Picture (c) Monika Tomiczek

Since the day I started reading the author, broadcaster and musician Dr Leah Broad’s magnificent Quartet: How Four Women Challenged the Musical World in the early spring of 2023, I knew I wanted to talk to her for First Last Anything.

Quartet is an accessible, thoughtful biography of four of England’s foremost women composers. It has won several book awards (including a Presto Music Books of the Year Award in 2023, and the Royal Philharmonic Society Book Award in 2024), and has led to a series of concert events of talk and music called Lost Voices, in which the composers’ works were brought to life by Leah, the violinist Fenella Humphreys (who was the guest for FLA episode 5 in July 2022) and the pianist Nicky Eimer.

With their overlapping lifespans covering a total of nearly 150 years, the four composers that Leah focused on for Quartet are Ethel Smyth (1858–1944), Rebecca Clarke (1886–1979), Dorothy Howell (1898–1982) and Doreen Carwithen (1922–2003). In our conversation, on Zoom one afternoon in August 2025, Leah explains why she chose these four women for the book, but we also talk about much besides – including the representation of women composers in educational syllabuses, at the 2025 BBC Proms, and for her forthcoming book project: women in music during World War II. Plus find out Leah’s first, last and wildcard music purchases. Leah was so generous with her knowledge, experience, expertise and time, and I found it all absolutely fascinating. I’m sure you will too.

——

JUSTIN LEWIS:

The first question is one I ask everybody. What music do you first remember being played in your home when you were growing up?

LEAH BROAD:

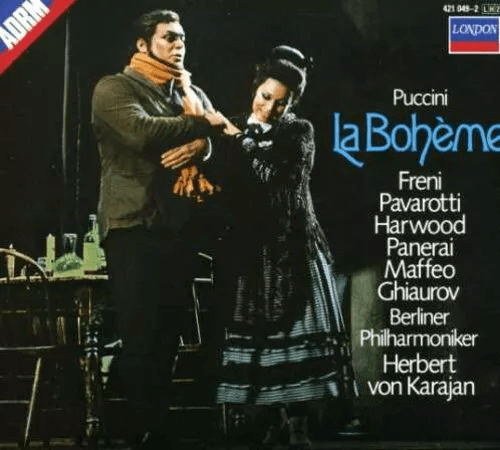

Oh, it was a highlights record. It was Highlights from [Puccini’s] La Boheme, on vinyl, with Pavarotti singing. I used to play this whenever there was a storm because I was really afraid of the storms, and so this was just really calming. My parents listened to mostly Kate Bush, Genesis, The The, and then they had some popular classics albums especially because my grandfather really loved classical music and so we got some of his vinyl as well.

So that’s what I remember, along with Kate Bush’s Lionheart, which my mum had. I guess when I grew up, there was nothing unusual about classical music. My family weren’t musicians. My dad had played drums before I was born, but nobody played an instrument while I was growing up. There was nothing classical musical background-wise there whatsoever, but it was just part of the music that I chose to listen to when I was little.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

It’s interesting that you have the pop and the classical in your life at the same time.

LEAH BROAD:

Yeah, my dad had once wanted to be a drummer, and so he had played professionally for a little while. So he was heavily into drumming before I was born. By the time I came along he was an estate agent for a while, and then he set up his own business, was small shop owner, but he still loved prog-rock. My mum was the biggest Kate Bush stan on the planet and for some reason I liked classical music – so I don’t know what happened there.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

Do you still keep up with pop as well as classical? Are you still into both?

LEAH BROAD:

Oh, do I!

JUSTIN LEWIS:

I presume it doesn’t feel like a big gap between the two.

LEAH BROAD:

To me, in terms of what I listen to, it just feels like I listen to music that I enjoy and I am quite happy seguing from like, Janelle Monáe to… Avril Coleridge-Taylor. Just what I happen to be listening to. In terms of cultures that surround this music, though, there are vast differences between the two. Classical music feels like it’s going through a period of change in terms of who both listeners and performers are. Very often you find out that for younger performers and younger listeners, there is no massive bridge between pop and classical. We all grew up like this, right? Pop, and classical, and everything else combined.

But particularly in the way that classical music is written about… the things that are written about female performers, by example, by classical music reviewers, are jaw-dropping compared to pop criticism. The type of language we see used about somebody like Yuja Wang [astonishing Chinese-born American piano virtuoso], for example. So much is written, derogatorily, about her short skirts and tight outfits. And I’m like, ‘Get your ass to a Taylor Swift concert and learn!’ It’s unacceptable.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

Are we talking about Norman Lebrecht here, by any chance?

LEAH BROAD:

It’s not just him. It is widespread, this sort of entrenched idea that classical music is special, and it shouldn’t be defiled by “slutty women”. It’s quite alienating. The idea that you’re disgracing yourself and the music if you wear a slightly short skirt, is just not something you’d see written by pop critics. There does feel like there’s a divide in the way the music is being thought about. Because narratives about reverence that come with classical music are just not present in pop.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

I’m about to have a new book published about a history of the 1980s in pop music [Into the Groove, out in October 2025] and one reason I wanted to do that is to try and reassess that decade in terms of the greater inclusivity we have now. And it’s really surprising quite how male it was. These were my formative years, so I didn’t really think about it too carefully at the time, but it’s as if the industry was, ‘We’ve got Kate Bush, we don’t need another’. Maybe Annie Lennox, both of whom absolutely brilliant, obviously. And funnily enough, the arrival of Madonna – I was just thinking then when you mentioned Yuja Wang – it became all about what she was wearing. After which there was this explosion of creative women pop stars.

LEAH BROAD:

Right. And it feels like classical music is almost having that moment now. Forty odd years later, right? We need our Madonna — maybe we’ve got her in the shape of Yuja Wang. And there are so many performers now who say, I’m going to wear whatever I want to wear. And also a more widespread understanding that women aren’t these alien creatures that are included only because you have to, because they’re singers. They’re an integral part of the fabric of classical music. But yeah, it feels like we’re having that realisation and it takes a long time for attitudes to change.

I really want to read your book, by the way, because this transition period just absolutely fascinates me. Talking about formative periods… I was born in 1991, and I was growing up with the Spice Girls. I remember them as pioneering feminists – and I look back now… I saw this interview with Victoria Beckham the other day. She was so painfully thin and had these issues around body image and eating and weight. And this interviewer asks, ‘Have you lost the weight you’re intending to? Have you lost the weight you wanted to?’ And she says, ‘Oh yes’, and then he gets out a pair of scales and goes, ‘Go on then – get on the scales and prove to me you’ve lost the weight.’ What?! We grew up with this! This was on TV, this was just the way that women and their bodies were treated. And here was one of the women I remember as being a powerful woman of the 90s being treated so disgracefully…

JUSTIN LEWIS:

I think the Spice Girls came along at a point when Britpop had been pretty male, there weren’t many women in Britpop, really. But the number of younger women I know who have all said, ‘Yes, I was a massive Spice Girls fan’ partly because visibility in itself was so important.

LEAH BROAD:

I was six or seven when the Spice Girls were coming out. We’d all sit in our little group listening to the new Spice Girls record, saying ‘Oh my god, they’re so good’, but it was really because they were the only people we saw in pop like that, and they were very unapologetic for who they were as well. I think that was really powerful for young women growing up. But now, there’s a flip side of realising that there were all these other narratives surrounding them that I don’t remember quite as well, but obviously will have been assimilating at the same time really problematic ideas about the way women are being treated and presented. We still have criticism talking about opera singers’ body weight and this kind of nonsense — in ten or fifteen years, we’ll look back on it and think, ‘That’s disgraceful.’

JUSTIN LEWIS:

When I was reading Quartet, even vaguely knowing that awful things had been written about women in music over the years, it was still quite astonishing to see them in print like that. But during the research for my book, I discovered two incredible things: the first solo female rapper to have an album of her own released was MC Lyte as late as 1988, and that the first ever female head of a major record company in Britain was Lisa Anderson at RCA and that was as late as 1989. So to look at the 80s through that prism, seeing how it was mostly men who were making those decisions about marketing. Even now, I can’t think of many women record producers who aren’t producing their own stuff. Are there many staff producers who are women? It’s very difficult to think of them.

