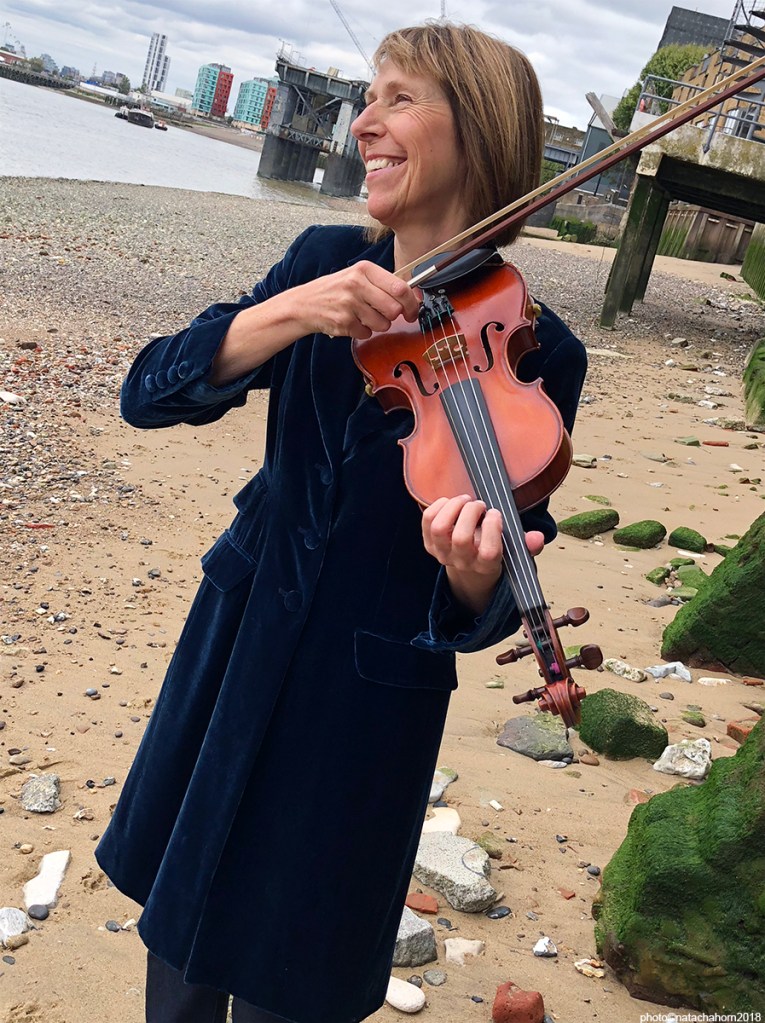

(c) Natacha Horn

In the spring of 1982, the violinist Helen O’Hara had two job offers. One was to join the Bilbao Symphony Orchestra; the other was to join Kevin Rowland’s Dexys Midnight Runners as part of their string trio, the Emerald Express. The release of the single ‘Come On Eileen’ and album Too-Rye-Ay made up her mind; the single alone would sell well over a million copies in Britain, and top the charts all over the world, even in the United States. Helen became Dexys’ musical director for their third album, Don’t Stand Me Down (1985), which received a mixed reception on release but has become widely and justly regarded as a masterpiece.

Though best known for her work with Dexys, Helen has had a busy life and career in music both before and after. For five years in the mid-1970s, she was an integral part of the Bristol music scene in bands like Gunner Cade and Uncle Po, but then turned her back on pop to study at the Birmingham School of Music (now the Birmingham Conservatoire). After the dissolution of Dexys, she went on to work extensively with Tanita Tikaram – most famously on her breakthrough single ‘Good Tradition’ – and most recently with Tim Burgess. In the summer of 2022, Helen and Dexys returned to the spotlight, performing ‘Come On Eileen’ at the closing ceremony of the Birmingham Commonwealth Games.

Helen has an excellent new memoir published this autumn, entitled What’s She Like, and I was delighted that she accepted my invitation to come on First Last Anything to choose some milestone recordings. As well as talking about her experiences in both the classical and pop worlds, she reveals why she stopped playing music for 20 years – and why she resumed.

—

JUSTIN LEWIS

In the opening chapter of What’s She Like you mention singles in your house that your siblings had and so on. But what records did your parents have when you were growing up?

HELEN O’HARA

Mainly classical records. Nothing unusual – Beethoven, Mozart… Tchaikovsky – whose Piano Concerto No 1 played by Van Cliburn was a particular favourite of mine. Nobody has beaten that version for me. Not just because it was very good, but because I heard it so much, it becomes ingrained in you at a very young age that ‘this is the best’.

My brother Tony, seven or eight years older than me, was the one buying the records and a big influence on what I heard. And Top of the Pops was on telly so I was exposed to other pop music which was making a huge impression on me, over classical music.

