As a first-year university student, one of the first songs of the 1990s I cherished was ‘De-Luxe’ by the London-based quartet Lush, who were signed to the independent record label 4AD. I was in the habit of taping Annie Nightingale’s Sunday night programme on BBC Radio 1 at the time, and I’m pretty sure that’s where I first heard it. It opened their first EP, Mad Love, and I quickly bought that on CD. I wasn’t a particularly big follower of indie-rock at the time, though I liked The Sundays and Pixies and the Cocteau Twins, but there was something about the sound of Lush that drew me in.

Lush – co-founded by Emma Anderson and Miki Berenyi, and completed by bass guitarist Steve Rippon (succeeded by Phil King from 1992) and drummer Chris Acland – had already released a mini-album called Scar (1989), and they went on to issue a compilation of their early EPs (Gala, 1990), and three full-length albums: Spooky (1992), Split (1994) and Lovelife (1996). A relentless touring schedule, and especially the unexpected and devastating suicide of Chris Acland in October 1996, hastened the end of the group. Emma Anderson formed a new duo in the late 1990s, Sing-Sing, with singer Lisa O’Neill, and made two (in my opinion) undervalued albums. But in the past few years, Emma has re-emerged in her own right with the terrific album Pearlies (2023).

Emma and I connected via social media a while back, and I had wanted to talk to her for this series for some time, especially after I heard Pearlies. I was thrilled when she accepted my invitation. A new reissue of Lush’s Gala in November 2025 seemed an opportune time for us to chat at length on Zoom one Sunday about first, last and wildcard recordings, and it was in that same month that 4AD uploaded Phil King’s film of Lush footage, Lush: A Far from Home Movie, to YouTube. The 35-minute film is fondly dedicated to Chris Acland’s memory.

—–

JUSTIN LEWIS:

I always start with this question. I’m aware you had a slightly unusual upbringing, which we’ll come to, but what music did you have in your home early on?

EMMA ANDERSON:

This was probably before we owned a record player, but I had one of those mono tape recorders with the buttons at the front which were probably really meant for recording speech, and I used to tape stuff off the telly.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

Oh, I used to do this.

EMMA ANDERSON:

I think a lot of people did!

JUSTIN LEWIS:

Before there were video recorders.

EMMA ANDERSON:

And your parents would walk in and start talking over it, and you’d go, [loud whisper] “Be quiet!”. But I used to tape stuff mainly off Top of the Pops and the Eurovision Song Contest.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

The Eurovision Song Contest, prior to things like Live Aid, was the most amount of music you’d see on TV in one go, really. You’d get three hours once a year. And it was also television from another country, quite often, there didn’t seem to be a house style for Eurovision like you tend to get for it now.

EMMA ANDERSON:

I also liked Eurovision because as a kid I loved geography, maps and stamp collecting and the rest of it [laughs] so Eurovision kind of fed into that. I collected all these cassettes of Eurovision which I used to listen to repeatedly.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

I had a black and white TV in my room, from about the age of eight – an extravagance, I soon discovered – and am I right in saying you did too?

EMMA ANDERSON:

Yes, and the reason for that was, my dad was the secretary of a gentleman’s forces club in Mayfair and the flat we lived in was part of the building. Needless to say, it was a strange place for a child to grow up. We moved there when I was about three and we left when I was about fifteen so that’s quite a big chunk of my childhood. The flat came with the job and in the same building were hotel-like rooms which members could stay in, and all these rooms had rental TVs in them. So, my parents didn’t pay for the two rental TVs in our flat, they were paid for by the club as part of a deal, I guess.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

The reason I asked about a TV in your room was because of the possible relationship with the technology. The reason I had one… we weren’t rich, but I was a complete TV obsessive in those days, and it was a window on the world, and I did learn a lot from it.

EMMA ANDERSON:

I did watch a lot of TV and I was an only child as well so I consumed a lot of not just pop music but culture and films… I was quite unsupervised too so was even able used to sit up late and watch horror films which were on quite a lot in the 1970s!

The other thing was, because we lived in the club, and a lot of the members didn’t live in London, they’d come in from the Home Counties and they’d visit our flat and sit and a have a drink in the living room with my parents. So another reason to keep me occupied in my room was because there were constantly guests around and my parents wanted to keep me away from ‘the adults’.

It was an unusual, atypical upbringing. I didn’t live in a normal house in a normal street in somewhere like Dorking, if you see what I mean.

—–

EMMA ANDERSON:

Going back to ‘tech’(or lack of it!), I do remember having a toy record player when I was quite small, I think an aunt might have given it to me. It only took 78s and it came with its own records and the two I remember were ‘Tea for Two’ and ‘Doing the Lambeth Walk’! [Laughs]. It was not a technological marvel; it had one of those massive needles. But then, we got a ‘real’ record player (sort of) – my mother was quite a heavy smoker, she smoked Embassy cigarettes, which came with these little vouchers in the pack. She saved all these up in a jar, and there was a catalogue you could from and ‘pay’ with the vouchers so we got the record player like that. I must have been about ten.

To be honest, my parents weren’t massively into music; they were from a different era. My dad was born in 1919 [laughs], and my mum was born in 1928. He was forty-eight and she was thirty-eight when I was born both of which, of course, these days doesn’t seem that old…….

JUSTIN LEWIS:

…But in those days, it would have been.

EMMA ANDERSON:

Yes, and I was adopted too (that’s another story for another time). Both my parents had been married before they were with each other and their heydays were from a time before popular music as we know it now, I suppose. I think there’s a watershed time where people’s teenage years and twenties were before the Sixties and The Beatles and so on.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

Well, in your dad’s case, it would have been before the word ‘teenager’ even existed. That wasn’t a thing.