LEAH BROAD:

There are statistics on this. The 2024 Misogyny in Music report found that record production is still one of the most male-dominated areas of the industry, as are the more techie kind of jobs as well. It’s still a big problem.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

An album I was going to mention when you were talking about younger performers is Women by the violinist Esther Abrami – which came out this year.

LEAH BROAD:

I nearly mentioned her just then, yeah! Because she just did an Instagram post about comments she gets about wearing skirts that were too short.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

I did see that! That album is programmed in a refreshing way, it’s got a wide range of music, but it’s sequenced in such a way that it flows, there aren’t really gaps between the tracks, it has this pace to it, even though it has many different styles and moods.

LEAH BROAD:

A little like a concept album.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

Yes, and in fact it starts with ‘March of the Women’, composed by Ethel Smyth – who we’ll come to shortly – and it ends with a piece Abrami composed herself (‘Transmission’) and there’s an arrangement of ‘Flowers’, the Miley Cyrus song, and arrangements of work by film composers such as Anne Dudley and Rachel Portman, but also selections from women composers whose names were new to me [including Irene Delgado-Jiménez and Chiquinha Gonzaga].

This must be a very exciting period – perhaps frustrating at times – for you as a historian because there’s all this untapped material about women composers, that almost nobody knows about.

LEAH BROAD:

It’s incredibly exciting. Overwhelming sometimes, but incredibly exciting. There’s still a widespread lack of knowledge, and it’s surprising because there have been feminist musicologists around since the 60s, 70s, 80s, 90s… They did the groundwork, and I couldn’t do my work if they hadn’t been around preserving things, especially by 20th century composers who would otherwise have completely fallen off the radar. But prejudice — or ignorance — is still widespread. One question I get asked a lot is ‘Oh, but are there any good pieces by women?’ Or: ‘If they were good, wouldn’t I already know them?’ Or: ‘Oh my goodness, having read this book, I didn’t realise that women wrote music’. I think those thoughts are still there for so many reasons, but women are on the radar in a niche sub-section of classical music. But it can still feel quite surprising for some people that there are really good works by women.

Interestingly enough, I’ve experienced less surprise from literary readers that women write music, than from readers who think of themselves as classical music lovers. Classical music audiences can come with the belief, ‘Well I listen to a lot of classical music – therefore, if it was good, I’d have heard it already.’ Whereas literary audiences are more likely to say: ‘I don’t know much about classical music, but totally makes sense to me that women would have written music’. So it’s less surprising to them because they’re not coming with that backlog of knowledge.

Classical music readers are more likely to say: ‘What? What do you mean? There’s all this extra stuff I didn’t know about!’ So when you encounter new music by women I think you have to confront something, as a classical music listener, about prejudices in the industry, and admit the gaps in your own knowledge. That’s a really interesting difference in how readers have come to Quartet. They’ll often email me or come and talk to me after gigs. There’s a really marked different in terms of how surprised people are by women being composers.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

I started a music degree at university, in 1989, and I only did the first year – switched to English single honours after that – so it may be that I wasn’t fully paying attention, and I’m happy to acknowledge that could be a possibility! But I do not remember at any point in that year, and the same during A level, same in school orchestras, learning instruments… at no point ever in that period do I remember anyone mentioning a woman composer. And contrasting that with reading English at university – funny, given you just mentioned the literary world – where we were studying Jeanette Winterson or Alice Walker or Caryl Churchill, and it was quite a political course in many ways, obviously because we were doing a lot of contemporary study as well as the traditional canon.

But anyway. Nobody ever seemed to mention female composers then, and I was wondering if you, someone a lot younger than I am, did it occur to you that there didn’t seem to be any? Did that hit you quite early on?

LEAH BROAD:

No, no. I trained as a pianist, and I think the only piece by a woman I remember playing was by Pamela Wedgwood on the Grade V syllabus, a sort of jazz piece. The question: ‘Where are all the other women?’ didn’t really register. Because I did the Beethoven sonatas, I played Ravel, I was really into Debussy, these were the people I studied and you never saw women’s names on the lists of repertoire for all the big competitions. So I absorbed this narrative that the good composers were just men, and that’s just how it was.

At university, [studying music], there was an optional course on women composers. And I don’t want to say this, but it’s true: I did not take it because the general view was ‘Well the music on it isn’t very good but you have to know this stuff because it’s historically interesting about how women were treated.’ And I didn’t want people treating me differently because of my gender, I wanted to be taken seriously here. I think, as a teenage woman, I was very used to being sexualised all the time, growing up. I did not want my university experience to be marked by that, so I was not gonna take this course. I wanted to do the “serious” music that people respected. One of my dear, dear friends, a wonderful feminist, said, ‘Leah, you get on that course’, and we had a huge argument over it. I was like, ‘No, I do not want to be seen as a woman first and a thinker second – absolutely not. This is not for me.’

And then I was listening to BBC Radio 3 on my phone so I couldn’t see details about what was playing, and this piece of music came on, and I had to stop and find out who the hell wrote it. It was Rebecca Clarke, her Viola Sonata – and after that, I started looking up pretty much everything I could find by her. And it was really good! It did not fit what I’d been told about “women writing rubbish music but we study them because it’s politically important”.’ I was midway through my undergraduate degree by then, this was 2011, 2012, and I decided to start independently reading all this feminist literature about women and listening to the music. And luckily it coincided with this boom in recordings of women, and particularly more broadcasts of women on Radio 3, where they were incorporating women as Composer of the Week. So I could go through and listen to those.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

Yeah, it’s not just International Women’s Day with Radio 3, they seem to be committed all year round.

LEAH BROAD:

Exactly. Radio 3 have been really stellar. Right through the year, they programme an awful lot of music by women, they’ve been fantastic.

I’ve stopped teaching at university now – I write full-time – but I taught at Oxford for about ten years, and very often, when students came into my tutorials, it was the first time they would have encountered music by women, because I incorporated women in my courses, including in subjects that weren’t gender focused – like analysis, for example. And that felt just so disappointing, that you could still study music for so long and not have encountered women as composers. It’s especially disappointing for those women students who wanted to compose. Comparing when I started teaching, though, and when I ended, the students were so politically engaged that by the end of those ten years, they’d be coming to me and saying, ‘I want this on the syllabus’ and ‘Why aren’t you teaching THIS?’ So I have so much faith for the future. They know what’s what.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

So you were teaching undergraduates in this period?

LEAH BROAD:

Yes.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

I have a theory, which may not hold water, but I’ll say it anyway. Just after I did O level music, in the late 80s, they introduced the GCSE syllabus at school, and one of the new features of the GCSE syllabus was composition, which had never been part of the O level course at all. Do you think that the GCSE syllabus has enabled more young composers to emerge, simply because they’re encouraged to compose at an earlier stage?

LEAH BROAD:

Oh man. This is such a difficult topic because of all the defunding of music in schools. At the point where I left university teaching, the undergraduate entrance criteria were being changed so you didn’t have to have A level music, because so few state schools offered A level music that it would have been deeply exclusionary. So this is a problem that universities are having to deal with. A lot of people who would want to study music haven’t had the opportunity to study it at school – and so you can have these incredibly talented performers who somehow managed to learn music because they’ve had independent teaching, but would be excluded from university applications because their schools don’t offer A level music. And so in a sense, it’s immaterial what goes on to the GCSE syllabus if your school doesn’t have the resources to teach it.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

So that’s changed since, when, 2010? Was it better before that?

LEAH BROAD:

Well, music was not quite such a fringe subject as it’s now becoming in the UK. It’s deeply concerning.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

That’s just astonishing. I mean, clearly, I’ve not been paying the right kind of attention to that. But then I don’t have children, I don’t have that direct connection to education. When I was a teenager in the 80s, I was at a comprehensive in Swansea, quite a good one, we had a school orchestra, pretty good music department, so that was an option. But the idea you wouldn’t have those subjects anymore… education should fire the imagination a bit.

LEAH BROAD:

For classical music in particular, it takes money and time and resources to learn an instrument. Funding in schools is just so important, and being able to explore music, maybe try learning an instrument… that’s how most people get into loving music, through records, and trying out an instrument.

It’s really depressing, honestly… but in principle, having composition as part of the GCSE syllabus, as part of the A level syllabus is really important, and I’m really glad that the A level syllabus is changing as well to make sure there are musical examples by women. There was a campaign several years ago, by a student, her name was Jessy McCabe. She got women included on the A level syllabus, and it’s been increasing since then.