FIRST: PJ PROBY: ‘Maria’ (Liberty Records, single, 1965)

JUSTIN LEWIS

So the first record you bought yourself: PJ Proby. A kind of forgotten name now, really, but in his time, an absolutely massive pop star.

HELEN O’HARA

I can see why I was drawn to it. It really stuck out, mainly because of the orchestration but also because of his voice. He’s very theatrical. In fact, he was an actor for a while, I think, so his diction is absolutely amazing, but he’s got this drama in his voice, and he sings it as if he’s in a musical or an opera, telling the story. And of course, the song is from West Side Story.

It just blew me away really. Because I hadn’t heard anything like that before. Because my brother was already buying music like the Stones and the Pretty Things, which were my favourites anyway, I could buy this because it was more unusual.

I would have been nine, which is quite young to wander down to a record shop that’s about a mile away, with your pocket money and buy a record by yourself. It was just that incredible, proud feeling of owning this record – and he was a very good-looking bloke as well, so maybe that was part of it too! He had his hair in a ponytail, didn’t he? And then he got banned – from TV, radio, theatres – for splitting his trousers onstage, twice.

JUSTIN LEWIS

There’s a few versions of that story, but I read that apparently it was ‘accidental’ the first time, and perhaps ‘not so accidental’ the second time.

HELEN O’HARA

So he was well ahead of his time in terms of ‘how do I get publicity and censure?’

JUSTIN LEWIS

I think it was the ABC theatre chain that threw him off the package tour, but his replacement was some bloke, then unknown, called Tom Jones.

HELEN O’HARA

And Tom was pretty wild, wasn’t he? Probably didn’t deliberately split his trousers, but came close to it!

—

JUSTIN LEWIS

So you started playing the violin when you were about nine?

HELEN O’HARA

Nine, yeah.

JUSTIN LEWIS

You say in the book that you didn’t find it easy to play early on, indeed, have never found it easy. Presumably part of the appeal with the instrument is that that you can’t really take your eye off the ball. It requires commitment. It requires constant practice.

HELEN O’HARA

I think I just accepted that it was my instrument, and it was going to be difficult. I was so sure of it. It is a difficult instrument to play well, but I’m also extremely critical of myself. I wish I wasn’t, because I beat myself up an awful lot about any performance I do. And then when I listen to other people, I never have that criticism of them, I can be objective! Because it’s live, it’s human.

JUSTIN LEWIS

Obviously you started in the classical world, and you were in youth orchestras as a teenager. It sounds like you were already interested in ensemble playing, but perhaps individual expression within a group of some kind. Did you ever think you would be a solo violinist, in the classical world?

HELEN O’HARA

No, never. Never thought that. I always thought of myself within a group, preferring to be embedded in the group. I mean, if you’re the leader of an orchestra, as I sometimes was, you might have to take a little solo or something. But I much preferred being part of an ensemble.

JUSTIN LEWIS

And clearly you still love classical music, but I sensed in What’s She Like that the classical world back in the 60s and 70s could be a bit stifling, with little tolerance for any other type of music.

HELEN O’HARA

That’s how it felt, especially later at music college, because nobody seemed to listen to pop music. It was very rigid – it was just classical. Now music colleges, from what I can see, are open to all sorts of music – for example, they might have a jazz department. They recognise that instrumentalists could go in many directions – as much as anything, it’s about getting work, and so you’d be encouraged to play in musicals, or opera, or be a session violinist or whatever. I think they’re a lot more open minded now. I was still at college when I was recording Too-Rye-Ay with Dexys [in spring 1982], and we never mentioned it to the college, partly because they wouldn’t have given us the time off to do it, but another was that they’d have been horrified. Now, it’s very different.

JUSTIN LEWIS

It’s interesting how your memoir reflects these compartments of your life. You’re fully committed to something for two to three years, and then you move on to something else completely different. And that’s the pattern. But there’s still this sense of continuity throughout – you go back to things, to work with people again, after a long period of time.

HELEN O’HARA

I think you’ve got it. Yeah. Hadn’t thought of it like that, but yes, although not intentionally.

JUSTIN LEWIS

What also occurred to me: you come from quite a large family anyway, but all your musical exploits for years came with groups, large groups, orchestras. I might even suggest Dexys was an orchestra, certainly at the point you joined, with all the different sections.

And you write a lot about the people in music who have inspired you – some of them famous names, but others are fellow students, teachers… In fact, I don’t know if you remember this, but when you first got into the charts with ‘Come On Eileen’, you did a Q&A with Smash Hits magazine and they asked you your biggest musical inspiration. And most people in those Q&As would say David Bowie or Bryan Ferry or whoever. And you said Andrew Watkinson, your violin teacher. Who’s gone on to quite a career himself.

