Born in London, the composer and educator Bernard Hughes studied Music at St Catherine’s College, Oxford during the 1990s, where he also was in the Oxford Revue with amongst others, a young Ben Willbond. After graduating, Bernard studied composition at Goldsmiths College and was awarded his PhD by the University of London in 2009. As well as his work as a composer, he is Composer-in-Residence at St Paul’s Girls’ School in London.

Although Bernard is probably now most renowned for his work in choral music – I particularly have enjoyed the Precious Things collection released by Dauphin in 2022, with the Epiphoni Consort – much of his canon of piano works has been recorded and newly issued by the soloist Matthew Mills, on a CD called Bagatelles.

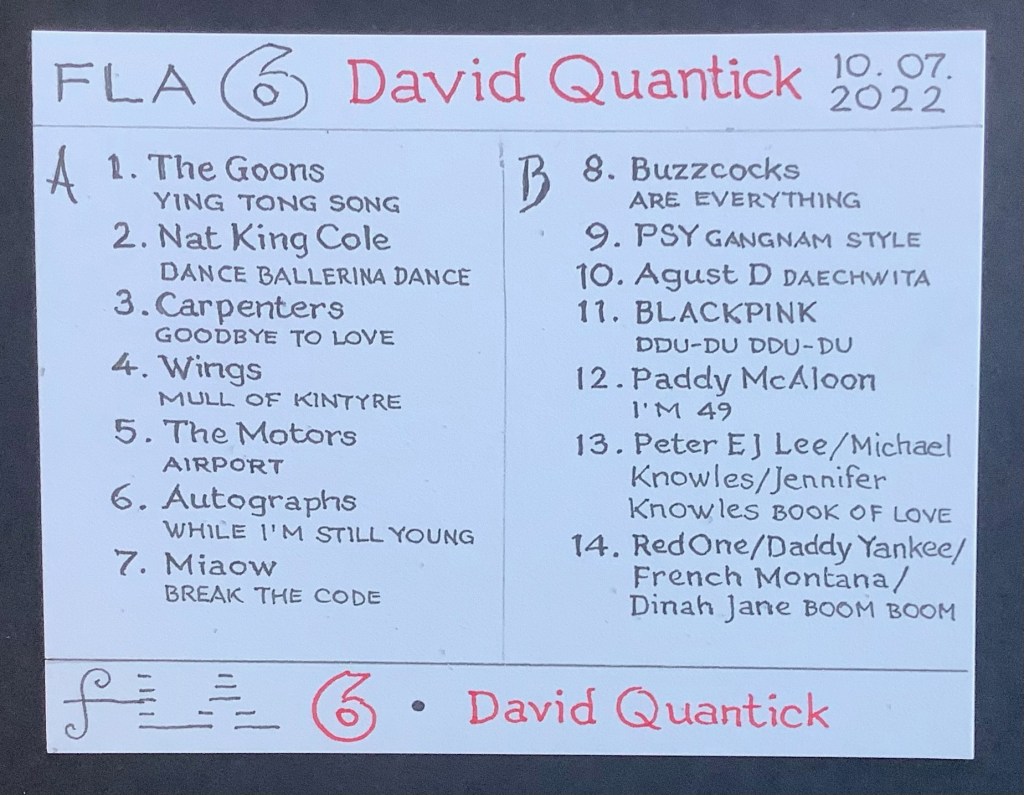

To coincide with the release of Bagatelles, Bernard and I had an exhilarating and fascinating conversation one morning in April 2023 to discuss that, his long association with the BBC Singers, his formative years in London and Berlin, and some of his favourite recordings, as well as his first, last and anything selections. We hope you enjoy this first instalment of First Last Anything’s second series.

BERNARD HUGHES

When I was a child, my dad conducted the choir at the Catholic Church at the end of our road. So I would be in the organ loft a lot, hearing him conducting and singing various pieces, a couple of which in particular, as an adult, I can think: Yes, my judgement as a five-year-old was spot on. They were Mozart’s ‘Ave verum corpus’, a very late a cappella piece [1791, the year of Mozart’s death], and a brilliant anthem by Henry Purcell, ‘Rejoice in the Lord, alway’ [c. 1683–85].

My dad had trained as a singer, and had been offered a contract with what became the English National Opera. He didn’t pursue the singing career, but he had a very, very fine voice, and as he conducted, he would sing the bass line of the hymn. I think that’s been very influential on my understanding of harmony – hearing the whole thing but particularly him coming through on the bass line.

JUSTIN LEWIS

I remember my own father doing that. He had a record with that Purcell anthem on it, by the way. He loved lots of different types of music, but he liked church music very much and he used to harmonise a bass part underneath a piece of music quite often.

BERNARD HUGHES

I think that’s a useful music skill – see what the bassline is going to do, that’s always been a thing I can hear. My son is extraordinary, he has perfect pitch, and he can just play chords because he’s hearing those pitches. Whereas I’m working out the bassline in abstract terms from the degrees of the scale, of the qualities, as opposed to specifically D flat, you know. Having perfect pitch is a two-edged sword. It’s not an unalloyed blessing in that sense. It makes me work a bit harder, because I don’t listen and think, That’s an F.

—

BERNARD HUGHES

I’m absolutely not a religious person, but it’s worth mentioning something about church music at that time. In the 1960s, the Second Vatican Council had opened up and got rid of the Latin mass and the mass in the local language, and this applied to music as well: there was a vacancy, if you like, in the 1970s for new Catholic and liturgical music in English. So there was a new generation of composers around – in fact, there was someone writing this stuff who my dad had worked with in that choir.

I didn’t know that a lot of what I was hearing was quite new. I’ve pieced it together retrospectively. The harmonies are kind of modal, and there are elements of dissonance. So the Catholic Church is not the most progressive organisation, but if it was progressive in any sense, it was in its approach to music in the 70s and 80s.