[In December 2015, McCabe’s campaign led to Pearson (who offer the Edexcel qualifications) altering its A level music specification to introduce five new set works by female composers: Clara Schumann, Rachel Portman, Kate Bush, Anoushka Shankar and Kaija Saariaho. McCabe’s campaign began when she noted that Edexcel’s list of 63 composers on its syllabus had not included a single woman.]

——

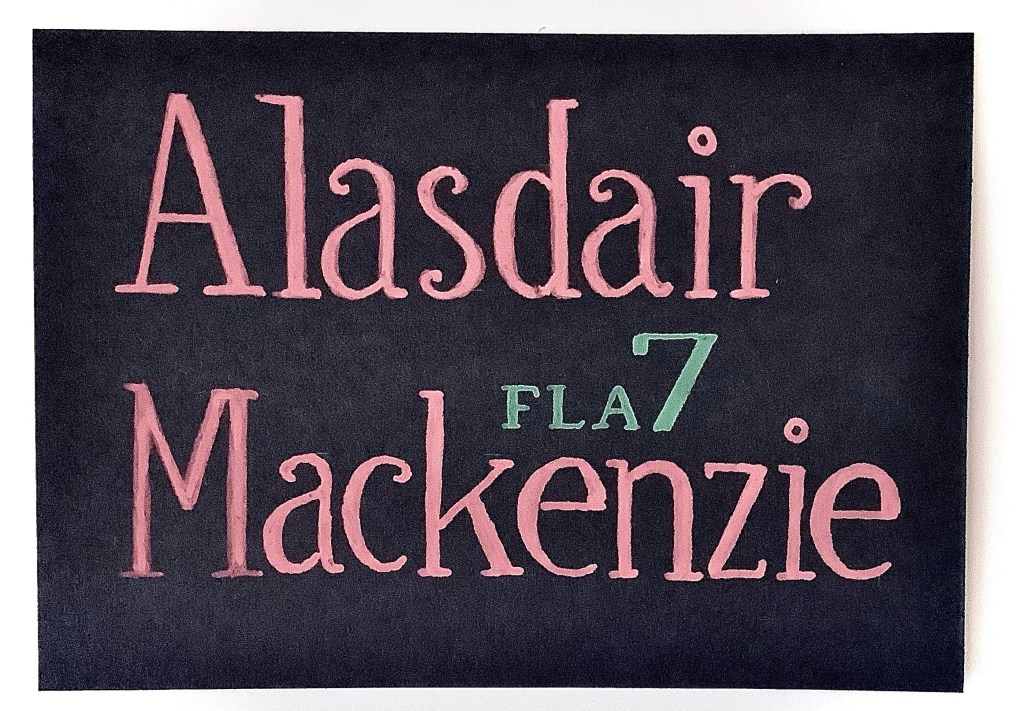

FIRST (1): VLADIMIR ASHKENAZY: Ludwig Van Beethoven – Favourite Piano Sonatas (Decca Records, double CD compilation, 1997)

Extract: Beethoven Piano Sonata No 17 in D Minor (‘Tempest’) – III. Allegretto

FIRST (2): AVRIL LAVIGNE: Let Go (Arista Records, album, 2002)

Extract: ‘Complicated’

JUSTIN LEWIS:

I didn’t think to ask you which Beethoven Piano Sonatas collection by Ashkenazy it was. There’s a box set which is about 9 hours long. But there’s also a selection.

LEAH BROAD:

It was a Decca double CD, all the big hit sonatas. So the Moonlight, the Appassionata, the Tempest, the Pathétique, the Pastoral, Waldstein and Les Adieux.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

And meanwhile you’ve got Avril Lavigne. Were both these albums around the same time? 2001, 2002?

LEAH BROAD:

Yeah, it must have been. I was about eleven. I had an Avril Lavigne phase, and I was going around with my arm-warmers and all my great big eye make up on, being like Avril Lavigne… and then turning up and playing the [Beethoven] Waldstein [Sonata No 21]! [Laughs] But that was me! I wanted to be a punk on weekdays and a classical musician on the weekends. And I didn’t really see any problem there, or discrepancy between those two. So yes – I was a piano-playing teenage goth.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

So what was it about Avril then?

LEAH BROAD:

The music first of all, I was so there for ‘Sk8er Boi’, I really loved that. And I wasn’t a girly girl, I was a bit of a tomboy – and so when she came out with this very grungy look, I was like, ‘That’s me with the baggy trousers and this great big black cardigan like on the front cover of the album.’ And I think she also had this slightly overwrought teenage angst that, frankly, I felt I could also explore in some of Beethoven’s piano sonatas!

JUSTIN LEWIS:

How interesting! These two sides inspiring the same sorts of reactions from you.

LEAH BROAD:

I just didn’t see any sort of barrier between the two, and so I was listening to both at the same time.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

Were you studying pop at school as part of the music course at all? Did you have to study a pop album?

LEAH BROAD:

I mean, it was pop music, but I think we did The Beatles and Jimi Hendrix. It wasn’t the stuff I was listening to. It was sort of like “worthy” pop that had been deemed appropriate for inclusion and ‘wouldn’t corrupt our youth now’ kind of vibe.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

Which Hendrix album was it?

LEAH BROAD:

I think it was just one song, ‘Little Wing’. Maybe this was just one song that my teacher liked. I don’t know whether it was actually on the syllabus. And then there was Sergeant Pepper – we did more songs from that, but… god, you’re testing my memory now! Syllabuses take so long to catch up, right? I mean, what would I have been listening to? Christina Aguilera’s Stripped (2002) – but I don’t see ‘Dirrty’ anywhere on the GCSE syllabus!

JUSTIN LEWIS:

That might be a while away, I think!

LEAH BROAD:

There is still a kind of divide between music you study in school and music you listen to… and this is why I really like university. Very often tutors will be teaching on their passion projects, so they’re teaching about the stuff they listen to and enjoy. So a lot of my colleagues teach about Billie Eilish or drag, so stuff that’s much more contemporary.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

Music has this thing of going in and out of fashion. We’ll talk about this more in relation to Quartet but one thing that blew my mind – something I’m sure you’ve known for years – was a couple of years ago, when Petroc Trelawny was still on Radio 3 Breakfast, he happened to say one morning about how JS Bach’s music had barely been played after his death [in 1750]… until Felix Mendelssohn revived it in about 1830.

LEAH BROAD:

Yes, Bach’s a bit of a 19th century phenomenon.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

And that’s when I realised that almost nothing can escape the risk of going out of fashion. It’s a bit different these days because of recordings, but… I think you mentioned in Quartet about how Beethoven and Schubert were perpetually popular, but it was unusual for composers to have that kind of afterlife.

LEAH BROAD:

But with caveats, right? Because there were Beethoven pieces that were very popular, but also there was the Beethoven that was thought of as densely intellectual. And if you were going to programme that, you needed to break it up with some sort of musical filler and some nice songs – because otherwise the audience are going to get bored and scared and not turn up.

So, yes, Beethoven has always been popular but it depends which bits, and which audience as well. And that’s why he was so important at the start of the 19th century. He was this very intellectual composer who wrote music that sounded a bit like noise at first — so he was patronised by the tastemakers who wanted to show how clever they were by patronising this composer who wrote densely intellectual music that very few people could understand. So yes, he was very popular within certain circles, but it’s music that you aspire to, rather than music that you just GET – unless it’s ‘Fur Elise’ or the first movement of the Moonlight, pieces that take on a separate life outside of these smaller classical music audiences.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

I was interested, re-reading Quartet, to realise that after you’d suggested the Beethoven Sonatas to discuss, to read that the sonatas were also an obsession for the teenage Ethel Smyth. And I saw another parallel, again maybe unwitting, about how Rebecca Clarke would present pre-concert lectures about what she would play, and how you’ve been doing something similar with the Lost Voices live events you’ve been doing.

LEAH BROAD:

I probably have brought out things like that a little bit, because in the experience of writing up the book, I would often be reading these composers’ materials, reading what was important to them, and for the first time be able to relate to them. I read about Dorothy Howell and Doreen Carwithen and their going to the Royal Academy of Music to study, writing about their pre-concert nerves… and I’d remember my own nerves going up there for my audition… and I felt terrified too.

