Alison Eales pic (c) Euan Robertson

Alison Eales is a musician, songwriter and arranger, whose splendid solo debut album, Mox Nox, is a captivating blend of folk, electronic music and found sounds of the city, namely the city of Glasgow where she has lived since the turn of the century. Released in Spring 2023, Mox Nox is already one of my records of the year.

Born in the south-east of England, Alison was raised in Berkshire, and then in Somerset. After university in Glasgow, she became the keyboard player and accordionist with Butcher Boy, who have made three studio albums to date, and released an anthology, You Had a Kind Face, in 2022. In addition, she has worked as a collaborator and arranger, has written a PhD on the Glasgow International Jazz Festival, and is currently working on a history of jazz in Scotland.

It was an absolute pleasure to talk to Alison on Zoom one evening at the start of August 2023, to hear about some of her working methods in composition and arrangement, her participation in choral music, and of course, some of the records which have inspired her, past and present. We hope you enjoy our conversation as much as we did.

—-

ALISON EALES

Until I was eight, we lived in Maidenhead, in Berkshire. I think my earliest memories of music in the house were the Carpenters, listening to ‘Goodbye to Love’ when I was really tiny, and my Nana was very into The Sound of Music – whenever we visited her, it was on – but my mum and dad were kind of folk singers who used to play guitar and sing. There was also quite a bit of stuff like Gordon Lightfoot and Tom Paxton. So lots of guitar-based, acoustic music at home.

But also, I’ve got a bit of a thing about old TV continuity, particularly idents. So there’s music from TV startups and jingles and things like that lodged in my head early on.

JUSTIN LEWIS

I often think of TV music from the past as being associated with waiting for things. When I first heard Air, who I love, it made me think of interludes and ‘Well, we’ll be back with children’s programmes later, but now here’s some music and Pages from Ceefax’. I seem to remember in the early days of the Internet, there was something called the Test Card Circle.

ALISON EALES

I was a member of that for a little while. They were based out of Edinburgh, I think. I’ve still got a load of the magazines somewhere. The main purpose of the Test Card Circle was to share trade test tapes of the start-up music and things like that. So there’s quite a lot of that library music that I really like now, and I think that goes back to when I was little.

There are composers and arrangers from that genre I love, like Brian Bennett, Alan Hawkshaw – and Keith Mansfield, who wrote the Granada TV start-up music [‘New Granada Theme’, 1979]. Granada didn’t have a jingle to accompany their logo, but he wrote that start-up music. And he wrote the Grandstand theme and the Wimbledon theme and ‘Funky Fanfare’, all that great library music. In the last few years, I’ve got very interested in the KPM Music Library.

JUSTIN LEWIS

Lots of it on streaming services now.

London Weekend Television: ‘River’ ident, 1970-78

JUSTIN LEWIS

Some genius uploaded a sequence of all the jingles considered for Thames Television before its launch in 1968 – and you can hear the variations which were considered. Really strange to hear the one they chose in amongst it, and you can hear they chose right.

Thames test idents, 1968 (the one at 1’20” is ‘the one’)

JUSTIN LEWIS

And there’s yet another one (1969–70), composed I believe by David ‘Jeans On/Channel 4’ Dundas, where they used this orange, white and black combination logo, which funnily enough made me think of your current album cover!

ALISON EALES

Maybe I stole it! Oh my god. [Laughter]

ALISON EALES

And there’s something so evocative about it. When I was very, very young, I remember thinking, ‘What does music mean?’ What does that sound mean when the LWT jingle comes into play on a Friday night: It’s the weekend! You know? They’re like time signals – ‘this little jingle tells you where you are in the week’ – so yeah, I love all that.

The LWT jingle was written by a guy called Harry Rabinowitz (1916–2016), who also did things like the soundtrack to Chariots of Fire. The jingle is, I think, meant to evoke the sound of Bow Bells – that little glockenspiel and then big fanfare.

ALISON EALES

Before they hit on the ‘river’ ident for LWT, they did one which was a Radiophonic Workshop-type jingle, and it’s crazy how you can think, ‘I can’t associate that with London Weekend. That’s not how it goes!’

London Weekend ident and jingle, 1968-69

JUSTIN LEWIS

But these colour schemes are very powerful, particularly when you’re young. And these associated bursts of music. Do you know of John Baker – I’m sure you do. [AE: Yes!] He did not only this Radiophonic Workshop arrangement of a Welsh folk song called ‘Tros y gareg’ for BBC Wales which was essentially ‘Programmes begin shortly’, but also the Harlech/HTV logo jingle.