HELEN O’HARA

Oh, that’s really sweet. He was a real inspiration. Yes, he plays with the Endellion String Quartet now.

JUSTIN LEWIS

It really chimed with me at the time because I loved pop music, loved reading Smash Hits, but I also was in orchestras, I was a flautist, and I used to wonder how I could be in a pop group playing an orchestral instrument. But I thought that was such a cool answer – you didn’t choose a pop star, but your teacher. And to see you on Top of the Pops playing an instrument associated with the orchestra, I thought it was so cool.

In fact, in your book, you recall being about 13, trying to imitate the violin part on ‘Young Gifted and Black’ by Bob and Marcia. Well, when I was 13, I would – on the flute – try and imitate your violin parts on Dexys records, especially ‘Come on Eileen’ and ‘Let’s Get This Straight From the Start’.

HELEN O’HARA

Oh wow, that’s amazing.

JUSTIN LEWIS

I would try and bend the notes the way you would, try and work out how to do that. I’ve waited forty years to tell you that!

HELEN O’HARA

Ah, thank you so much, Justin. But it’s a great way to learn, isn’t it? When you play along. I remember playing along to some Roxy Music when Eddie Jobson was on violin.

JUSTIN LEWIS

Yes! The Country Life album.

HELEN O’HARA

I was even doing that in the 80s when The Waterboys’ Fisherman’s Blues came out, trying to imitate Steve Wickham, who’s a very different player to me. I still do it now, play along, because you can always learn a lot from somebody else’s style, can’t you?

JUSTIN LEWIS

Absolutely. What also comes across very clearly in What’s She Like is the importance of communality in music. How at secondary school, your music teacher ensured that all 600 pupils took part in the school concert, not just the really musical ones. Do you agree there’s musical potential in everyone?

HELEN O’HARA

Yes, I do. We’ve all got a heartbeat. Some people will be more musical than others, but often it’s whether you get the chance. I was also very lucky, when I was growing up, that we had free peripatetic music lessons, and everybody was offered a free lesson on whatever instrument, so that was amazing. My secondary school music teacher was quite young, probably in his mid-20s when he took on the job as head of music and he just seemed to spend all this time at school, encouraging everybody, and he would get cross with us if he thought we weren’t giving 100%. But that was cool, he was showing his passion for the subject. So, everyone had to sing in the concert we did, at the Colston Hall in Bristol. A lot of the boys didn’t like it – but they still all turned up! However, I think everyone admired him, and it felt good in that ensemble. It’s like being at a football match – you feel good when everyone sings together.

JUSTIN LEWIS

All the while, you were influenced by violinists in bands: Jimmy Lea in Slade, Don ‘Sugarcane’ Harris in Frank Zappa’s Mothers of Invention. And when you joined bands in Bristol, in your late teens, long before Dexys, where each album would be radically different from the last, you were already in groups that would change their style a lot. For instance, Uncle Po – with our mutual friend Gavin King… you’re a soul band (under the name Wisper), then you’re jazz rock for a bit, and about 1977 you become a new wave band. Did it feel easy to reinvent the band’s sound like that?

HELEN O’HARA

Very easy, very easy. Uncle Po were good musicians, good singers, good harmony singers – and we were very serious about what we did. We rehearsed for long hours, and we played live so much, and if you’re a good musician, you can adapt to different musical styles. I mean, it wasn’t like we had to be outright jazz or something, but within the different genres of pop or rock, we didn’t find that difficult. When punk and new wave happened, it shook everybody up, didn’t it? It was really exciting, people seemed to come out of nowhere, venues were packed and there was a real energy from the crowd. I’m very grateful that I was around at that time, and all that touring with Uncle Po prepared me for what was to come later, with Dexys, and gave me confidence. I would otherwise have been a bit nervous. I also learned a lot from the other guys in these bands, who were older and more experienced than I was.

JUSTIN LEWIS

So then in 1978, you enrol at the Birmingham School of Music. Suddenly you’re back in the classical world. What elements of the classical world do you think have helped you in the pop world, and vice versa?

HELEN O’HARA

From youth orchestras, I learned to work as part of a team, and to listen, but also to take directions from the conductor. I suppose Kevin in Dexys was like a conductor in many respects, with the ideas he was asking us to play. Because as you know, one piece of classical music can sound very different depending on who the conductor is. I’ve just finished making a playlist of all the music mentioned in my book – 209 pieces. What I found fascinating was deciding which version of a Beethoven symphony or violin sonata I should use. I went to Spotify and there are loads of different versions, so finding the ‘right one’ that touched me… It was extraordinary how different they all were, different tempos, different moods. And working with different conductors and different teachers as well also taught me about various approaches, to respect differences, and be open to trying things.

