? Was punk such a seismic event because of what happened next, did it follow a period where it was all rather dull – or were there things that you secretly still like?

PENNY KILEY

There was a real ‘Ground Zero’ attitude about punk. Everybody threw away lots of their records, or gave them away, or hid them in the back of cupboards, because they were embarrassed. We all had to pretend that we’d only ever liked certain things. I was listening to a mixture of stuff and some of it I would still listen to now, like The Who or Dylan. There was a lot of soft rock stuff that you just listened to because your friends had it. Quite pleasant, but it becomes dull after you’ve heard the Ramones.

JUSTIN LEWIS

When those Top of the Pops repeats started running on BBC4 [7 April 2011] with the episodes of April 1976, I remember thinking, ‘Okay, so it’s before punk rock, what’s going on?’ Even knowing the state of the charts at the time – lots of oldies and novelty records – doesn’t prepare you for quite how bad an episode is going to be. They had to fill 40 minutes at short notice. And it seemed to be the days before they’d invented onscreen captions, because anonymous bands would start playing with no lead-in from the presenter and you wouldn’t have a clue who they were. It’s a cliché, but ABBA turn up and it’s, ‘Oh, thank god – one we know.’ Even though you’d heard it a billion times.

PENNY KILEY

I still remember the early 70s Top of the Pops era as a ‘golden age’, mainly because of glam rock. But by the mid-70s it had got a bit dire. There was one shown again last week, from ’77, and I was thinking, This is so middle of the road. The entire programme, wall to wall.

JUSTIN LEWIS

Punk rock still hasn’t quite happened, unless you were reading the music press.

PENNY KILEY

The Sex Pistols were having hits, but it didn’t change that culture straight away. All that awful middle of the road stuff carried on for so long because punk didn’t really get mainstream. And at the time, I was probably watching Old Grey Whistle Test, with Bob Harris, more than Top of the Pops.

JUSTIN LEWIS

And Whistle Test didn’t really do punk, did it? You had to make an album to be on that.

PENNY KILEY

It was so serious about everything. And then you’d get something like Alex Harvey on [BBC2, 7 February 1975], and you’d go, ‘What the fuck is this?’

JUSTIN LEWIS

Oh, was that the ‘Next’ clip? I saw that quite a bit later. Terrifying!

PENNY KILEY

Yes, the Jacques Brel song. I was like 17, 18, and I didn’t really understand it at all. It felt way too grown up for me.

JUSTIN LEWIS

Once you know a bit more Alex Harvey, it kind of explains itself, but at the time… It’s so intense. When BBC4 started repeating Top of the Pops, I remember thinking, ‘Why not repeat some Whistle Test in full?’ But when you see one in full, it could often be terribly earnest.

PENNY KILEY

That anniversary programme they did a few years ago was all from the Bob Harris perspective! I got really cross because of Annie Nightingale being sidelined. Obviously, that’s a feminist issue, but also they made it sound like a really dull programme, even duller than it actually was.

JUSTIN LEWIS

I love Annie. People always talk about the Peel show being important for their musical education, but I didn’t really listen to Peel till I was at university. Throughout my teens, I listened to Annie every Sunday night, because even though it was, ostensibly, a request show after the Top 40 show, she would play increasingly left-field music as the evening went on.

PENNY KILEY

The first time I heard ‘Wuthering Heights’ was on her show, when it was a Sunday afternoon programme. A real ‘what is this?’ moment.

JUSTIN LEWIS

Tell me about getting to Liverpool, then, because your experience of music changes dramatically, within weeks.

PENNY KILEY

I arrived autumn ’76, and I went to all the gigs that were on – a huge mix of stuff. The most forward-looking one was Eddie and the Hot Rods at the Students Union [16 October 1976]. I loved that. They’re written out of the picture now, a bit, but I think they were an important link. I mean, that Live at the Marquee EP [recorded July 1976] is brilliant, even though they’re standing there on the cover with terrible flares. The actual music has so much energy.