ALISON EALES

Straight away, that HTV music – one of my favourites – is Robin of Sherwood to me. John Baker was on my mind when I made ‘Fifty-Five North’ because there’s a little ‘ding’ sound in it, that I sampled from the turnstiles on the Glasgow Subway. It reminded me of a piece of John Baker’s called ‘New Worlds’ which I saw the Radiophonic Workshop play about 10 or 15 years ago in Camden, and the very end of it got used as the jingle for Newsround. But there’s also all that melody made by John Baker striking bottles. So I’m absolutely delighted to have a little nod to John Baker in my own song, ‘Fifty-Five North’.

JUSTIN LEWIS

And we’ll come back to ‘Fifty-Five North’. There’s something quite haunting about a lot of that material.

ALISON EALES

I try not to wallow in nostalgia too much, but sometimes it can be a really sweet kind of melancholy.

FIRST: CULTURE CLUB: Colour by Numbers (Virgin Records, 1983)

Extract: ‘It’s a Miracle’

ALISON EALES

I was bought this by my mum and dad – I would have been three or four – because supposedly I just loved ‘Karma Chameleon’, would dance away to it whenever it was on Top of the Pops. But listening back to that album now, the song that strikes me as really underrated is ‘It’s a Miracle’.

JUSTIN LEWIS

Which is my favourite Culture Club single, I think. I used to presume ‘Karma Chameleon’ would be the one Culture Club would be remembered for, but it seems to have swung back to ‘Do You Really Want to Hurt Me’ of late. But this whole album is a great pop LP.

ALISON EALES

And I think the other thing that gets underrated about Culture Club is Helen Terry’s voice. On ‘It’s a Miracle’, she’s the driving force, what I love about that sort of 80s stuff, like Sarah Jane Morris with the Communards. These really soulful female singers coming through these bands. But Helen Terry gets relegated from Culture Club a little bit.

JUSTIN LEWIS

Yes, it’s never quite clear if she was a member of the group or not. Because she’s on lots of the records.

ALISON EALES

Her voice is such a big one. She’s like the Merry Clayton of Culture Club.

JUSTIN LEWIS

And it also makes me think of Alison Moyet’s records with Yazoo, that amazing combination, that tension between Vince Clarke’s electronics and her very bluesy voice over the top.

ALISON EALES

Yeah. Upstairs at Eric’s by Yazoo was also a key record in our house when I was growing up. It’s a very British response to disco – Vince Clarke came out of that post-punk landscape, a reaction to punk, the key elements of disco. Electronics and drum machines and a soulful female vocal.

JUSTIN LEWIS

And then selling that back to America. ‘Situation’ by Yazoo was a huge club record in America and all the DJs who would invent house music were listening to that and early Depeche Mode as well. And of course Vince Clarke was composing all the TV themes in the early 80s. All the pop shows.

—-

JUSTIN LEWIS

So how did you begin learning music yourself? Were you having lessons at school?

ALISON EALES

My mum and dad sent me for piano lessons when I was really quite young. But I think young children probably learn better by having fun with music. I’ve never really seen fully eye-to-eye with the piano. I never studied or practised very hard. I can read music, but I always preferred to learn things by ear. Later I had oboe lessons, which I hated even more, but I always enjoyed singing, so I used to sing in children’s choirs. You learn a lot in a choir, not just about music theory, but about musicality and musicianship and being able to interact with other musicians. I really valued that.

And because my mum and dad had both played guitar, there was always a couple of guitars lying around, and I did the typical teenage thing of picking up a guitar and playing Cranberries songs or whatever. This weekend just gone, I was in a charity shop and picked up a copy of Melanie’s first album, Born to Be (1968). I started listening to her in my mid-teens, just around that time I was picking up a guitar. There’s a particular song called ‘Close To It All’, and oddly enough I was in the studio a couple of weeks ago, playing it to my collaborator Paul Savage as a reference point, for something I wanted to sound like.

JUSTIN LEWIS

It’s funny, because when I hear the Mox Nox album, that you’ve released this year, I can hear folkier influences in there, but there’s electronics there too, and I guess I had assumed you were a bit of a keyboard whiz because there are keyboards all over that record.

ALISON EALES

I know my way around keyboards and around sounds, how to build sounds with a synthesiser. I’ve learned that from being in Butcher Boy because quite often John Hunt, who writes the songs, will have a particular sound in mind, usually a ‘movie sound’ – like ‘I want this to sound like John Carpenter’. The kind of music I play, in indie-pop circles, is not particularly challenging on any one instrument – which is good because I’m not particularly good at one instrument – but I think the skills needed are much more about what would work as a particular sound, or what would work in the arrangement.

I’d always thought of myself more as a songwriter, and in fact, the feedback I’ve had for Mox Nox has been, ‘You’re really good as an arranger.’ I’ll never be good enough to be a session musician, but I enjoy the process of thinking, ‘It’d be really nice to have this kind of synth sound,’ and then creating it from scratch.

