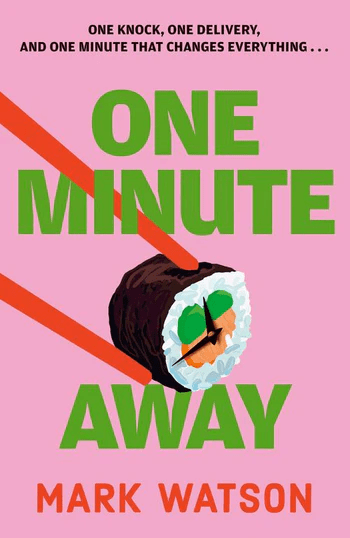

For over twenty years now, the writer-performer Mark Watson has sustained two parallel careers. In one of them, he has pursued stand-up comedy to great acclaim, both in live settings and via broadcast vehicles like BBC Radio 4’s Mark Watson Makes the World Substantially Better, BBC4’s We Need Answers and Mark Watson Talks a Bit About Life, a third series of which premiered on Radio 4 in 2025. Simultaneously, he has written a total of eight novels (including 2020’s Contacts, and 2025’s One Minute Away), plus a non-fiction book, a graphic novel, and a memoir published in 2023 called Mortification.

Mark was kind enough a while back to tell me how much he had enjoyed reading various instalments of First Last Anything, and so – as I am an admirer of his work – it seemed logical to ask if he’d be interested in taking part himself. To my delight, he agreed. We spoke over Zoom for 90 minutes or so, one day in late October 2025, and I was particularly interested to find out how his enthusiasm for music helped to shape and inform his own attitudes to performing and writing. We hope you enjoy our chat.

—–

JUSTIN LEWIS:

So what records did you have in your house growing up before you started buying your own, before you started making your own choices?

MARK WATSON:

My mum didn’t particularly listen to music around the house, but my dad was quite a serious music fan, a serious pop music fan, at least – he wasn’t what you’d now call a muso. We’d watch Top of the Pops, we’d listen to the charts on a Sunday, that top 40 countdown with Bruno Brookes was quite a big ritual. And my dad would buy records – singles and LPs – fairly often. There are certain things that it’s pointless being nostalgic about, but the download era has unfortunately made the charts a meaningless exercise really. The idea of the nation holding its breath to see what’s come in at number one feels like a thing we won’t get again. I used to enjoy the suspense of that.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

The charts are for the music industry only now, I think.

MARK WATSON:

When I was very young, we lived in Canada for a year. In Alberta, in the middle of nowhere.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

Oh! I went there when I was about eleven, for about a month – our base was Calgary.

MARK WATSON:

We flew into Calgary, I believe. I’m too young to remember most of this, I was four, but my earliest childhood memories are from that period. My dad was a teacher and he did a job swap with a teacher over there, so slightly rashly, he took his young family to the rural wilds. And in that period, his brother, my uncle, used to tape the charts from the radio and send them on cassettes.

My dad also used to have, you probably had them yourself, the Guinness Hit Singles books.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

I very much did!

MARK WATSON:

If I saw an act on Top of the Pops, I was the sort of kid who would flick through that book to see a rundown of their hits. Nonetheless, I was still limited to what my dad had in his collection, which was extensive, but if you were that 10-year-old now, you could literally listen to any song in the world. There are many reasons to lament the way the digital age has impacted the way we buy music, but it’s also true that it’s a wonderland: everything that’s ever been recorded is pretty much freely available for anyone to explore.

I remember when someone showed me Napster, in my early twenties. I simply couldn’t believe it. I remember just typing all sorts of different songs in to test it, it just didn’t seem possible. Just as when Amazon launched, rather than a sort of sinister mega corporation, for a while it seemed like this magic machine where you could put in any book you’d ever read in your life, and it would just send it to you. An innocent age.

When I was thinking of the First, Last and Anything categories for this, it dawned on me that technically, the first record I bought was ‘Dancing in the Dark’ by Bruce Springsteen, because while we were in Canada, my dad took me to a record shop and I have an early memory of him lifting me up so I could hand the money over and buy this. And seeing the lyrics on the back of the sleeve.

So I could have gone for that, but it’s stretching a point to say that was my record purchase, really.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

So, instead, let’s talk about this…

—-

FIRST: THE CRANBERRIES: Everybody Else is Doing It, So Why Can’t We? (Island Records, 1993)

Extract: ‘Linger’

JUSTIN LEWIS:

I was working at HMV in Cardiff when this went really big in early 1994. Because it came out for a while in this country, before any of the tracks had been hit singles. Then they had a massive hit in America with ‘Linger’ and they deleted the album in the UK, you could only get it as a US import, which we were playing in the store every day, even then. And then once ‘Linger’ finally became a hit here, they reissued the album. So I heard this a lot at the time. But I don’t think I’d heard this in full since about 1995.

MARK WATSON:

Well – I revisited it yesterday because of this chat, and again, it was a long time since I listened to any of it apart from the famous songs. This was my first album purchase, and it was on cassette. It’s sort of arbitrary that it was the first, in a way, just to do with the timing of where I was in my life – I was, I suppose, second or third year of secondary school. It was the first time I had tiny bits of money, pocket money and this and that.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

How old would you have been? Thirteen, fourteen?

MARK WATSON:

Probably thirteen when it came out. I was just starting to listen to commercial radio off my own back, basically. We’d have GWR FM, the commercial station in Bristol, on the drive to school. My dad was a teacher, of course, so I had a lift, and in that 20-minute drive, you’d get maybe two songs around all of the chatter. But I’d be listening to other stuff on the same station when I’d be doing my homework, and I had no real idea how the station’s playlists worked or anything, so there’d be stuff I absolutely didn’t want to listen to at all, but occasionally you’d get a gem. And they played ‘Linger’ with, as far as I remember, no fanfare at all, but I just caught the band’s name.

