Of all the guests I’ve had on First Last Anything so far, Kent-born Joanna Wyld might have worn the most musical hats. Writer, musician, composer, librettist, teacher and administrator, she’s played in orchestras, concert bands and pop groups, she has a passion for everything from bellringing to soul music, and has been a prolific writer of articles, liner notes and concert programme notes for many years. Her writing is always so perceptive, thoughtful, colourful, nuanced and (underrated quality, this) informative.

In conversation, Joanna is no different. What follows, the highlights from a couple of hours on Zoom one afternoon in October 2025, could easily have run twice as long. I love it when a conversation with a guest introduces me to many new pieces, and this is certainly one of those occasions. We both hope you enjoy reading it, and sampling Joanna’s wide-ranging listening choices – not only her First, Last and wildcard selections, but all her other suggestions too.

—-

JUSTIN LEWIS:

So to begin with, what music do you first remember hearing in your home? Because I know you have a very eclectic taste – was that always there?

JOANNA WYLD:

Yes, I think ‘eclectic’ is a really good reflection of my home growing up. I didn’t grow up in what you would describe as a musical household. Everyone loved music, but my parents weren’t classically trained – my dad can’t read music but loves it, my mum can read music, and plays the piano and the organ.

We were never told that a particular genre was better than others. We had a good eclectic range of records that we enjoyed playing. I think the first record I learned to put on the record player independently was The Beatles’ ‘I Want to Hold Your Hand’. And there were quite a few Beatles singles, but also my brothers and I would use music to capture our imaginations a bit. Because we’d hear ‘Oxygene’ by Jean-Michel Jarre when we’d go to the London Planetarium, it would be on if you were waiting to go in. So [at home] we’d use those kinds of experiences – we’d use a reel-to-reel tape recorder, and – I mean, we were very little, it was very silly – we’d write a type of sci-fi script with ‘Oxygene’ playing in the background as our soundtrack.

My relationship with sound was affected by certain things growing up. My grandad and my dad were – and my dad still is – bellringers, which I think is a hugely underrated discipline. We rightly praise the Aurora Orchestra playing things by heart – I went to see them do The Rite of Spring by heart [at Saffron Hall in 2023] and it was absolutely mindblowing, they deserve all the credit for that – but bellringers do that every weekend, three hours or more of memorised mathematical permutations while handling these unwieldly bells. If we’re going to be patriotic about something, I feel like that’s something to be proud about, because it’s unusual and it’s such a skill.

With bellringing, there are these interesting patterns, but also these slight irregularities because it’s not mechanised – there are people doing this, and there are also these spatial qualities of sound that you get when you hear it resonating in a ringing chamber. With the tunings, you get these harmonics, these overtones, and sometimes they seem to vibrate or clash.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

There’s that way that bells can sound slightly off-key, which you sometimes get with distance and echo. Do you have perfect pitch, then?

JOANNA WYLD:

No, and actually, I suspect my relationship with tuning is a little bit strange because I grew up with this sense of music being a little more fluid, not necessarily fitting within these strict parameters we’re used to thinking about in terms of pitch. And I suspect that then influenced my love for composition and contemporary and 20th century music later, made me open to it, because I’d grown up with this variety of sounds, without that sense of hierarchy about it.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

And did you do some bellringing yourself?

JOANNA WYLD:

I did learn for a short while, but then I had an experience where a rope hit me – it is quite dangerous. My dad was there, and he grabbed it and it was fine… but I was a bit put off by that. Also, I don’t think I’ve got the mathematical brain to do all the actual methods, but I love the sound of it. It could almost be rebranded as mindfulness. If you listen, it’s got enough patterns to keep your brain interested – but it’s also quite mesmerising. I think, I hope, there is a new generation of people coming through who can do it. It’s in the category of things like dry-stone walling… almost like folk traditions. These things deserve to be continued in the least jingoistic way, just because they are interesting and skilful.

I have a CD called Church Bells of England, which is an incredibly sexy thing to own, and it has all these examples of ringing in various places. None of them are perfect in terms of the ringing or the sound quality, but they give a sense of what’s hypnotic about it. The example from St Giles, Cripplegate launches straight into these complex patterns, it’s so absorbing. And then you have composers who’ve drawn on this, from William Byrd’s emulation of change-ringing in keyboard music, to Jonathan Harvey’s wonderful Mortuous Plango, Vivos Voco, which samples the tenor bell at Winchester Cathedral. I heard it played during a London Sinfonietta concert and you felt like you were surrounded by the recording of the bell, it was a visceral experience.

——

JOANNA WYLD:

Classical music came in when we were in the car, we’d put cassettes on, and I did discover then that I really loved this music. This would have been from the age of about eight onwards… that’s when I started to play the flute.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

The exact age I started too, actually. Why did you pick the flute, then?

JOANNA WYLD:

Well, it was slightly by default, because in my primary school, which was very tiny, you could learn the piano, the violin or the flute. There were three teachers who came in, and I had more of a yearning to learn the clarinet, but it wasn’t really possible. It just wasn’t very practical – this is before we got our piano. My older brother had been learning to play the violin, so I kind of ended up on the flute because that was what was available. I mean, it took ages to get a note out of it, but it wasn’t a burning ambition to learn that particular instrument.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

Yeah, I think I wanted to play the violin, but I have a feeling my parents couldn’t have coped with the idea there’d be at least three years of scraping. I seem to remember we were watching something on TV, there was someone playing the violin absolutely brilliantly, and I recall saying something like, ‘Oh I’d love to be able to do that’, and it all went very quiet in the room. So maybe that was a clue. I think with the flute, I think I liked it as a colour in an ensemble, rather than as a solo instrument. I did enjoy playing but I found solo playing quite stressful – and also I felt a bit alienated in my teens because I did want to be in bands, but I had no idea how you went about that. I learned the saxophone for a while, and that got me into bands a bit. But I told this story on a podcast recently – when I got into university, I did a music degree for a year, but obviously in the college orchestra you could only really have three flautists in there. You couldn’t really have fifteen.