JUSTIN LEWIS

How did the arranging begin, then? Because you were doing some in Butcher Boy, is that right?

ALISON EALES

That tends to be a group effort. John brings songs to the band, and we’ll all work on our own parts, and make suggestions to each other’s parts as well. But I’ve done vocal arrangements. There’s been a few things with multiple singers, and we did an EP (Bad Things Happen When It’s Quiet) with choral parts on it five or six years ago. It made sense for me to arrange those. I’ve done a little bit of string arrangement, but not that much as we’ve got two wonderful string players who are much, much better at that. And a couple of brass arrangements, although one of those ended up as a synth thing, actually. I just like getting stuck in, really.

JUSTIN LEWIS

How did you come to join Butcher Boy in the first place?

ALISON EALES

It was 2005. I used to go to a club night called National Pop League, a monthly indie-pop disco in Glasgow, that John used to run. It was at an old social club, and one night I got chatting to Garry Hoggan, who played bass in the band. And when he visited my flat, just off Byres Road, what caught his attention was that I had an accordion, because I think John had always wanted an accordion in Butcher Boy.

JUSTIN LEWIS

What had drawn you to the accordion, what was the appeal?

ALISON EALES

I think it goes back to being in my teens, getting into quite folksy stuff, and I remember saying to my parents, absent-mindedly, that I might like to play the accordion. So they got me one for my eighteenth birthday. I’ve never upgraded it – it’s nothing special but it sounds great.

JUSTIN LEWIS

As I understand it, they’re not easy to play.

ALISON EALES

Mine is a piano accordion. On one side, you’ve got a straightforward keyboard, and on the other, you’ve got buttons which play different chords and bass notes. Once you’ve worked out the pattern of the buttons, and learned how to control the flow of air, it’s quite intuitive.

JUSTIN LEWIS

I don’t think enough is made of arrangement in music. Because it’s not just about what you put in, it’s what you leave out too. And I’m interested in how someone like yourself makes those kinds of decisions. Were there particular arrangers who have inspired you?

ALISON EALES

Well, Angela Morley is the big one for me, a complete hero. Going back to the TV ident thing, she arranged the ATV ‘Zoom’ ident (1969-81) composed by Jack Parnell, ‘bing bing bing’.

When I hear a record I love, and I check the arranger’s name, I’m amazed by the number of times it’s her. Scott 4 by Scott Walker, one of my absolute favourite records. The soundtrack to Watership Down, which I don’t think she composed, but it’s such a beautiful arrangement. And going back to Keith Mansfield, he did the arrangements for some of my favourite pop songs – ‘No Stranger Am I’ by Dusty Springfield, with its staggering deployment of oboe, and ‘Peaceful’ by Georgie Fame.

JUSTIN LEWIS

The third track on your Mox Nox album, ‘The Broken Song’. I’ve read something you said about this one. ‘It was left deliberately unfinished to create room for experimentation in the studio.’

ALISON EALES

Yes.

JUSTIN LEWIS

So can you talk me through why that track in particular, and how you completed it for the record.

ALISON EALES

When I started writing that song, there were a couple of things happening in my life. One was that I’d fallen in love for the first time. The other was that I had started suffering with anxiety, which has characterised my whole adult life. And, you know, you can insert your own punchline here, about those two things being the same thing. I always thought that song was about my feelings towards this other person. I was happy with the song’s verses, but I could never settle on a chorus for it – I kept redrafting lyrics and in the end, before I went into the studio, I decided to just delete the choruses and see what was left.

I looked at the lyrics that were left, and they were all about anxiety. Not being able to concentrate, not being able to remember things. So I wrote some additional lyrics about the experience of what’s called derealisation, where you feel like you’re outside your body and disconnected from your senses. I wanted the song to sound queasy and uncomfortable, like two songs crashing together, and that’s why the verses and choruses sound so different.

JUSTIN LEWIS

Hence the title. ‘The Broken Song’.

ALISON EALES

Yes!

JUSTIN LEWIS

The first thing you did on your own, as far as I can tell, was an EP or single about ten years ago, ‘Land and Sea’. What did you learn from that, and how did that experience get you to the solo album, Mox Nox?

ALISON EALES

I like the Just Joans cover that I did, but I’m not so keen on the other two songs.

My main learning from that was about the limitations of home recording. At the time I was living in this big and echoey flat, but we had a little cupboard, a sort of walk-in wardrobe. So I sat on the floor inside that. Then I realised that I didn’t have a pop shield for the microphone, but I thought I could put a tote bag between me and the microphone. And I don’t know why it occurred to me to do this, but I put the tote bag over my head – I thought that was the best way to support this bit of fabric. An ingenious solution. So there I was, roasting hot, sitting on the floor of this cupboard singing these vocals with a bag over my head.