Also, in classical music, focusing on detail is absolutely crucial – dynamics, subtleties… and so when I came into the Dexys world, it really was like a pop equivalent of classical music in how they approached rehearsing. Incidentally, I did notice in college that a lot of classical musicians didn’t have a very good sense of rhythm. I remember in violin sections, people speeding up a lot, and finding that quite irritating. I think I probably had a pretty good sense of rhythm – drummers in Uncle Po and before them Gunner Cade helped to solidify that.

At the School of Music, I did feel different to the other students. I went in at 21, 22, and I hadn’t played with an orchestra for five years, and that’s quite a long time. I wasn’t feeling very confident, and I was aware of having to do a lot of work beforehand to catch up. I didn’t know what the standard was going to be like, so I was practising for hours and hours – I had this real fear I would be rubbish compared to everybody else. And I was fine, actually, but you don’t know that when you’re going into the unknown. And I hadn’t been reading music for four or five years – I’d been playing by ear. There were things that surprised me there – some musicians found it hard to do things like put chords to a melody. I thought everybody could do that, but obviously not!

I learned so much from other students, particularly one called Adrian, who I shared a desk with in my third year, who was the most beautiful player. I was really lucky going to Birmingham – it wasn’t too daunting. I don’t know whether I’d have got into the Royal Academy of Music or the Royal College of Music, but say I had, I think I would have found that quite intimidating, because they apparently had the best players, and the standard might have been so incredible. Birmingham, I felt I could fit in, the staff and students were lovely, so I’m really grateful about that.

JUSTIN LEWIS

And you felt you could be yourself?

HELEN O’HARA

I kept my past very secret, really, because I didn’t think anybody would get it. I really felt I had to be in the classical world to improve, and I didn’t want to be tempted back into pop music. I had made this decision to do three years of hard study.

JUSTIN LEWIS

In your final year, 1981/82, out of the blue, there was a knock on your door, and it was two guys from the Blue Ox Babes, the Birmingham band, and who had an affiliation with Dexys Midnight Runners. Did what happen next, in those two bands, come as a surprise to you? Because presumably you were thinking you might stay in the classical world?

HELEN O’HARA

I kept an open mind, but the reality of it was, by that post-graduate year, the fourth year, I hadn’t been playing or even listening to any pop music, and I knew I would have to try and earn a living through music. I didn’t want to teach, and so the obvious course was to get a job in an orchestra. That’s why I started doing auditions. I’d have probably been quite happy doing that, being the sort of musician I am. I would have probably tried to engineer situations where the music was interesting and stimulating. I was offered a job from the Bilbao Symphony Orchestra, and had I gone to Spain, it would have been great, I think. I’d have probably played a lot of Spanish music, learned Spanish, seen a bit of the country, and travelled through music. In that fourth year, I bought a Teach Yourself German book. That was my thinking: learn different languages, travel the world playing my violin.

But the Blue Ox Babes and then Dexys a little while later just blew everything out of the window. Because I am a pop musician. The music I mostly listen to is pop music. I absolutely love classical music and I go to classical concerts, but in my heart… if I had to choose… it would be pop music.

Sometimes I think you put yourself in situations where these things can happen, and the doors open, and you seize the moment and go with your gut feeling. Even if people are saying, ‘Don’t do that’, or ‘I’m not sure’, you listen to your heart and make a reasoned judgement.

JUSTIN LEWIS

And even if things don’t work out the way you expected, or how you wanted, you still learn something along the way.

HELEN O’HARA

Exactly, Justin, exactly. For instance, my first teacher at music college was a guy called Felix Kok [1924–2010] who was the leader of the City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra. A great teacher, and he offered me a gig with some members of the CBSO and other players, a freelance gig playing songs from films like Star Wars, at the Town Hall in Birmingham. I accepted. At the rehearsal, I realised I was way out of my depth. It was a three-hour rehearsal, sight-reading the music, and you might remember in those days, music for films and musicals were handwritten, not printed out – so it was very hard to read handwritten music for the first time.

JUSTIN LEWIS

I remember that very well!

HELEN O’HARA

After the rehearsal, I stayed on at my music stand to work on the music a bit more, and the conductor came over and said something like, ‘You could do with a bit more practice’. And it was such a horrible way he said it, but he was right, and that was a very hard lesson, but one that made me really think about what I should accept in the future. That is what the professional world was like with orchestras. I grew up a lot that day.

LAST: DEXYS MIDNIGHT RUNNERS & THE EMERALD EXPRESS: ‘Come On Eileen’ (Mercury/Phonogram, single, 1982)

HELEN O’HARA

Dexys’ record label at the time, Phonogram, was in New Bond Street, in London, and we’d get a bunch of copies of ‘Come On Eileen’ – but I would end up giving them away to friends or family. And then one day I realised I didn’t have any myself! Which I thought was a bit of a shame. I mean, I could have bought one on eBay, I suppose.