I think I never really felt as though it was important to me, or even mattered to me, that composers’ experiences felt even a little bit relatable to me. I liked the oddness of the people I wrote my PhD about – Sibelius, Ture Rangström and Wilhelm Stenhammar. When I read about Sibelius’s life, I was fascinated by it intellectually. But with some of the women in Quartet, there was an emotional connection that I hadn’t experienced previously. And I wonder what we’re missing by reducing our histories so hugely. Maybe there are other experiences that other people want to relate to as well, and those books need to be written.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

In fact, didn’t you win the Anthony Burgess Prize for a Sibelius essay? In The Observer newspaper maybe a decade ago.

LEAH BROAD:

Yes, I wrote a piece about his theatre music. I like the stuff that other people think is inconsequential! My PhD – here’s a niche subject for you – was about Nordic incidental music. And that was great fun because it opened up this different lens of thinking about Nordic composers. In a lot of the classical music literature, they were written about as peripheral Nordic northerners, defined in relation to this central, Germanic canon. But I felt: ‘OK, but what if we stand in the Scandinavian countries and look out?’ And then you find that they were really quite happy… yes, there was this anxiety about their relationship to Germany and France… but especially in the theatre, there was this abundance of creativity and experimentation. Nordic theatre was world-leading in this period, 1880 to 1930, the playwrights Ibsen and Strindberg were at the front of the theatrical avant-garde, and that’s who these composers were writing music for. Really redefining what theatrical music can do, and can be – and I loved it. And so when you start taking Sibelius’s music really seriously, it opens up new ways of thinking about his symphonies and his other music. And that led to this piece for the Anthony Burgess Prize. Which was very nice, doing that. That was great.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

How did your writing, then, start to move from academia towards articles and eventually books?

LEAH BROAD:

In my last year of undergraduate, I set up a review site called the Oxford Culture Review because I wanted a space for academics who were world leaders in their subjects to give their take on culture. So it was a place for long-form reviews by people who knew a lot about particular topics. Very often, when you get invited to review something, you’ve got 200 words, and you can give a brief impression, but you can’t mention ‘the producer has put so much work into this symbolism in the third act’ or whatever. And sometimes you need a longer form for constructive criticism. If something doesn’t work in a production, sometimes that’s the most useful criticism to get. Anyway, I set that up, and out of that, I was writing very regular cultural criticism. God knows why I decided to do that during my Masters and also my PhD. But, you know, I like to be busy!

And then I hit the end of my PhD, I had to decide what I wanted to do career wise. Making my work accessible and publicly relevant has been really, really important to me. I was always involved in access and outreach projects – from year one, as an undergraduate, I did all the open days and talks for schools, that was all so important to me. So when I was thinking about tanking years of my life into writing a book, I thought: ‘Do I want to write an academic monograph that costs several hundred pounds to buy that very few people are going to read and find it interesting?’ Maybe my mum won’t even find it interesting but she’ll read it dutifully!

JUSTIN LEWIS:

And so, with Quartet, did that start as the story of one composer which then became the stories of four composers?

LEAH BROAD:

While I’d been doing my PhD, I was accepted on to the BBC Radio 3 New Generation Thinkers programme and so my career was already moving in a more public direction. So, doing this broadcasting, I wondered, ‘What is the actual story that I think is important to tell and that a public readership might go for?’ I spoke to an agent, we talked through this list of book ideas, and I thought, I’d love to write one about women composers — but surely there’s no public readership for this, which publisher is going to take a punt on this? And he said, ‘No, Leah, that’s the book.’

We talked about what shape it should take, and we agreed that a group biography was right for various reasons – which I talk about in the introduction. Ethel Smyth would have been the person I would have done on her own because she’s definitely the best known, but she’s so unusual.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

I know it’s not all about the stories, but there are good stories about her. If this was a rock star’s biography, you’d be intrigued.

LEAH BROAD:

I really hope she gets a big public biography. She deserves it, desperately needs it. But I really wanted to show that music by women is more than Ethel Smyth because a lot of people have heard her name and said [Dismissively], ‘Don’t like her music. Women can’t write music.’ So I really wanted it to be more than her.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

We should probably explain all these four composers in turn, and your reasons for choosing them. Because their overlapping lifetimes cover a period from the 1850s to the 21st century. Would you like to introduce them, one by one?

LEAH BROAD:

Okay. Ethel Smyth is my first composer. She was an utterly extraordinary woman. She was a composer of six operas at a time when it was thought not just improbable, but biologically impossible for women to write great music. She had all of those operas staged in her lifetime. She was also a militant suffragette. She was imprisoned in Holloway for her militant suffrage action. She was lovers or friends with pretty much anybody interesting in the early 20th century, including Emmeline Pankhurst… Virginia Woolf, not lovers with her, but wanted to be. She really was a pioneering figure.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

Oscar Wilde’s brother [William] has a walk-on part in her story.

LEAH BROAD:

Oh yes, she was briefly engaged to Oscar Wilde’s brother! And then got bored of him, so turned him down! [Laughs]. What a hero! There are so many times now, if I’m feeling uncertain of myself, I think, ‘What would Ethel do?’ And then I don’t do that because I’d probably get banned! But I will do a more muted version, slightly more confident than how I’d instinctively be.

Rebecca Clarke is my second composer, also a viola player, and she is probably most famous for her Viola Sonata that she wrote in 1919. She was acknowledged as one of the pioneering modernist composers in Britain in the 1920s, and had a stellar career as both composer and performer.

My third composer is Dorothy Howell, a composer and pianist. She is definitely the quietest woman in Quartet. She was a Catholic composer, a lot of her choral music was written for the Catholic Church, although she was predominantly an orchestral composer. Her big pieces include Lamia – also from 1919 – an orchestral tone poem based on a poem by Keats which was a whirlwind success at the Proms where it was premiered. Her other big works include a Piano Concerto, which also premiered at the Proms with herself at the piano, a ballet called Koong Shee, and The Rock, a big orchestral work. And also some symphonic dances called Three Divertissements.

Doreen Carwithen, my final composer, the youngest of the four, was mainly a film composer, and also a very good pianist, but she didn’t have the same public career as Dorothy Howell. But I mean… I adore her music.

And the reason for these four… I don’t think you can accurately write a history of British music in the 19th or 20th century without including Ethel Smyth. It’s been done before, and I think it’s very wrong. And it’s led to the perception – Benjamin Britten promoted this narrative himself – that British opera before Britten was Purcell. No, actually! Ethel Smyth was a DBE, the first woman to be made DBE for composition. You know – she had three honorary doctorates in music. She was a celebrity, and her operas were really important to the story of British opera in the early 20th century.

So Ethel Smyth was always going to be in Quartet. She, Rebecca Clarke and Dorothy Howell made a very natural trio because in their lifetime they were thought of as the three leading women composers in Britain. They all pleasingly had very different personalities and were good at different things and so they lend themselves well to being the first three composers in Quartet. For the fourth composer, I kind of wanted to stretch into the 21st century… and it could have been so many people actually because there were so many women composing. It was almost Elizabeth Maconchy, but I really wanted somebody whose music was stylistically similar to that of the other three women. It already felt like an enormous book, and if I’d started writing about the stylistic change of modernism in the 20th century, it would be too massive.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

That felt like a different book?

LEAH BROAD:

That felt like a different book. And one day I hope to write about Elizabeth Maconchy, Grace Williams, Elisabeth Lutyens – and Ruth Gipps staunchly holding up her flag: ‘No modernism here!’ But I ended up choosing Doreen Carwithen because she was a film composer, still something that’s considered a bit unusual for women to do today. I wanted to show that actually there’s a precedent, that there’s this woman who was very successful in the 40s and 50s as a film composer.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

To the extent of composing the music for the Pathé documentary on Queen Elizabeth II’s Coronation in 1953.

LEAH BROAD:

Yes! And dubiously credited! She comes up as the ‘conductor [Adrian Boult]’s assistant’. So not quite completely uncredited, but she did write original music for that, she arranged all the pieces you hear on that soundtrack, and she had to do it extraordinarily quickly.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

Yes, didn’t it have to be in the cinema the following day, the following morning?