I’d listened to a lot of R.E.M., my first proper band as a young teenager, so I liked that kind of folky pop sound, but I hadn’t really heard anything like this. Strings in pop songs would become ubiquitous later – The Verve, and Embrace and so on – and I’m still a real sucker for well-done strings in music, but there was a period in the 90s when you just couldn’t get away from it.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

And of course, Top of the Pops would have ‘the string section’ in the studio and you’d wonder, ‘Are they the string section on the record?’

MARK WATSON:

That’s right. It’d weird to look back on, but ‘string section’ was almost like a drum machine [setting] for a period – and I really took against ‘Bittersweet Symphony’ by The Verve later on…

JUSTIN LEWIS:

Although that one is a sample, isn’t it?

MARK WATSON:

That’s true actually – but also I think by the end of the 90s, that Irish folk tradition as pop music thing became slightly degraded by what I regard as lesser imitations of the Cranberries.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

When the Cranberries first emerged, they reminded me of the Cocteau Twins ‘but you could hear the words’, and I don’t mean they did that cynically. I’m trying not to use the word ‘ethereal’ but I just have.

MARK WATSON:

I had never heard anything quite like ‘Linger’ on first listen and, because of the way music was then, I remember wondering when I’d hear it again. There was no way of making it happen, necessarily. I didn’t know if it was even out. It’s very odd to look back on how random it was. Like, now, you can listen to any song that you want, any day, any moment, of your life. It’s funny to think of a time when you’d listen to the radio, wondering whether or not a song would come up.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

I used to listen to the Annie Nightingale Request Show on Radio 1 on Sunday nights in my teens, and that show was such a lifeline in terms of playing unexpected records. With request shows, now, people tend to request things that the station plays anyway, or the station chooses the requests that match what they already play. Or seems to, anyway. But on that show, it was completely up for grabs – you seemed to be allowed to choose anything, and that really freed things up.

MARK WATSON:

Yeah, I really like how BBC 6Music replicates the spirit of that by doing things like the People’s Playlist and the Cloudbusters. And I think Lauren Laverne is a sort of natural heir to Annie – among many other accolades I’d bestow on Laverne. But still, in the modern age, the request show is a strange concept because we all know there’s a much easier way to hear the song.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

True, although only if you know the song already. Annie’s way of doing it, which is fantastic, was apparently when people would send in lists of songs, she’d often investigate the ones she didn’t already know.

MARK WATSON:

That’s a bygone era in mainstream terms – even for 6Music, that would be pretty daring.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

Yeah, I really liked the idea that the audience could educate the broadcaster as well as vice versa.

MARK WATSON:

But because this was commercial radio, it was a case of waiting for ‘Linger’ to come along again. Once I’d heard it two or three times, I definitely felt I needed to know more about this band. I don’t think I’d quite started reading the NME or anything, I had no resources at all, so I just went to a music shop and see what was there. I went to Woolworths. I saw the album cover, I read the track listing, I saw ‘Linger’ was on it. I obviously didn’t know any of the other music on it, and I remember it felt like a substantial investment, £12.99 or whatever it would have been.

By that point, I had a little stereo of my own that I’d got as a birthday present and a pair of headphones, and so I was listening to music in quite a secretive, teenage kind of way. I still did listen to stuff with my dad, but I was also starting to get to that age where you wanted to discover stuff for yourself. I was aware of my taste starting to form separately. I remember around the same time hearing ‘Cornflake Girl’ by Tori Amos, one of the first moments of thinking, ‘I love this, but I don’t think my dad would be into this.’ Actually, in the end, he did quite like it, but then he did like Kate Bush, and I didn’t know about Kate Bush at the time, so I was wrong about that. But R.E.M. – albums like Out of Time and Automatic for the People – had come through him… and I knew he would like The Cranberries, but I also wanted to be the guy who discovered it.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

Oh, you’ve got to find this stuff for yourself, that’s how it works.

MARK WATSON:

Yeah, I remember listening to the album, thinking, ‘No-one knows about this yet. I’ve never heard anyone mention this band, apart from that time they got that fluke play on the radio.’ And then, not long after that, ‘Dreams’ was a very big radio hit. It would come on in the car [in the drive to school], and I would feel this pride that, for the first time in my life, I’d put my dad on to something musically. Before that, everything had come through him… or a couple of clued-up mates at school.

And it was a bonus that the Cranberries had such a distinctive female singer, Dolores O’Riordan. And then Stephen Street’s production – I found out years later (weirdly, after listening to the Smiths), I went back and realised it was the same guy who produced both, with that slick, jangly guitar sound.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

And straight after this Cranberries record, he went on to make Parklife with Blur.

MARK WATSON:

Yeah. I didn’t know his name, but I loved the sound of it. Even listening back yesterday, it’s very tightly produced, the drums sound great, and they’re very satisfying pop songs, but Dolores’ voice is the drawcard, obviously. She used to get compared to Sinead O’Connor, but I think that’s purely because it’s two fiery Irish women. There’s this lilting, hypnotic quality, but it can turn so quickly… there’s such melancholy in the voice in a song like ‘Linger’, but elsewhere the vocal is quite ferocious. And that in the end became the sound of ‘Zombie’, and when the sound got punkier, I started to part ways with the Cranberries. I think I had that classic teenage snob thing where once everyone at school knew ‘Zombie’, I was like, ‘Well, you guys don’t understand the Cranberries!’