JUSTIN LEWIS

That’s really interesting, piecing it together later, and connecting these things. Back in the day, I was trying to work out where I belonged in listening to classical music. I was in a state comprehensive, and we were lucky to have a music department, we had quite a good school orchestra, which I was in, but nothing quite felt fully connected up or explained. Also, mine was the last but one year of O level before they changed to GCSE. It’s really weird it modernised slightly for the GCSE because it was under a Conservative government.

BERNARD HUGHES

They brought in this three-part of Listen Perform Compose.

JUSTIN LEWIS

Right. There was no composing when I did O level.

BERNARD HUGHES

Exactly. I was the first year of GCSE (1988), and obviously that suited me down to the ground in terms of writing music. But a generation of music teachers had got well established in their careers without ever teaching composition – and suddenly it was one-third of the GCSE course. Subsequently, when I did A level music, it was an option, you could do it as an option – and then from 2000 it became compulsory. So again, A level students who would previously have got A level without doing a note of composing, found it a compulsory part of the course.

JUSTIN LEWIS

It makes me smile when people are a few years younger and did GCSE rather than O level: they’ll say, ‘Oh well, of course we studied The Works by Queen’, whereas for us, there was no pop; there was barely acknowledgement that jazz existed.

BERNARD HUGHES

When I was teaching GCSE Music around 2008, they introduced a Britpop option for teaching as a history topic. And I was having to explain – in 2008! – the Labour government of 1997, because by 2008 the people’s perception of Tony Blair, for example, was very different.

JUSTIN LEWIS

I always felt when I was at school, the teachers were good but there didn’t seem to be so much explanation of context and history, why some of these pieces came to be, what caused them.

BERNARD HUGHES

My degree was quite history-based, and my teaching now has that dimension: ‘What was happening in the wider world at this time?’ These things didn’t happen in a vacuum. And as a school music teacher, you can’t shrug off pop music – and in fact I’ve picked up a lot of things over the years from my students. One lent me a cassette of the second Ben Folds Five album, Whatever and Ever Amen. I looked at the cover and thought, Oh god it’s a boy band, this is gonna be really awkward. But obviously I fell in love with it within the first two bars [of ‘One Angry Dwarf and 200 Solemn Faces’], it’s got these brilliant openings. And Ben Folds has gone on to be one of my absolute favourites.

JUSTIN LEWIS

I find it so interesting he was a drummer originally.

BERNARD HUGHES

Yeah, he had that autobiography out during lockdown [A Dream About Lightning Bugs]. A very interesting character, extraordinary musician and pianist. But I came to him through a recommendation from a student. I like to keep an open mind. That’s how you find things.

—

BERNARD HUGHES

I got started on piano lessons when I was about five or six. This really cranky old machine, which the convent round the corner were getting rid of, but it got me started. And then, when I was about seven, there were these blank manuscript sheets which I would start writing on, without anyone suggesting to me that I should. Quite odd, because they were four-line staves rather than five – they were used for chants. So I would add in a fifth line with a ruler, and start writing music. I would write a key signature where I did a mixture of sharps and flats within the key signature. And my dad would say, ‘You’re not allowed to do that!’ Although I found out later that somebody like Bartók would write an F sharp next to an E flat. So I was writing music with not much idea of how it sounded, before knowing what a composer was, or that I should be a composer.

When I was about eight or nine, we had a cassette player in the car for the first time. We got four cassettes from WHSmiths, which went round and round for the next ten years:

Buddy Holly’s Greatest Hits, an album called Elvis Sings Leiber and Stoller, a Louis Armstrong tape, and this cassette of Revolver by The Beatles… in an unusual order.

JUSTIN LEWIS

Yeah, they often rejigged the track listings for the cassettes, so that side one and two had roughly equal running times.

BERNARD HUGHES

For me, to this day, Revolver should begin with ‘Good Day Sunshine’, as opposed to ‘Taxman’, because that was the first song on that cassette copy. Although it still finished with ‘Tomorrow Never Knows’.

[NB: Compare the cassette running order of Revolver, with its LP original:

CASSETTE LP

Side One: Side One:

Good Day Sunshine Taxman

And Your Bird Can Sing Eleanor Rigby

Doctor Robert I’m Only Sleeping

I Want to Tell You Love You To

Taxman Here, There and Everywhere

I’m Only Sleeping Yellow Submarine

Yellow Submarine She Said She Said

Side Two: Side Two:

Eleanor Rigby Good Day Sunshine

Here, There and Everywhere And Your Bird Can Sing

For No One For No One

Got to Get You Into My Life Doctor Robert

Love You To I Want to Tell You

She Said She Said Got to Get You Into My Life

Tomorrow Never Knows Tomorrow Never Knows

—-

FIRST: LONDON PHILHARMONIC ORCHESTRA: Favourites of the London Philharmonic (Music for Pleasure, 1980)

Excerpt: Litolff: ‘Concerto Symphonique No 4 in D minor: II. Scherzo’

BERNARD HUGHES

My aunty Celia, my mum’s sister, gave me this compilation cassette and I found it again when my parents cleared out their house. I just played this over and over again, found it very inspiring. It’s hard to tell now whether I love them because they’re ingrained on me – many of them stand up as really great pieces.

JUSTIN LEWIS

Long deleted, I think, but I found it on Discogs. The photograph is not a very good reproduction of the cover and inlay but I managed to squint at the liner notes, and it seems it was compiled based on melodic strength. And all 19th century – I think the Weber is the earliest, about 1820.

BERNARD HUGHES

Yes, clearly it’s a collection of lollipops: here’s some fun things to get you into music.

JUSTIN LEWIS

Compilations can be very helpful, especially when you’re just starting to get into something.

BERNARD HUGHES

And if you said to the compiler to this, ‘There’s a child out there who’s gonna hear this compilation and it’s gonna change their life…’, they’d be delighted. I had trouble tracking down some tracks for years.