EMMA ANDERSON:

Exactly. They did buy some records when we got this record player, though: my dad bought some Edith Piaf. He liked classical too classical but popular classical – eg A Little Night Music by Mozart…

JUSTIN LEWIS:

I mean, Radio 2 in the Seventies – and Radio 4, actually – would play popular classical music.

EMMA ANDERSON:

Yes, obviously they catered to a different demographic then. My mother also bought some records, She loved Frankie Vaughan but also The Ink Spots and Nat ‘King’ Cole’… Those are the ones I really remember.

—–

FIRST: LA BELLE EPOQUE: ‘Black is Black’ (1977, single, Harvest Records)

JUSTIN LEWIS:

It’s occurred to me there was this period in the mid-to-late 70s when there are these disco remakes of 60s hits. That version of ‘Don’t Let Me Be Misunderstood’ by Santa Esmeralda, and ‘Painter Man’ and ‘Sunny’ by Boney M, and even ‘Macarthur Park’ by Donna Summer, like quite a European disco take on 60s music. And then there’s this.

EMMA ANDERSON:

I didn’t know, until I was going to do this interview, that ‘Black is Black’ was a cover. And the song was only about ten years old at the time – you know if you had someone today doing a cover from something in 2015, it wouldn’t feel that long ago.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

Yes, They were Spanish, Los Bravos who did the original of ‘Black is Black’ – although it was Johnny Hallyday who had the big hit in France with it, so maybe La Belle Epoque took their cue from that version.

EMMA ANDERSON:

There was a record shop near where I lived, and I bought this there. What else from that time? Baccara, ‘Yes Sir I Can Boogie’, ‘Silver Lady’ by David Soul.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

This is all literally from the same few weeks, autumn ’77.

EMMA ANDERSON:

Oh ha – maybe I bought them all at the same time. And then – slightly later I remember buying ‘Northern Lights’ by Renaissance and we had the Grease soundtrack album. This feels like quite a strange thing for a ten- or eleven-year-old child to have, but I bought a Gladys Knight and the Pips album, Still Together.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

She’s quite underrated, I think, she’s got a brilliant voice. Sifting through all the interviews you’ve done over the years, I was reading how you started reading Smash Hits, around the same time I did, in the very early 80s. And it feels odd to think now that, in those days, they had a section on indie, the independent charts, they’d write about people like Crass.

EMMA ANDERSON:

Yes, the first one I bought [25 June 1981] had Kirsty MacColl on the cover and it had a feature on Crass, a review of Cabaret Voltaire. I was obviously into pop, but I was fascinated by the indie page as well. I am planning on seeing Cabaret Voltaire live next year, funnily enough.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

I inherited my first several issues of Smash Hits from my cousin Philip, who’s five years older than me, he happened to be getting rid of them, and I asked if I could have them. I think the earliest issue had the Undertones on the cover [26 June 1980], and there were all these references in it to Joy Division, because Ian Curtis had just died, but it took a while to work that out because I wasn’t a John Peel listener or anything like that.

EMMA ANDERSON:

It’s funny you mention The Undertones because in 1981, getting into more ‘alternative’ music (though still in the Top 40) really started for me and I bought ‘It’s Going to Happen!’ by The Undertones, ‘Treason’ by The Teardrop Explodes, ‘Sound of the Crowd’ by The Human League, and ‘Everything’s Gone Green’ by New Order. And I can tell you where I got ‘Everything’s Gone Green’ from – we lived on Half Moon Street, just off Piccadilly, and at the Curzon Street end there was a newsagent’s which sold ex-jukebox singles really cheaply – you could tell because the middle was knocked out. I had no idea who New Order or Joy Division were at this point in time. I had just heard the song in the Top 40.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

At what point did you start to think, ‘Maybe I could do this? Maybe I could be in bands?’ Because you were going to gigs, right?

EMMA ANDERSON:

The first gig I went to was Japan, supported by Blancmange [Hammersmith Odeon, 23 December 1981], and then The Teardrop Explodes…

JUSTIN LEWIS:

Was that when the Ravishing Beauties were supporting?

EMMA ANDERSON:

That’s right, with Virginia Astley – and I remember Julian Cope poured honey all over his body in the encore. There was also Soft Cell. Echo and the Bunnymen – but I also saw Haircut One Hundred and Duran Duran, the more poppy end. ABC, I saw. My friends went to see Spandau Ballet, I had a ticket for that, but I was ill and I couldn’t go and I was gutted.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

And this is still early 1980s, before these groups are playing arenas. They’re playing theatres.

EMMA ANDERSON:

I saw Duran Duran, Japan, ABC and Haircut One Hundred at the Hammersmith Odeon. Teardrop Explodes, Soft Cell, Bunnymen, U2, were all at the Hammersmith Palais.. I saw Simple Minds at the Lyceum… these were fairly sizeable venues but compared to where some of them they went on to play… quite small, yes.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

I can’t bear arena gigs, for the most part.

EMMA ANDERSON:

No, I can’t. At these gigs, we’d run down to the front of the venue when the doors opened and so we’d watch the whole of the support band. But you were asking ‘What made you think you could do this?’ Later on, I started to go to a lot more gigs in the back of pubs – and that’s when I started to think about that. Because it was a more DIY/post-punk environment, and you started to get to know people, especially in London when you’d get used to going to a huge number of gigs. Because it wasn’t glossy, the stage might only be a few inches off the floor. There was quite a community and in that era of late 80s London, people were squatting, a lot of people in bands were signing on – you could live in London cheaply. Camden and Notting Hill even were full of squats – hard to believe now, obviously. East London too – Hackney, Stoke Newington – and Brixton as well. But in that environment, you could pick up a guitar, bass or drumkit, and have a go. It’s a lot harder now.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

Oh god yeah. I don’t know how anyone gets started now.