JUSTIN LEWIS:

I must admit, when I heard the second album, I was thinking, ‘Yeah, I might be out, here’ – but I liked this first one a lot at the time.

MARK WATSON:

It did seem like diminishing returns.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

They were massive though. I note that on streaming, ‘Linger’ has passed one billion plays now. And ‘Dreams’ is not too far off that.

MARK WATSON:

Remarkable, yeah.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

But – I always find this kind of thing interesting – do you know who they supported live before they became big in their own right? Suede – not a massive surprise – but also Duran Duran on their US tour.

MARK WATSON:

That’s a strange partnership.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

And Dolores married Duran Duran’s tour manager, that’s how they met on that US tour. And I realised that’s partly how they got so big over there. Suede didn’t mean that much over there, but Duran Duran would have done.

MARK WATSON:

That’s fascinating – and also ‘Dreams’ became one of those songs that are in adverts. Like ‘Walk Away’ by Cast, which suddenly had a life of its own. And then there were songs that sound almost deliberately written like that, like ‘Going for Gold’ by Shed Seven. But in this case, with ‘Dreams’, it was just a fairly eccentric song tapping into the mainstream. Again, so much of it was her voice. Like there’s that weird wordless chorus where she’s just sort of howling, which is so different from the pop sensibility of something like ‘Linger’. You start to get a real palette, but also the songwriting and the melodies are so good. And I know that Dolores struggled with all sorts of aspects of being a globally famous pop star…

JUSTIN LEWIS:

Oh sure, I don’t think I could have coped with anything like that at all. That trajectory was dramatic, wasn’t it.

MARK WATSON:

Absolutely wild, but what’s nice – it’s still a very good listen, I think.

—-

JUSTIN LEWIS:

I’ve heard you mention in a few interviews how, perhaps unusually for a stand-up, you were driven more by music than comedy when you were in your teenage years. How did your music obsession grow, and how did you start to think you could do comedy? Was it becoming established as a performer?

MARK WATSON:

The pieces didn’t all fall together smoothly. I went to see a lot of bands live in my teens and well into my twenties. But the formative period for gig-going, in terms of my ambitions, was from about fourteen to twenty. Part of why I was much more into music than stand-up was there was nowhere near as much of a comedy scene in those days, or at least not one that anyone would know about. I would see the odd comedian at Bristol Hippodrome or the Old Vic. But even going to university, I could only have named about a dozen comedians, the same ones everyone knew – Victoria Wood, Lenny Henry, you know.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

And were you watching TV comedy at all?

MARK WATSON:

Yeah, although most of the comedy I watched was things like The Fast Show, The Simpsons, Harry Enfield… As with music, it was [an attempt to discover things] that my dad didn’t watch. The Fast Show was not something he’d have watched – that was my generation’s thing that we found for ourselves, I suppose.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

That was your Monty Python.

MARK WATSON:

That was our Monty Python, for sure. You’d go into school and recite the catchphrases… it was Friday nights and you’d look forward to it all day. But I had very little notion of what stand-ups were, I couldn’t picture in my head a comedy circuit, but then there was less of a circuit then. There were nowhere near as many touring comedians or clubs where I was – Bristol was quite well served for live entertainment, but I’d never seen someone just get up and do stand-up in a club environment, whereas I’d seen dozens of bands in these grungy rooms… I wasn’t musical myself – I played the drums a little bit, to no real avail, but something about watching the live music experience really did work for me. I couldn’t even drink legally when I was first going to gigs, but even though everywhere stank of smoke, I remember that environment really fondly. The anticipation building as the band’s arrival got closer… that feeling of the first song… and what used to be the stampede to the front when they played the big hit. I found all those things really intoxicating, not just the music but the whole live experience.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

Was there a particular group that you really associate with that formative time, that you’d have seen live around then?

MARK WATSON:

The Super Furry Animals were the big ones for me. My brother and I were big funs. I was fifteen or sixteen when Fuzzy Logic came out, and then Radiator, in fairly quick succession. We’d been into the early days of Britpop. Like we were not huge Oasis fans, liked Blur, liked Radiohead, Pulp, Pulp in particular. Like everyone who was fifteen at that point, though my brother was significantly younger, we were swept along by that Britpop wave.

But then Super Furry Animals just represented something different. The first time I came across them was when they were on Later with Jools Holland [BBC2, 01/06/1996]. They played ‘If You Don’t Want Me to Destroy You’ and I think ‘Hometown Unicorn’. I just remember I loved the band name, loved the names of the tracks, loved the look of Gruff Rhys and his air as a frontman. There was the fact that we had Welsh family and we grew up very near the Welsh border. We hadn’t seen a big Welsh band before… I mean, there’d been the Manics.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

When I was in my teens, it was a bit like that. The Alarm were quite big but they were from North Wales, the other end of the country from where I was. There seemed to be nobody from South Wales, and the ones who were from there, seemed to move away. Like Green Gartside – I didn’t know he was from Cardiff.

MARK WATSON:

I mean, the Manics went on to wear their Welshness quite proudly but it wasn’t what you thought of… you thought of them in army uniforms and stuff on Top of the Pops. I was basically quite scared of them, and of the people at school who were their fans. Whereas the Super Furries were in this perfect spot at that stage. It was just brilliant, hooky, catchy pop music – but also quite anarchic and strange.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

Yeah, I was from Wales already and there was a real mystery about them. I used to wonder, ‘Where’s this coming from?’