LEAH BROAD:

Yeah, because there was a kind of a competition between two production companies to see who could get their movie out first, because whoever did was going to make bank, basically. And so it was worth a lot of money to them to have a good composer who was quick. And she was the woman they trusted. And they were right – that film went out first. So she was really going places and.it seemed like an important story to tell as well because she did something that the other three women did not do. She married someone and wrote herself out of the narrative by promoting her husband [the composer William Alwyn], and I wanted a woman who represented that kind of story because it’s such a familiar trope.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

It’s interesting that Carwithen is the most recent of the four composers – if you’d known nothing about any of them, you might presume the earliest of the four composers would suffer that fate. In fact, it’s worked the opposite way – Smyth, the most apparently ferociously independent – is probably the best-known. The ones who have come since have fallen away from the limelight, often out of whatever was in fashion at time, or even conscious erasure.

Even with Smyth, after she died, her music wasn’t really performed very much anymore, and she was castigated for ‘not making it all about the music’. But to some extent as a pioneer, you have to put that personality forward.

LEAH BROAD:

Maybe this is going to sound off-tangent, but it’s not, I promise! I watched Oppenheimer, this huge behemoth of a biopic that really is about ideas and intellectualism. And I just thought it would be so nice to see a movie like that about a historical woman – but also it would probably be a bit of a lie. Because women having to fight against gender prejudice is such a definitive aspect of historical women’s experience that it would be very difficult to make that kind of film in parallel without it tackling gender dynamics. So it’s so frustrating for women like Smyth who desperately wanted it to just be about the music, but who found that she couldn’t, because people forced her to say, ‘Yes, okay, I’m a woman, let’s talk about that and then we can talk about the music’ – because she was always approached as a woman first and an artist second. She was so desperate to be taken seriously that she wanted to hide the fact that she was a woman at all. Her first works were out under the name ‘EM Smyth’ rather than ‘Ethel Smyth’. Because as soon as people realised she was a woman, that became the foregrounded thing. I don’t think she wanted to be exceptional as a woman; she wanted to be exceptional as a composer AND as a woman. It was impossible to be anything other than exceptional as a woman, and I think that’s why, when she kept hitting up against this, she was, ‘Alright then, I’ll meet you where you are forcing me. Yes, I’m a woman – what you going to do about it?’ Whereas other women, I think, just gave up and crumbled under that kind of relentless exceptionalism.

But definitely in her early life, she had no interest in being viewed as a woman at all. Given the constraints of her time, I think if she could have chosen her gender and just allowed herself to be viewed primarily for the quality of her music, she would have absolutely, without hesitation, dispensed with any gender.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

Yes – when her work first gets performed in public in England, at Crystal Palace in about 1890, there she is as ‘EM Smyth’ in the programme, but the crowd are euphoric, and they go even more nuts when she appears, to take her applause, and they see she’s a woman. That’s something to note, too – how often you mention premieres of these composers’ new works, and the public often really take to them, really like them.

LEAH BROAD:

Well, yeah – and I think this still persists as a kind of double conversation. As an example, take the Lost Voices tour [featuring music covered in Quartet] which I’ve been doing with Fenella Humphreys [violin] and Nicky Eimer [piano]. Audiences who have come to that have been so blown away by the music. What’s been particularly lovely is people often come up afterwards and say they like Dorothy Howell the most, but they’ve never had the opportunity to hear it before then.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

Would it be true to say that she’s the least recorded of the four of them?

LEAH BROAD:

Absolutely, for sure. And that’s changing. Rebecca Miller has been doing incredible work to promote Howell’s orchestral music, and has just brought out the premiere recording of her orchestral works [in 2024]. So little of Howell’s music was published during her lifetime, so it wasn’t recorded and then wasn’t broadcast. But Howell has this really accessible but quite restrained style that a lot of people really want to hear – at least people who’ve been speaking to me after the concerts.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

We should say that she tried to destroy a lot of her music while she was alive, and it was only the quick thinking of the people around her that saved all this. That must have been challenging to go through that archive.

LEAH BROAD:

Yeah, it was challenging both emotionally and physically – with a lot of it, her niece and nephew have done their best to preserve it as best they can. But it’s material that needs a professional archive, and archive conditions to be preserved because some of it’s on trace paper, on very old manuscript paper, and it will disintegrate if it’s not taken care of properly. So that’s an ongoing conversation. Also, it’s just so sad knowing that she suffered quite badly from depression at the end of her life, and a lot of that was to do with her music being completely ignored. There are fewer things sadder for composers than to know your music is going to die with you. And so, she thought, I’d better destroy it. Merryn, her niece, was telling me how she saw Dorothy ripping up her pages, and saying, ‘Come on, Dorothy, don’t be silly, nobody wants this.’ It’s just heartbreakingly sad, that prejudice around gender basically led to this.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

Quartet was published about two and a half years ago, March 2023. What are the most important developments you’ve noticed since its publication, and in terms of these four composers, are there particular recordings you can recommend to people?

LEAH BROAD:

Absolutely. The world premiere recording of Ethel Smyth’s second opera Der Wald with the BBC Symphony Orchestra and BBC Singers, and John Andrews conducting – that’s a big one. I’m so glad that has come out. Then: Rebecca Miller’s recording of Dorothy Howell’s Orchestral Works – that’s a big, important one. And the pianist Samantha Ege has just recorded Doreen Carwithen’s Piano Concerto – there are many more performances of the Carwithen, the piano concerto has really taken off. Pianists seem to love that. And when you look at the number of performances of Doreen Carwithen’s music in the last few years – really shooting up. Programmers, performers and audiences are all really embracing her, which is so encouraging to see.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

And Quartet seems to have crossed over to a readership who might not normally have read a book about classical music.

LEAH BROAD:

I hope so. It’s always hard talking about your own work! I’ve had some really lovely feedback from readers, and I know for sure it has reached people who didn’t know anything about classical music before coming to it. It’s lovely that people can come to classical music through this music by women. One person said to me: ‘Oh I discovered Beethoven through this!’ I wanted these women to be remembered and I wanted their music to be heard. It’s so important to get that music out there so people can make up their own minds about whether they like it or not.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

Are you able to say what your next book is about?

LEAH BROAD:

For sure. It’s about women in music in World War II. My composer of choice, and there’s only one in this next book, is Avril Coleridge-Taylor. And so there’s a world premiere recording of her Piano Concerto and Orchestral Works coming out in November. Again, John Andrews conducting, with the BBC Philharmonic, Samantha Ege on piano – my dream team.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

Avril Coleridge-Taylor, when I put her name into the streaming service search engine, almost nothing came up, I think I’m right in saying.

LEAH BROAD:

Yes, there’s one recording of ‘Sussex Landscape’ by the Chineke! Orchestra, and then there’s a transcription of two of her songs for cello and piano. Here endeth the lesson. Yeah, it’s a really tiny discography, and that was why it was so important to get this recording done. John and I have been working on a series of recordings of world premiere recordings of women’s compositions, and this is building off the one we did of Grace Williams’ Orchestral Works with the BBC Philharmonic [released in 2024]. So this Avril Coleridge-Taylor collection is coming out to coincide with the book – and I’ve got some other recording projects in the works as well to really get her publicly available, and a lot of that is going to involve publication because none of her orchestral works are published.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

That must feel so extraordinarily rewarding for you, that you are able to revive these people’s works, that might otherwise just never be covered.