JOANNA WYLD:

Yes, if you’ve got too many flutes, what do you do? I was really lucky because I grew up near the Bromley Youth Music Trust, a music hub that offers affordable music ensembles, so I grew up in a concert band system, and that’s how they deal with instruments where there are too many for a standard orchestra. That was quite a discipline in terms of ensemble playing. And so I ended up in this concert band where we’d tour and do competitions and it was quite high level, but it was a brilliant exercise in eclectic music, because in concerts you’d have stuff written for it specifically, often quite contemporary and imaginative. And then you’ve got arrangements of pop, film and classical – so a lovely kind of cross section. Music for concert band and brass band is another genre that’s oddly underrated I think. I love the ‘Overture’ from Björk’s Selma Songs (don’t watch Dancer in the Dark, it’s traumatising, but listen to the soundtrack), it’s a lovely example of rich brass writing. And the song that pairs with it, ‘New World’, is gorgeous, very powerful.

And then in the sixth form, I got into the BYMT symphony orchestra having sort of worked my way through. That was a huge experience, and I was just so lucky, because we were playing quite high-level repertoire: Britten’s ‘Four Sea Interludes’, and Bernstein’s ‘On the Waterfront’, and Dvořák symphonies, Sibelius symphonies… We played Mahler, you know! I became immersed in all this. And our teachers were phenomenal because they expected these really high standards of us, and we were living up to them. This was a lot of state-school educated people, and we were so lucky to have this affordable opportunity to make music like that. Then at university, I was exposed to more 20th century and contemporary and started to play things like the Berio ‘Sequenza’ and Messiaen’s ‘Le merle noir’, stuff which uses more kind of percussive and unusual sounds on the flute.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

Tell me about Richard Strauss, who you mentioned to me was a particularly important composer you heard at a formative age.

JOANNA WYLD:

It’s his ‘Four Last Songs’ [composed in 1948] in particular. I think, for GCSE or A level music, I had heard his ‘Morgen!’ [‘Tomorrow!’]. Back in the day, CDs were quite expensive and I wasn’t buying them lots. My birthday or Christmas was coming up and so I asked my parents for Strauss’s ‘Morgen!’. They couldn’t find that on record in our local record shop so they gave me this instead – a happy accident.

I love all of the music on that record for different reasons – you’ve also got ‘Death and Transfiguration’, [a tone poem written in 1888–89] when Strauss was quite a young man, and which in many ways is not really about death but is more life-affirming, though it’s dramatic. Whereas with the ‘Four Last Songs’ everything’s stripped back, because he did tend towards bombast and vulgarity at times, and these were written when he was really facing death. They’re just four of the most beautiful things ever written. The third one in particular [‘When Falling Asleep’] just has this incredible climactic moment and wonderful violin solo. And in the final song [‘At Sunset’], you get this pair of piccolos which are the birds representing the two souls of him and his wife, off into the ether – it’s just so beautiful.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

And ‘At Sunset’ quotes a little motif from ‘Death and Transfiguration’, doesn’t it, at one point?

JOANNA WYLD:

Yes, and there’s a horn solo at the end of [the second song] ‘September’ – his father was a very celebrated horn player. And through him, he’d been to hear lots of premieres of Wagner operas because his father was playing in them, and his father tried to discourage his interest in Wagner! [laughs] Anyway, so you feel as though that horn solo might have been just a nice little valedictory kind of farewell to that memory of his father as well.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

I know you particularly love this specific recording of the ‘Four Last Songs’, with Gundula Janowitz singing and Herbert von Karajan conducting [first released in 1974], but I take it you know who else was a fan of it as well?

JOANNA WYLD:

David Bowie [which inspired him to write four songs for his Heathen album]. Yes, I love this fact. I’m kind of thrilled that it’s that specific recording, with Janowitz – because people are divided as to which is the best. Strauss is one of those people, like Mahler, where I have different recordings of their works because I do think people can bring something different in. But yeah, I just love the fact that Bowie loved the same recording as I do!

JUSTIN LEWIS:

Bowie’s influences just seem to come from so many places. We’re back to eclectic again, as with you.

JOANNA WYLD:

I think I’m discerning about quality, but there isn’t a hierarchy of genres. Obviously, classical is my speciality, and I’m passionate about it, but it’s all there to be enjoyed, we’re complex human beings, and Bowie obviously recognised that. I understand why people specialise, but I love to embrace variety.

——

FIRST: QUEEN: ‘Bohemian Rhapsody’/ ‘These Are the Days of Our Lives’ (EMI Records, cassette single, 1991)

JUSTIN LEWIS:

‘Bohemian Rhapsody’ was first released in 1975 when I was five, and I vividly remember the video on Top of the Pops. It’s hard to remember what the world was like before this record, because it is one of the first that’s seared into my mind.

JOANNA WYLD:

And this reissue was the first record that I can remember wanting to buy. I was eleven. I heard it on the radio. It was just unlike anything else I’d ever heard. But it’s got that context of originally coming out in the mid-seventies when there was the mainstream three-minute pop song and at the same time there was prog: people yodelling or a synth solo, sometimes quite self-indulgent. But here you’ve got something that’s both: it’s mainstream adjacent and also proggy – it’s an extended idea and a concept. I just thought it was really fun, kind of dramatic and extraordinary. And that appealed.