MARK WATSON:

There were lots of elements, not least the fact that I’ve read many interviews with Gruff. I remember him saying when they recorded Fuzzy Logic that he was basically singing in English almost for the first time. So a lot of how his vocal and his tone are so inimitable comes from the fact that it’s almost like someone’s singing in a foreign language or not quite singing in English or Welsh. And also the left-handed guitar, and the excesses of Dafydd the drummer, and it was like wild, druggy glam pop, but coming from guys from down the road.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

And to have a bilingual pop group in the first place – that had rarely happened before, really.

MARK WATSON:

It was exhilarating. Even by the second album, there were songs in Welsh. There were references in the album art, which contained references to photos of things like signs for Brains faggots, and stuff like that, and landmarks from Cardiff that we recognised living in Bristol. But at the same time, the songs were teeming with references to stuff that we didn’t have a fucking clue about. So they were just in that perfect space – it both spoke to me, and it was also from another planet.

But then, specifically, the reason they influenced me, and were so exciting live: they understood the show as a spectacle. They’d be in weird animal costumes, there’d be strange stuff on the stage, they experimented with surround sound and lights. And you went to see them lots and lots of times, every time, we’d travel all over the place to see them. You’d love the songs, but you always also felt it was going to be an hour and a half of absolute bedlam.

Fast-forwarding a bit, once I was at university, I still didn’t know anything about stand-up. I was just doing sketch comedy, I suppose trying to do the sort of stuff I’d seen in The Fast Show.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

Was this in Footlights?

MARK WATSON:

I was at Cambridge, but I was barely involved in Footlights because I was sort of intimidated by that heritage and mystique. I did some very small-scale stuff for Footlights, like the occasional one-off night they might put on, but I wasn’t part of the main body of it until right at the end. I had a mate, and we did sketches in college things, and we’d put informal nights on.

Gradually, I started to get interested in the idea of stand-up. The breakthrough for me, not professionally but mentally, was going to the Edinburgh Fringe in 2000, with a college society and a play that I’d written. Then in 2001, I went with the Footlights. And in both of those years, I went to see absolutely everything. I saw an enormous number of shows. It was a comedy education for me. Suddenly, I was seeing lots of stand-ups who were not yet household names, but in that Fringe way, a lot of them were quite heavily talked about.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

So in this period when you’re doing sketch comedy but also starting to write, you wrote a play with Tim Key which played in London, is that right?

MARK WATSON:

Yeah, it was 2002. It was called A Few Idiots Who Spoil it for Everyone Else. That was a two-hander. We were both getting into doing our own things. Tim went on to do all sorts of sketch stuff, but by now I had got a taste for stand-up, and I think sitting in those dark rooms in Edinburgh, there was that same feeling of anticipation, waiting for a comic to come onstage and being [positioned] so close to them. That shared live experience reminded me of the same thing I’d felt five years earlier when I first started going to see live music. And by now, I felt I was watching something which I could possibly aspire to do myself because I could talk.

So something happened in my brain around then, 2001, 2002. I liked the art form, I liked the idea of being able to do something unlike a sketch show – you could just pop up on stage and do exactly what came into your head. All that was attractive to me, but without a doubt, part of me was also thinking, ‘This is like a rock show in a way.’ Even now, I still get a kick out of it when I’m playing a venue which I remember being on a poster on my wall from the NME, like the Sheffield Leadmill, you know… there’s been a handful of venues I’ve played that once would have been on bands’ touring posters. That is nice.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

It’s striking to me how your first novel [Bullet Points] came out when you were 23, 24, the sort of age when a musician might release a debut album. Quite young, really.

MARK WATSON:

Yeah, and that’s because writing had been my real ambition – stand-up was something that kind of ambushed me. Writing books was what I wanted to do, even at university, I was quite serious about that. Again, I was influenced by musicians – as you say, I had an awareness that many musicians did bring out their work very early. Of course, it’s quite a different trajectory for a lot of authors; a lot of authors don’t peak till their sixties. ‘Enfant terrible’ is not quite the right phrase, but I wanted to be the equivalent of a band bringing out albums at 22. Some of the bands Britpop brought up were, with hindsight, unbelievably young. Supergrass were basically teenagers – and Ash of course. That’s funny, looking back, because that first Ash album [1977] was full of nostalgic songs about young love, like ‘Oh Yeah’ and ‘Goldfinger’… but they were only, like, eighteen themselves. From my vantage point of my mid-forties, it’s very funny to hear, and there are some really good songs on that first album, but it’s funny that they could barely have experienced any of that.

But yeah, I wanted to be, like, a young sensation. I don’t think I consciously framed the thought that way, but I wanted to be the next big thing. Which worked for me as a stand-up, but it worked against me as an author, a bit, because that first novel didn’t really do anything, and it wasn’t great. It had come a bit too early.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

Got some very good press at the time! I was really interested to revisit some of that.

MARK WATSON:

There was certainly quite a bit of hype but for whatever reason, it never really took off – and once you’ve had that kind of false start, it’s very difficult. You don’t get to be ‘the first novelist’ again, for sure. I always say to people when they’re struggling to get published and it feels impossible in a way, ‘Be careful what you wish for’, because being ‘the new thing’ can only happen once. At least with stand-up, I had a longer grace period because it just so happened that stand-up was becoming really vogueish at exactly the time that I was getting into it. It’s a bit of a crude parallel but being a stand-up in the 2000s was a bit like being Britpop in the nineties. Loads of press…

JUSTIN LEWIS:

Probably a comedy club in every town…

MARK WATSON:

There were clubs everywhere… Edinburgh Fringe felt a bit like a rock festival, so things really conspired in my favour, stand-up wise. But I came to realise over time that many artists I admire have had longevity rather than being hyped in their twenties. R.E.M. are not active anymore, but they produced a body of work over thirty years.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

And they’re still individually doing things, musical projects, not in a high-profile way, admittedly.