I got to the end and I thought: ‘I could have put this bag over the microphone.’ [Laughter]

JUSTIN LEWIS

With the recent Mox Nox, you’d just started making it, and then the first lockdown of 2020 happened, yes?

ALISON EALES

Yeah, I think I had two weeks in the studio, finished up on the Friday, took away all the rough mixes and backups of the files. And then the Monday was the first UK-wide lockdown. So it was quite fraught. And then trying to have those decisions about who’s coming into the studio. In the end, it was mostly just me and Paul Savage in the studio in the early days so it wasn’t too risky. We had a little recording bubble. I came away from the first recording session feeling a bit downhearted. I couldn’t imagine how it would all come together. But then around September 2020, I got Pete Harvey’s beautiful string arrangement for ‘Ever Forward’, and that fired me up again.

JUSTIN LEWIS

On one of the other tracks, ‘Goodbye’, I’ve read that you wanted a choir for that, but lockdown put paid to that, and so there’s something called a ‘robot choir’ instead.

ALISON EALES

Yeah. I wanted some of my colleagues from the Glasgow Madrigirls choir, of which I’m a long-term member, to come in and sing with me. Actually, they would have been on a few other tracks: ‘A Natural History of California’, ‘Mox Nox’, and ‘Through Hoops’, which has got little stacked harmonies at the end. But we couldn’t do it. It wouldn’t have been responsible to have half a dozen people in close proximity, breathing on each other.

So for the wee choir bit in ‘Goodbye’, I used a technique we use in the choir and which our director Katy calls ‘waffle’, which is when we are given a set of notes and we all sing around them in our own time. It makes a really lovely effect, so I did that. Tuning wise, it was awful, because I couldn’t hear anything by the end of it. So I said to Paul, ‘Why don’t we just pitch-correct this to within an inch of its life so that it sounds really artificial?’, so it sounds like a robot choir.

JUSTIN LEWIS

I love the album, and it’s really interesting to discover that it was made under lockdown, because I hadn’t clocked that at all. It sounds like a really open record.

ALISON EALES

I’m really glad you’ve said that, because my real fear was of making a record, doing it all myself and it ending up sounding suffocated. You need other people’s ideas and other people’s breathing space to avoid it sounding airless. I was particularly upset not to get the Madrigirls on it, and yeah, at times, it felt like it was just me and Paul in the studio in the middle of nowhere.

—-

LAST: LEMON TWIGS: Everything Harmony (Captured Tracks, 2023)

Extract: ‘Any Time of Day’

JUSTIN LEWIS

Lemon Twigs, now this was new to me. And the title tells you everything. Those harmonies which are so infectious must be heaven to you.

ALISON EALES

Yeah, I’m a complete sucker for anything with vocal harmonies, having sung in choirs all my life, but also thinking of all those acts I grew up with – ABBA, The Beach Boys, Carpenters… that’s a key selling point of all those acts. And like the Beach Boys and Carpenters, you know, they’re siblings.

JUSTIN LEWIS

They’re frighteningly young too, Lemon Twigs. I was a bit shocked.

ALISON EALES

They’re frighteningly young, and there’s only two of them and you’re like, ‘How are the two of you making all this noise?’ But they also have that wonderful thing of siblings singing together, like obviously the Beach Boys, their voices just blending together. Garry Hoggan, my co-writer, sent me a link to ‘Any Time of Day’, the first song of theirs that I had heard. But the Beach Boys wasn’t the first comparison I made – I thought, Steely Dan.

JUSTIN LEWIS

Todd Rundgren came to mind for me, and it came as no surprise that they’re massive fans.

ALISON EALES

I think the Guardian review of it said, ‘They’re trapped in a time loop and they keep going from, like, 1967 to 1976.’ That’s exactly it. But yeah. ‘Any Time of Day’ is a stand-out track for me, and ‘I Don’t Belong to Me’, and the title track. It’s really sophisticated stuff, and just gorgeous. I love it.

—–

JUSTIN LEWIS

Just one more question about found sounds. You bought a Pocket Operator?

ALISON EALES

Yeah, it’s amazing. It looks like a little calculator or game, made by a company called Teenage Engineering.

JUSTIN LEWIS

How much was it?

ALISON EALES

The one I bought was about £80.

JUSTIN LEWIS

That’s pretty reasonable, really.

ALISON EALES

Especially as a lot of their stuff is outrageously expensive. So you can record sound with this. And I tell you what got me thinking about it. I was on the Glasgow Subway one day, and I realised that one of the escalators was making a rhythmic noise that I’d have liked for ‘Fifty-Five North’. It was maybe not quite swingy enough for the track, in the end, but I had the idea to try and record something on the Subway. You can record up to 30 seconds of sound, and then you’ve got a little set of sixteen buttons, and you can capture this little fragment of sound, and pitch it up or down a bit. And I got the result I wanted in the end, because of the Glasgow Subway, for ‘Fifty-Five North’.