——

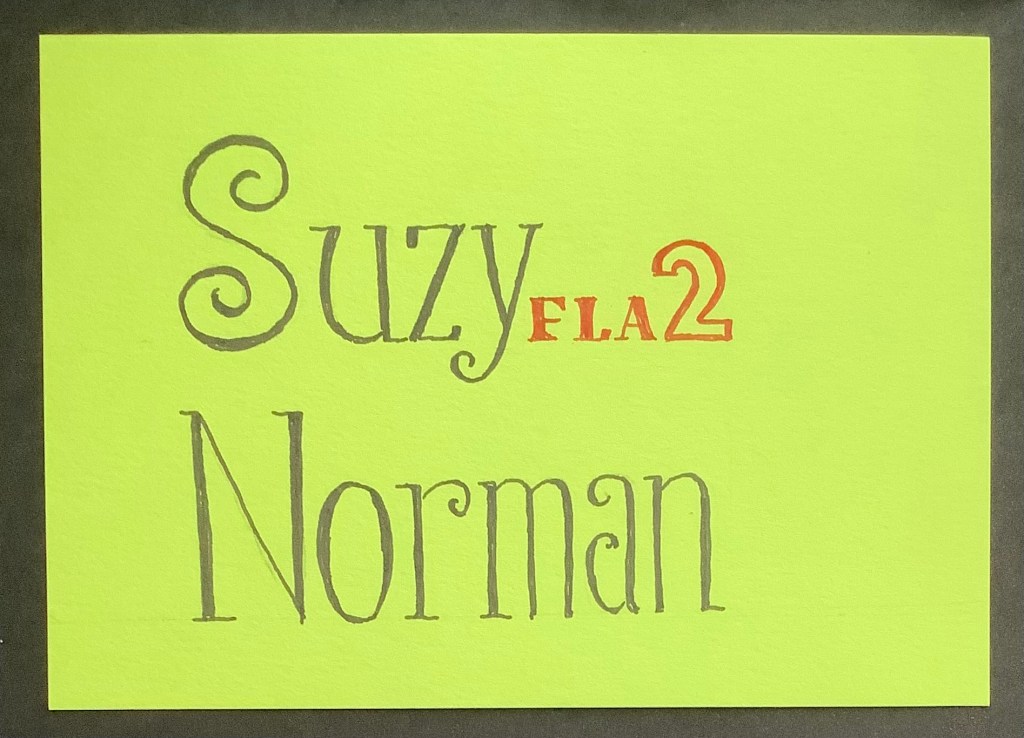

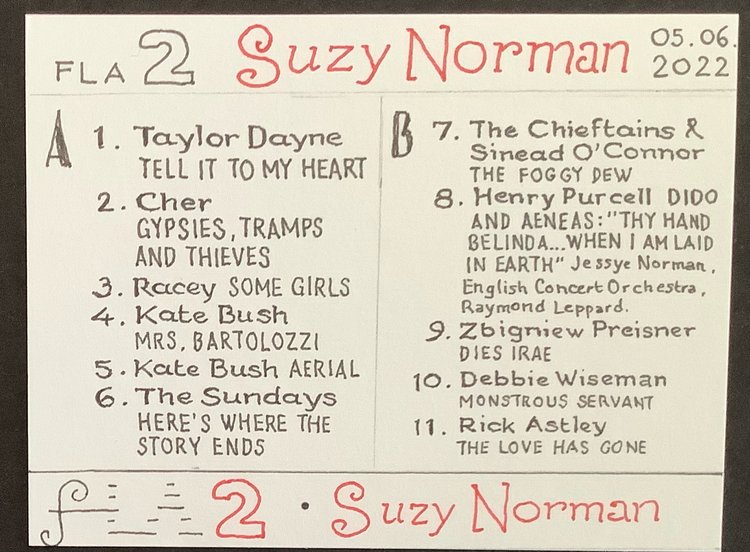

LAST: WDR SINFONIEORCHESTER/ELENA SCHWARZ: Elsa Barraine: Symphonies 1 and 2 (CPO, album, 2025)

Extract: ‘Pogromes’

LEAH BROAD:

Because I’m writing about women in World War II at the moment. We’re so used to thinking about men as political thinkers and political writers and wartime composers who obviously responded to the war in their compositions. It would be odd if all these women living through World War II were not responding creatively in any way. Elsa Barraine was fascinating, she was one of the few French composers who really opposed the Occupation, and refused to perform under those conditions. She was arrested by the Vichy police and later she had to go into hiding – she was of Jewish descent.

Just an utterly fascinating and extraordinarily brave woman who wrote really interesting music – that, as you observed, has lapsed out of popularity. So I was utterly delighted to see this come out because I’d gone to look at her scores in Paris, I thought, Oh my God – this woman needs an outing.’ And here it is. Hurray!

JUSTIN LEWIS:

Obviously, Elsa Barraine has been performed at the Proms this year, 2025. and one of the things I’m putting at the end of this conversation is a playlist compilation of available works by women composers for this year’s Proms. Obviously not everything’s on there, although a surprising amount is.

LEAH BROAD:

Well, it’s not a surprise – for the reason that when programmers come to programme a piece, the first questions they ask are: ‘What’s the instrumentation?’, ‘Where’s the score?’ and ‘Where’s the recording?’ So they can hear whether it fits with the rest of a programme – and this is one of the biggest barriers with programming unusual works. If you have to say, ‘Well, actually, there’s no recording, the score’s in an archive, and I can tell you the instrumentation but you’ll need to run it to be able to work out the full timing and actually, the score’s in a bit of a mess’… that’s a huge lot of work when you could just google Beethoven’s Fifth, with the bonus that the performers already know Beethoven 5 because they’ve played it a hundred times before.

When Glyndebourne did Ethel Smyth’s The Wreckers [in 2022], they made their own edition. When [conductor] Odaline de la Martinez did The Wreckers at the Proms in 1994, she made her own edition. So that’s a huge barrier, because it’s a lot of work when multiple editions of Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony just come up for free on IMSLP [the International Music Score Library Project]. So it’s actually not a coincidence that performed works at the Proms have been recorded – it’s an important point. Recording this work is crucial to getting it performed because nobody programmes music they don’t know.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

Looking at what’s on at the Proms in summer 2025, and I’m asking this from very much an outsider’s perspective, but it still feels unusual to have music by women as the headlining work at a Prom. Obviously, there are women with their own Prom – Anoushka Shankar and St Vincent spring to mind this year – but it’s still relatively unusual in the classical world, would you agree?

LEAH BROAD:

Absolutely. I was so pleased when they did The Wreckers in 2022. I was like, Thank god. The Proms is a huge festival, they have more latitude than a lot of music festivals to take some risks with programming. But having said that they are trying to fulfil a lot of different competing wants, and I think headlining unusual or unfamiliar works to an audience is perceived as a bit of a risk financially, for a venue of that size. There’s still the practicality of bums on seats, which can be tricky because sometimes the weirdest things impact on whether an audience turns up – sometimes it’ll be too hot, or there’s a tube strike, completely unrelated to the music in question.

This is why I come back to recording and broadcasting as the fundamental base block for getting this music performed more broadly, because then people can go, ‘Oh I heard that on Classic FM, I liked it.’ And so then programmers are less scared that when they put on Doreen Carwithen’s Suffolk Suite, nobody’s going to turn up because they have no idea who Doreen Carwithen is. This is why I always look through the Proms programme and look for the women they are there – but the title will say, for instance, ‘Mahler’.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

Yes. You have to go to each event’s webpage and click on it to see the full programme, not just the headlining work. A good example of that was the other night, when they had Dvořák’s New World Symphony televised on BBC Four and that was how it was billed, but the first half of the concert also had three less-heard works: Adolphus Hailstok’s An American Port of Call, Jennifer Higdon’s blue cathedral, and Arturo Márquez’s Concierto de otoño for trumpet.

LEAH BROAD:

It was the same when I did the radio interval for the Prom [31 July 2025] with Elsa Barraine [Symphony No 2], Aaron Copland [Clarinet Concerto], Artie Shaw [Clarinet Concerto] and Rachmaninov’s Symphonic Dances. And Rachmaninov and Copland were the headlines. And it’s because everyone goes, ‘Oh! Rachmaninov’s Symphonic Dances! Yes, I’ll buy tickets for that’ – but then they can hear Elsa Barraine as well. What I love about the Proms programming is that I trust their promoters to know what they’re doing in terms of getting people there. But also they’re doing a great job of matching up works, and of not token-womaning in the programme (where you’d turn up to a concert, and there’s an aesthetically coherent programme – and then a piece by a woman that sounds completely different, it doesn’t bear any relation to the rest of the programme). That Prom I just mentioned was all World War II [era] music, or from roughly around that period. So it made sense as a programme.

Credit where it’s due, I think the Proms are doing a pretty good job of integrating women throughout the season, both contemporary and historical. They’ve done quite a lot recently – they’ve done some Ruth Gipps, they’ve done Avril Coleridge-Taylor – ‘A Sussex Landscape’, with the Ulster Orchestra in 2024… Yes, there’s still stuff to work on. When you look at the duration of pieces by women…

JUSTIN LEWIS:

Yes, that occurred to me. There’s a lot of ‘oh, there’s a work by a woman but it’s four minutes’.

LEAH BROAD:

Yes, concert openers, right? Exactly. But I think this stuff is a process, and fair enough, people need to go at a pace that is sustainable for them, financially, and take audiences with them. I think there’s a lot of fear about programming music by women because people are worried that audiences aren’t going to turn up. So I do want to give credit to venues and festivals that are pushing ahead and are putting this music on programmes. Overall they’re doing a really good job.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

It does feel, fingers crossed, this is not going to be treated like a fad. This is going to continue to evolve.