It wasn’t that long afterwards that Wayne’s World (1992) cemented it as well. But for me it also represents a couple of things I generally find interesting about music. One: it’s the victim of its own success – as you said, you can’t imagine it not being there. Even those who don’t like it, couldn’t imagine it not being there. That’s an extraordinary achievement. And that can lead to it becoming ubiquitous and taken for granted, almost an irritant.

A parallel for me would be Holst’s Planets suite. I fell into the same trap with that – I’d just heard it so many times. And then at university, I finally got to play in it. And I realised: this is so well written, so well orchestrated, and this would have been incredibly original at the time. And it has been emulated a lot since, but I hadn’t given it enough credit for what it was, when it was written.

The other aspect of ‘Bohemian Rhapsody’ I find interesting: it’s so of the person who wrote it. Some composers have that instantly recognisable fingerprint. Holst is one, Messiaen, Stravinsky, Copland, more recently Louis Cole and Genevieve Artadi, both separately and together as Knower, – and I think Freddie Mercury is another, in this song. It’s him, just going, ‘I’m not going to worry about what anyone else thinks, I’m not going to draw on lots of other influences, this is what I want to write.’ I admire anyone who can do that.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

There are aspects of it that remain mysterious, like nobody has ever quite nailed what it is really about. Brilliantly, someone has put up clips of Kenny Everett actually playing ‘Bohemian Rhapsody’ for the first time, on his weekend lunchtime show on Capital Radio in 1975 – have you heard this?

JOANNA WYLD:

No, but he championed it, didn’t he? I haven’t done a deep dive, I have to admit.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

I only found it the other day. Seems he had been playing extracts from it, and then he plays the whole thing.

Kenny Everett, Capital Radio, c. October 1975

We had this song in our house because it’s on their album A Night at the Opera, which has this ambitious mix of quite whimsical, almost music-hall songs, and then out-and-out rock tracks. I still think it’s probably their best record. I like to hear it as part of the album. As you just said with The Planets, it’s good to go back and play it in context.

But even with Kenny Everett’s support, it’s still really weird they put this out as the single, in a way. And obviously, you bought this re-release after Freddie Mercury had just died [24 November 1991]. How aware were you of that event?

JOANNA WYLD:

I think this was the first experience I had of a celebrity death having an impact, and of feeling incredibly sad. The AA side, ‘These Are the Days of Our Lives’, is just incredibly poignant. I can’t watch the video where he sort of says ‘I love you’ at the end. It’s just so, so heartbreaking. I think for a lot of people, it really brought home the reality of the HIV and AIDS pandemic. That this wonderful larger-than-life figure, famous and well-off and all the rest of it, had been hit by it. I don’t remember the extent to which I understood everything at that point in my life, but it definitely stayed with me. It felt like such a horrible shock and a horrible loss.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

Until I was doing the research for this, I’d forgotten it was a charity single, for the Terrence Higgins Trust. Since when it’s been in so many other things – Wayne’s World as you mentioned, but just this summer, in September, at the Last Night of the Proms.

JOANNA WYLD:

The Prom was a lot of fun. I know it divided opinion a little bit, but it’s nice to celebrate people while they’re alive. I think Brian May and Roger Taylor deserve that moment. While I’m not the biggest Queen fan, and I don’t listen to the music loads, they do all seem fundamentally decent, and those remaining members have really championed Freddie’s memory and always mention him. There’s something quite loving there.

——

JUSTIN LEWIS:

I wanted to talk to you about writing liner notes for CD releases and programme notes for concerts, because that’s something you’ve been doing for many years. How did you first get into this sort of work?

JOANNA WYLD:

The first clue lies back in my childhood. We’d play classical music in the car, and one cassette we had was Saint-Saëns’ Carnival of the Animals suite [composed 1886, but only published posthumously in 1922], featuring lots of quite kid-friendly stuff. And when I went to secondary school, my first music assignment was to write the description of a piece of music. I remember spending ages on this, being so enthused by it. I went home, read the sleevenotes of Carnival of the Animals, got my little dictionary of music, did a bit of research and wrote it up. It was like a prototype for what I’d do later. It was just a Year 7 essay, I was about eleven, it wasn’t hugely in-depth, but it’s interesting that’s stuck with me as a memory – an early enjoyment of writing about music showed up.

But how I got into it professionally… I was working at a record company, originally called ASV, which also had some peripheral labels: Gaudeamus was an early music label, Black Box was a contemporary music label, everything on White Line was sort of middle of the road, like light music, and then Living Era was the nostalgia label. This was my first job after university, and I was the editorial assistant.

For Living Era, we used to get these liner notes written on a typewriter by these lovely old gents who were jazz experts, some of them virtually contemporary with the songs they were writing about! They were delightful to work with, but one day we were missing a liner note, and my boss said, ‘This person just forgot to file this copy and we really need it now. Can you cobble something together?’ And this was in the days before there was a huge amount on the Internet about these things. I think I used early Wikipedia. But because I’d edited and proofread so many of these notes already, I knew the style. So I was able to emulate that slightly chatty nostalgic style, as well as getting the information in. I knocked this out quite quickly and my boss was quite impressed, which was nice, and then asked me to do more and more bits of writing.

And then ASV got bought out by Sanctuary Records, which had all these associated metal artists – so you’d go into the canteen and Bruce Dickinson of Iron Maiden would be there, and they’d have Kerrang! TV on. We had a meeting interrupted because Robert Plant was in reception. It was very glamorous, quite fun – I loved it, and I got to meet some really interesting people.