But the one in particular that grabbed me then was by this guy called Henry Charles Litolff (1818–91), who’s completely obscure now. It’s called ‘Concerto symphonique: Scherzo’. It had been huge in the 1940s – it’s about five minutes long, so I think it fitted well on to records in the early days of the very short 78rpm records. On this compilation it’s played by Peter Katin (1930–2015). I think the radio used to play it when it was ‘Well, we’re slightly early for the news’, you know. For whatever reason, it’s not even one piece, but just one movement of one piece. And it never gets played as a piece anymore – if I’d known it had been programmed for a concert in the UK in the last 30 years, I’d have dropped everything to be there.

I absolutely love it, it’s full of energy, it’s fun, and one bit suddenly goes very simple: Ding. Ding. Ding. I remember thinking at that young age, ‘I could play that bit’, but recently I found a YouTube film where it scrolls through the sheet music and even ‘the easy bit’ is phenomenally hard. But it made me specifically think: I want to grow up and be able to play that piece. And I have never got anywhere remotely close to it.

—

FIRST (Part II): PRINCE AND THE REVOLUTION: Purple Rain (Warner Bros, 1984)

Excerpt: ‘Let’s Go Crazy’

JUSTIN LEWIS

Fast forward a few years, and you first hear this. Purple Rain. Tell me about this.

BERNARD HUGHES

This would have been ’85 or so. We were living in what was then West Germany [of which more, later]. My friend Patrick got the tape of it first. And I had no concept of it at the time, because we still had Elvis and Buddy Holly in the car, so I had no idea if it was old or just a collection like my London Philharmonic cassette. But we listened to this album over and over in his parents’ house.

JUSTIN LEWIS

In the UK, it felt – with ‘When Doves Cry’ – that he became famous very suddenly. ‘1999’ had made the charts before that, but not particularly high (#25, early 1983), and then with Purple Rain, he became very famous. Whereas in America, he’d done it more incrementally – it was his sixth album, and each one had made him that bit more prominent. It felt weird that there was a film behind it, that felt massive, although admittedly it’s not a great film. Apart from the performances… there’s that really long version of ‘Let’s Go Crazy’ (on the 12” single) which they edited down for the LP.

BERNARD HUGHES

They had to go back and re-record a lot of that live footage, because it wasn’t quite right when they recorded it. And bits of it are from the day they launched it, when they went to the club.

JUSTIN LEWIS

Yes, the last three songs on the album: ‘I Would Die 4 U’, ‘Baby I’m a Star’ and ‘Purple Rain’ itself. Before I ever saw the film, I thought, ‘Why is there applause at the end of “Baby I’m a Star”?’ And of course it was because they recorded those three songs live on the same day.

BERNARD HUGHES

It does have an incredible energy. When the deluxe release of it came out, with most of the stuff they had cut, I think they had been right to. Except for the 10-minute version of ‘Computer Blue’ which is brilliant – the version on the original LP is horribly edited, there’s a real clunky jumpcut. But of course that editorial sense was what he lost later, in the 90s… that sense of quality control – when he just released everything that came into his head. Although lately, through a friend who lent me the CD, I have come round to Chaos and Disorder.

JUSTIN LEWIS

Oh yes, the last contractual obligation for Warners (1996), so it was seen as a ‘cupboard’s nearly bare’ record.

BERNARD HUGHES

I’d always written it off as that, but he’s got together with his pals and they just absolutely jam. It’s brilliant.

But going back to Purple Rain, and listening to that over and over again… When I went away to university, I knew far less music than any of my students do now, or than my son does now. I knew a small amount, but I knew it really, really well. And I’m not sure now whether people listen so heavily to something: you listen to something, then it’s ‘Let’s move on to something else, what’s next?’

—

JUSTIN LEWIS

So how did you develop your composing into a career?

BERNARD HUGHES

I was just always writing. When I was about 15, the teacher at school got me to write the incidental music for a school production of A Midsummer Night’s Dream. And I had a composition teacher, but I didn’t really meet any other composers my age. I didn’t know much about contemporary music. At university, I didn’t really take it very seriously, I got a third in the composition paper in my finals because I was doing comedy stuff with the Oxford Revue.

But when I did a Masters in London and started taking it more seriously. If at any stage I’d stopped, nobody would particularly [have noticed]. You know, lots of people write music and then don’t anymore. I think I just never stopped.

JUSTIN LEWIS

It’s interesting you’re most associated, or at least I associate you, with choral music. But it wasn’t what you were composing early on, is that right?

BERNARD HUGHES

Having said that my dad was a singer, I was very sniffy about people singing. I never sang in a choir myself, or wanted to sing, and so I had no interest in the big choral scene around the chapel choirs of Oxford. But then, very late, I accidentally got into it. In about 2002, my late twenties, I wrote and sent in a piece for a BBC Singers workshop. That led to a commission from them, which led to another workshop and so on.

JUSTIN LEWIS

What was that first commission for them?

BERNARD HUGHES

There was this big contemporary music festival, the Huddersfield Festival in 2003, and I wrote this very ambitious piece based on 150 aphorisms. I spent ages researching and getting permission for these aphorisms, everything from Francois de La Rochefoucauld right up to Spike Milligan and Jeanette Winterson. This massive 15-minute tapestry only ever had one performance, but the next workshop with the BBC Singers led to the idea of a piece called ‘The Death of Balder’. It was this Norse myth from a book of translations which I inherited from my godfather.

I proposed this piece as five to seven minutes but it became clear it was more like 25 minutes. This big choral piece, and in fact, it’s had quite a lot of outings, considering new pieces often get done once and never again. But this one did, and it ended up as the backbone of the first of my albums, I Am the Song.

This was 2006, 2007 – and from there I became a choral composer. Once I started doing it, I realised I loved doing this, working with choirs and the sounds they make. It was something I could do. I could sometimes feel with an instrumental piece that I didn’t know where to start or what to write, but I’ve never really been stuck on a choral piece.

JUSTIN LEWIS

What’s your starting point, then, with a choral piece?