—-

JUSTIN LEWIS:

Before you and Miki Berenyi formed Lush, around 1987 you were both in separate bands playing bass, right?

EMMA ANDERSON:

Yeah, they were both kind of rockabilly/garage groups (before what ‘garage’ means now!). I was asked to join The Rover Girls. They’d done a lot of gigs without a bass player already then I think they thought, ‘actually, I think we need one’. We did a few covers in that band (actually it all bordered on cabaret a little) – we did things like ‘Folsom Prison Blues’ and ‘These Boots Are Made for Walkin’’. One of our original songs was called ‘I Fell in Love with a Kebab Man’ – which I had no hand in writing, I should add! It was a bit of fun really.

When we formed Lush originally, we were a five-piece. As you probably know, there was another singer, Meriel [Barham, who later joined Pale Saints]. We played a lot of gigs on the London circuit, supporting a lot of people, and then after Meriel left, the songwriting changed a bit.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

It feels like things started to happen quite quickly after ’88, you get signed to 4AD, you get to make a mini-album [Scar] in ‘89.

EMMA ANDERSON:

Personally, I don’t think it happened particularly quickly. I mean, you heard of bands like Flowered Up who played two gigs or whatever who ended up on the cover of Melody Maker. I do consider that we did pay our dues. We played in a lot of pubs supporting a lot of bands!

JUSTIN LEWIS:

I suppose I was just thinking in terms of how the priorities of the independent sector change completely during the career span of Lush (1988–96) because the definition of ‘indie guitar music’ changed. And it must have been a thrill to sign to 4AD because I know you were a fan of a lot of the bands.

EMMA ANDERSON:

Oh, I was a massive fan. It’s not a secret!

JUSTIN LEWIS:

And the sleeve art for 4AD releases just looked so special. I’ve never quite understood when people say, ‘As long as the music’s great, that’s all that matters’ because something on 4AD – or Factory come to that – always looked so special. It looked like something you wanted to own.

EMMA ANDERSON:

Yes, they were pieces of art.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

Were the Lush sleeves all Vaughan Oliver’s work?

EMMA ANDERSON:

Yeah, there was no collaboration with the band. You didn’t collaborate with Vaughan Oliver! It was fine to let him get on with it [Laughs]

JUSTIN LEWIS:

So did he design the sleeve not knowing what the record would sound like?

EMMA ANDERSON:

No, he was definitely inspired by the music because I remember that the scratches on the Scar sleeve were there because of the kind of raw abrasiveness in the guitar sounds. And then later, Spooky, which Robin Guthrie produced, was a much rounder, softer sound. And the sleeves reflect all that. Lovelife, Chris Bigg did that one (I don’t know if Vaughan liked Lovelife much).

JUSTIN LEWIS:

Looking back now, you and Miki did write certain songs together, but most of the songs are credited either to you or Miki as solo compositions. How did you get started as a songwriter?

EMMA ANDERSON:

When Meriel was in the band, we did a demo which we used solely to get gig at that time.. I wrote a song, Miki wrote a song, Meriel wrote a song, and I think the last one on the tape was ‘Sunbathing’ which was the only one that then made it on to a later Lush release.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

The Sweetness and Light EP, right?

EMMA ANDERSON:

Yeah, I remember when we were making that [1990], ‘Oh god, we need another B-side!’ [Laughs] So we went back to that demo tape, and since then, you know… Jenny Hval has covered it, it was used in a Canadian TV series a couple of years ago… Of the other songs on that first demo, Meriel’s was actually the best! After she left, I did start writing differently. I don’t really know what happened, but something clicked where I did start writing better melodies and structures. How and why, I don’t know.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

When you look at the back catalogue of Lush, do you have a favourite album, one that you’re most proud of?

EMMA ANDERSON:

I can tell you the one I’m least proud of is the last one [Lovelife, 1996]. I don’t like being negative about our work, really, but I don’t think that one’s stood the test of time as well as the others. I think it lost something in that whole [mindset] of ‘Let’s go back to basics and get rid of the effects pedals.’ And obviously that whole Britpop influence was going on at that time. The only track I can listen to really off that album is ‘Last Night’, but that had a completely different approach as I was into trip-hop at the time and it shows there. Steve Osborne, who worked with Paul Oakenfold, mixed it so it has more of the dance, trip-hop vibe. I do love the outro of that song, actually.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

Quite apart from the terrible tragedy that happened with the loss of Chris shortly afterwards, I wonder if one problem Lush faced after the shoegazing scene was you never seemed to be considered part of subsequent scenes, which always puts established bands at a slight disadvantage. Because the music press had this idea of what category everything should be in. And also because 4AD put out two singles on the same day (‘Hypocrite’ and ‘Desire Lines’ in 1994)…

EMMA ANDERSON:

Oh yeah, that wasn’t our idea.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

…which may have seemed like an inspired idea when they’d done it with Colourbox [‘The Official Colourbox World Cup Theme’ and ‘Baby I Love You So’, both released on the same day in 1986], but the indie world was entirely different back in the eighties.

EMMA ANDERSON:

That idea came from our American A&R man, Tim Carr, and 4AD ran with it; there was a feeling that we weren’t going to get into the top 40 anyway, so it was, ‘Let’s do something a bit weird and sabotage things’ – why?!! But we had been in the Top 40 (‘For Love’, January 1992) but it charted quite low, and while ‘For Love’’s a great song, it was released on 30 December [1991], and it was a very quiet week.