LEAH BROAD:

I hope so. See what happens in America, because a lot of funding comes from America. And if American private philanthropy starts being entirely redirected to US audiences and venues – because the public funding’s being stripped away – then the UK infrastructure gets impacted as well. Let’s see…

JUSTIN LEWIS:

Maybe I’m being a bit optimistic!

LEAH BROAD:

Put it this way, we aren’t going to lose all the stuff that has been done in the last few years, so if nothing else, there’s a lot more material available now for programming than there was 30 years ago.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

The Internet I’ve also found so helpful with gathering together so much information and material about some of these forgotten figures. Just in terms of realising how many women composers there have been in history. There are, it turns out, thousands and thousands.

LEAH BROAD:

But a lot of this is building on work that was done in the 70s and 80s by women like Sophie Fuller who did the Pandora Guide to Women Composers [published 1994], and she went round, she did this archival work, and she has interviewed the women, and she has bloody well gone and done the groundwork. Then there were these big volumes by these big pioneering musicologists of the 70s and 80s, Jane Bowers and Judith Tick, Women Making Music [first published 1986]. It’s because of them that a lot of these women’s names have persisted and so because of that work, we can now start to go and do way more archival work. Which is still really important. Digitisation is great — like the British Newspaper Archive, for example – what a bloody godsend to have all this digitised material! But I really want to stress that not everything is digitised. Sometimes there’s a perception that if it’s online, that’s all there is, that everything’s been uploaded and digitised now. But especially writing about World War II, this is super not-the-case. There is still so much to be said for going to an archive and looking at the material and getting down and dirty with the historical manuscripts, and with the material from the time. Because so much digitisation is really selective – you’ll sometimes find one random newspaper hasn’t been included for digitisation, for copyright or legal reasons or something odd.

One of the women I’m writing about [at the moment] was a Nazi musician. She was rehabilitated, almost, immediately after the war, and it’s now very clear that she was very important during the Nazi regime. Some of the press around her has been digitised – some of it really has not, and it’s incredibly revealing! So it’s still really important to do the archival stuff.

——

ANYTHING: DOBRINKA TABAKOVA: String Paths (ECM, 2013)

Extract: Cello Concerto (Kristine Blaumane, Lithuanian Chamber Orchestra, Maxim Rysanov):

I. Turbulent, Tense

II. Longing

III. Radiant

LEAH BROAD:

How did I even find this? I think I interviewed a conductor who’d been performing Dobrinka’s music, and she mentioned that her music was one of the things she’d most enjoy conducting. So I went and looked her up – and there is nothing she’s written I haven’t absolutely loved. I defy anybody to listen to the Cello Concerto on this disc and not just have their heart stop.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

I am going to buy this one. You actually said to me when we were discussing choices on email, when I asked about the ‘Anything’ category: ‘I think this one has to be String Paths.’ It was that emphatic!

LEAH BROAD:

Yes, I evangelise about this to anyone whenever I get the opportunity. My goodness, that particular album has got me through some pretty miserable times and it means a great deal to me. So whenever I’m asked to pick a piece that means a lot to me, it’s probably going to be that Cello Concerto. It’s just one of these pieces of music that has absolutely everything in it.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

I noticed that she’s used a lot of the musicians on these recordings she had been studying with at college in London [Royal Academy, Guildhall, King’s]… and I was thinking, How exciting that must be – to have composers and musicians collaborating in that way.

LEAH BROAD:

Collaboration is such a fruitful way of writing music for a lot of composers, right? It’s absolutely fundamental to what they do. Everything she writes is so emotionally driven and intellectually fruitful. And she has a way of kind of speaking to the audience – it just works for me.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

I’m so glad you introduced me to this because I did not know about her at all. This is one of the reasons I do these conversations – there’s always a new name in the choices I didn’t know before.

LEAH BROAD:

Brilliant! Another convert!

——

Leah Broad’s Quartet: How Four Women Changed the Musical World is published by Faber Books. Her forthcoming book on women in music during World War II will be published in early 2027, and you can read an extract from the book here: https://www.whiting.org/content/leah-broad#/.

You can read plenty more about Leah and her work at her website: https://www.leahbroad.com/

I also must recommend Leah’s Substack site, Songs of Sunrise, with a plethora of her essays, articles and material. Check it out here: https://leahbroad.substack.com/

You can follow Leah on social media: on Bluesky at @leahbroad.bsky.social, and on Instagram at instagram.com/leahbroad.

——

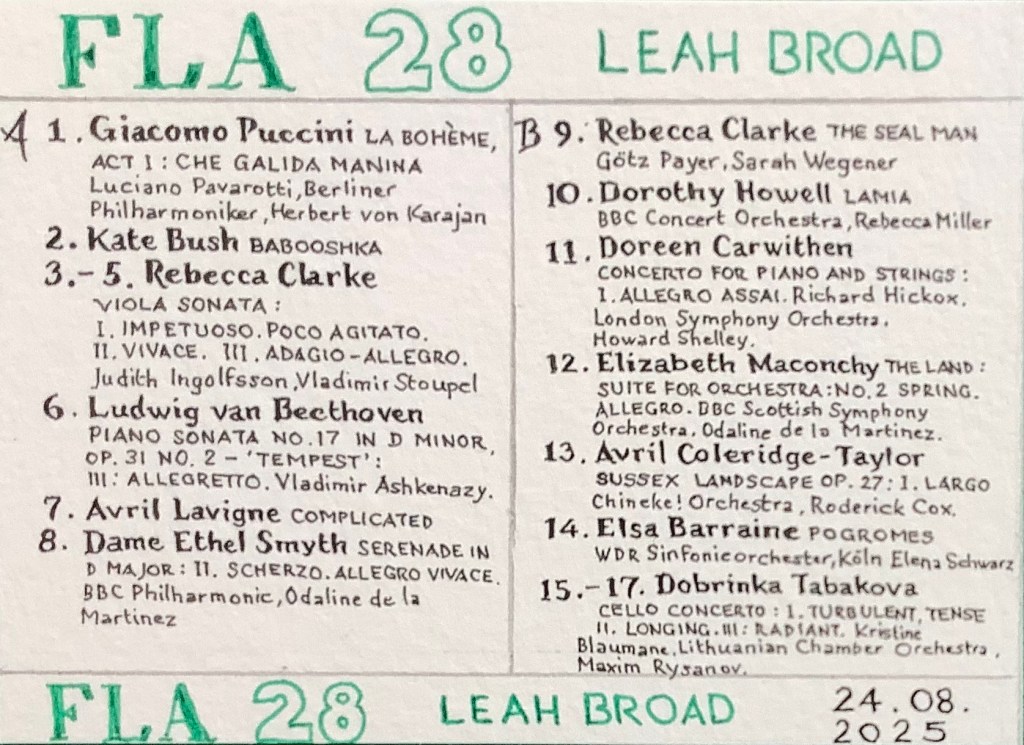

FLA 28 PLAYLIST

Leah Broad

(For the time being, this site and project uses Spotify for the conversation playlists, but obviously I disapprove that Spotify doesn’t pay artists and composers properly, and other streaming platforms are available, as are sites to buy downloads and buy recordings. For consistency, you can also listen to the selections via YouTube (where available), and links are provided in each case, below.)

Thanks to Tune My Music, you can also transfer this playlist to the platform or site of your choice by using this link: https://www.tunemymusic.com/share/hXx1vojBXq

Track 1:

GIACOMO PUCCINI: La Bohème: Act I: ‘Che Galida manina’

Luciano Pavarotti, Berliner Philharmoniker, Herbert von Karajan: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0DXtDcP4ESw&list=RD0DXtDcP4ESw&start_radio=1

Track 2:

KATE BUSH: Babooshka: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3NMhpI2-pLU&list=RD3NMhpI2-pLU&start_radio=1

Tracks 3–5:

REBECCA CLARKE: Viola Sonata

Judith Ingolfsson, Vladimir Stoupel.