MARK WATSON:

Same with Gruff Rhys… still enormously productive, and the Super Furries are touring again next year to my disbelief. But what I didn’t appreciate in my early twenties, with that NME culture, and the hype around ‘the new thing’, both as a consumer of art and as someone trying to make stuff, you come to appreciate the long game.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

Another parallel with music, it occurred to me, are those 24-hour shows you used to do at Edinburgh. I think you even did a 36-hour one at one point. Is it about using that space, having that kind of atmosphere, creating a kind of event?

MARK WATSON:

I mean, when I did the first 24-hour show [2004], I had no profile as a comedian at all, not even in Edinburgh. So it was quite a hubristic thing to do. But I had been thinking, What can I make that would be a special experience for people? And I remember saying, ‘Why has no-one ever done a 24-hour long show?’ And of course, there’s loads of good reasons, but once you’ve thought of it, you sort of have to do it. But once it had become a talked-about thing, the ones I did in subsequent years, it was a bit more like being an indie sensation. I relished that people were, like, ‘Oh – is he going to do another long show? What’s it going to be like this time?’ Again, I suppose the more you mythologise yourself as a pop star, the easier, the more parallels you can find. But my career in Edinburgh, throughout the second half of my twenties was quite a lot like making a second, third, fourth album… your following’s growing, but you’re starting to be forced to put out more work than you can ensure the quality of. I was doing TV shows I didn’t necessarily feel comfortable in. I wasn’t Pulp suddenly finding themselves in front of 40,000 people at Glastonbury, but I did feel wildly excited by the upward trajectory, and at a certain point realising I wasn’t really in control of this. And the integrity I started out with was in danger of being lost, because I had ambitious management, I was saying yes to everything, out of curiosity as much as anything.

But what I really like about my career now is I only really do things that I believe in and want to do as projects. Twenty years in, and again, I’ve learned this largely from musicians: you still have to make a living, but you start to think, ‘I’m not around forever, what would I like my body of work to be?’

JUSTIN LEWIS:

Reading your memoir, Mortification, I was struck by how you’ve realised there’s no point comparing yourself to other people. Partly because they will often have a completely different agenda to you anyway.

MARK WATSON:

Yeah, you never know what’s going on with them. If you are relatively happy and content, then you are doing better than a lot of people, whether you think so or not.

—–

LAST: JONATHAN RICHMAN & THE MODERN LOVERS: Jonathan Sings! (1983, Sire Records)

Extract: ‘The Neighbors’

JUSTIN LEWIS:

Not something I would have expected as a recent record!

MARK WATSON:

Well, no. What happened was Jonathan Richman passed me by for most of my life, although I remember seeing him on Later with Jools Holland as well in the 90s. Jools was a real resource in those days – you could rely on seeing something nearly every week that you wanted to explore. The story with this is simply that I was in a venue earlier this year, and I heard ‘I Was Dancing in the Lesbian Bar’ [from I, Jonathan, 1992] – almost the only Jonathan Richman song I knew, I think. And I was reminded of how fun it is, what an exuberant, silly song it is. It put me in a very good mood, and in an idle moment, I thought I should really look into Jonathan Richman a bit more.

Like a lot of artists, he’d been on the periphery of my awareness… in the 90s I used to listen to a band called Hefner, and they covered the Jonathan Richman song ‘To Hide a Little Thought’. So every few years, his name somehow came up but I realised I’d never done any serious work on this guy, so I googled his body of work, looked at what were regarded as the essential albums (in fact I actually asked Darren Hayman from Hefner on Bluesky), and downloaded the Modern Lovers album, Jonathan Sings! – and straight away was hooked.

What I love about it is, this is music I could never have got into when it was first out – I’m a bit young for a start, but also I don’t know if I’d have gone near this kind of rock’n’roll sound in the 90s. There’s a lack of irony about it, a glee in the music.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

There’s an innocence to it.

MARK WATSON:

Yeah. I think I would have found it very uncool as a teenager. But the thing is, it is uncool – that’s the beauty. Even if I’d seen that now-famous clip of him playing ‘I Was Dancing in the Lesbian Bar’ on Late Night with Conan O’Brien… [NBC, 16/09/1993] in my twenties, it was very far from the sort of thig I liked. Now, I think it’s a perfect, pure example of performance. It’s just him and the audience – he’s just messing around, but like every clip I’ve ever seen of him, he just looks like he’s delighted to be on stage. And he’s always interjecting, interrupting his own songs, Mark E. Smith’s another one who did that. There’s a real freshness to it.

But on this particular album, Jonathan Sings!, there are two or three really silly songs, like playground anthems, and then the third track, ‘The Neighbors’, is a really funny, ambiguous example of something like ‘Baby It’s Cold Outside’, that sub-genre of songs about whether or not someone should stay the night. I love the way he keeps muttering ‘You see what I mean?’ – and ‘Of course not’. The song is almost a conversation, but it’s got these beautiful female vocal parts, the melody itself – across the album, there’s this goofy rock’n’roll but also these unexpectedly delicate arrangements.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

With all the interruptions he does to his own songs, he does remind me of a stand-up, funnily enough. I was thinking of someone like Emo Phillips.