But the other thing [by ‘94] was that almost everyone in the industry around the band was so obsessed with the idea of breaking America.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

Did you have a profile in America particularly? I know you had records coming out there, and ‘De-Luxe’ had got on the alternative rock radio playlists over there. Maybe it’s my age, but I feel very tired when I read about bands touring America for months on end for not particularly enthusiastic audiences.

EMMA ANDERSON:

We were signed to 4AD for the world and they had a licensing deal with Warners/Reprise. It was great that Warners were behind us there, and we toured a lot, and did things like Lollapalooza which, actually, I really loved. I had a great time. But, alas, I do think America took its toll on the band mentally and physically. Having said that, the audiences were actually very enthusiastic and we did build up a very good fanbase there, which exists to this day. But we didn’t sell a million albums, much to the disappointment of management/labels etc.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

I was quite surprised to find out quite how much touring in America you did.

EMMA ANDERSON:

Part of the problem, I think, was the band members had different ways of approaching this. We all enjoyed different aspects of touring (and to be honest of the whole business and being in a band anyway). I personally wasn’t particularly into these long tours and endless weeks away from home. One tour was OK but then not long after came number two and then number three. Miki had spent a lot of time in America, her mother lived there, so she was much more used to being in the US. I think Phil quite liked it; he had never been to America before being in Lush. I didn’t hate it but, I have to be honest, it was gruelling. On the last album, we were doing this tour of shows put on by local radio stations, all these gigs where the punters got in for free. They were throwing bottles and shoes at the stage and when I told management that morale in the band was low, they said, ‘You’re only here so we can get the radio station to play your record.’ But you’re just thinking, ‘Is this really why I wanted to do music?’

JUSTIN LEWIS:

You were doing a lot of TV back in the UK, round about Lovelife time. Is it true you did Live and Kicking one Saturday morning?

EMMA ANDERSON:

That was one of the better ones! We had a very good TV plugger, the late Scott Piering. We did Top of the Pops [for both ‘Single Girl’ and ‘Ladykillers’] … Big Breakfast with Zig and Zag, twice. This Morning with Richard and Judy, we went up to Liverpool to do that. Then there was Pyjama Party [co-hosted by Katie Puckrik and a young Claudia Winkleman], Hotel Babylon with Dani Behr, Dear Davina… We did some quite trashy stuff around the Lovelife time.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

I’m surprised I don’t remember seeing you on these, I used to watch quite a lot of night-time TV back then.

EMMA ANDERSON:

We did All Rise for Julian Clary [courtroom mock-up variety show for BBC2]… him and Captain Peacock [Frank Thornton] from Are You Being Served? That was Phil’s moment of ‘How low can we get with this?’, that show. So embarrassing.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

In what capacity were you doing that?

EMMA ANDERSON:

Basically, there was this young girl – about 12 years old. She’d collected a load of NMEs, a few hundred probably, and somebody had chucked them out by mistake. She was so upset that either she or somebody else wrote to this programme who obviously then contacted the NME who got together all these [replacement issues]… And our role was to come on and present this girl with all these NMEs. That was it.

—–

LAST: TAYLOR SWIFT: ‘The Fate of Ophelia’ (2025, single, Republic Records)

JUSTIN LEWIS:

You mentioned this as something you wanted to bring up.

EMMA ANDERSON:

I’m going to make a massive admission here: I don’t really consume a lot of new music. My finger is not on the pulse of new releases. But this obviously came to my attention because you can’t really get away from it. I don’t really have an opinion on Taylor Swift – I never understood why she was so massive, but I’ve also been intrigued by why she’s so massive. But I do think this single is alarmingly good. I cannot get it out of my head. I go to bed singing it, and I wake up singing it. The video is amazing, and then of course on Instagram when you look at one thing – in this case ‘the dance’ – the algorithm sends you all these clips, so I’ve now watched about fifty different people all doing ‘the dance’. And I’ve realised this really is quite a phenomenon.

So then I looked into the background of it, because I’m always interested in the production side, and it’s Max Martin and Shellback who’ve both worked with Britney Spears amongst others. And then, I started breaking down the actual song in my head. So there’s a chorus, but then as I said to my daughter, ‘It’s like there’s a post-chorus.’ And she said, ‘Of course there’s a post-chorus.’ My daughter’s been getting into K-Pop and that’s got post-choruses. I thought I knew about pre-choruses. But then I realised, actually, that there’s a song I’ve got on my Pearlies album called ‘The Presence’ and that’s got a post-chorus on it!

So I think I brought this Taylor Swift song up because it’s just made my brain ticking about lots of things. It’s quite fascinating, and so I am starting to understand why she’s so massive.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

There’s another thing I was going to say about Taylor Swift which I find a bit off-putting. With her previous album, two hours after that ‘dropped’, there was another album that came out immediately.

EMMA ANDERSON:

Oh, I was vaguely aware of that, yes.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

So what they said this time was: With the new album, no extra songs after it comes out, this is the album – only to then bring out lots of limited edition formats, each with one extra alternative version and demo of the existing songs on the album, which technically means there were no new extra songs, but it did mean that all the fans felt obliged to shell out for all these extra formats – and especially given her fans are often really young… I find it all a bit cynical.

EMMA ANDERSON:

Yeah, as much as I think aspects of her are great… that whole re-recording her back catalogue. You can slag off your original record company, but they put the work in in the early period. Is that taken into account? Without the work they put in, would you be able to do this now? But I get the idea that the fact they own your material is obviously quite an anathema to a lot of people, especially if you become huge (as she has done).