- Impetuoso. Poco agitato: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pBKO8nwi1gQ&list=RDpBKO8nwi1gQ&start_radio=1

- Vivace: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xyHi9jGZWBI&list=RDxyHi9jGZWBI&start_radio=1

- Adagio – Allegro: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fDGkUELIW0k&list=RDfDGkUELIW0k&start_radio=1

Track 6:

LUDWIG VAN BEETHOVEN: Piano Sonata No. 17 in D Minor, Op. 31 No. 2 – ‘Tempest’:

Vladimir Ashkenazy:

III. Allegretto: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TQBBOZ8a0yg&list=RDTQBBOZ8a0yg&start_radio=1

Track 7:

AVRIL LAVIGNE: ‘Complicated’: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pjrBPHjCiuI&list=RDpjrBPHjCiuI&start_radio=1

Track 8:

DAME ETHEL SMYTH: Serenade in D Major: II. Scherzo. Allegro vivace:

BBC Philharmonic, Odaline de la Martinez: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ka2bpiucgq4&list=RDKa2bpiucgq4&start_radio=1

Track 9:

REBECCA CLARKE: The Seal Man:

Götz Payer, Sarah Wegener: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hvztghVqQBU&list=RDhvztghVqQBU&start_radio=1

Track 10:

DOROTHY HOWELL: Lamia:

BBC Concert Orchestra, Rebecca Miller: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HySxRaxwlRU&list=RDHySxRaxwlRU&start_radio=1

Track 11:

DOREEN CARWITHEN: Concerto for Piano and Strings: I. Allegro assai:

Richard Hickox, London Symphony Orchestra, Howard Shelley: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mqbgm8KTVwg&list=RDmqbgm8KTVwg&start_radio=1

Track 12:

ELIZABETH MACONCHY: The Land: Suite for Orchestra: No. 2 Spring. Allegro:

BBC Scottish Symphony Orchestra, Odaline de la Martinez: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HIoKkaKIHO4&list=RDHIoKkaKIHO4&start_radio=1

Track 13:

AVRIL COLERIDGE-TAYLOR: A Sussex Landscape, Op. 27: I. Largo:

Chineke! Orchestra, Roderick Cox: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JbT5NCaVgm0&list=RDJbT5NCaVgm0&start_radio=1

Track 14:

ELSA BARRAINE: Pogromes:

WDR Sinfonieorchester Köln, Elena Schwarz: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cazapIbpynQ&list=RDcazapIbpynQ&start_radio=1

Tracks 15–17:

DOBRINKA TABAKOVA: Cello Concerto:

Kristine Blaumane, Lithuanian Chamber Orchestra, Maxim Rysanov:

- Turbulent, Tense: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=utujACA3xa4&list=RDutujACA3xa4&start_radio=1

- Longing: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Rv0EvERYsQI&list=RDRv0EvERYsQI&start_radio=1

- Radiant: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7vPQmm7eeQI&list=RD7vPQmm7eeQI&start_radio=1

APPENDIX: WOMEN COMPOSERS AT THE BBC PROMS, 2025 PLAYLIST

As I mentioned in the above conversation with Leah, I decided to compile a playlist of works from women composers which are being performed at the 2025 BBC Proms, where I could find recordings (not available in all cases, but should this change, I will add new recordings to the linked playlist, and to the list below).

(For the time being, this site and project uses Spotify for the conversation playlists, but obviously I disapprove that Spotify doesn’t pay artists and composers properly, and other streaming platforms are available, as are sites to buy downloads and buy recordings. For consistency, you can also listen to the selections via YouTube (where available), and links are provided in each case, below.)

Thanks to Tune My Music, you can also transfer this playlist to the platform or site of your choice by using this link: https://www.tunemymusic.com/share/DNyCxrxx6p

Track 1: CHARLOTTE SOHY (1887–1955): Danse mystique:

Orchestre National de Lyon, Nikolaj Szeps-Znaider: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nIFAVyEJtWo&list=RDnIFAVyEJtWo&start_radio=1

Tracks 2–4: GRAŻYNA BACEWICZ (1909–69): Concerto for String Orchestra:

Primuz Chamber Orchestra, Lukasz Blaszczyk

- Allegro: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hvYOwIEPrLI&list=RDhvYOwIEPrLI&start_radio=1

- Andante: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=iITnM1ItrRk&list=RDiITnM1ItrRk&start_radio=1

- Vivo: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9KXDYTaDkAM&list=RD9KXDYTaDkAM&start_radio=1

Tracks 5–7: ELSA BARRAINE (1910–99): Symphony No. 2 “Voïna”:

WDR Sinfonieorchester Köln, Elena Schwarz:

- Allegro vivace: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OgFQgA2vzJc&list=RDOgFQgA2vzJc&start_radio=1

- Marche funèbre: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sx29-aPeGQU&list=RDsx29-aPeGQU&start_radio=1

- Finale: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LealxkhMDhU&list=RDLealxkhMDhU&start_radio=1

Track 8: GALINA GRIGORJEVA (b. 1962): Svjatki: V. Spring is Coming:

Else Torp, Estonian Philharmonic Chamber Choir, Paul Hillier: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2nEdpUzFMMw&list=RD2nEdpUzFMMw&start_radio=1

Track 9: AMY BEACH (1867–1944): Bal masque, Op 22:

Moravian Philharmonic Orchestra, Hector Valdivia: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LWds9q2md3o&list=RDLWds9q2md3o&start_radio=1

Track 10: GRACE WILLIAMS (1906–77): Elegy:

Royal Philharmonic Orchestra, Owain Arwel Hughes: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sWWjoX0KGqQ&list=RDsWWjoX0KGqQ&start_radio=1

Track 11: JENNIFER HIGDON (b. 1962): blue cathedral:

Atlanta Symphony Orchestra, Robert Spano: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dyOVPwYZR8w&list=RDdyOVPwYZR8w&start_radio=1

Track 12: MARIA HULD MARKAN SIGFÚSDÓTTIR (b. 1980): Oceans:

Iceland Symphony Orchestra, Daniel Bjarnason: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=p_LJtQ2FMqo&list=RDp_LJtQ2FMqo&start_radio=1

Track 13: ANNA CLYNE (b. 1980): Restless Oceans:

Kanako Abe, Orchestre Pasdeloup: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TAwFdBo4yNk&list=RDTAwFdBo4yNk&start_radio=1

Track 14: CAROLINE SHAW (b. 1982): The Observatory:

BBC Symphony Orchestra, Dalia Stasevska: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zqMK-eeO9nQ&list=RDzqMK-eeO9nQ&start_radio=1

Track 15: ANOUSHKA SHANKAR (b. 1981): Stolen Moments: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3Kcdme8DLTs&list=RD3Kcdme8DLTs&start_radio=1

Track 16: ETHEL SMYTH (1858–1944): Komm, süsser Tod:

SANSARA, Tom Herring: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-DtTONu4KGo&list=RD-DtTONu4KGo&start_radio=1

Track 17: ALMA MAHLER (1879–1964): Licht in der Nacht:

Iris Vermillion, Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra, Riccardo Chailly: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QO2CgGsKuRM&list=RDQO2CgGsKuRM&start_radio=1

Track 18: AUGUSTA HOLMÈS (1847–1903): Andromede:

Staatsphilharmonie Rheinland-Pfalz, Samuel Friedmann: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=e6TS_-wBc5M&list=RDe6TS_-wBc5M&start_radio=1

Track 19: MARGARET SUTHERLAND (1897–1984): Haunted Hills:

Melbourne Symphony Orchestra, Patrick Thomas: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gLhPqzXS68o&list=RDgLhPqzXS68o&start_radio=1

Track 20: HANNAH KENDALL (b. 1984): Weroon Weroon:

Pekka Kuusisto: [work currently not on YouTube]

Track 21: CAROLINE SHAW (b. 1982): Plan & Elevation: V. The Beech Tree:

Mari Samuelsen, Scoring Berlin: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hdO6rxBQomE&list=RDhdO6rxBQomE&start_radio=1

Track 22: RUTH GIPPS (1921–99): Death on the Pale Horse, Op. 25:

BBC Philharmonic, Rumon Gamba: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6x1ChTFr_Ck&list=RD6x1ChTFr_Ck&start_radio=1

Track 23: LILI BOULANGER (1893–1918): D’un matin de printemps:

BBC Philharmonic, Yan Pascal Tortelier: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5jW3mLOQ0Xc&list=RD5jW3mLOQ0Xc&start_radio=1