BERNARD HUGHES

I often go for a little walk before I start, just hear them in the abstract. I get away from the keyboard as quickly as I can and on to the computer. Writing for a choir, you don’t want to be too influenced by what you happen to be able to play on a piano. When you’re singing, you can have one low note down there, and one high note up there. You don’t have to be able to play it.

Also, I collect texts… I’ll skim books of poetry, looking for texts. One thing I do with text, almost a kind of trademark, is I use a lot of changeable time signatures which will often go with the rhythm of the words – and often the rhythm of words is uneven. On my Precious Things album of choral music (2022), there’s a piece called ‘Psalm 56’, which goes, ‘My enemies will daily swallow me up’ – that’s an example of letting the text actually drive the rhythm, rather than imposing an artificial rhythm on it. Or on the BBC album, ‘The Winter It is Past’, which is a Robert Burns poem. It is strictly metric, but I put it into 5/4, which can sound quite jagged and uneven, but when you’re dealing with text, you wouldn’t say that sounds odd or out of kilter.

JUSTIN LEWIS

The BBC Singers have been much in the news this year. Do you think everyone understands the full extent of why these cuts made by the BBC on their Singers and also their Orchestras need to be taken seriously?

BERNARD HUGHES

When the news came out, I thought, This is terrible news for me in my niche – but will it have cut through to people who aren’t in this world? And it has done – all this amazing work the Singers have been doing for years is now being publicised. They’ve not been doing anything different [since March], but now they’re out there tweeting about it, they’re getting some coverage.

There’s a 50/50 gender split in their commissions. I don’t know this for sure, but over the past three years, I think the BBC Singers, as a group, has performed more music by women composers than any other group in the world. They do a concert every Friday, and 50% of every concert will be by women composers. But then they’ve been doing that anyway; they’ve just not had the recognition for it.

So some of it made a splash and it needed to. It was partly people like me saying ‘The BBC Singers need to be saved’, because that’s my world, devastating for people within it. And it was partly people saying, ‘If we don’t put our foot down or do something now, one thing after another will go, like the orchestras, until there’s nothing left.’

I started out in a workshop with the BBC Singers, which led to commissions, having a full album by them in 2016, then in 2020 there was a portrait concert that was 75% my music, and that culminating in a Proms commission in 2021. I am a shining example of that process working well, and closing the BBC Singers means that no-one else follows that path.

And even for people who aren’t looking to follow that path: they do workshops with undergraduates where they sing undergraduates’ music and workshop it. And if you’re an undergraduate who’s got no plans to go on and become a composer, you’ve had your piece sung by the BBC Singers, you’ve got a record of that piece – that’s incredible, and the idea that would be taken away from future generations is awful. So while I know a lot of the Singers personally, I’m friendly with them, in a broader context, culturally, this is something that the BBC should be shouting about proudly, and not [hiding it] shamefully.

JUSTIN LEWIS

While it’s not just the BBC’s responsibility to keep something like this alive, I do think one of the roles of the BBC is to do what nobody else would do.

BERNARD HUGHES

Exactly, yeah.

JUSTIN LEWIS

And they have less money than they used to, and we know why that is!

BERNARD HUGHES

That is full stop the fault of Nadine Dorries, who froze the licence fee, when they put the World Service on to the licence fee, when it used to be paid by the Foreign Office, when they made all the licence fees for the over-75s free… All of those things. Those are all governmental decisions that the BBC have had to deal with.

JUSTIN LEWIS

Radio still tries but I find television has basically given up on the arts in general, and I’m really struck by how you mostly only really get music coverage on television now when it’s a competition, when there’s a competitive element.

BERNARD HUGHES

There’s a British classical music writer, Andrew Mellor, who now lives in Denmark. And when the BBC Singers story appeared, he wrote a piece for Classical Music, in which he said that in Denmark, there’s an equivalent of the BBC Singers, the Danish Radio Vocal Ensemble. They have a slot, every weekday, three minutes before the six o’clock news, [called Song for the Day] where they’ll sing something, like a traditional Danish folk song, recorded and filmed. So everybody in Denmark is aware of their existence and of what they do and what they sound like. Whereas here, recently, lots of cultured and educated people have said to me, ‘I didn’t really know who the BBC Singers were or what they did.’

At the moment, the jury’s out on the ultimate decision, but I owe my career as a choral composer, that I am one at all, to the BBC Singers, to their current producer Jonathan Manners, and the producer who originally took a punt on me, Michael Emery, and who gave The Death of Balder a chance. So I’m really exercised about this, and really want it to be resolved, not just for me, but for the wider ecosystem.

JUSTIN LEWIS

So it’s not just a question of money.

BERNARD HUGHES

No, it’s not, it’s a lack of awareness of what they do – if they got rid of them, no-one would really notice. The BBC head of music who made the decision comes from a pop background – not in itself a problem, but they have zero understanding of what the singers do, presumably sees them as a bunch of old fuddy-duddies in suits singing old music, whereas they do a phenomenal range of stuff, from the very old to the contemporary. But I think on their part, it was ignorance of a) what the singers do, and b) what the singers mean to people.

JUSTIN LEWIS

Absolutely. My question was more a general one about cuts, in that it seems to me music coverage is now events-led. So they’ll do the Proms, they’ll do Glastonbury, and very well, but there’s barely any regular music series on television now. Later’s about the only thing left, and that isn’t year-round. Certainly very little serious music.

BERNARD HUGHES

Although, like you say, there is a stronger argument for there being classical programming than pop music because other people aren’t putting out classical concerts and that’s what they should be doing.

—-

ANYTHING: ANNA MEREDITH: Varmints (Moshi Moshi, 2016)

Extract: ‘Nautilus’

BERNARD HUGHES

I had been aware of Anna Meredith, a very successful Scottish classical composer, who had written a piece for First Night of the Proms. And then about five or six years ago now, she suddenly brought out this hybrid of dance, electronic, classical and rock music.