—–

JUSTIN LEWIS:

I wanted to ask you about Sing-Sing, the duo you formed after Lush broke up. Was this a way of trying to do something totally different from Lush?

EMMA ANDERSON:

After Chris’s death [Oct 1996], that whole year was just… awful. Even before Chris died, it’s not a secret, I wanted to leave the band. My way of coping after, in a way, was carrying on, and quite quickly start writing some more songs. But at that stage, I didn’t have a singer and I didn’t think I could sing.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

I mean, obviously, you were singing on the original Lush records.

EMMA ANDERSON:

Backing vocals, yes, which is completely different from doing lead which I had never really done at all. In fact, around 1997 I did some demos which 4AD paid for as they were interested in hearing new material and Pete Bartlett – our soundman who’d produced Lovelife – produced them in his flat. I gave them to [4AD founder] Ivo, and he said to me [laughs], ‘You can’t sing, Emma’. (Looking back, though, this is funny because Ivo actually really loves Pearlies, my solo album, and he absolutely thinks I can sing now. This actually means a lot to me as I have really obviously always valued his judgement.) Anyway, then myself and the remaining Lush members got dropped so I went looking for other singers. I found Lisa [O’Neill] via a couple of ways. She worked at an animation company called Bermuda Shorts with a really old friend of mine, Bunny, who I knew from school, but she also went out a guy who shared a flat in Camden with a guy that I was going out with. PLUS she’d also sung on the hidden track on a record by Mark Van Hoen’s project, Locust, an excellent album called Morning Light (1997). PLUS another connection: my friend Polly worked at a PR company called Savage and Best – they did Pulp, Elastica, Curve etc. John Best gave me a promo cassette of Morning Light. So, I thought, ‘Maybe this is meant to be’ – and we started working together.

The other thing about Mark Van Hoen was that he was an electronic musician and a whizz-kid programmer. After being in a traditional band set-up with a drummer and a bass player etc, for me, that was so refreshing. All the records I had made before, everything recorded had been recorded on to tape but this way you could just sit around the computer and it was BANG – it all got done very quickly and smoothly. But I still wrote songs in exactly the same way, and Lisa wrote songs too.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

Did you write together in Sing-Sing, or were these songs separately written compositions?

EMMA ANDERSON:

It was slightly different. Lisa couldn’t play an instrument, so she’d come up with melodies. Sometimes I’d flesh them out a bit, eg ‘I’ll Be’, and sometimes Mark would put chords to her melodies. But they were still her songs, and obviously her lyrics. But the whole process was just so different because it was of the computer-centric process. I’d never really done it like that before, and Mark’s such a excellent programmer. There were a few samples on the record, which were a nightmare to clear, legally [laughs]. But just watching him do it all was amazing, because he’d just pull out a record and say, ‘This would make a good drum sample’. And it would fit perfectly! It was a real eyeopener, and I enjoyed it immensely.

But then the problems weren’t about making the records, it was about getting them out there. I wasn’t on 4AD anymore…

JUSTIN LEWIS:

What was it released on in the end?

EMMA ANDERSON:

‘Feels Like Summer’ [the first version, 1998] came out on Bella Union but that was never going to be a permanent label. After that we actually became signed by Sanctuary and made the album with them but there were internal shenanigans and we got dropped and we were able to take the album with us, so I went to Alan McGee, who’d just started Poptones [his label founded after the end of Creation Records]. I knew Alan because I’d worked for Jeff Barrett (who owns Heavenly Records now but had been a PR) in the late 80s which was in the Creation Offices at Clerkenwell. And Alan said ‘yes’.

It’s funny now, because Lush are really celebrated – there’s all these reissues – and everyone loves shoegazing, and Slowdive and Ride and My Bloody Valentine. But in the late 90s, Lush were not seen as a particularly cool band. I was in my thirties when I was doing Sing-Sing and it’s hard to believe this now this, but ‘older’ women in music weren’t particularly respected back then. Now you’ve got PJ Harvey, and Björk, and Alison Goldfrapp, Kim Deal, all in their fifties, early sixties, you know? And it’s fine. But back then, people would literally say to me, ‘Emma, you’re over thirty, no-one’s interested’, even though the music was good, it was really good. But I think it didn’t really fit in with the early noughties time, The Strokes and The Gossip and Kaiser Chiefs and all that.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

Not really my thing either, that. I had just turned thirty, in 2000, and I find that period of guitar music in the early noughties even harder to listen to than Britpop. I mean, I like some Britpop – I was suspicious of the tag, but most of the bands made at least one record I liked. But I find the noughties a very strange period to revisit now. I wanted to listen to something else. But the other thing about this period – you got a ‘proper job’ as it were, right?

EMMA ANDERSON:

I’d worked before Lush, As I said, I worked for Jeff for a while, and after that then obviously Lush was my job. But by 2000 I had to go back into the world of day jobs. My first job was working for Duran Duran, I was their PA, 2000–02 and it was when the line-up was Nick, Simon and Warren Cucurrullo. Now obviously they’re back with John and Roger and they’re playing arenas, but when I worked with them wasn’t their most memorable period, although the album I worked on at the time, Pop Trash, was actually pretty decent. The single that came off that, ‘Someone Else, Not Me’, was really good. So I did that for a couple of years, and Sing-Sing were going at the same time. Then I worked as a management assistant at the company that managed Goldfrapp, Ladytron and a band called The Shortwave Set. I did that for two or three years, and then worked for the PR company Hall or Nothing who did Oasis and the Manics, as office manager. After that I moved to Brighton and got a job at 13 Artists, which is the booking agency for Arctic Monkeys, Suede and Radiohead amongst others.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

One thing I often think about, with being in a band: there must come a point when you start thinking, ‘Where are we today?’ You know your role is to do a gig and then travel to the next gig, but when you have an ‘ordinary’ job, you at least have a sense of place.