But like you, I didn’t really know about John Peel, he was on past my bedtime when I’d been living at home. You’d read about stuff in the music papers, but you didn’t really hear it. I think there was one boy who lived upstairs in the halls of residence who had ‘Anarchy in the UK’ when that came out [November 1976] but he would play that alongside Jimi Hendrix and it didn’t really seem that different. I guess if you’d seen them live, it would have been an entirely different experience. They did play in Liverpool but hardly anybody went.

JUSTIN LEWIS

It was around this time that you met Pete Wylie.

PENNY KILEY

We were doing different courses – he was doing French, and I was doing English – but we both did classical literature in translation. That’s how I got to know him, we pretty much hit it off straight away. And Pete told me I should go to Eric’s, this was the beginning of ’77. It was a lot more than a punk club, although that’s what it got known for. The booking policy was pretty broad. It also had a lot of old rockabilly on the jukebox. It gave us all our musical education.

JUSTIN LEWIS

Could you see the potential even then, that Pete was going to be a musical giant? Was the charisma evident?

PENNY KILEY

There was definitely charisma. Somebody wrote an article about Liverpool in the Baltimore Sun [‘After the “Merseybeat”, 20 April 1979]. I don’t know why, or how we even saw it. But it mentioned Pete Wylie, and the picture was Pete Wylie walking down the street – and you know, ‘everybody knows him’. Liverpool was a village [in terms of the music scene at the time]. And he was one of the faces at Eric’s. The strapline on his website, even now, is ‘Part-time rock-star, full-time legend!’.

—-

JUSTIN LEWIS

How did you get into journalism, then? Had you always been interested in writing?

PENNY KILEY

I’d wanted to be a writer since I was five, but I was so obsessed with music, I just wanted to write about that. I knew how to write, and I was reading the music papers. I thought: I could do this. I sat on the idea for a bit, then in my final year, I started writing for the university mag. And then Melody Maker advertised for people, because the NME had some young writers and they thought they’d better get some too. So I became one of their young writers and I think Paolo Hewitt started around the same time as well.

JUSTIN LEWIS

Had there been particular journalists you always looked forward to reading, people you made a note of?

PENNY KILEY

There were people at the NME when I was a teenager in the 70s like Charles Shaar Murray, kind of stars in their own right. Obviously, Julie Burchill when she started. There were very few women doing it.

JUSTIN LEWIS

Jumping ahead a little bit, I think I had seen your name in Smash Hits, reviewing concerts – I always made a mental note of who was writing the pieces, not just who they were writing about – but I properly became aware of you when I switched to reading Melody Maker, around late 1985. And you did a piece on Half Man Half Biscuit, who maybe I had heard of but not quite heard. But it was a very funny piece, and so I thought: Oh, must hear some Half Man Half Biscuit, but also: must read more Penny Kiley.

PENNY KILEY

Oh, that’s good!

JUSTIN LEWIS

So when you joined the Maker, ’79, Richard Williams was still the editor? An amazing writer and editor, obviously. It goes through a lot of phases between then and when I properly started reading it.

PENNY KILEY

It was always ‘the poor relation’ compared to the NME, and obviously both were produced by the same company (IPC) – so it struggled, really, to find its own identity. When I started writing for it, one of its strengths was that it was very eclectic – it had a folk section and a jazz specialist, and there was (famously) the classified section at the back where musicians found people to be in their bands. It should have stayed with that and just moved everybody over a bit to make space for the new stuff.

JUSTIN LEWIS

I get the feeling you could be quite broad in what you could pitch. Presumably they wanted people outside London to give a flavour of what was going on?

PENNY KILEY

Yes, that’s why Richard hired me. I was in the right place at the right time, there was a lot going on in Liverpool that was worth covering. And when I started out, there were people who gave me the space to learn what I was doing: Richard Williams, and also Ian Birch who was the reviews editor before he moved to Smash Hits. I remember Allan Jones, who became the Maker’s editor, would give me pointers like, ‘You don’t write a 1,000-word review, that’s too long.’ But he would still give me the work. So I was learning my trade as I went along.