But one day, recently, I went into my local Oxfam shop in Greenwich, to buy a birthday card. On the way out, I saw this rack of albums and singles and for some reason – because I don’t do it normally – I flicked through them. And halfway through, there was the ‘Come On Eileen’ single sleeve staring at me. And I smiled, it just felt so amazing. I picked it up, it was in perfect condition. And it was weird, because you know, it’s 40 years on, and there’s also a remix of it out now as well. It felt magical. So, I’ve got my ‘Come On Eileen’ single back.

JUSTIN LEWIS

We’re so familiar with this song now, but I can distinctly remember when I first saw and heard it. It was on Top of the Pops, 15 July 1982, it was number 31 in the charts, and would soon be number one. I was already aware of Dexys from a previous few hits: ‘Geno’ and ‘Show Me’, although I somehow hadn’t heard ‘Celtic Soul Brothers’, your debut with the group.

But I had never heard ‘Come On Eileen’ and that Top of the Pops, in the best possible way, was a complete shock. Years later, one journalist wrote that ‘Come On Eileen’ had now joined the pantheon of songs – like ‘Good Vibrations’ and ‘Bohemian Rhapsody’ – that are so familiar you forget how unusual they are. Was there a moment when you thought, ‘This is it, then’?

HELEN O’HARA

When we got that first Top of the Pops, I think, the one you saw. Everything did happen very fast then, became a bit of a whirlwind. Yeah, it is an extraordinary record when you really start analysing it.

JUSTIN LEWIS

In terms of structure, especially.

HELEN O’HARA

The music is so orchestrated, cleverly written. The use of instruments… it could be a modern piece of classical music. Kevin is a genius, really, and Jim [Paterson] and Billy [Adams] and Mickey [Billingham], they wrote it too. But I don’t think any of us thought it was going to be a hit. We wanted it to be!

JUSTIN LEWIS

I know everyone says pop music was brilliant when they were twelve, but I was twelve in 1982, when some fairly leftfield records could become unexpected massive hits. Did you ever think of yourself as a pop star? Because to me, you were one.

HELEN O’HARA

You know, I never really thought of myself as a pop star. I was a musician in a band, that’s always what came first. I’ve always found the issue of clothes and image quite hard, and I was glad that Kevin took control of that.

JUSTIN LEWIS

It actually takes a lot of energy, that side of thinking.

HELEN O’HARA

It’s a huge amount of energy, and I admire people like Kevin and Roxy Music, who come up with these amazing clothes and outfits and things – it’s part of their art.

JUSTIN LEWIS

With pop, it is about the music, but with so many bands I’ve loved over the years, it’s also about the record sleeve and the band’s attitude, and so on. In the book, you mention how you kept sending back the Don’t Stand Me Down album sleeve again and again because it wasn’t quite right, and this kind of thing really does matter, I think. Because you’re making something that people are going to treasure.

HELEN O’HARA

Especially in those days, absolutely, Justin – because we were mainly buying albums then, as it was pre-CD. It’s like those covers the Stones did – the 3D cover of Their Satanic Majesties’ Request, or Sticky Fingers with the zip. But yes, it was great to be a part of a band where, as well as the music, all the visual aspects – the clothes, the artwork, the choreography – were very important. Equally, you can play music with somebody who says, just wear what you like – and that’s fine too.

JUSTIN LEWIS

Another thing with Dexys – the mythology. I remember the story that was ‘designed’ for you, that Kevin saw you at a bus stop in Birmingham holding your violin case, and he asked you to join the band. And I bought into that completely at the time.

HELEN O’HARA

Did you? Oh, that’s amazing. Brilliant.

JUSTIN LEWIS

And obviously it didn’t happen like that, although the way you joined the Blue Ox Babes the year before was pretty out of the blue. That there was a knock on the door and two guys asking if you’d like to join a band. It’s not what you expect.

HELEN O’HARA

With me resisting initially.

JUSTIN LEWIS

What did it feel like to be famous, so suddenly?

HELEN O’HARA

I found it very strange. When ‘Come On Eileen’ was number one, I was still living in my student flat in Birmingham, still getting the bus, and you find people talking about you and pointing at you. I felt extremely awkward in that situation.

JUSTIN LEWIS

Because what do you do?

HELEN O’HARA

Exactly. Really, all you can do is get out of where you are. It didn’t feel like a threat, but it’s a very different sort of attention to when people are at a concert, listening to you, even if they might be shouting or screaming or whatever… But when it’s ‘real life’ and you just popped out to get some milk… It wasn’t the kind of attention Kevin was getting, but the bits I did experience felt uncomfortable. And I felt it again much later, when my boys were at primary school and I was anonymous. I’d agreed to do this interview for a TV documentary [Young Guns Go for It: Dexys Midnight Runners, BBC2, 13/09/2000]. The next day I went into school, and people were bringing albums in [to be signed]. I was totally shocked they’d found out, and they were also beginning to treat me slightly differently and I just thought, I’m the same as I was yesterday.