JUSTIN LEWIS

So the main beat is a sample of the train doors closing?

ALISON EALES

Yeah. There’s a drum machine as well, which I wasn’t sure about leaving in, but it does give a bit of weight to the sound.

JUSTIN LEWIS

It made me think of the source material for ‘Bad Guy’ by Billie Eilish.

ALISON EALES

Oh yeah, the [pedestrian] crossing in Sydney.

JUSTIN LEWIS

It also made me think of Art of Noise, because they had one of the first samplers in the early 80s, and you could only record one or two seconds of sound which is why their records had these big stabs of sound.

ALISON EALES

Well, Trevor Horn’s a complete hero of mine, and I love Art of Noise as well. Was it the Fairlight CMI they had? Kind of a digital version of the Mellotron, absolutely fascinating instrument.

JUSTIN LEWIS

Didn’t Trevor Horn have one of the first in Britain? I think Kate Bush had one as well – ‘Sat in Your Lap’ has that all over it.

ALISON EALES

And Peter Gabriel too. There’s a South Bank Show documentary (LWT/ITV, 31 October 1982) of him making one of his albums [Peter Gabriel 4: Security], and he sits and demonstrates, using the Fairlight. Amazing. The other great bit of footage of a Fairlight being used is Herbie Hancock on Sesame Street (c. 1983). With a very young Tatyana Ali. She says her name into it, and he samples it. It’s very sweet.

—-

JUSTIN LEWIS

Let me ask you a little more about the Glasgow Madrigirls then, and the repertoire you do. How did you become involved in that?

ALISON EALES

I’d wanted to sing in a choir as an adult for a few years, because I’d enjoyed it so much as a child, but I’d never found one I wanted to join. But then about 20 years ago, a couple of years after the Madrigirls started, I joined. I had seen adverts up around the Glasgow University campus, looking for people to join this female choir. I dithered about it, but I was doing finals, so I decided against. But Katy Cooper, one of the two directors of the choir, was my flatmate, and she suggested that I audition. I wasn’t singing publicly at all at that point, although I had a sort of pipe dream of doing something solo. But this was before Butcher Boy, I wasn’t working in music and didn’t really know how to get started.

It was really nice to join Madrigirls. Originally, as the name suggests, the repertoire was mostly mediaeval and renaissance music – part songs and plainsong – but now it’s a mix of sacred and secular music from all over the world. I’m not religious at all, but we tend to do an Advent concert in December, a lovely festive shebang, and then in the summer, we go into folkier stuff, which is also part of Katy’s musical background, so there are arrangements of traditional folk songs. And we’ve commissioned some pieces over the years that have been really lovely as well.

JUSTIN LEWIS

How many are in the group now?

ALISON EALES

When I joined, it was sixteen of us. We would usually sing four-part harmonies. It’s about forty now.

JUSTIN LEWIS

A few years ago, you wrote a PhD about the history of the Glasgow International Jazz Festival, an annual event that began in the late 1980s, a full decade before you moved to the city. What was it about that event that made you want to research it? Were you a fan of jazz?

ALISON EALES

In 2010, [some years after graduating in English] I suddenly found myself wanting to do something academic that I could be proud of. I got a scholarship, and I was very lucky to go back to Glasgow University to do a Masters in Popular Music Studies, studying the history and theory of popular music. It was one of the best years of my life, really stimulating. I got to meet lots of great people, and the guy who ran the course, Martin Cloonan, was friends with Jill Rodger, the director of the Glasgow Jazz Festival. She had an archive of 30 years of artist contracts and publicity and all sorts of stuff. Martin saw the opportunity to get some funding for someone to do a PhD, and he secured funding, and then I was interviewed and got the position. But to me, the appeal was that I didn’t know anything about jazz, and so this was a great opportunity to immerse myself in it.

JUSTIN LEWIS

So can you give an example of a breakout thing you heard where you thought, ‘Oh, I’m so glad I’m researching this’.

ALISON EALES

It’s funny. Having said earlier on that, as a musician, I didn’t get on with the piano terribly well, I love it as a listener. I struggle a little bit with things that are brass or sax heavy, I really prefer piano jazz, but the exception to that, and the person I saw at the Jazz Festival who blew me away was Evan Parker, who I saw at the Recital Room at Glasgow City Hall. I don’t think he was even on stage. Maybe he was standing on the floor, so it was like he was in this small room on a level with you. He was playing soprano sax, just circular breathing and fully improvising, for five or six minutes, this constant sound, and I think it fundamentally changed how I think about what music can do, and how melody works. It was just so inspiring. And he was interviewed as well, and his politics are obviously very left, so I felt he was a good guy!