MARK WATSON:

That’s quite a good comparison – maybe Emo Phillips was inspired by Jonathan Richman. Emo Phillips is someone I saw, early doors, at the Edinburgh Fringe, and as much as anyone inspired me to think, ‘Wow, so you can just do this, can you?’ I remember Jonathan Richman saying, ‘I don’t really write the songs, I kind of make things up.’ Even in that Conan clip, he prefaces it by saying, ‘I’m going to tell you a story which happened to me recently, and then just goes into the song. Performance-wise, it feels like where spoken word meets music. A lot of artists aspire to that sort of cosiness with the audience, but it’s quite hard to be as unaffected as he is.

But the more I delve into the back catalogue, as well as the whimsy, there’s also some really beautiful love songs. ‘Somebody To Hold Me’ on this album is quite naïve and borderline saccharine, but the music’s beautiful and the lyrics are full of unexpected reflections. It really lands in the sweet spot for me, between the kind of playfulness I like and these moments that pierce you when you’re not expecting it.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

He has said that he likes appealing to all ages. Though I don’t think he’s actually made a kids’ album like, say, They Might Be Giants did, he’s definitely got that sort of approach. I found a great quote – he got reviewed once with the words: ‘It’s great that Jonathan Richman wants to be rock’s great innocent, but does that mean he has to sound like he hasn’t been toilet-trained yet? Somebody point this guy towards Sesame Street!’ [MW laughs] Now, the thing is, he absolutely loved that review. When it was suggested, ‘But you’re not very mature’, he replied something like, ‘No, I’d prefer to be regarded as infantile in a way’ – I suppose because as a kid, you are liberated, you can make up your own stuff before you have to start to conform.

MARK WATSON:

Yeah, that’s right, a lot of his songs do sound like that. It can be too much at times, for example, the song on this album from the point of view of a three-year-old… that’s probably too much for me. It’s still quite a nice tune, it’s a clever conceit for a song, but I don’t really want to hear a grown man singing as a toddler. But I love that he’s still doing it, he put an album out this year, I think. By the look of it, he’s never stopped. He had that ‘young rocker’ era, the ‘weird cult figure’ audience.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

I think acquiring the There’s Something About Mary audience probably helped as well.

MARK WATSON:

I’m sure, yeah. So he’s lived a life, but there’s something really edifying about seeing a guy in his seventies still making a record every couple of years and touring America, purely because he wants to. But what’s rewarding for me with his stuff is, so much new music is coming at you the whole time, like you said earlier, and sometimes it feels impossible to keep pace with it… so now and again, it’s really refreshing to encounter something from the 70s or 80s which you also never knew. It just re-sets you, it reminds you that you can never be across all the music anyway.

—-

ANYTHING: NEW PORNOGRAPHERS: Twin Cinema (2005, Mint/Matador Records)

Extract: ‘The Bleeding Heart Show’

MARK WATSON:

This brings together some of the themes of this conversation. I discovered this band in my mid-twenties, when they were on this third album, Twin Cinema. It was another random recommendation, a ‘you might also like’ type of situation, because I was listening to some other power pop-style bands at the time, things like Death Cab for Cutie. There was a glowing review of this album in Pitchfork, and at that age, 26, 27, I had a very high regard for Pitchfork. I was exactly the sort of person who would only have listened to them at that stage of my life, I was thinking, ‘Well they were right about Grizzly Bear’.

So I downloaded this album, knowing nothing about the band, and almost instantly, I loved it. I went on to listen to the previous two albums, I became a huge fan, and I’ve listened to them a lot over the past 18 years or so. The music is exactly in my ideal zone – this sort of melodic pop sensibility, the craftsmanship of the music, the lyrics, all of it. And they are popular among a certain type of music fan, and are a well-respected name, but you don’t often meet many people who’ve listened to them.

Carl Newman – or AC Newman as he’s often known – talks really interestingly about some of the things we’ve been talking about. What it was like to be part of a wave of hype and popularity twenty years ago and how now… they’re still making records, he makes loads of music… by any measure, he’s a very successful musician with a devoted fanbase of people like me. But it’s a relatively niche form of famous, so I’ve learned a lot of lessons from that. There are times when I feel as if – as I talk about in Mortification – I’ve not made the impact that I would like, or I’ve put out a book that doesn’t sell many copies. And then I’ll think of a band like New Pornographers and think that often, to somebody like me, that’s their favourite work, the thing they get the most out of.

I mean, Super Furries were always sort of a niche concern, as well, I suppose, although by the time they called it a day, I was watching them in big spaces, they’d be headlining at festivals. I was a big Radiohead fan – I am a big Radiohead fan – I’ve watched them become global icons. I’ve followed Tame Impala from the fringy, Aussie weirdo days to a bizarre level of fame. But with New Pornographers, this is an example of a band that, in my head, have got bigger and bigger and bigger because with every album they’ve put out, I’ve loved them that bit more – although that isn’t matched by the real world, though they continue to be very critically successful and still tour the US and Canada extensively.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

And all the members seem to be in lots of side projects, don’t they?

MARK WATSON:

It’s another thing I find attractive about it. Most bands that I grew up listening were very much traditional four-piece outfit, but because New Pornographers originated as a so-called supergroup, they’ve always had a flexible line-up. So there are different songwriters, different vocalists, something else the Super Furries had. A lot of my favourite acts have had different voices in the mix. But this is an extreme example of that because you had Neko Case and Carl Newman, and then Dan Bejar, this kind of maverick who dives in when he feels like it. I couldn’t remember hearing an album like this before where you have three different vocalists.