JUSTIN LEWIS

I switched to the Maker partly because by ’85, I felt a bit jaded with Smash Hits. I was fifteen, I’d been reading it for five years, and I was also interested by then in what was outside the Top 40. At the time, I figured I’d just slightly lost interest in the music, but when I revisited that patch of issues more recently, I realised, ‘Actually, for me, the writing isn’t as good as it had been either.’ It all got a bit wacky, everybody wanted to be Tom Hibbert. Fine if you’re Tom Hibbert, and there were still a few other great writers (Chris Heath, Sylvia Patterson and Miranda Sawyer a little while later), but if the whole magazine is trying to do that kind of joke, it gets a bit wearing.

PENNY KILEY

When it first started out, it was a lot straighter, but then it got a bit in-jokey and annoying.

JUSTIN LEWIS

Yeah. I got bored with all the brackets and exclamation marks. But you’re right, at the turn of the 80s, they’d have like an indie section, where there’d be a piece on Crass or the Young Marble Giants. And there was a disco page with a club chart.

PENNY KILEY

Yeah, they’d cover anybody.

JUSTIN LEWIS

And the rule seemed to be if it was a new band, they would get priority. Whereas an established act that predated the existence of Smash Hits would get a slightly sniffy reception. Like a perfectly alright Paul McCartney album. It was about ‘the new’. In fact, that period must be one of the few in pop history where just about everything of interest, certainly in the mainstream, was coming out of Britain. The US charts in that patch – turn of the 80s – were deathly. But the British charts were really varied.

PENNY KILEY

There was so much at the time that felt different. And I don’t listen to much new music now, but what comes my way doesn’t feel different.

JUSTIN LEWIS

I’ve been trying to work out, for a while now, about why the charts were so important to me when I was 10, 11, 12 – and some of that is undoubtedly that I’m a bit of a stat nerd. But it was also that sense of variety. You’d have a Saxon record next to a Soft Cell record in the top 40 and Tony Blackburn would play both of them, right next to each other. And of course loads of great records weren’t charting at all, but that chart show was like an education, every week: ‘There’s some stuff you’re not going to like, but it’s a wide range.’ There was this incredible sense of democracy about it all.

But what was it like for you to revisit your journalism from that period? Was writing Atypical Girl the first time in a while you’d read it again?

PENNY KILEY

I still had all the cuttings books in the cupboard, but I hadn’t really done anything with them. I started looking at stuff when I was writing the book and then I looked at them again when I started my Substack of archive cuttings.

JUSTIN LEWIS

Reading some of the pieces again, they’re quite prescient. There’s that review of OMD when they’re well known in Liverpool but haven’t yet broken through nationally.

PENNY KILEY

I think I said, ‘They’re going to be big.’ You just knew.

JUSTIN LEWIS

Are you reviewing the room, though, as well as the performance? You’re spotting what’s happening.

PENNY KILEY

Yeah, there’s all that: OMD, The Teardrop Explodes, the Bunnymen, out of the Eric’s lot. They were all on the verge of breaking through – it was just obvious. They did so many gigs, and the gigs got bigger and bigger and there was more of a buzz about them. And inside, you become aware of that.

And I was doing some interviews… I was really lucky, actually, getting The Cramps as my first interview [June 1979]. I mean it sounds nuts, because of that image they had, but actually they were so easy.

JUSTIN LEWIS

It’s often the way, isn’t it? It belies the image, the idea that the outlandish people might be the most difficult.

PENNY KILEY

First of all, they are actually quite nice people. But secondly, they had things they wanted to say. So, basically, you press the buttons and off they go, it’s fine, but you are so dependent on people wanting to do it, and play the game. If they don’t do that, you’re a bit screwed.

I see some old interviews on the TV and I look at the bands lined up on one side of the table and the interviewer on the other side and the band’s giving them a really hard time and I think, I know what you’re doing there ‘cause I’ve been there. You know: ‘We’re the gang and we’re not comfortable with this situation, so we’re going to just become this tight unit and take the piss out of anybody that wants anything from us.’ Once that dynamic is set up, it’s hard to break.