JUSTIN LEWIS

It must be weird. There’s a version of you out there that is you, but it kind of isn’t you. It’s not even a distortion… it’s just that you were in that video, but that’s not the full, real you.

HELEN O’HARA

It’s one reason some people can’t cope and why they get out of this business, I suppose. But I liked that theatrical element that Kevin had created – the Emerald Express name for the string section, the fact we had all different names. It was a bit like being in a musical. It was just a slightly different character, but nothing too different.

JUSTIN LEWIS

People rather like stories like the bus stop story, because of that idea that anything could happen.

HELEN O’HARA

It’s quite romantic, isn’t it, as well. You can meet anyone at the bus stop.

JUSTIN LEWIS

In August this year, you were performing ‘Come On Eileen’ at the closing ceremony of the Commonwealth Games. What keeps it fresh, playing it, do you think? You’ve rearranged it a number of times now, right? It’s in a different key, for a start.

HELEN O’HARA

Yes, it’s a bit lower, when we did it in Birmingham, we took it down a few tones. ‘Eileen’ is incredibly high originally, something Kevin said he hadn’t considered when he first wrote it. He didn’t really consider the keys for his voice when he wrote anything in the old days, so to suit his voice now, we re-recorded the track. Kevin was the only one performing live, at the Commonwealth Games. I went into a studio to record the three violins for the track. And you know what, Justin? When I played, I felt like I was twentysomething again. When I came home, I sent a message to Kevin and to Pete Schwier, the engineer, telling them I just couldn’t help playing with the same energy and excitement that I felt when I originally recorded it. And it will always be like that. I was on a high after that concert for days afterwards.

What’s interesting is that Tanita Tikaram has changed a lot of her keys as well. Exactly like Kevin. They’re mostly lower keys but with one song, she’s moved it up a tone, interestingly.

JUSTIN LEWIS

We’ll talk a little bit more about Tanita in a moment, but I wanted to just ask you about Don’t Stand Me Down. And what becomes clear, reading about the making of that album, was despite the length of time it took to make – and obviously your relationship with Kevin ended during its making – it still sounds like there was an immensely harmonious working relationship with that record. And it was completely different to everything else in 1985.

HELEN O’HARA

I think a lot of people were probably not surprised that it was a bit different, but it was radically different. And the conversation thing, the talking, having a 12-minute song [‘This Is What She’s Like’]. We knew it was different, but it just felt right. We were so immensely proud of it, and still are. So when it came out, and didn’t get the reaction we’d hoped for, it was disappointing.

JUSTIN LEWIS

And you did a fair bit of promotion too for it. You were on Wogan, big live BBC1 show, 7 o’clock [13/09/1985. Fact! The other guests were Jackie Collins, Penelope Keith, Fascinating Aida and Kenneth Williams].

HELEN O’HARA

We played ‘Listen to This’ on Wogan, which in hindsight, perhaps should have been the single because it was three minutes, and a great song. I had to count it in to Kevin – I had a little earpiece – because it starts with Kevin singing before the band comes in. I had to give him a count-in, on live television. I remember thinking, I’ve got to get this right!

JUSTIN LEWIS

And am I right in saying that on Don’t Stand Me Down, you were Dexys’ musical director as well as their violinist? Can you outline what that role entailed?

HELEN O’HARA

Apart from co-writing some of the songs with Kevin and Billy [Adams], I would discuss the arrangements with them, and rehearse the band before Kevin came to rehearsals, to go through the basics of each song, to run through the parts and write out parts for musicians. Kevin didn’t have to be there all the time, he was often doing promotion, so the MD could often get a lot of the work done, fine-tuning things. It also meant that Kevin didn’t wear his voice out.

Often Billy and I auditioned musicians without Kevin being there. We had problems finding the right drummer for the album. We went to America, to Nashville at one point. After rehearsals, in the evenings, I would listen back to recordings I made that day and pick up on points where I thought we could improve the next day. And because it was a big band, with musicians from America, I would help to answer their queries. I took on a liaising role as well, between musicians and the management, which wasn’t my job, but that was fine. And then with live work, the MD’s job is to make sure everyone’s on it every night. Anything that wasn’t quite right the night before, you might rehearse in the next soundcheck. Kevin gave me a lot of responsibility and trusted me to look after the music.

JUSTIN LEWIS

And how did you start working with Tanita Tikaram, a few years later?