Nowadays, it’s more Newman’s project, I suppose because he’s the consistent force, but even when they tour, you don’t know exactly which members will be there, which I suppose has its frustrations, but it’s part of the reason why the music’s so good because there’s a sort of egolessness to it. That said, there’ve been bands where the line-ups have changed so much that it’s a kind of Ship of Theseus situation where it doesn’t really mean anything anymore. But because you’ve always got Carl Newman, you’ve always got a frontman, and sometimes he’ll slot in a saxophonist, or on the album before last, a string quartet. It’s like the sound of the album is driven by what musicians are available to play at that moment.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

It’s interesting when you see people working in lots of different spaces and collaborating like that. Oddly, you get a lot of that at the most commercial end of pop now: Famous Artist teams up with Famous Artists, featuring Other Famous Artist for a new single. That seems to happen all the time. But it also made me think of a figure like Jenny Lewis – her discography is just bewildering because she seems to have done so many things. It’s like being an actor or something.

MARK WATSON:

Yeah, that’s right. A good example of that is how the first incarnation of Tame Impala I came across was this guy [Kevin Parker] fronting a psychedelic rock band, and that same guy is now the producer for people like Dua Lipa. It feels like we live in an age, including for lots of reasons to do with the Internet, where collaboration seems like a complete free for all. And going back to Carl Newman, like Gruff Rhys, Michael Stipe as well… I’ve always loved musicians who seem to tinker for the fun of it, who just put stuff out that you might not even notice. We lived through a period where bands would have enormous record deals and were under contract to make a certain number of albums. We don’t live in that landscape anymore.

That said, I have a lot of respect for people like Portishead, who I’m a big fan of, who take years to perfect a project, but I’ve always loved people who are just firing a lot of stuff out there, taking chances, making unexpected projects.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

There are some groups where it’s easier to be a completist.

MARK WATSON:

It’s fairly easy to be a Portishead completist.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

It’s pretty easy to be a Blue Nile completist. With other people, it’s harder.

MARK WATSON:

Because with the New Pornographers, you’ve got their eight or nine studio albums, but then Newman’s released three of his own, Neko Case has loads of her solo stuff, Dan Bejar’s main group is Destroyer and that’s a whole separate canon of work. This kind of thing is either a music junkie’s dream or it’s a nightmare because while it’s great to keep discovering new stuff, you simply cannot get on top of all of it. There’s only so much time in the day.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

Would Twin Cinema be a good starting point for New Pornographers newcomers?

MARK WATSON:

Yeah, it’s a brilliant, accessible pop album, drenched in hooks. The first album is often seen as the definitive one – the song ‘Letter from an Occupant’ was as close as they’ve come to a big hit – that and ‘Use It’ from this album. But for me, the whole body of work stands up fantastically which I’d recommend to anyone that likes guitar music, basically.

—

JUSTIN LEWIS:

I’ve been really enjoying your new novel, called One Minute Away, about a delivery rider in London and how he connects with one particular customer. The last novel you had out, Contacts, was about a desperate man messaging everyone in his contacts book and their various reactions. These are really interesting scenarios for stories, which a lot of people could relate to, but I’m struck by how they have a very different voice to your stand-up work. And I was wondering how you decide between whether something is a show or a routine, or whether it’s a long-form novel. Do you have false starts when you’re trying to decide that?

MARK WATSON:

Sometimes. In the end it works itself out because there can be territory that I try and explore on stage, and I just can’t work out how to make it funny, or it’s just too complex or dense. With One Minute Away, I’d been wanting write a novel about the gig economy and the food delivery business for years, because I had the odd joke about it, but I hadn’t been able to explore that before. The shortest explanation, probably, is that novels are what happens when there is something nagging away, and I can’t make it funny in a sustainable enough way. Or it gets into territory which is too dark for a stand-up show. As a stand-up, I do feel that responsibility to entertain all the way along.

It’s also quite important to me that the books do sound different from my stand-up – a lot of comedians write books which are more or less an extension of their stage work. But I see the two things as different disciplines, and I guess I want people to read the books without necessarily knowing that I’m a comedian. But the novel I’m working on at the moment is probably closer to my stand-up voice than anything I’ve done before.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

I discovered you did a daily show at the Edinburgh Festival in 2006 called Mark Watson and His Audience Write a Novel. Was it like a workshop?

MARK WATSON:

Yeah, that was an unworkable idea, but it was quite a fun show. We’d get together and brainstorm. We’d work together on it for an hour, then I’d go away, write the next chapter, come back to the next audience.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

It’s a bit like that game, Consequences, isn’t it?

MARK WATSON:

Yeah. I could just about keep up with the workload, and it worked quite well as a gimmick, but it’s not a recommended way of writing an actual good novel, obviously.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

And it’s a hell of a lot of work in between each show.

MARK WATSON:

It was. Twenty years ago, I had an absolutely unquenchable appetite for that sort of work. But the irregularities of the plot became impossible to tame because people were throwing in more elements which didn’t make sense. Because it was still me writing up every chapter, I could keep some sort of central narrative. But by about halfway through the run, I realised, This will never actually be a novel because this is not how you write a book.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

It’s interesting for the audience to have that insight into working methods, I would think. Although how would you deal with royalties, had it been finished and come out?

MARK WATSON:

Well, that’s the thing. There were lots of good reasons why it couldn’t have been a published novel. Among them: 500 people have collaborated on it.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

Who’s going to get the PLR royalties there?

MARK WATSON:

As we know, there’s barely enough to go round for one person.

—–

Mark Watson’s One Minute Away is out now, published by HarperCollins.

His latest live stand-up show, Mark Watson: Before It Overtakes Us, continues touring well into 2026, and you can find further details and ticket links on his website: https://www.markwatsonthecomedian.com

You can follow Mark on Bluesky at @watsoncomedian.bsky.social.