But I was so shy that I hated interviews. So I’m looking back at my cuttings now for Substack and realise, Oh, there’s not really that many interviews. That’s a shame. But they did scare me.

JUSTIN LEWIS

So you did… ten years at the Maker?

PENNY KILEY

It petered out in the mid 90s, but there wasn’t any kind of big finish.

JUSTIN LEWIS

By which time you were working on the Liverpool Echo and the Daily Post, writing about music and arts as well.

PENNY KILEY

The Echo was one of the biggest regional papers in the country then. It turned out to be a bit of a dead end, career-wise, but it felt like the job had my name on, so I went for it. I was freelance, but the contract was to write two columns a week. It changed a lot over time – I won’t say it ‘evolved’ because it wasn’t really me making the changes, but whoever was in charge of the paper at the time. So, I was reviewing records and whichever big name was coming to the Empire Theatre – but quite a lot of grassroots music stuff, which I was most interested in pushing, and was how I developed a name for myself. I had a lot of run-ins with various people at the Echo who didn’t think I should be doing that sort of thing because I was writing about people their children hadn’t heard of.

JUSTIN LEWIS

Which is surely the whole point, though! To introduce readers to new people!

PENNY KILEY

Yes, it’s not about whether you’re famous or not, it’s about supporting what’s going on in your city. So there was a bit of a mismatch of vision for quite a long time. Liverpool was just an amazing place for the arts. It’s kind of embarrassing because I’m living in the shires now, and when I tell people who aren’t from Liverpool how good it is, you can see them thinking, ‘That doesn’t compute.’ They’ve got their image of Liverpool.

JUSTIN LEWIS

It’s fascinating in your book to see these names of people on the rise, not just the people in music, but names like Jimmy McGovern and Alan Bleasdale having plays on at the Everyman.

PENNY KILEY

We had LOTS of theatres! The Everyman, the Playhouse, the Empire, the Neptune, and the Unity. And little odd venues on top of those.

JUSTIN LEWIS

And having this new serial, Brookside (1982–2001) on the new Channel 4.

PENNY KILEY

And going back to music, Radio Merseyside, the BBC local station, in the 80s, was a really big part of the music scene’s infrastructure. Janice Long, obviously, and there was a guy called Roger Hill who did the longest running alternative music programme on UK radio – 45 years – and it’s just been axed in the latest BBC cuts.

JUSTIN LEWIS

Obviously, we’re having this conversation just as the BBC is chipping away at its local radio output, seemingly to almost nothing, and one thing that’s undervalued about local radio is discovering new talent. All those stations, commercial and BBC, were uncovering new bands, because there’s more to local radio than phone-ins. Shows like On the Wire on Radio Lancashire. Every station had one of those, but increasingly no longer.

PENNY KILEY

When I see Top of the Pops, or From the Vaults on Sky Arts, I spot so many Liverpool acts. They just keep coming, and when I was writing for the Echo, it was taken for granted that there’d be a handful of Liverpool acts in the charts at any given time.

—-

JUSTIN LEWIS

Atypical Girl is also partly the story of your autism diagnosis. How long ago were you diagnosed?

PENNY KILEY

Five years ago now.

JUSTIN LEWIS

I’m in the early stages of investigating all this myself at the moment, and it really makes you re-examine your life. Has your diagnosis made you review your life in journalism in a different light? Had you already started writing the memoir before it, and did that change your method in writing it?

PENNY KILEY

I can’t remember when I started thinking about writing it. It’s been years. At first, it was going to be ‘woman in a man’s world’, the usual thing. It was a midlife crisis book for a while, because I’ve been doing this blog, Older Than Elvis, about coming to terms with being middle-aged.

So I was writing it in stops and starts because of circumstances, and then I went on an Arvon writing course with Laura Barton, one of my favourite music writers, as one of the tutors. (She did the brilliant ‘Hail, Hail, Rock’n’Roll’ column in The Guardian.) I saved up all my pocket money for it, specifically because it was Laura doing it. (The other tutor was Alexander Masters and he was great, too.) It was hugely expensive, but great fun, and during that week I realised that my book was actually about reinvention. This was still a couple of years before I got the autism diagnosis. One of the things about autism, as you probably know, is about masking and not knowing, not having a solid sense of identity, and of who you are, and trying on different identities.