It was mad, actually. I got to meet people like Pharoah Sanders. I did artist liaison for Ginger Baker – twice!

JUSTIN LEWIS

Wow, you went back.

ALISON EALES

Let’s just say there were highs and lows. But I came away from it afterwards feeling very depressed, because I think the story [of Glasgow International Jazz Festival] is a story of declining commitment of city authorities to culture as a driver for tourism. The aim was to position Glasgow as a European Capital of Culture, and other European Capitals of Culture (whether they had that official title or not) all had jazz festivals. At the beginning, the people who ran it were given a blank cheque, and as time went on… I have a metaphor for it. It’s like you’ve done up your house, you’ve made it all beautiful, you have a big housewarming party, you’ve put up lots of decorations, and then afterwards, you take those decorations down with slightly less care than how you put them up. And invariably there’ll be one tiny bit of tinsel sellotaped into a corner of a room, and people might absent-mindedly notice that when they come to visit.

I think the Glasgow Jazz Festival is this little remnant of a time when there was a real commitment to culture as a driver of tourism. That was the tourism sales pitch for Glasgow from the early 80s onwards. Now it’s shopping. In the early days of the Jazz Festival, it was popular enough that you could get retailers to piggyback on it and sponsor it. By the time I was going to the Jazz Festival for research, I’d see a jazz-funk trio playing in the St Enoch Centre to completely indifferent passers-by and I’d just think, that sums it up.

I’m writing a history of jazz in Scotland at the moment. I don’t think Britain is receptive to jazz, full stop, the way they are in mainland Europe. But those of us who grew up in Britain in the 60s, 70s, 80s were absolutely surrounded by it growing up because of that TV library music, and all those arrangers we mentioned earlier. Keith Mansfield, Alan Hawkshaw, John Barry, some of our greatest TV and film composers… jazz was their background! It’s funny how there’s this resistance to jazz in the UK, and yet… the theme to Coronation Street, for heaven’s sake. Some of the music we hear the most is based in jazz.

JUSTIN LEWIS

Yes, jazz was massive in Britain once, in a mainstream way. There’s no real radio station that puts it front and centre anymore. And yet, once upon a time, in Britain, there were these three big musical areas: rock’n’roll, jazz, classical. (Four, actually. I forgot about folk.) And each had their devotees with markedly different opinions about the rival genres.

ALISON EALES

Yeah, you had the BBC Light Programme, especially in the 1950s, which would later split into Radio 2 and Radio 1. It’s interesting looking at the Light Programme and see where jazz and folk fitted in. It reminds me of that Stewart Lee routine where he talks about ‘jazz folk sex’. Jazz and folk being lumped together is really interesting.

It fascinates me, for all sorts of reasons. I could talk about this for hours, about early jazz festivals in Britain, programming folk singers, particularly Scottish folk singers. Early jazz was considered an African-American folk music, so there was some audience crossover.

JUSTIN LEWIS

And there’s something immensely spontaneous about both jazz and folk.

ALISON EALES

And the trad jazz stuff is fascinating as well. I mean, there’s divisions within divisions… people arguing about the value of different genres and subgenres. But that trad jazz boom of the late 1950s, early 1960s… the narrative is that beat music comes in and almost wipes trad jazz off the map. But I think what actually happened was that for trad jazz fans, that was their youth music. And they grew up, and stopped going out, while the next generation came along, with the Beatles and the Stones, who obviously made a lasting impact. But then you get this trad jazz revival in the late 70s, early 80s, you get people like George Melly back on the telly. It’s the nostalgia thing – the group of people who twenty years prior had been out dancing in the dance halls to trad jazz. Suddenly their kids are grown up and they have some spare cash and they can go out and dance again. It does seem to be a twenty-year cycle. You see it now with Britpop.

ANYTHING (1): JOANNA NEWSOM: Ys (Drag City Records, 2006)

Extract: ‘Emily’

[NB Joanna Newsom’s work is not available on Spotify and some other streaming services, else it would be on the FLA playlist at the end.]

JUSTIN LEWIS

You suggested two ‘Anything’ choices. When you mentioned this, I was just thinking about your work in arrangements, and the impact this must have made on you. I was reading up about how they made it, and apparently Joanna Newsom made the bare bones of the record first, voice and harp, and then Van Dyke Parks came in as arranger to build around the existing recording because of how the time signatures and phrasing worked.

ALISON EALES

Yes, I think at quite an early stage, she went to his house and literally played the album running order for him, and I think that was what got him on board to agree to do it. So she recorded the vocals and harp with Steve Albini. And then there are these points, on ‘Emily’ for instance, when it sounds like her and the orchestra are almost not in the same room, it’s hard to describe.