But all this meant that later, still in the heyday of CD production, particularly in classical music, I was hired to do a lot of freelance writing. There was a lot of repackaging – essentially getting older recordings and repackaging them as ‘The Best of Poulenc’ or whoever it was – and new labels were being set up. So I was asked to churn out quite a lot of essays for them, and quite quickly built up a body of work. The hardest commission was when my daughter was only a couple of months old, when I was asked to do 17 liner notes in two and a half weeks, so I was a machine for that period. It was something like one essay a day. And obviously I was looking after a small child!

Then I started to get emails from various people – the BBC, Royal Liverpool Philharmonic, and others: ‘We’ve noticed your writing, we like it, would you like to send me some examples.’ And it’s slowly built from there.

I would say I’m a generalist. I’m not someone who’s done a PhD in a specific area, I always treat myself as someone who’s not really an expert, but I will do the research when I’m writing a programme note, as thoroughly as possible, as is relevant for that programme note, but I’m always kind of standing on the shoulders of people who’ve done that in-depth research. But equally, I’m trying to bring my perspective, and the way I hear it and write about it, hopefully I can bring some joy to people’s listening experience.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

And you got to write about new commissions as well, is that right?

JOANNA WYLD:

One that was really nice – it was a premiere performance – was Mark-Anthony Turnage’s ‘Owl Songs’ as a tribute to Oliver Knussen (1952–2018). It was a real privilege to write about that because I’d met Oliver Knussen a couple of times, an absolute gem of a man and composer. His music is just these crystalline jewels of orchestral beauty, and I’d recommend something like ‘Flourish with Fireworks’ (1988) to anyone who thinks contemporary music’s a bit alienating. So he mentored Mark-Anthony Turnage who I’ve also since interviewed, and Olly was known affectionately as Big Owl – particularly Mark referred to him in that affectionate way. So the Owl Songs are these wonderful tributes.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

Are you adhering to house style with these things, or do they tend to leave you alone?

JOANNA WYLD:

There’s very little editorial interference, actually, which is lovely. And I’ve built up trust with a number of commissioners, which is great. What has changed in the style of writing for these sorts of things is it used to be much more academic, much closer to my university essays. The expectation would be that your audience would be aficionados – but it was a lot drier. Actually it’s much more fun now, because the emphasis is on something more inviting and accessible that could be read by anyone, and if you do something more technical, you just explain it in passing. You try and make it as enjoyable as possible to read and that has been fun because I can bring out my own personality a bit more, and feel freer to illuminate what’s exciting about the music.

I feel very strongly that we tend to present classical music as very polite, elegant and smooth, and it can be all of those things, but it can also be… terrifying, for example. Like with Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring, I get palpitations – it’s visceral, it’s filthy. Or Richard Strauss, which can be, to be blunt, very sexual – and I think people almost need permission to hear it in that way because they think classical is ‘all very nice’, and actually… he was a bit of a perv, you know? And if that sort of thing’s there, it’s pointless to not draw people towards that way of listening or bringing out the enjoyment of it.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

Why do you think then that happened to classical music, that the politeness of it became paramount? Is it because of how it was taught, or presented?

JOANNA WYLD:

Every possible experience you have had is all there in classical music somewhere. These are very complex people writing it, and often that’s what I enjoy exploring – their personality, their quirks, their flaws, and the rest of it.

I mean, this is a huge topic – people have done PhDs on this – but in terms of how we receive it… the Victorians have a fair bit to answer for. You know, the idea of the Opera House: people had previously been there as an everyday experience, and then it became this hierarchy of ‘who sits where’, and then obviously with different genres, you have this shift – music that was contemporary becoming historical, and then becoming classical, so it’s no longer immediate. Whereas pop music is obviously reflecting people now. So with anything historical, you can end up with this sheen of respectability and this sense of it being a museum piece, something that you have to treat with reverence.

It’s really complicated but yes, definitely the way it’s taught, even the way it’s marketed… the way even people who love classical music sometimes talk about it… it can be quite reverential, and there are bits of it that are of course sublime. But there’s plenty else in there, and it’s almost just encouraging people to go and hear it.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

So how do you strike a balance between musicology and biography when you’re writing these?

JOANNA WYLD:

There used to be more of an emphasis on musicology – perhaps the structure of a piece of music could go into a bit of detail – whereas now I tend to start with biography and history and set the scene. I try and give a bit of historical context and wherever possible bring out the interesting details about that composer that are relevant to that piece. And if possible, quotes – direct quotes are really interesting. If I can find them, if they’re reliable, just from letters or whatever, because that just tells you so much about them.

We were told at university: You mustn’t let the biography of a composer influence the way the music is interpreted too heavily. I think that’s fair, particularly from an academic perspective – that you are not there to try and tell a story through every single score. And if you’re trying to look at it on its own terms, musically, you do need to separate the two, but for a concert-going or a CD-listening experience, it brings the music to life, stops it being a museum piece. Because you realise these human beings were just as complicated as we are, and often just funny, or grumpy or whatever. Then I might go into some musical detail, and if I’ve got space, try and do a bit of a listening guide, try and draw out some highlights, some things to listen out for.