JUSTIN LEWIS

Because you’re trying to emulate other people, or the behaviour of other people, at least.

PENNY KILEY

Partly, you’re trying to fit in; partly, it’s just trying on things for size and seeing what works. And that’s why there are chapters in the book called things like ‘how to be this’, and ‘how to be that’. Because that’s the story of my life. And then alongside the personal stuff, there’s the whole thing about regeneration, the way Liverpool’s changed. So it might not be obvious, but the overall theme is reinvention.

When I started pitching it, I wondered if there was enough music in it, or too much music. And it suddenly dawned on me that it’s an autism memoir disguised as a music business book.

JUSTIN LEWIS

The title – it’s a Slits reference, isn’t it? ‘Typical Girls’.

PENNY KILEY

It is. But ‘Atypical Girl’ is still a working title. We’ll see what happens.

JUSTIN LEWIS

Reading it, I was thinking about how books on music written by women have always ‘had’ to be about more than the music. I was thinking about Sylvia Patterson’s book a few years back, I’m With the Band, and she mentioned in an interview that she just wanted it to be a book about being a journalist, and she was persuaded to write about her background and her mother.

PENNY KILEY

I saw a talk that she gave where she said exactly that thing. And her book ended up as a mixture of the personal and the professional and it won an award, so it does work.

When I first started reading music journalism memoirs, they were all by men. It all seemed to be ‘rifling through cuttings books’, and it was always people with a really middle-class background, so there was a lot of ‘Oh I’m so self-deprecating…’

JUSTIN LEWIS

Yes, they can afford to be. ‘How did I get here?’

PENNY KILEY

‘Oh, I just fell into it.’ Yeah yeah.

JUSTIN LEWIS

I liked how unapologetic you are about applying to Melody Maker. That it was a calculated approach.

PENNY KILEY

I didn’t fall into it, no. I wanted to do it. There haven’t been many times in my life where I’ve known what I’ve wanted, but that was one of them.

JUSTIN LEWIS

There’s also a section about what is punk and what isn’t punk. Blogging is punk, Facebook isn’t. Television isn’t punk, radio is.

PENNY KILEY

That list was on my blog. I stole the idea from Frank Cottrell-Boyce.

JUSTIN LEWIS

It’s still so relevant now, even more so perhaps. People used to say that punk was about being yourself, but in those days, it wasn’t quite as simple as that. We live in an age now where actually, it’s much more possible to be yourself than it used to be. Because – sorry to rub this in – but I was too young for punk. In that I don’t really remember the records. I remember new wave, the Boomtown Rats and Blondie, that wave, but my perception of punk itself was ‘blokes with Mohican haircuts and safety pins’, so not about originality.

PENNY KILEY

No, I hate all that.

JUSTIN LEWIS

And hopefully, at a time when there are millions of podcasts, First Last Anything has a punk edge to it.

PENNY KILEY

It’s DIY.

JUSTIN LEWIS

It’s DIY! Thank you. How long have you been doing the Older Than Elvis blog, then?

PENNY KILEY

I started to blog on the night before my 50th birthday because I promised myself I would do it before I was 50, and I always meet deadlines. So that’s 15 years now.

—-

LAST: MARGO CILKER: Pohorylle (2021, Margo Cilker/Loose Music)

Extract: ‘That River’

JUSTIN LEWIS

I just checked pronunciation and her surname is apparently pronounced ‘Silker’.

PENNY KILEY

I particularly don’t know how you pronounce the name of the LP.

JUSTIN LEWIS

It may be a reference to the birth surname of the war photographer Gerda Taro (1910–37). I’ll pretend I didn’t just Google that. I really liked this record. This seems to be somewhere between country and western, or roots and Americana anyway. Have you liked this kind of music for a long time?