HELEN O’HARA

Paul Charles had been Dexys’ agent, and he had discovered Tanita at the Mean Fiddler, in Harlesden, a really great music club. After I left Dexys, he called me up to tell me he’d found this amazing singer/songwriter and they wanted violin on her single called ‘Good Tradition’. I was working on my own album project, and I wasn’t a session player as such, because you just didn’t do that with Dexys, but I thought, This does sound exciting. Paul sent me her demo and I really liked the song. So I agreed to the session. It was recorded at Rod Argent’s studio, he of Argent and the Zombies, who was producing it with Peter Van Hooke, the drummer from Mike and the Mechanics. I played my parts, made up a solo which they liked, and they liked all the other parts I’d written for it. From there, ‘Good Tradition’ became a hit, and then Tanita and Paul put a band together. I was with her for two to three years, and I played on her next two albums.

Then after the hiatus of my not playing for 20 odd years, and getting back with Dexys, Tanita asked me if I would be musical director and violinist for her Ancient Heart retrospective show at the Barbican. So it came back full circle. She’s great, it’s like when I work with Tim Burgess now. With both of them, when they walk into the room, the sun comes out. I can be myself when I work with them.

JUSTIN LEWIS

So why did you stop playing for 20 years? Was it a case of ‘all or nothing’?

HELEN O’HARA

There was an element of that. When I had my first son. I was still doing a little bit of playing in the first few months, for example with Graham Parker. And then, quite quickly, a few months later, I was pregnant with my second son, Billy, and I was exhausted. There were only 15 months between my two sons. I was tired, and work had been very intense for many years, but also, I just wanted to be home with them. I didn’t want anyone else looking after them or bringing them up. I didn’t want to tour and be apart from them for weeks on end. The other reason is that when I was in my 30s, I was beginning to feel a bit old being in a group, a weird thing to say now, but it’s how quite a lot of us felt at the time. Also, the violin is difficult, particularly if you’re not practising it a lot, and I felt every day I was losing more and more of my ability.

JUSTIN LEWIS

And what was the catalyst that made you go back to the violin?

HELEN O’HARA

Both my sons went to the Guildhall School of Music and Drama. My elder son Jack studied technical theatre and my younger son Billy was studying the drums. I was going to watch shows that they were involved in. Billy had been in bands at school, so I was seeing teenagers in bands again, which brought back memories, of course. So, I was missing it, but not really admitting it.

Then I went with Billy to see a Dexys show at the Barbican, for the One Day I’m Going to Soar album. It was great, but I felt like I could be back on stage because I knew all the old songs. It just made me think, I’m really missing this, my children are doing what I used to do. I heard a song before the gig, The Band’s ‘The Night They Drove Old Dixie Down’. Back at home, I put that CD on and that was the point when it got beyond my control; I got the violin out, and I sort of knew then that I was ready to embark on a slow journey back. But it also felt really exhilarating. I knew I’d be rubbish and I was rusty but, in my heart, I was still that musician. It was about muscle memory and confidence. I don’t regret stopping for a minute. Every second I was with my kids, I just really treasure that, and maybe – as you suggested earlier – I do compartmentalise stuff in my life. Maybe that’s just how I operate. I had been doing other things as well, part-time jobs – and studying a humanities degree for the Open University. That made me come out of my shell a bit more and meet people, as I’d lost confidence with people as well. It was a bit of a slow comeback, but I knew I’d be alright.

ANYTHING: PHILIP GLASS: Akhnaten: ‘Hymn to the Sun’ (Decca Gold/UMG, 2018)

Anthony Roth Costanzo, Jonathan Cohen, Les Violons du Roy

HELEN O’HARA

An opera singer I know was singing in the chorus of Akhenaten a few years ago. And she said, it’s really great, I can get you a cheaper ticket in a good seat. I didn’t know anything about it, but it sounded interesting. Within the first few minutes, I was just knocked out, I couldn’t believe this wash of sound. I was just mesmerised, under a spell. But also, this particular production used the Gandini Jugglers. They are part of the rhythm and they’re juggling in interesting ways, in time to the music. And then there are the costumes and the beautiful countertenor voice of Anthony Roth Costanzo. The opera hasn’t got any violins in it – it’s violas, cellos, double basses, so it’s this very dark, rich sound. That’s part of the incredible scoring. Anyway, it’s coming again, early 2023. I thoroughly recommend it, Justin, it’s at the Colosseum, English National Opera. The same production, with jugglers.

JUSTIN LEWIS

That sounds fantastic, I must make a note of that. And you’ve also selected ‘Belle’ by Al Green, and I believe this was a big influence on how you approached creating and writing Don’t Stand Me Down.