JUSTIN LEWIS

That artifice creates an interesting tension, because it is a recording. You can do anything.

ALISON EALES

There are enough decisions to make when you’re making a record, without tying yourself in knots about things like artifice and authenticity. There’s no point. It’s a rabbit hole you’d never come out of, so yeah. One reason I like working with Paul Savage is I can get really perfectionist about nothing, and I allowed myself that on Mox Nox, but I’ve just been working in the studio with Paul on this follow-up EP, and I took a different tack. I was like: ‘If something is good enough, it’s good enough.’ And Paul hates perfectionism, he likes things to be a bit rough around the edges, so it’s really nice to work with him, and so the next EP [hopefully out early 2024] is really minimalist.

ANYTHING (2): MASAYOSHI TAKANAKA: Can I Sing? (1983, USM Japan/Universal)

Extract: ‘Jumpingtakeoff’

JUSTIN LEWIS

Apparently he used to be a member of the Sadistic Mika Band, who supported Roxy Music on a UK tour in the mid-70s.

ALISON EALES

I didn’t know that. That’s amazing!

JUSTIN LEWIS

So what’s the story with this one?

ALISON EALES

One of my best friends in Glasgow is a guy called Colin Edwards. We’re both passionate about comedy and jazz – they’re our shared points of contact. And we found out we had lots of mutual friends.

JUSTIN LEWIS

Comedy and jazz – very similar art forms when you think about it.

ALISON EALES

Very. I read a great piece in The Quietus, where the author [Jennifer Lucy Allan, The Quietus, 27 Feb 2023] was writing about how Mulligan and O’Hare got her into improvised music. It was a really lovely love letter to Reeves and Mortimer, because seeing that kind of absurdist improvisation at a young age had got her into the kind of artists who were doing that for real. Stuff like Phil Minton! You can’t listen to that and not think, ‘There’s a comedy vein here.’

Comedy is a passion of mine. I’m always on the fence about ‘funny music’ in comedy, I find it can be very cringey, but I really love comedians who know what’s funny about music. I really love that. That is what I really appreciate.

Colin stumbled upon Takanaka on one of his YouTube binges. Initially, he was like, ‘This is really cheesy’ – again, it’s like library music, kind of highly polished and very slick. But then he got really taken in by how phenomenal this guy is. So Colin recommended him to me and it turns out that my co-writer Garry is a fan too. He’s an absolute legend in Japan – It’s become a dream to go there and see him live.

JUSTIN LEWIS

He seems to be very productive. This was his twelfth solo album, 1983, and he’d only been solo for eight years.

ALISON EALES

I don’t know if you’ve seen any live videos of him, but I strongly suggest you look up a couple of things. There’s a 2014 live version of this track, ‘Jumpingtakeoff’. He’s playing a guitar that’s carved out of a surfboard. Halfway through, all these balloons start raining down on stage, and he’s batting them away with this surfboard guitar. It’s just the most joyous thing. It should be available on the NHS. It’s the kind of music that, if you listen to it first thing in the morning, you feel like you can achieve anything.

JUSTIN LEWIS

It’s funny how Japan is like such a massive market for pop music, and only occasionally has something broken out and reached the UK.

ALISON EALES

Yes, I mean, obviously Yellow Magic Orchestra, and I love Sakamoto.

JUSTIN LEWIS

Pizzicato Five, too.

ALISON EALES

Yes, and Cibo Matto have broken out. Another album I got obsessed with a couple of years ago is Adult Baby by Kazu, who was in Blonde Redhead, who’s Japanese-American.

I think Garry started listening to Takanaka because of YouTube recommendations from Yellow Magic Orchestra. So maybe the algorithm is giving Takanaka a bit of a renaissance.

The other album of his that I just fell in love with is called Seychelles (1976), and there’s a version of that that’s all on ukulele, which sounds mad but it’s really beautiful. The last track on Ukulele Seychelles is a live encore. You can hear him interacting with the audience, and you can hear the love for him. He’ll play a little bit or sing a little bit, and there’ll be some laughter and some applause. He’s such a warm presence as well as a shit-hot guitarist. He has another surfboard guitar that shoots lasers out of the end of it, and an acoustic that’s got a model railway on it! [Laughter]

But I love that Can I Sing? album. ‘Santiago Bay Rendezous’ is really uplifting, and ‘Tokyo… Singin’ in the City’. The vocoder and stuff. It has all the hallmarks of slick library music, but it’s so playful and full of joy. I just think it’s wonderful.

—-

Mox Nox, released by Fika Recordings, is out now on vinyl and digital download.

Alison has since released one solo EP, Four for a Boy (in March 2024), and two digital tracks, Five for Silver (in March 2024) and Blue Dream (in December 2024). A remix EP, Through Hoops, was also issued in December 2024.