Occasionally I’ll do a deep dive, find something that isn’t widely known, or almost gives people permission to think of those composers in a slightly different way. For example, JS Bach’s ‘Musical Offering’ (1747). With Bach, he’s so revered we tend to deify him, and talk about him in reverential tones. But the story behind that piece is so fascinating. I did a lot of research from a non-classical perspective, like reading a bit of Gödel, Escher, Bach [by the US scientist Douglas Hofstadter, published 1979], and stuff about mathematical patterns. But with that piece, you also had family dynamics going on – his son [CPE Bach] was working for Frederick [the Great, King Frederick II of Prussia] who commissioned this piece, but they laid down the gauntlet in the most provocative way by saying, ‘Oh, improvise a fugue in six parts’ and no-one had ever really done that. He managed a three-part improvisation and then went away – and it was as though he had a fit of pique, producing this ridiculously vast response to this challenge, creating something out of this deliberately difficult and angular theme. And none of this that I included was new, but it was quite nice to bring out those aspects. Especially with someone like Bach who obviously had great faith and appears to be very holy… that composition came from a bit of anger and irritation.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

Yes, bringing composers to life as human beings without overemphasising to the detriment of the work. I’m sure it’s changed in school-teaching now, back stories are brought up more. I had good music teachers at school, but I don’t ever remember being taught about these composers’ lives, which now feels really weird. Or even the wider history of the time.

JOANNA WYLD:

It’s like Beethoven was a young carer, effectively. His dad descended into alcoholism after his mother’s death, so he was caring for his siblings, which prevented him from staying in Vienna to study with Mozart, which he really wanted to do. Information like that is really humanising, especially as Beethoven was perhaps the first in the 19th century to be regarded as ‘in touch with the divine’, and really cast that long shadow.

I would probably say I’m not a musicologist like, say, Leah Broad [FLA 28], but I’d call myself a music historian. The history of it is fascinating, and it helps people to get closer to the music because they realise these were normal people who might have been incredibly gifted but also worked really hard. Again, Bach was one of those people, who said, Anyone who works as hard as me can do the same thing. Which is not entirely true, but nor was he sitting there on a cloud, you know, being a genius.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

I mentioned this in the Leah Broad chat, about hearing Radio 3 say in passing about how Felix Mendelssohn essentially revived JS Bach’s music around 1830 – it had hardly been played for about eighty years after Bach’s death.

JOANNA WYLD:

It had really gone out of fashion, it’s sort of staggering. Although Mozart and Beethoven had studied Bach, and actually the sort of contrapuntal depth they learnt from him is one thing that elevates their music above the more lightweight stuff of the time. So his influence was still there at key moments, although in terms of performance it wasn’t until Mendelssohn revived it.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

Something else I discovered from your website: you’ve been a librettist. Can you tell me about your work with Robert Hugill?

JOANNA WYLD:

That was a wonderful opportunity. A friend put us in touch. It was called ‘The Gardeners’. Robert had read this article about a family of gardeners in the Middle East, tending war graves, and it was intergenerational. So he had this idea, it was his conception, of how the generations relate to each other, and the old man of the three generations could hear the dead. So there was that metaphysical aspect to it, and so we had a chorus of the dead, and the youngest is quite a rebellious character. All of this was fictionalised – this isn’t based on the article – and it was a chamber opera, so it’s not huge scale, but it unfolded as a sort of family drama. Ultimately, the old man dies, whereupon the youngest man inherits his ability to hear the dead. Meantime, you’ve got the women of the family trying to keep the peace. So it’s a family drama with a metaphysical aspect. We performed it a couple of times, which was amazing, firstly at the Conway Hall and then at the Garden Museum with a wonderful cast.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

Is it about trying to find words that sound good as well as have meaning? When you’re writing something like that, does it become clear what doesn’t belong? Do you have a working method for something like that?

JOANNA WYLD:

I definitely think it helps that my Masters was in Composition. And I’ve set a lot of words myself. So I know the kind of thing I would set, and it’s not always the choice you might expect. It has to be something where the words lend themselves to musical treatment. Which often means there’s a rhythmic lilt to them – you’re thinking of the words rhythmically, but also making sure they don’t obstruct the music. So if it’s really overly polysyllabic and flowery, that’s going to get in the way, and it becomes about the words, not the music. But there’s also how the words sit next to each other – I remember reading a wonderful letter from Ted Hughes to Sylvia Plath about the choice of two words in one of her poems. It was two quite punchy words next to each other, and I think he suggested weighting them differently but also talking about them as if they were physical objects. I relate to that. So when I’m writing something like that, and I’m not saying it’s on that level, I try and think in terms of the weight of the words, and how they’ll then sit in someone’s mouth.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

Because just as there’s a musicality in music itself, there’s a musicality in words too, so you’ve got to match the two up. Do you still write music yourself, as well?

JOANNA WYLD:

I’ve written a couple of songs with bands I’ve been in, I enjoyed that. I had a really lovely teacher at university, Robert Saxton, but you really have to pursue it, you have to be so obsessed with it, and I also realised I’m probably better at writing about music than writing music.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

What sort of music were you writing for the bands you’ve been in?

JOANNA WYLD:

One song started out as a sort of Hot Chip parody really, almost like a joke – and then I added some influences from LCD Soundsystem; it’s quite a fun track, which we once played at a wedding, and a conga formed, which was one of the biggest compliments.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

That’s brilliant.

JOANNA WYLD:

And then I’ve written a sort of cathartic song called ‘Prufrock’, where I drew on TS Eliot’s ‘Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock’.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

So you were singing these?

JOANNA WYLD:

Yeah. Another one was called ‘The Air’ which was my attempt at layering stuff together in a sort of Brian Wilson fashion.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

And what were your bands called? Were you gigging?