JUSTIN LEWIS

It really does defy categorisation.

BERNARD HUGHES

Absolutely. My son and I have this category of music we call ‘love at first sight music’. Things that, within a few bars, you just know. There’s a few other things like that: the first Scissor Sisters album, Ben Folds, and also my other great enthusiasm, The Divine Comedy, which I loved within five bars. And it’s true of this too: Anna Meredith’s Varmints. I thought: ‘This is where it’s at.’

JUSTIN LEWIS

So was this the opening track, ‘Nautilus’? I think I either first heard it on Radio 3 or 6Music, because both stations made a point of championing it.

BERNARD HUGHES

It was ‘Nautilus’, yeah. She’d actually introduced that piece about two years before, although I hadn’t heard it then, but it was an incredible statement of intent. You think you know what the pulse is – and then halfway through, the drums kick in.

JUSTIN LEWIS

Oh yes!

BERNARD HUGHES

And it’s a completely different pulse. Astonishing and it answers a question I’d always had which is: ‘Could a classical musician do pop?’ You get certain crossovers the other way, but this shows her classical thinking: ‘What kind of polyrhythm can I pull out of this?’ And yet it still sounds like dance music. It’s got an extraordinary opening.

JUSTIN LEWIS

I saw Frank Skinner live a couple of years ago and he came on to that intro.

BERNARD HUGHES

There’s a phenomenon in pop music where intros have got shorter. They cut to the vocals quicker, and now it’s not 25 seconds, or 20, it’s now 5 seconds. And ‘Nautilus’ starts with the same chord for about a minute before anything else happens, it’s like: ‘This is my territory, and if you don’t like it, go away, because this is what it is.’ It’s an amazing courageous statement of intent which I just love.

On the same album, ‘The Vapours’, which I love [JL agreement], and which partly inspired a piece I wrote for my school orchestra concert band called ‘Gooseberry Fool’ which we released as a charity single. We meant it to have the same joyous kind of energy.

I took my son to a live concert, with orchestra, of Varmints, and it was one of those nights, which you don’t often get from classical music, where we walked out really buzzing from it. And her next album, Fibs (2019), again has some beautiful, wonderful, extraordinary songs on it. So in terms of not getting stuck in my ways, there’s something. Sometimes I hear people and I think, ‘That’s great, but that’s the kind of thing I could do.’ I couldn’t do Anna Meredith’s stuff – I love it, and I couldn’t do it.

JUSTIN LEWIS

I really need to see her live.

BERNARD HUGHES

I was lucky to be at the launch concert of Fibs. The band are phenomenally tight, because there are all these time signature changes and counterrhythms and polyrhythms. It’s virtuoso stuff. She plays the clarinet and bashes her drum… and there’s one brilliant bit, in ‘The Vapours’ where it’s in 7/4, so she bangs her drum and she’s on the beat, and then when it goes to the next bar, she’s suddenly off the beat. So she’s just doing a semi-beat, but it becomes the off-beat and then it gets back on the beat. It’s a mind-blowing trick.

LAST: BJARTE EIKE / BAROKKSOLISTENE: The Alehouse Sessions (Rubicon Classics, 2017)

Extract: ‘I Drew My Ship’

JUSTIN LEWIS

And while we’re on the subject of defying categorisation, that could be said about another of your selections – The Alehouse Sessions.

BERNARD HUGHES

I’ve never been a fan of what you might call folk music. The younger me might have turned my nose up at this, but I heard this first during one of those lovely Radio 3 mixtapes they play from 7 to 7.30 before their evening concerts. So I went and looked this up afterwards, and it was this Purcell overture – not actually the track I’ve specified, but I got the whole album. It’s not only a brilliant fresh way of looking at music, mixing folk songs with more classical material, like Henry Purcell, but it’s also a nod to the fact that Purcell would have been in the ‘proper’ theatre, and had his posh performance, and then would have gone to the bar and played his popular stuff.

I find ‘I Drew My Ship’ just unbelievably moving. First of all, it’s so bare. Maybe it’s a young man thing to throw everything, bells and whistles, at a piece of music, but as I get older… [I love] the sheer simplicity of that beginning, with just those harmonics on the strings and then about four-fifths of the way through the playing stops and there are all these singers who are not trained singers, they’re just the instrumentalists who happen to be singing. It’s that untrained dimension that’s so captivated, so touching.

JUSTIN LEWIS

It’s very striking and with the vocals, there’s this interesting way of using the voices that are off-mic sometimes.

BERNARD HUGHES

I haven’t seen them live yet, but they apparently perform it like a kind of happening or jam session. They wander around, singing from whenever they are. I believe they don’t particularly plan what they’re going to do in what order. It’s just very freestyle. And Bjarte, the violinist leader of the group, is brilliant.

I did an arrangement of this, actually, for my choir at school, which we’re doing at the moment. It works really well for unaccompanied voices – very different from that recording.

As a musician, studying and working in music for 35 years, and still having an enthusiasm for it, I can still get home from my job teaching music, and find exciting new music that I like. [I never want to lose that feeling. ‘I Drew My Ship’ can reduce me to tears, quite, quite easily – and I’m not someone who weeps very often.

—-

BERNARD HUGHES

As I mentioned, when we were talking about Prince, when I went to university I knew very little, but I knew it very well, and my enthusiasm got me through that process as much as knowing anything! At my interview, the interviewer who went on to be my tutor said, ‘Tell me about a piece you’ve found recently that you really love.’ And I must have gone off on one about The Rite of Spring (premiered 1913). But I’d struggle to choose between that and another Stravinsky piece in my desert island discs: I first heard Symphony of Psalms (1930) when I was about eighteen, around Christmas time, this James O’Donnell performance at Westminster Cathedral.

JUSTIN LEWIS

Symphony of Psalms is perhaps the lesser-known piece.