PENNY KILEY

Yeah, a long time. I don’t really listen to much new music, but I picked up on this because Allan Jones, who used to be my editor at Melody Maker, is now a Facebook friend, and he goes to gigs all the time. And he posted that he’d been to see her in London. He said, ‘She’s a bit like Lucinda Williams’, and I thought, ‘Well, I really like Lucinda Williams’, so I gave it a listen, and thought, ‘I might buy this. I like it.’

ANYTHING: HANK WILLIAMS: ‘I’ll Never Get Out of This World Alive’ (1952, single, MGM Records)

PENNY KILEY

I chose this because, like discovering T Rex, it was another pivotal moment: in this case, when I stopped listening to music for work, and started listening to what I chose. Also, I think you have to have lived a bit to ‘get’ country music. I’m reading Lucinda Williams’ memoir at the moment (Don’t Tell Anybody the Secrets I Told You); she made her breakthrough LP in her mid-thirties (Lucinda Williams, 1988) – and I discovered it a bit later (she’s older than me) in my mid-thirties. Also, when I discovered it, alt-country was big at the time, and someone described that as what punks listen to when they get old.

I got into country in a big way when I was going through a divorce in the 1990s. Which is a bit of a cliché. Somebody asked me how I was coping after we separated and I said, ‘A bottle of Jack Daniels and the Hank Williams box set.’ And that was actually the truth. We were talking at the start of this about writing songs, and Hank Williams… he’s such a great songwriter. And the sound is really interesting because it’s on the cusp, it’s hillbilly, but music is about to morph into rockabilly and rock’n’roll and all the rest of it. So he is a bit of a missing link as well, but what a brilliant writer. I just love his writing.

JUSTIN LEWIS

And this one in particular, ‘I’ll Never Get Out of This World Alive’, it’s a funny song in its own way.

PENNY KILEY

Yeah, it’s really funny and clever. I chose it because he’s known for sad songs but there’s another side to him.

JUSTIN LEWIS

But it’s overshadowed by the fact that it’s almost the last thing he recorded.

PENNY KILEY

And it was a posthumous hit. I mean, with a title like that, it just all falls into place, doesn’t it?

JUSTIN LEWIS

I think country music, country and western was almost the last music I got to of the main genres because my dad had a reasonably sizeable but very eclectic record collection, but it lacked country and western – we might have had a Dolly Parton compilation, I think, but that was about it. And obviously with some country music, there is this connection with the Republican Party. Not always the case, of course.

PENNY KILEY

Yeah, going back to Lucinda Williams’ memoir, she’s starts off with: we’re not all racist in the South, you know.

JUSTIN LEWIS

See also the Chicks, as they’re now called. And a number of others.

PENNY KILEY

You say ‘country and western’ and I always cringe a bit at that term. I would always say ‘country’.

JUSTIN LEWIS

Funnily enough, I was reading an interview with Margo Cilker, who’s from Oregon, I think, and she describes her music as ‘West’.

PENNY KILEY

That’s fair enough. Every track’s different on this album – the word ‘different’ keeps coming up. But they’re all her, and they’re all ‘West’ – in a way.

—-

JUSTIN LEWIS

I know that we share a frustration with music documentaries with all the same talking heads on them.

PENNY KILEY

The same men. Because women aren’t supposed to know about music, according to the BBC. I can’t watch that stuff anymore, although Women Who Rock on Sky Arts was an amazing series, because all the talking heads were women. The musicians themselves, a few commentators, music writers, journalists – all women. It was just so refreshing. It was made by women with a woman director, and – okay – it was a bit of a statement, it would be nice if we were just integrated. We’re still not. And every time I write to the BBC about it, they give me stupid replies. They don’t understand the concepts of representation or marginalisation.

JUSTIN LEWIS

One of your notable interviewees in the first few years of your career was the Marine Girls in 1982, featuring Tracey Thorn.

PENNY KILEY

Everything But the Girl had done one single, ‘Night and Day’ (1982). Tracey had met Ben at Hull University, they’d done the single together, and the Marine Girls were about to split up (which I didn’t pick up on at the time). I enjoyed doing that piece. I got this massive spread in the Melody Maker and Janette Beckman took these amazing photographs so it worked out really well.