JOANNA WYLD:

One was called Fake Teak, and we recorded ‘Prufrock’. It’s my brother’s band, named after the equipment that our dad had when we were growing up. That’s now evolved into something called Music Research Unit, which is a similar line-up, but more fluid and with new songs. We had our first rehearsal just yesterday! Then I’m in another band called Dawn of the Squid, and I don’t write for them, and they’re hard to describe, but they’re kind of… indie-folk, and there’s comedy in there.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

Is this out there to hear?

JOANNA WYLD:

There’s a new Dawn of the Squid album, which I didn’t play on, I can’t take any credit, but that’s out. There’s quite a bit of Fake Teak on Spotify. I play synthesisers and flute in these groups, and to go back to what we were discussing earlier – about sounds not being strictly in tune – what I find lovely about some synthesisers is they feel much closer to acoustic instruments; they can go out of tune, and you can make unpleasant as well as pleasant noises on them. I play this instrument sometimes called an ARP Odyssey [analogue synthesiser introduced in 1972] and it can go out of tune on stage, it’s a real rarity, and it’s been used in loads of pop like Ultravox. But I have had gigs where it’s gone a bit out of tune, and in a weird way I kind of enjoyed that more than digital instruments where it’s got presets and everything’s tidy, because it feels much closer to my experience of other instruments.

LAST: THE UNTHANKS: Diversions, Vol. 4: The Songs and Poems of Molly Drake (2017, RabbleRouser Music)

Extract: ‘What Can a Song Do to You?’

JOANNA WYLD:

I’m not a folk expert, I’m getting into it more, but like a lot of people, I came to this because I heard Unthanks do the ‘Magpie’ song on Detectorists. Then I went to a concert, locally, on the strength of that, and that’s where they performed some of these Molly Drake songs. I loved the whole concert – one of my prevailing memories of it is my crying my contact lens out during one of the Molly Drake songs, and just having to sit there with it in my palm, kind of half-blind.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

These songs are amazing to hear because we know so much, or at least we think we do, about Nick Drake’s life, but obviously the Molly Drake archive hasn’t been pored over by scholars too much. I think most of these songs are from the Fifties, and the Unthanks have covered them, apparently, because they wanted to make better quality recordings. And the Molly Drake versions are out there too. But there’s something about these songs that are both public creativity – as in the Drake family being aware of these songs – and private creativity too as it wasn’t out in the public domain for years. And you keep having to remind yourself that these songs were written before Nick Drake got into music himself, not afterwards.

JOANNA WYLD:

Yes, so many women composers are talked of in relation to their male relative, but you’re right that she was doing this first. It clearly influenced Nick Drake, and the almost painful shyness is a clear link, so it illuminates his music, which I also love, but I think on its own terms Molly’s music is phenomenal and yet, incredible that she was so shy that I think her husband bought her a reel-to-reel and set her up in a room on her own with it. He recognised her talent so there was this idea of ‘Let’s get this down for posterity’, but there was no concept in her mind that anyone would ever hear it, which seems really alien to us now, but there’s a real beauty to that.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

I think there can be a pressure when you’re writing something that you know is going to be for public consumption in some way. But I found a great Rachel Unthank quote:

‘Her work shares her son’s dark introspection, but in Molly we get a clearer sense of how those who understand depths of despair can do so only by understanding happiness and joy too. Through Molly’s work, we see the soulful, enigmatic lonesomeness as a person who is also a member of a loving and fun-loving family.’

I think that’s really important because Nick Drake – and his work – tends to be defined by what happened to him, and not all of him and his work is like that. I mean, the Molly song that feels like it could have been written in response to his early death – ‘Do You Ever Remember?’ – was written much earlier.

JOANNA WYLD:

You mentioned family, but obviously on the Unthanks recording, you’ve also got Gabrielle Drake reciting the poetry. I went to the Nick Drake Prom, with the Unthanks performing with Gabrielle Drake, which was phenomenally moving – and brave of her as well, I thought. And it’s a rich combination to listen to – you’ve got the sugared almond sound of the Unthanks’ voices, and the woodier timbre of her delivery. The whole thing really cuts to your heart, similar to Nick Drake, but it’s even less crowded in metaphor, it cuts to the heart with a deceptive simplicity. The first track, ‘What Can a Song Do to You?’, has one of those melodies that feels like it’s always existed, and then this tremendous bit of poetry. I really admire people who can pick and use very few words to convey something. I was lucky enough to interview Michael Morpurgo many years ago, and he blew my mind in terms of how to write. He used to say, ‘We don’t need to teach kids lots of florid words, but to be direct.’ That lyrical and nuanced but straightforward vocabulary can be more powerful and it’s something I aspire to, [but] I don’t always find it easy.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

I feel the same way. As an editor and sometime writer, I find that writing a simple sentence is actually quite hard.

JOANNA WYLD:

The poem I was going to mention at the end of ‘What Can a Song Do to You?’: ‘Does it remind you of a time when you were sad? (So in other words, why? Why is this person crying?) Does it remind you of the time when you were sad? Ah, no. But it reminds me of a time when I could be. It reminds me of a time when I could be…

And I sort of think that’s… mindblowing.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

That particular song has been going around my head for the last few days. Going back to what you were saying with Detectorists making you aware of Unthanks, film and TV does seem to be a major way for people to connect with people now. I sometimes look at the streaming stats for tracks at random, wonder how that’s become the biggest thing, and it’s nearly always some film or TV programme I wasn’t aware of.

JOANNA WYLD:

I guess it’s a route in. I recognise this with classical music as well – I’m lucky enough to have grown up with enough that I’ve absorbed bits and learned about it, done my degrees in it. If I hadn’t done that, that might be my way in as well. And as I don’t have that background with folk song – I like the genre in a broad sense, but I wouldn’t know where to start looking. There’s too much out there, and there are playlists but they can be a bit too rambling.