BERNARD HUGHES

They’re very different, [hard to believe] they’re by the same composer. It seems quite unlikely, but it’s an astonishingly powerful piece. And since then, Stravinsky has been my absolute guiding star, in musical terms, I must have read every book about him, from Stephen Walsh’s to Richard Taruskin’s. If I did a specialist subject on Mastermind, it would be Stravinsky – although he’s a bad one to choose because he lived to be about ninety and lots happened to him.

JUSTIN LEWIS

As I was listening to Symphony of Psalms, I was thinking, Something about this sounds particularly unusual, and I suddenly realised there are instruments not present. There’s no upper strings, for instance – no violins, no violas. There’s no clarinet.

BERNARD HUGHES

And it has two pianos – and two harps! And the pianos particularly give that ‘Dunk! Dunk!’ sound at the very beginning – which Leonard Bernstein described as ‘two gunshots’.

Who starts a religious piece with two gunshots?! Yes, it’s a unique sound, lots of flutes and oboes, and then this choir coming in… Stravinsky really could make a piece sound his own. There’s another Bernstein quote: ‘When you’re listening to a Stravinsky piece: “YES, this is the best Stravinsky piece.” And then you listen to another Stravinsky piece and you think: “YES, this is the best.”’ Whichever piece you’re listening to by him, that’s the best one.

JUSTIN LEWIS

Symphony of Psalms has made me think of the connection with Prince’s ‘When Doves Cry’.

BERNARD HUGHES

Which is what?

JUSTIN LEWIS

There’s no bass part on ‘When Doves Cry’.

BERNARD HUGHES

Of course. The upside-down version!

—

BERNARD HUGHES

When I’m reviewing, for the Arts Desk, I like to go to smaller or lower profile events – often with younger musicians, or things that just don’t get covered in mainstream coverage. Especially since lockdown. I’m by no means a straightforward cheerleader, but I do go in with a view to not slagging people off. I will be honest, but I’ve chosen which things I’m gonna go to, so they’re things I’m expecting to enjoy.

The reason for this is I’d been going to concerts which were just washing over me. So when I have to give an opinion, I sit there in a different way. Not just about the music, but how the concert is being presented.

Last week, I saw this screening, with a live orchestra, at the Barbican of this Alexander Korda sci-fi film Things to Come (1936), with a score by Arthur Bliss. It had been the first fully orchestral score for a film, the first soundtrack album, and the first film the London Symphony Orchestra did, who went on to a huge tradition of soundtracks, things like Star Wars. So, with Things to Come, I was thinking: Am I at a film screening which happens to have a live orchestra, or am I at an orchestral concert which happens to have a screen? At times, they had to project the dialogue as subtitles on to the screen, because the music was too loud – because obviously in a film, you can’t turn down the [volume on the] orchestra. And there’s a limit to how low you can turn down an orchestra.

So I’ve found it’s really increased my enjoyment of going to things, with a friend, either a musical or general friend because you can bounce ideas off them. ‘What did you think?’, you know.

—

JUSTIN LEWIS

Your new album is not one of choral music, but of piano music: Bagatelles.

BERNARD HUGHES

Matthew Mills, a long-time friend and colleague, and a wonderful pianist, had offered to record my complete piano music. It’s nearly the complete piano music – I realised I left one thing off the list I sent to him, and then in the recording sessions, we decided to ditch one item because it was just too much.

But it’s a real range of pieces, some really virtuosic, some very avant-garde and quite dramatic, and then some very simple melodic pieces: a couple of pieces I wrote for my children before they were born, when they were in utero, and I played them to them when they were little. There’s one piece that’s a sequence of pieces from beginner to Grade 5 in the course of eleven pieces. I like writing complex music, but I like writing simple music. I don’t have a style.

There’s also a new suite of pieces where I’ve reworked some old pieces – I’m always interested in repackaging, transforming, rewriting old pieces of music, often in quite inappropriate ways. So, the final movement of JS Bach’s St Matthew Passion (1727) – this great statement of religious faith, this shattering last movement at the end of three hours of music, and I’ve turned it into a little cheeky kind of piano tango. That new piece, the Partita Contrafacta, is entirely made-up of reimaginings of old pieces of music, by Baroque composers. As with Precious Things, it’s varied. That’s my watchword. I don’t want to be doing the same thing over and over again.

JUSTIN LEWIS

And do you strive for that variety when composing for your secondary school pupils too?

BERNARD HUGHES

Yes, I always do. I know them, I know what they can do, and so I can place their strengths. If there’s a particularly strong singer who can do a solo…

JUSTIN LEWIS

And you can learn from them as well.

BERNARD HUGHES

Absolutely. There’s nothing quite like that feedback. Sometimes you can write something you think will be really obvious in terms of what you want from it, and then the players play it, and you realise that you’ve not communicated accurately what you want, it’s your fault. The players aren’t being difficult.

It’s difficult to predict what people are going to find hard, but as you get older, you get better at knowing the pitfalls, particularly in choral writing. There are some things that are hard to do, and then there are some things that sound impressive, but actually aren’t that hard to do. I really like writing for the school, I’ve been there eight years, and just about every single ensemble in the school has had something by me during that time. It’s a real privilege.

—

JUSTIN LEWIS

As we mentioned earlier, you spent some of your childhood in Berlin.

BERNARD HUGHES

The family moved over in 1983, me and my two sisters, for three years, so when I was between nine and twelve. It was in the middle of the Cold War.

JUSTIN LEWIS

Of course! The Wall was still there.

BERNARD HUGHES

Absolutely, a very heavily militarised city, big military presence. I went to the British military school there. My big regret is I didn’t really learn German, although in the last five years, I’ve been properly learning it as a hobby.

JUSTIN LEWIS

Are you using Duolingo?

BERNARD HUGHES

I am, and I have an online teacher as well. My Duolingo streak is 1169 days [by the time this piece was edited: 1216!]. I’m grateful that I have a perspective on my time in Germany. You can read all you want about the Wall, but I was there, I saw it. You could look up and see a watchtower with an East German guard, carrying a gun, looking around. Even as I describe it, I can’t capture what that was like. We’d do school trips to East Berlin, and see the greyness and bleakness of it, buildings with bullet holes in them. It was a very formative few years, and I could have stayed another year, but me and my big sister were approaching secondary school age, and my parents wanted to come back and get us into schools in the UK.