EMMA ANDERSON:

There’s a lot to be said for actually living a relatively normal life, you know?! Not knocking being in a band, but the weird thing is, Justin, I was only actually in Lush for about eight years. I’m fifty-eight but people associate me solely with being in Lush though it took up a relatively small portion of my working life. I’ve actually been an office worker way longer than I was a professional musician! It’s true!

JUSTIN LEWIS:

I’ve got a quote, which I’m going to read back to you, and you said this in 1992, so I appreciate you might think differently now, but I’ll mention it because it ties in with what you just said. To Simon Reynolds, in The Observer newspaper: ‘It’s weird to hear people talking about us as pop stars. When we were young, I used to be mesmerised by them, and even now I think we still can’t help seeing ourselves as part of the audience.’

EMMA ANDERSON:

Even now sometimes people say to me, ‘You’re a pop star’ and I baulk at it to be honest… I suppose I consider pop stars to be Prince or Beyoncé or Taylor Swift. I do remember that quote, and I was a little criticised for saying it, actually, I seem to remember.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

There’s a lot of sense in it.

EMMA ANDERSON:

There was that whole Madchester thing at the time… there was a lot of swagger going around.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

‘We’re the best band in the world’ type of thing.

EMMA ANDERSON:

Yes. And journalists kind of liked that. Of course they did. To me, being in a band was just something I did. I was never particularly ambitious. I always felt that I just picked up a guitar, wrote some songs, got signed, and we toured, we were able to do that.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

With your solo album, Pearlies, which I can’t quite believe already came out two years ago: I gather some of these songs date back to the Lush reunion from about a decade ago.

EMMA ANDERSON:

I had one or two songs, and some bits left over from the reunion (as I thought we were going to make an album. Or three). But that’s how I write anyway, in bits and pieces and I assemble them into whole songs sometimes. And I thought, I’d quite like to carry on. Originally, I thought I’d find another singer, again, like I had done with Sing-Sing. I did some demos with Audrey Riley [great cellist, many credits], and we did three tracks, but even with that, I said, ‘I’m not singing’, and she said, ‘Emma, you can sing! Just do it!’ She got in one of her students, a Norwegian girl called Anna, who sang the songs very beautifully, but I didn’t end up doing much with those demos. And then when I spoke with Robin Guthrie about doing some more demos, he said, ‘I will only do them if you sing. Forget it otherwise’ And that made me think, ‘Maybe I should do this.’

Then COVID happened, and Robin lives in France… but I realised there’d been all these people telling me I couldn’t sing all that time. Even when I was at school, I was quite into music, I did like singing, and there was a choir which I so wanted to get into. Every term I auditioned for it, and he’d say, ‘I’ll put you on the reserve list’ – as he felt a bit sorry for me.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

I’m really glad you did do it for Pearlies. Because it’s all about having personality in your voice anyway.

EMMA ANDERSON:

I don’t think it’s just about the voice, though. The thought of standing at the front of the stage in the middle, being the focus, petrified me [laughs].

JUSTIN LEWIS:

Oh I can understand that.

EMMA ANDERSON:

I don’t have that personality. I don’t really enjoy being the centre of attention. I was perfectly happy being at the side with Lush and Sing-Sing – in fact, I found it preferable.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

Thinking about it, when you see a band on TV, the camera tends to focus on the singer, they only cut away to someone else when the singer isn’t singing. You haven’t been touring the record, but I know there are good reasons for that.

EMMA ANDERSON:

The main reason is that I’m a single mother of a school-age child so going on tour is – well, nigh on impossible. I also work (I am a bookkeeper) and there are some financial constraints to touring too, especially as I am a solo musician now.

Some people have suggested, ‘Oh, just do it with you and a laptop.’ But I don’t want to do it like that, I’d want a proper band – and if it was just me and a laptop and a guitar, and it was a bit rubbish, you get people filming things and putting them on YouTube. So there’s an element of caution with it as well.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

Speaking of YouTube, I note that the Lush film, Lush: A Far From Home Movie – which was quite hard to see here, but was on the Criterion streaming site in America – is on YouTube now.

EMMA ANDERSON:

It’s Phil’s film, and we did some live showings of it. It was great, actually. It’s a sweet film.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

It’s nice and prescient that someone thought to capture that footage at the time. We’re used to doing that now on a camera or phone, but in the 90s, people weren’t thinking like that so much. So even to just have some bits filmed, you weren’t necessarily going to do anything with them.

EMMA ANDERSON:

Yeah, Phil had a Super-8 camera, so black and white, no audio. You could only film literally a few minutes at a time. So it’s very evocative. Even though it was filmed in the 90s, because of the quality it looks like it could have been filmed in the 50s. And there’s lots of Chris in it as he was so good in front of the camera.

—–

ANYTHING: GAVIN BRYARS: ‘Jesus’ Blood Never Failed Me Yet’ (1975, Obscure/Island Records)

JUSTIN LEWIS:

I always have to take a deep breath before listening to this because I find it so overwhelming.

EMMA ANDERSON:

In a way, I chose it because you asked for something that made you think about music differently. I did my degree at what was then Ealing College of Higher Education but it is now, after many name changes, the University of West London. The degree was called Humanities – you did six subjects in the first year, and then you majored in one and minored in two. My major subject was History of Art but one of the minor ones was Music, and there was a teacher and lecturer there called Allan Moore, who’s a musicologist. He used to play us things like Karlheinz Stockhausen’s Stimmung, and also this by Gavin Bryars. I just remember sitting in this lecture room, in this college, and him putting this on, and being completely transfixed, as in ‘What am I listening to here?’ This obviously old recording, of this old guy singing, outside, looped over and over, with these strings that built and built… It’s a very emotional experience.