JUSTIN LEWIS

Didn’t it get the front cover?

PENNY KILEY

I’ve only had two front covers and that was the second one. First one was The Cramps!

JUSTIN LEWIS

In your book, you mention a quote of Tracey’s about the 1980s, and how all the things that are now supposed to sum up the 80s – Royal Wedding, Live Aid, yuppies, Duran Duran – weren’t really relevant to our lives. And I found this interesting – obviously I became a teenager in the 80s, and remember all those things. But the 80s are important to me because they were slightly weird. I wasn’t going out that much – almost no bands came to Swansea and if they did, they’d play an over-18s venue. So I relied on television and the music press and radio, so got close to a lot of this stuff. But the nostalgia of the 80s removes the offbeat and the underground. It just becomes this triumphalist thing about MTV videos. Being that little bit older, and you were going out a lot more, did the 80s feel like a bit of an anti-climax after the late 70s?

PENNY KILEY

Everything in my entire life has been an anti-climax since then! That makes me sound like a real saddo, and actually I did still get excited about my new favourite bands, like Orange Juice or James. But the thing about the 80s and the way people talk about it, the way it’s portrayed… It’s very dependent on where you were living at the time. So, people who were in London, part of the big financial boom and everything, were having a lovely time, and they cared about Princess Diana’s frock. And those of us who were trapped on the scrapheap by Thatcherism were living in an entirely different country. I have never forgiven the Conservatives for that, and I never will.

JUSTIN LEWIS

Well, we’re still seeing the effects of it, aren’t we?

PENNY KILEY

The legacy is still there indeed. I don’t want to talk about politics but growing up in Liverpool in the 80s did politicise me, because how could it not? Nobody had any money, but we made our own fun. It was an incredibly bohemian culture. There were people doing music, theatre, or film, or visual art, and a lot of the time, the same people were doing all that stuff. You could sign on and not get hassled too much. And with the Enterprise Allowance Scheme you could actually get money for being in a band. So Liverpool was a very exciting place to be, and I’d much rather have been there than somewhere where everyone was just running around with loads of money.

—-

Penny Kiley’s memoir, Atypical Girl, will be published by Birlinn on 5 February 2026. Further details here: https://birlinn.co.uk/product/atypical-girl/

She continues to blog at olderthanelvis.blogspot.com

Her Substack, a growing archive of her press work and interviews, can be found at pennykiley.substack.com

You can also find Penny at various other places via this link: https://linktr.ee/pennykiley