——

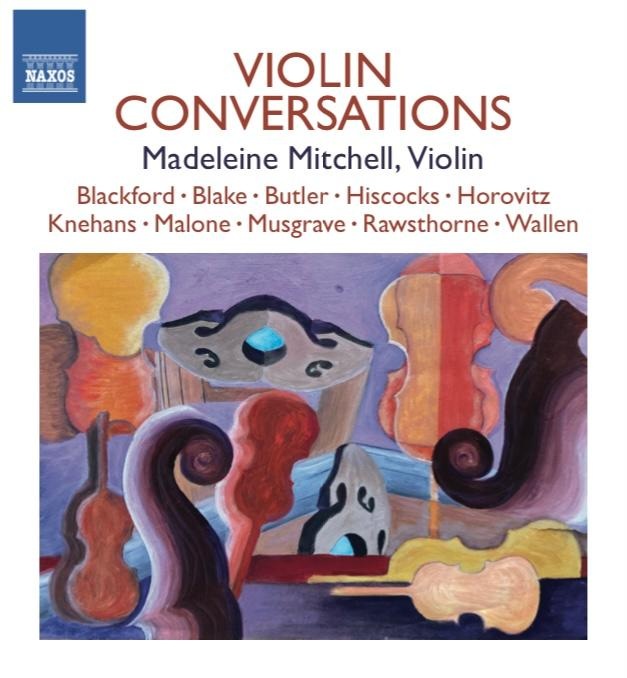

ANYTHING: THE CARDINALL’S MUSICK / ANDREW CARWOOD / DAVID SKINNER: Cornysh, Turges, Prentes: Latin Church Music (1997, Gaudeamus/ASV Records)

Extract: William Cornysh: ‘Salve Regina’

JOANNA WYLD:

This ties a few things together. This is the William Cornysh recording of ‘Salve Regina’, which is my favourite work on that album, but it’s on the Gaudeamus label which I mentioned earlier. I worked with some of the people on that label, but I also know about this repertoire because I was lucky enough at university to study early music with David Skinner, who’s one of the two founders of The Cardinall’s Musick [the other being Andrew Carwood]. They’ve since gone in different directions and David now conducts [a consort] called Alamire. So this is going back a bit, but it was through that university experience that I got to hear this. It’s funny – we were talking about church music earlier but this is English Catholic music of the Tudor era and it’s sad to me that the Catholic Church in this country doesn’t have that kind of choral tradition because we’ve got these riches but for some reason it’s not performed in that church context very often, but nor is it often sung in the concert hall either. Slightly later you get Thomas Tallis and William Byrd, in the Elizbaethan era, that gets mentioned a bit more. But for some reason the Eton Choir Book doesn’t get as much attention and I think it deserves it, so I thought it might be quite fun to bring that in. Because particularly with the Cornysh ‘Salve Regina’, it’s incredible.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

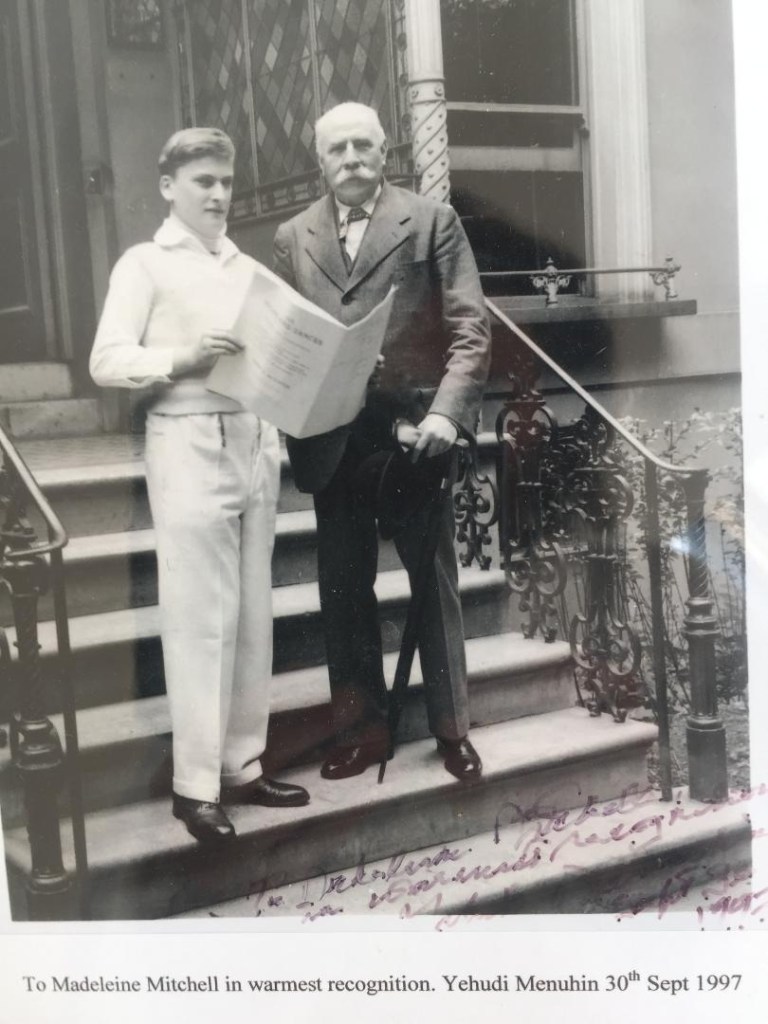

In fact, I’ve got a quote from David Skinner here, from the 1990s: Henry VIII had destroyed most of the musical manuscripts and he says ‘there are literally only two of the choir books I worked from when originally there would have been hundreds.’