HELEN O’HARA

Yes, in 1983, when Kevin and I were going out together, he played me ‘Belle’ and some other Al Green songs, and I really started to understand the groove, and the sort of drummers that he was using, and that style of playing. There’s a lot of space in the music, and so when we were working on Don’t Stand Me Down, Kevin was saying, ‘Well this is the rhythm section we want, we want that style of drumming.’ It was a real eyeopener for me. I’d always been into drummers – Charlie Watts was one of my favourites, he’s not really an Al Green-type drummer, although he sort of is because he plays behind the beat. I think I had a natural disposition towards that sort of playing, rather than – say – heavy metal drummers which is not really my thing, much as I admire that style of playing.

So that’s how that came about. And then we were lucky enough to find Tim Dancy who had played with Al Green, when we saw them at the Royal Albert Hall [13/07/1984, with the London Community Gospel Choir]. I said to Kevin, ‘That’s our drummer’, and Tim came over, recorded a few songs with us, and did the tour as well.

JUSTIN LEWIS

What’s so clear throughout What’s She Like is you remain a fan. When you remember encounters or meetings with people or collaborations, whether it’s Willie Mitchell or Vincent Crane or Nicky Hopkins, your excitement and awe really comes over.

HELEN O’HARA

I still can’t believe that Nicky and I worked together. It’s almost like two lives. ‘Did I really play with him?’ I still pinch myself. Now I’m working with Tim Burgess! I’ve never taken it for granted. I still feel the same excitement I felt when I first heard ‘Get Off Of My Cloud’ in the sixties, and I hope it continues.

—

Helen’s memoir, What’s She Like, was published by Route on 1 October 2022.

You can access her related 209-song playlist on Spotify at https://open.spotify.com/playlist/55tJslj4iEEvdX2X4hIgcz?si=0b9498e1cc804c8a

To mark the 40th anniversary of Dexys Midnight Runners’ Too-Rye-Ay, a remixed version of the album, subtitled As It Should Have Sounded, was released by Mercury Records on 14 October 2022.

Helen continues to collaborate, on record and live, with both Tim Burgess and Tanita Tikaram.

You can follow Helen on Twitter at @oharaviolin, and on Bluesky at @oharaviolin.bsky.com.

FLA PLAYLIST 15

Helen O’Hara

(For the time being, this site and project uses Spotify for the conversation playlists, but obviously I disapprove that Spotify doesn’t pay artists and composers properly, and other streaming platforms are available, as are sites to buy downloads and buy recordings. For consistency, you can also listen to the selections via YouTube (where available), and links are provided in each case, below.)

Track 1: PYOTR ILYICH TCHAIKOVSKY: Piano Concerto No. 1 in B-Flat Minor, Op. 23:

Allegro non troppo e molto maestoso

Van Cliburn/Kirill Kondrashin: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=frxZjSG8lMs

Track 2: PJ PROBY: ‘Maria’: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OX1wDV3ENF8

Track 3: FRANZ SCHUBERT: String Quartet No. 14 in D Minor, D 810:

‘Death and the Maiden’: I. Allegro

Endellion String Quartet: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CNULkV5lyHE

Track 4: BOB AND MARCIA: ‘To Be Young Gifted and Black’: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yscozSAumgs

Track 5: DEXYS MIDNIGHT RUNNERS: ‘Let’s Get This Straight from the Start’: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BqJlhXcW8X4

Track 6: SLADE: ‘Coz I Luv You’: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ONQPB9HTP5c

Track 7: MOTHERS OF INVENTION: ‘Directly From My Heart to You’: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KB3HdC-Iums

Track 8: UNCLE PO: ‘Screw My Friends’ – Demo: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GGNeg0beo4s

Track 9: BLUE OX BABES: ‘Walking on the Line’ – 1981 Demo: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XFkDGkyLZQI

Track 10: DEXYS MIDNIGHT RUNNERS AND THE EMERALD EXPRESS: ‘Come On Eileen’: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6BODDyZRF6A

Track 11: DEXYS MIDNIGHT RUNNERS: ‘Listen to This’: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1fRW4g52a7w

Track 12: TANITA TIKARAM: ‘Good Tradition’: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SAbgrq4TPT8

Track 13: TANITA TIKARAM: ‘Thursday’s Child’: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3RRCXqO8i9M

Track 14: THE BAND: ‘The Night They Drove Old Dixie Down’: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=w69ZVHpjYAk

Track 15: PHILIP GLASS: Akhnaten: ‘Hymn to the Sun’

Anthony Roth Costanzo/Jonathan Cohen/Les Violons du Roy: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=s8dEk1KXu0g

Track 16: AL GREEN: ‘Belle’: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kjEHoz1r3bs

Track 17: DEXYS MIDNIGHT RUNNERS: ‘Old’ (As It Should Have Sounded 2022): https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UtWtJbelz7o

Track 18: DEXYS MIDNIGHT RUNNERS: ‘This is What She’s Like’: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=o94-YJlyCa4