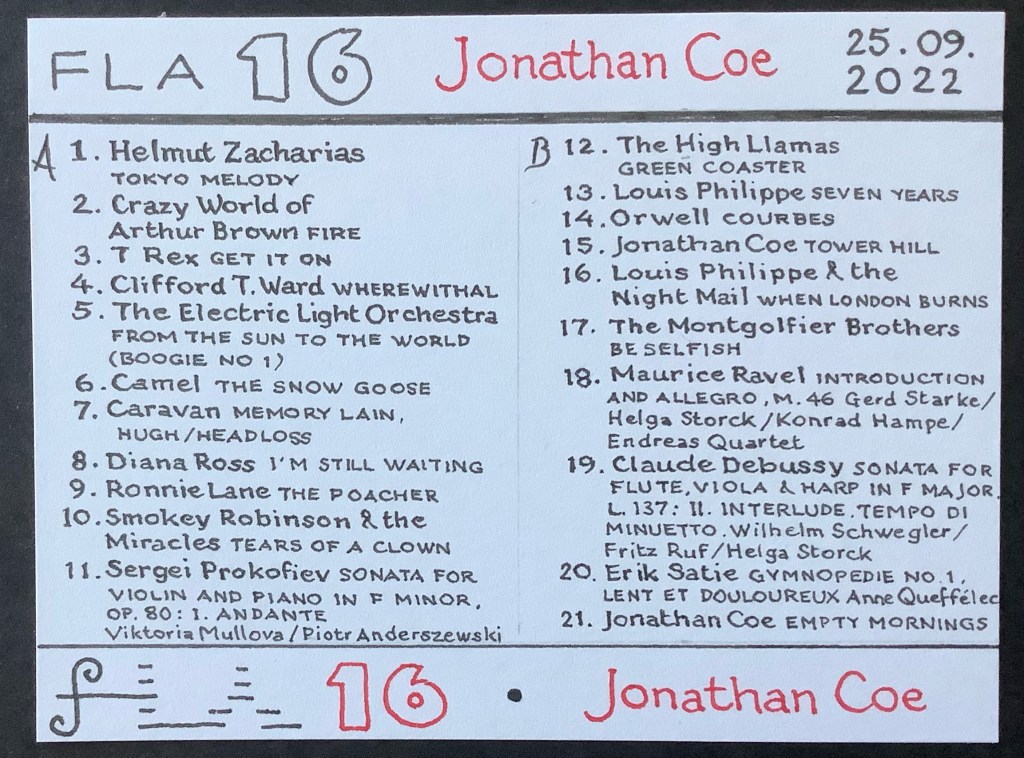

FLA PLAYLIST 18

Penny Kiley

(For the time being, this site and project uses Spotify for the conversation playlists, but obviously I disapprove that Spotify doesn’t pay artists and composers properly, and other streaming platforms are available, as are sites to buy downloads and buy recordings. For consistency, you can also listen to the selections via YouTube (where available), and links are provided in each case, below.)

Track 1: RICHARD RODGERS AND OSCAR HAMMERSTEIN II: Oklahoma!:

‘The Farmer and the Cowman’

Gordon Macrae, Gloria Grahame etc: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tUJLVUTJSF0

Track 2: T REX: ‘Jeepster’: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=U8kGuZMHycU

Track 3: T REX: ‘Life’s a Gas’: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=G4z8Wi-5uwY

Track 4: THE SHANGRI-LA’S: ‘Give Him a Great Big Kiss’: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0KLJaoAGXTY

Track 5: FRANKIE LYMON & THE TEENAGERS: ‘Why Do Fools Fall in Love’

[from That’ll Be the Day soundtrack]: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DXJ6mo7aeUw

Track 6: MOTT THE HOOPLE: ‘The Golden Age of Rock’n’Roll’: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XEM3T7kT4JI

Track 7: EDDIE AND THE HOT RODS: ‘Gloria (Live at the Marquee)’: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=iNI39woKbxY

Track 8: OMD: ‘Electricity’: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XXNF4KoVyoU

Track 9: THE TEARDROP EXPLODES: ‘Read It in Books’: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Bd3OM4mWSCw

Track 10: ECHO AND THE BUNNYMEN: ‘Pictures on My Wall’: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=f2DSO7gYD3Y

Track 11: PETE WYLIE: ‘Hey! Mona Lisa’: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=62-Bs3cHBbw

Track 12: THE CRAMPS: ‘Human Fly’: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WK5Xe1SK0r8

Track 13: ROBERT GORDON AND LINK WRAY: ‘Red Hot’: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tNm0IzwKcqs

Track 14: THE MARINE GIRLS: ‘Honey’: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=aPk4sUH6Uf0

Track 15: ORANGE JUICE: ‘Falling and Laughing’ (Postcard Version): https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=13Gdj_jOQEc

Track 16: JAMES: ‘Johnny Yen’: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8qAg6sI36Rs

Track 17: WACO BROTHERS: ‘Bad Times Are Coming Round Again’: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2iMOelbLm2M

Track 18: LUCINDA WILLIAMS: ‘Passionate Kisses’: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dEqXV9hGk-I

Track 19: MARGO CILKER: ‘That River’: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8Wp1CEExUxo

Track 20: HANK WILLIAMS: ‘I’ll Never Get Out of This World Alive’: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=19vApPwWqh8

Track 21: ELVIS PRESLEY: ‘Blue Moon’: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MiY5auB3OWg