You can follow Alison on Bluesky at @alisoneales.bsky.social.

She also has a website: https://alisoneales.com

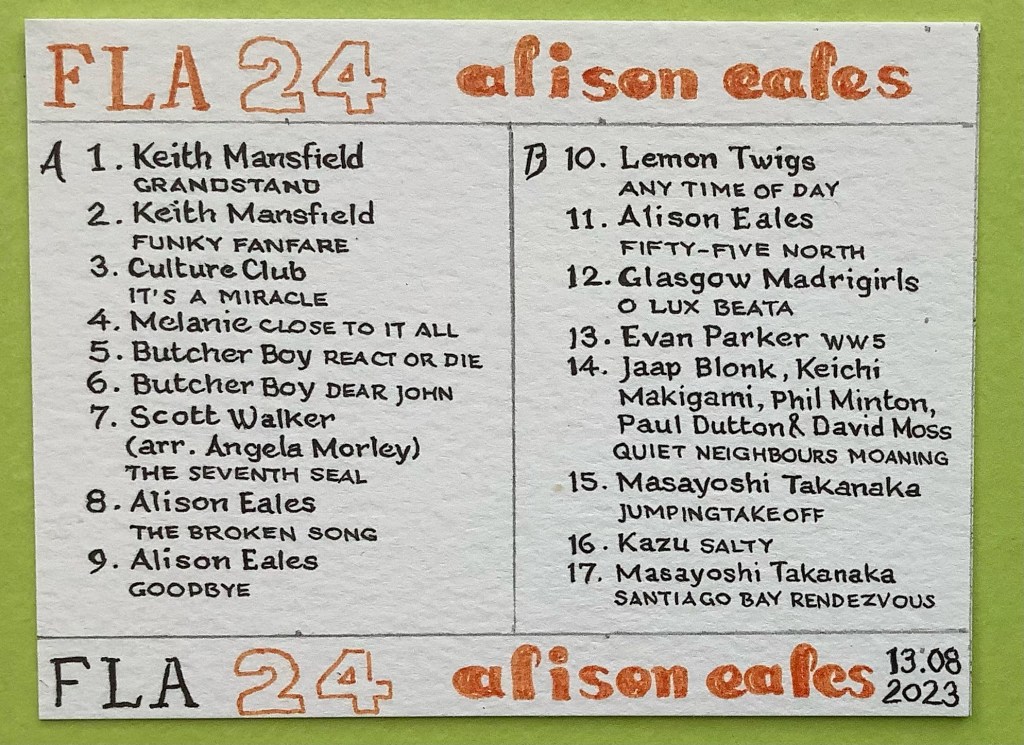

FLA PLAYLIST 24

Alison Eales

(For the time being, this site and project uses Spotify for the conversation playlists, but obviously I disapprove that Spotify doesn’t pay artists and composers properly, and other streaming platforms are available, as are sites to buy downloads and buy recordings. For consistency, you can also listen to the selections via YouTube (where available), and links are provided in each case, below.)

Track 1: KEITH MANSFIELD: ‘Grandstand’: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=C60ZtQaPfxQ

Track 2: KEITH MANSFIELD: ‘Funky Fanfare’: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tUFwQjOpqJM

Track 3: CULTURE CLUB: ‘It’s a Miracle’: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YewVugPHon4

Track 4: MELANIE: ‘Close to It All’: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Kd5rb2-WRp0

Track 5: BUTCHER BOY: ‘React or Die’: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7rigVP6FSMs

Track 6: BUTCHER BOY: ‘Dear John’: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yCQZcjWmWX8

Track 7: SCOTT WALKER (arr. ANGELA MORLEY): ‘The Seventh Seal’: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=J6XPXC-AKZ0

Track 8: ALISON EALES: ‘The Broken Song’: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6xo7WeIpcU0

Track 9: ALISON EALES: ‘Goodbye’: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IkofNhoWfBA

Track 10: LEMON TWIGS: ‘Any Time of Day’: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hmX2wsnzEGE

Track 11: ALISON EALES: ‘Fifty-Five North’: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Jjcf32H4V50

Track 12: GLASGOW MADRIGALS: ‘O Lux Beata’: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0Ub4IFK068M

Track 13: EVAN PARKER: ‘WW5’: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MtyG73Ujwzw

Track 14: PHIL MINTON: ‘Quiet Neighbours Moaning’: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rtK_fXQbMck

Track 15: MASAYOSHI TAKANAKA: ‘Jumpingtakeoff’: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=n6MNJc88jnM

Track 16: KAZU: ‘Salty’: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RtnkfcyQGps

Track 17: MASAYOSHI TAKANAKA: ‘Santiago Bay Rendezvous’: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IahB2YJ_yl8