JUSTIN LEWIS

You went to some quite noteworthy concerts in that period.

BERNARD HUGHES

Yes, Herbert von Karajan (1908–89) was still conducting the Berlin Philharmonic, and my parents would have regular tickets. My dad took me on several occasions. And I had no real concept at the time that Karajan was quite as famous as he was, but he was a very old man by then. He would be helped to the podium and he sat down when he conducted, and would barely move. He was just about keeping going, just by force of will. But he had a charisma, even at that age.

This would have been ’86-ish… What would I have seen? I can remember hearing the Mendelssohn Violin Concerto, Daniel Barenboim playing Beethoven… admittedly, I equally remember hearing a Shostakovich symphony and absolutely hating it. But the really memorable one was Mozart’s 21st Piano Concerto (1785), with Walter Klien (1928–91) as the soloist. And in those days, at the Berlin Philharmonie, on your way out you could buy the cassette and the score of what had been played in the concert.

I was absolutely seized by this piece, and I’m sure my dad must have noticed. So on the way out, he brought me the score of it and the cassette of Walter Klien playing it. Number 21 is known as ‘Elvira Madigan’, because the second, slow movement was in the film of the same name (1967).

With that cassette, I worked out something and no one told me to do this. I had a double cassette player. I played one of the parts in, recorded it on to the cassette, played that cassette out loud, and bounced it across to the other cassette player, while playing the next part in. I built this score up, bouncing it backwards and forwards between the two cassettes, adding a line at a time on the score – and then, when I had the full orchestral backing, I could play the solo piano part over the top. I’m kind of impressed, looking back, that I worked out how to do that all for myself.

JUSTIN LEWIS

That’s really ingenious.

BERNARD HUGHES

I also used to record myself improvising, on to cassette, these long 15-minute improvisations. Sadly, those are lost – although maybe they were terrible!

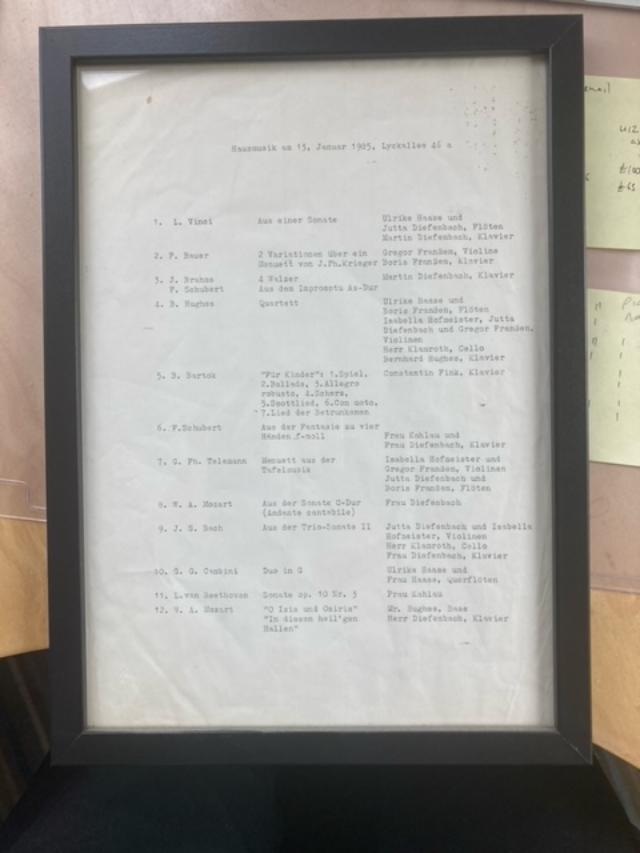

But the other thing about Berlin: my mum was in this local circle of parents and they put on a concert of their kids playing music in this judge’s front room. I wrote a piece for that, for piano. I’ve still got the programme. It’s 13 January 1985 [see below].

JUSTIN LEWIS

How fantastic!

BERNARD HUGHES

But I had a big panic on the day. It was around the time that ‘Together in Electric Dreams’ came out, and my piece had the same chord pattern with the descending arpeggio. Now, none of these people would ever have heard of this song, my parents wouldn’t have known, so they weren’t going to point any fingers. And it’s a very standard chord progression, I now know. But I remember having a genuine panic, thinking, God, people are going to think I’ve stolen this tune, and I’ll be publicly unmasked.

For more information on Bernard, see his website at www.bernardhughes.net

You can follow him on Bluesky at @bernardhughes.bsky.social and on Instagram at https://www.instagram.com/bernardlhughes/