But it’s quite important to me that I actually heard this at college, rather than on the telly or at a mate’s house. And I’ve got the record now.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

Which version is this, because there are several?

EMMA ANDERSON:

The other side is ‘The Sinking of the Titanic’.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

Ah, the original record, that came out in the 70s.

EMMA ANDERSON:

And I noticed, when I knew I was going to do this interview, that Tom Waits has also appeared on a recording. Which makes total sense. And Audrey Riley who I mentioned earlier – she’s played with Gavin Bryars as well, she knows him quite well. So I’m not an afficionado of modern classical music or whatever, but this has meant a lot to me and made me see things in a different way. And it was interesting working in Lush with Audrey on string arrangements… I mean, when I was a child, I really wanted to learn music, the piano specifically. I begged and begged to have piano lessons, but I wasn’t allowed, basically. So I do sometimes wonder, had I had piano lessons and got into that world, my life might have been a bit different.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

That’s a real shame you never got that opportunity then. Is ‘Jesus’ Blood’ classical music or not, then, I wonder? Because it lies somewhere between lots of things. I have a feeling I first heard this in the early 1990s, because incredibly, this was on the Mercury Prize nominations list [the 1993 list, and a three-minute edit of the Tom Waits recording which you mentioned was included on a Mercury sampler album alongside PJ Harvey, Suede, Apache Indian and the Stereo MCs]. They used to put out a sampler every year of the Mercury nominations, not sure they do this anymore, but at the end there’d always be the token classical record, which would never win, and you wish it would sometimes.

But the thing about an extract of something like this – it doesn’t really work. You have to have the whole thing. [EA agrees] Because it takes about five minutes for the strings even to start.

EMMA ANDERSON:

It’s very gradual which adds to the emotional weight of it.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

And then the effect of having the strings start to drown out the man’s voice – and at times, you only hear the man’s voice whenever the strings pause, before starting again. I have to ration it because it’s one of those pieces I wouldn’t want to get too used to. It’s a record that’ll stay with me for ever.

This is the kind of record I was thinking of, with wildcard choices for this textcast. I couldn’t get my head round repetition when I was very young, and what shook me out of that was firstly modern classical music, and then also dance music. Because that was also about minimalism and loops. I suddenly realised I’d have to listen to music differently. Because I was 17, 18 when acid house came in.

EMMA ANDERSON:

I was actually really into dance music – I used to go clubbing quite a lot in the late 80s/early 90s and I’ve got a few records from that period.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

What would be an example of an acid house ‘anthem’ that would evoke that time for you?

EMMA ANDERSON:

‘Strings of Life’ by Rhythm is Rhythm… I loved that. ‘The Real Life’ by Corporation of One, which has got samples from Simple Minds’ ‘Theme from Great Cities’ and then it cuts in with Queen’s ‘Bohemian Rhapsody’. What else? ‘Where Love Lives’ by Alison Limerick was always a favourite. ‘Sweet Harmony’ by Liquid. Sometimes I’d hear things at the time but wouldn’t know what they were. But I was quite into this stuff, because I worked for Jeff and there was that whole club scene… I went to the Hacienda a few times, Shoom, Milk Bar with Danny Rampling…

I expect people maybe assume I must only be into My Bloody Valentine and Cocteau Twins… but I’ve got quite a broad taste (I like to think so anyway!).

—-

Lush’s Gala compilation was reissued on 4AD on 14 November 2025, marking its 35th anniversary, and completing the label’s reissues of the group’s back catalogue. More information here: https://4ad.com/news/22/9/2025/35thanniversaryeditionofgala

Phil King’s film, Lush: A Far from Home Movie, can now be seen in full on 4AD’s YouTube channel: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ow3jEIV0s74&list=RDow3jEIV0s74&start_radio=1

Emma Anderson’s 2023 solo album Pearlies is out on Sonic Cathedral Records, as is its 2024 remixed version Spiralée (Pearlies Rearranged). Further information at her Bandcamp page: https://emmaanderson.bandcamp.com/music

You can follow Emma on Bluesky at @emmaandersonmusic.bsky.social, and on Instagram and Facebook at @emmaandersonmusic.