—–

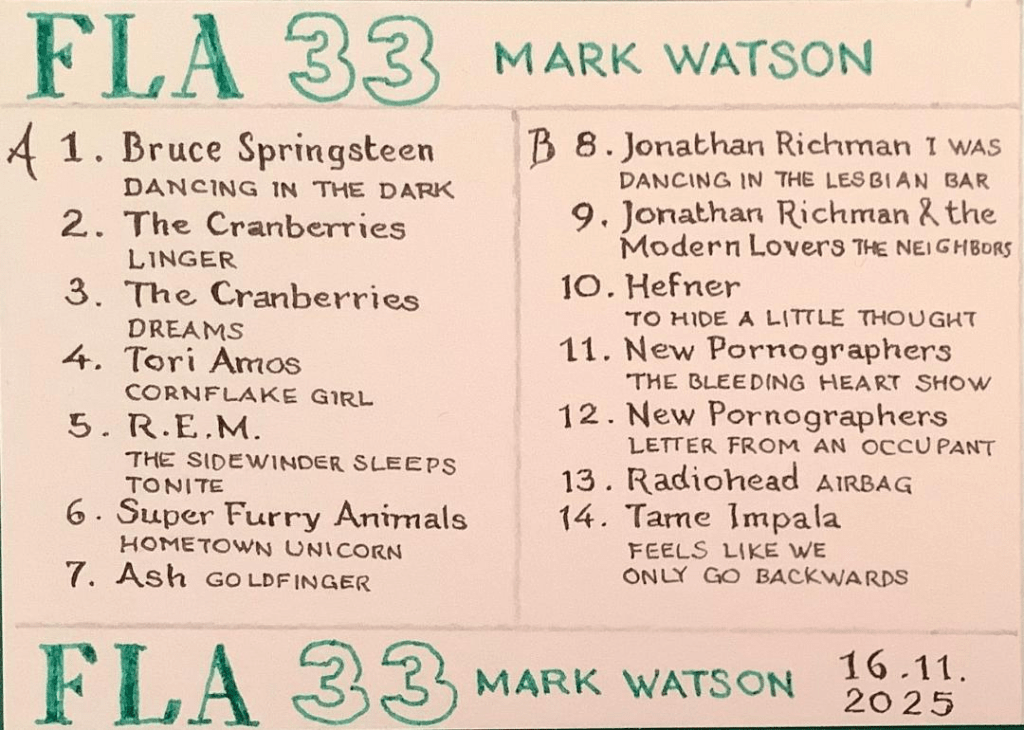

FLA 33 PLAYLIST

Mark Watson

NB: Track 10: Hefner’s cover version of Jonathan Richman’s ‘To Hide a Little Thought’ is currently unavailable on streaming services, but will be added to the playlists should the situation change in the future. The YouTube link will be included in the list of tracks below.

(For the time being, this site and project uses Spotify for the conversation playlists, but obviously I disapprove that Spotify doesn’t pay artists and composers properly, and other streaming platforms are available, as are sites to buy downloads and buy recordings. For consistency, you can also listen to the selections via YouTube (where available), and links are provided in each case, below.)

Thanks to Tune My Music, you can also transfer this playlist to the platform or site of your choice by using this link: https://www.tunemymusic.com/share/wGiYXXFESQ

Track 1:

BRUCE SPRINGSTEEN: ‘Dancing in the Dark’:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=129kuDCQtHs&list=RD129kuDCQtHs&start_radio=1

Track 2:

THE CRANBERRIES: ‘Linger’:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=G6Kspj3OO0s&list=RDG6Kspj3OO0s&start_radio=1

Track 3:

THE CRANBERRIES: ‘Dreams’:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Yam5uK6e-bQ&list=RDYam5uK6e-bQ&start_radio=1

Track 4:

TORI AMOS: ‘Cornflake Girl’:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tfC0-pVpQWw&list=RDtfC0-pVpQWw&start_radio=1

Track 5:

R.E.M.: ‘The Sidewinder Sleeps Tonite’:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mgiCechWNCo&list=RDmgiCechWNCo&start_radio=1

Track 6:

SUPER FURRY ANIMALS: ‘Hometown Unicorn’:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_zxXF0B_SyM&list=RD_zxXF0B_SyM&start_radio=1

Track 7:

ASH: ‘Goldfinger’:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VEKp-nvVn6I&list=RDVEKp-nvVn6I&start_radio=1

Track 8:

JONATHAN RICHMAN: ‘I Was Dancing in the Lesbian Bar’:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qTLsfZk-FpE&list=RDqTLsfZk-FpE&start_radio=1

Track 9:

JONATHAN RICHMAN & THE MODERN LOVERS: ‘The Neighbors’:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IU7MkgF5IwU&list=RDIU7MkgF5IwU&start_radio=1

Track 10:

HEFNER: ‘To Hide a Little Thought’:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mO7c6OphdnY&list=RDmO7c6OphdnY&start_radio=1

Track 11:

NEW PORNOGRAPHERS: ‘The Bleeding Heart Show’:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yXi56azb6b4&list=RDyXi56azb6b4&start_radio=1

Track 12:

NEW PORNOGRAPHERS: ‘Letter from an Occupant’:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wCc_8HuWlQo&list=RDwCc_8HuWlQo&start_radio=1

Track 13:

RADIOHEAD: ‘Airbag’:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jNY_wLukVW0&list=RDjNY_wLukVW0&start_radio=1

Track 14:

TAME IMPALA: ‘Feels Like We Only Go Backwards’:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wycjnCCgUes&list=RDwycjnCCgUes&start_radio=1