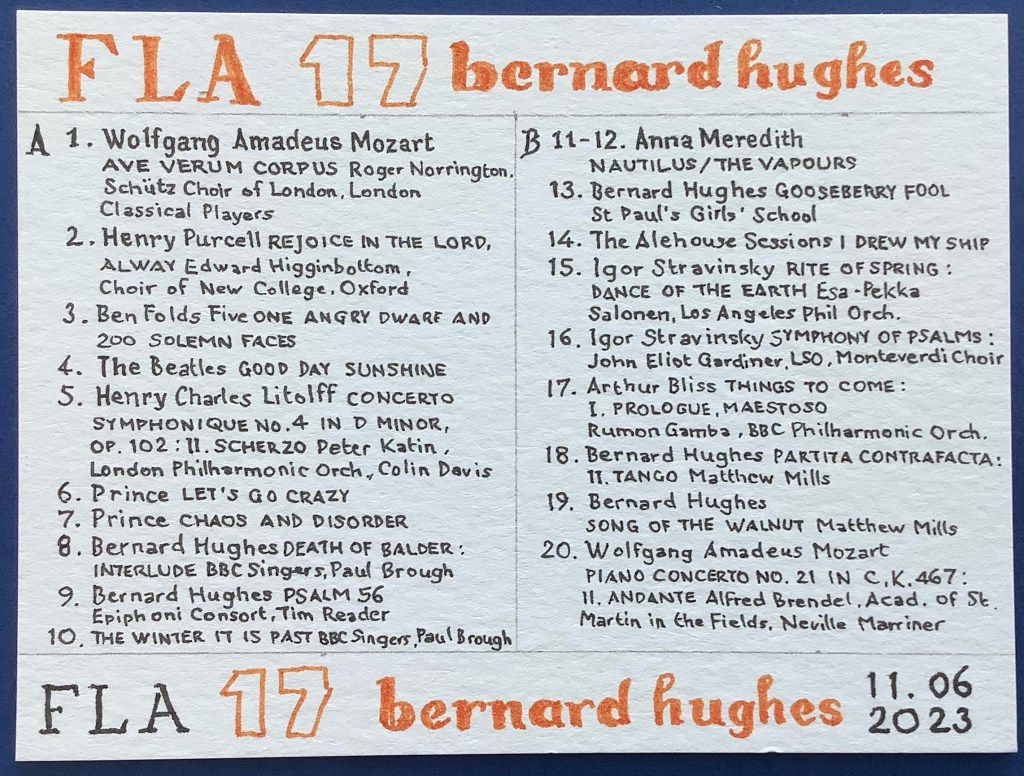

FLA PLAYLIST 17

Bernard Hughes

(For the time being, this site and project uses Spotify for the conversation playlists, but obviously I disapprove that Spotify doesn’t pay artists and composers properly, and other streaming platforms are available, as are sites to buy downloads and buy recordings. For consistency, you can also listen to the selections via YouTube (where available), and links are provided in each case, below.)

Track 1: WOLFGANG AMADEUS MOZART: ‘Ave verum corpus’, K. 618

Roger Norrington, Schütz Choir of London, London Classical Players: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hW4px6avEwg&list=PLcZMzs1nkFiv6fFQJEqSa6NUM5QUcm53b&index=20

Track 2: HENRY PURCELL: ‘Rejoice in the Lord Alway’

Edward Higginbottom, Choir of New College, Oxford: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_a27JP_6yI4

Track 3: BEN FOLDS FIVE: ‘One Angry Dwarf and 200 Solemn Faces’: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GwFBshjGe8I

Track 4: THE BEATLES: ‘Good Day Sunshine’: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=R9ncBUcInTM

Track 5: HENRY CHARLES LITOLFF: ‘Concerto Symphonique No. 4 in D minor, Op. 102: II. Scherzo’

Peter Katin, London Philharmonic Orchestra, Colin Davis: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FxBX3pu1D4g

[NB The Katin recording on the original album dates from 1970, and was conducted by John Pritchard, but that recording is currently neither on Spotify nor easily traceable on the web. Bernard would also recommend the recording by Peter Donohoe and the Bournemouth Symphony Orchestra, conducted by Andrew Litton, released in 1997, and available on the Hyperion label, cat. no. CDA 66889. You can find it here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JAPucIV6Pa4]

Track 6: PRINCE AND THE REVOLUTION: ‘Let’s Go Crazy’: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WGtCC7bUkIw

Track 7: PRINCE: ‘Chaos and Disorder’: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6bQmVk4Otw8

Track 8: BERNARD HUGHES: ‘The Death of Balder: Interlude’

BBC Singers, Paul Brough: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1gmIKXrQG34

Track 9: BERNARD HUGHES: ‘Psalm 56’

The Epiphoni Consort, Tim Reader: [Currently not on YouTube]

Track 10: BERNARD HUGHES: ‘The Winter It Is Past’

BBC Singers, Paul Brough: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xqETmNZaa9w

Track 11: ANNA MEREDITH: ‘Nautilus’: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=b7Ak8PBlO4I

Track 12: ANNA MEREDITH: ‘The Vapours’: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bdjHrahr2XY

Track 13: BERNARD HUGHES: ‘Gooseberry Fool’

St Paul’s Girls’ School: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sZ3RJKFtfYk

Track 14: TRAD/BJARTE ELKE/BAROKKSOLISTENE/THOMAS GUTHRIE:

The Alehouse Sessions: ‘I Drew My Ship’: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4S_hHg0CFfY

Track 15: IGOR STRAVINSKY: ‘The Rite of Spring: Part I, The Adoration of the Earth – Dance of the Earth’

Esa-Pekka Salonen, Los Angeles Philharmonic Orchestra: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=iB4Jd42vyLM

Track 16: IGOR STRAVINSKY: ‘Symphony of Psalms: Exaudi orationem meam’

John Eliot Gardiner, London Symphony Orchestra, Monteverdi Choir: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_PgtW3IS2AU

[Bernard also recommends the James O’Donnell recording with the Westminster Cathedral Choir and City of London Sinfonia. Again, it is on the Hyperion label, released in 1991, with the cat. no. CDA 66437. You can find that here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0BeRtgg0br0]

Track 17: ARTHUR BLISS: ‘Things to Come: I. Prologue, Maestoso’

Rumon Gamba, BBC Philharmonic Orchestra: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HWrHdUhCZmI

Track 18: BERNARD HUGHES: ‘Partita Contrafacta: II. Tango – instead of an Allemande (after JS Bach)’

Matthew Mills: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gjbia46Qwps

Track 19: BERNARD HUGHES: ‘Song of the Walnut’

Matthew Mills: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Bx9gm00otwQ

Track 20: WOLFGANG AMADEUS MOZART: Piano Concerto No. 21 in C., K. 467: II. Andante

Alfred Brendel, Academy of St Martin in the Fields, Sir Neville Marriner: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TLyD9oHbz7E

[In our chat, Bernard mentioned Walter Klien’s interpretation, a recording of which can be found on YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=EKOFyabRbfc]