—–

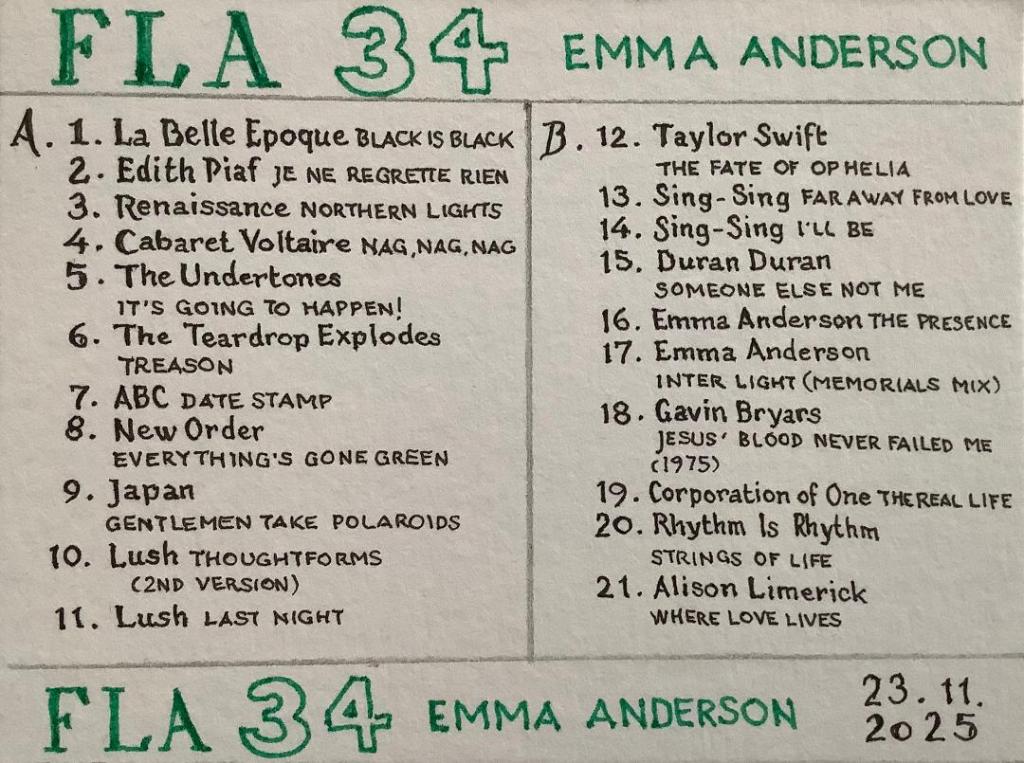

FLA Playlist 34

Emma Anderson

(For the time being, this site and project uses Spotify for the conversation playlists, but obviously I disapprove that Spotify doesn’t pay artists and composers properly, and other streaming platforms are available, as are sites to buy downloads and buy recordings. For consistency, you can also listen to the selections via YouTube (where available), and links are provided in each case, below.)

Thanks to Tune My Music, you can also transfer this playlist to the platform or site of your choice by using this link: https://www.tunemymusic.com/share/4z65FUBy0X

Track 1:

LA BELLE EPOQUE: ‘Black is Black’:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=v3nf4UsEdlA&list=RDv3nf4UsEdlA&start_radio=1

Track 2:

EDITH PIAF: ‘Je ne regrette rien’:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4r454dad7tc&list=RD4r454dad7tc&start_radio=1

Track 3:

RENAISSANCE: ‘Northern Lights’:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HKBJqHvQvjg&list=RDHKBJqHvQvjg&start_radio=1

Track 4:

CABARET VOLTAIRE: ‘Nag, Nag, Nag’:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pWGZWYrR5Nw&list=RDpWGZWYrR5Nw&start_radio=1

Track 5:

THE UNDERTONES: ‘It’s Going to Happen!’:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=aQtaqgW6MXg&list=RDaQtaqgW6MXg&start_radio=1

Track 6:

THE TEARDROP EXPLODES: ‘Treason’:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rV8cEIsFX-A&list=RDrV8cEIsFX-A&start_radio=1

Track 7:

ABC: ‘Date Stamp’:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=434lTbIZsJ0&list=RD434lTbIZsJ0&start_radio=1

Track 8:

NEW ORDER: ‘Everything’s Gone Green’:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4v5ivB7bM1k&list=RD4v5ivB7bM1k&start_radio=1

Track 9:

JAPAN: ‘Gentlemen Take Polaroids’:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SlyI2isjAas&list=RDSlyI2isjAas&start_radio=1

Track 10:

LUSH: ‘Thoughtforms’ (2nd version):

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gWYXR78pf7k&list=RDgWYXR78pf7k&start_radio=1

Track 11:

LUSH: ‘Last Night’:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bHngGUzLkD4&list=RDbHngGUzLkD4&start_radio=1

Track 12:

TAYLOR SWIFT: ‘The Fate of Ophelia’:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ko70cExuzZM&list=RDko70cExuzZM&start_radio=1

Track 13:

SING-SING: ‘Far Away from Love’:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_cuOr2TCcQw&list=RD_cuOr2TCcQw&start_radio=1

Track 14:

SING-SING: ‘I’ll Be’:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rLhsWXlCmUo&list=RDrLhsWXlCmUo&start_radio=1

Track 15:

DURAN DURAN: ‘Someone Else Not Me’:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RyThuzD1vUo&list=RDRyThuzD1vUo&start_radio=1

Track 16:

EMMA ANDERSON: ‘The Presence’:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rCyo6Dq6Dvg&list=RDrCyo6Dq6Dvg&start_radio=1

Track 17:

EMMA ANDERSON: ‘Inter Light’ (MEMORIALS Mix):

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=x3At7nRpepY&list=RDx3At7nRpepY&start_radio=1

Track 18:

GAVIN BRYARS: ‘Jesus’ Blood Never Failed Me Yet’ [1975 original]:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rfJXXOFLzfQ&list=RDrfJXXOFLzfQ&start_radio=1&t=82s

Track 19:

CORPORATION OF ONE: ‘The Real Life’:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9AEp9-BOGOw&list=RD9AEp9-BOGOw&start_radio=1

Track 20:

RHYTHM IS RHYTHM: ‘Strings of Life’:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vGFw2qeUp0s&list=RDvGFw2qeUp0s&start_radio=1

Track 21:

ALISON LIMERICK: ‘Where Love Lives’:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wGYdeSnux68&list=RDwGYdeSnux68&start_radio=1

Maybe because it’s felt like the 24-hour news media has been laughing at us for months, but I’ve started to be plagued by the memory of a most disturbing record.

Maybe because it’s felt like the 24-hour news media has been laughing at us for months, but I’ve started to be plagued by the memory of a most disturbing record.