JOANNA WYLD:

Yes, Lambeth is the other one, I think?

JUSTIN LEWIS:

He mentions the Eton Choir Book, and the other was Caius?

JOANNA WYLD:

I will have to check my facts because the history of this area is so complex!

JUSTIN LEWIS:

I’m glad you said that! I merely skimmed this, and it felt quite complicated!

JOANNA WYLD:

Really complicated, and I’m sure some of the complexities of how it was written have gone out of the window for me… I learned them a long time ago. I do, very geekily, have a facsimile copy of the Eton Choir Book. I occasionally try and follow along, and it’s quite tricky to follow because instead of it being arranged in score, you’ve got the four parts written separately.

But when I heard the ‘Salve Regina’ at university, it stuck out for me. It’s incredibly beautiful, it takes a bit of time to get into the language and it’s interesting to me that a lot of people who love early music and love contemporary music overlap because early music predates a lot of ‘the rules’ that dominate so much of Western music. With this piece, it’s like you’re walking through a cathedral, meandering, just wandering, but then you get these cadences or these chords, very vivid moments, that feel like light coming through stained glass. And it’s quite a long piece, but right at the end, it just builds and builds up to that high note, which then drops down, and then you have these glorious last two chords. At that point, it’s almost like you’re at the rose window… Even if you’re not religious, music does reflect every facet of who we are, and spirituality is one facet of who we are as human beings. So it’s powerful even if we don’t specifically believe in something. It’s a sense of time travel. It takes you out of yourself and takes you back, but it also kind of elevates as well.

———–

JOANNA WYLD:

At school, I don’t recall learning much pop at all. It wasn’t that I wasn’t exposed to it, but in terms of my actual education, the emphasis was on the history of Western music, classical and symphonic music and so on. My daughter did have to analyse pop – I remember Fleetwood Mac’s ‘The Chain’ being one example. I’ve been a primary school teacher, and I do remember teaching some Stevie Wonder because any excuse, I absolutely love Stevie Wonder, but it was Black History Month and so I brought in his songs about social history, and they all knew ‘Happy Birthday’ but we could talk about how that brought in Martin Luther King Day, which was a lovely way of giving the pupils a sense of the impact music can have.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

Interesting that they knew the song, it’s not one of his you hear that often now.

JOANNA WYLD:

They all knew the chorus, when I sang that bit, they knew that, but they didn’t know the verses or the lyrics so they just thought of it as generic. It’s not my favourite Stevie song – I’ve got so many – but it’s an example of how powerful music can be.

———

You can find out more about Joanna, and her work, at her website, Notes Upon Notes: https://www.notes-upon-notes.com

You can follow her on Bluesky at @joannawyld.bsky.social.

Also, find out more about Dawn of the Squid at their website: https://dawnofthesquid.co.uk

—–

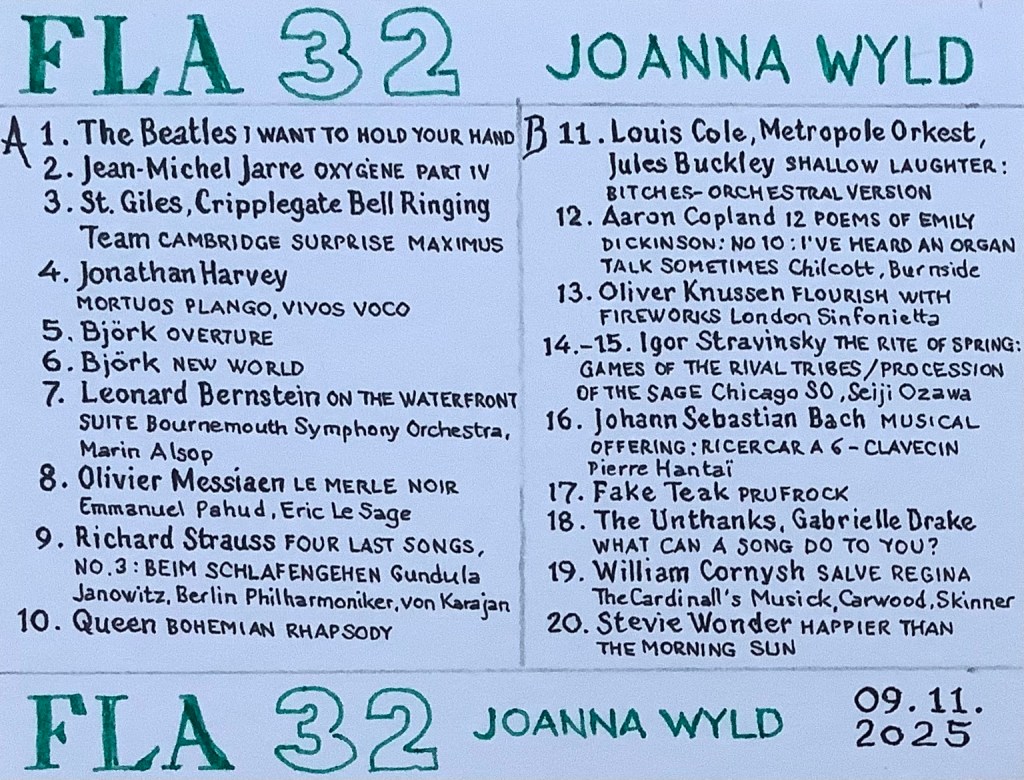

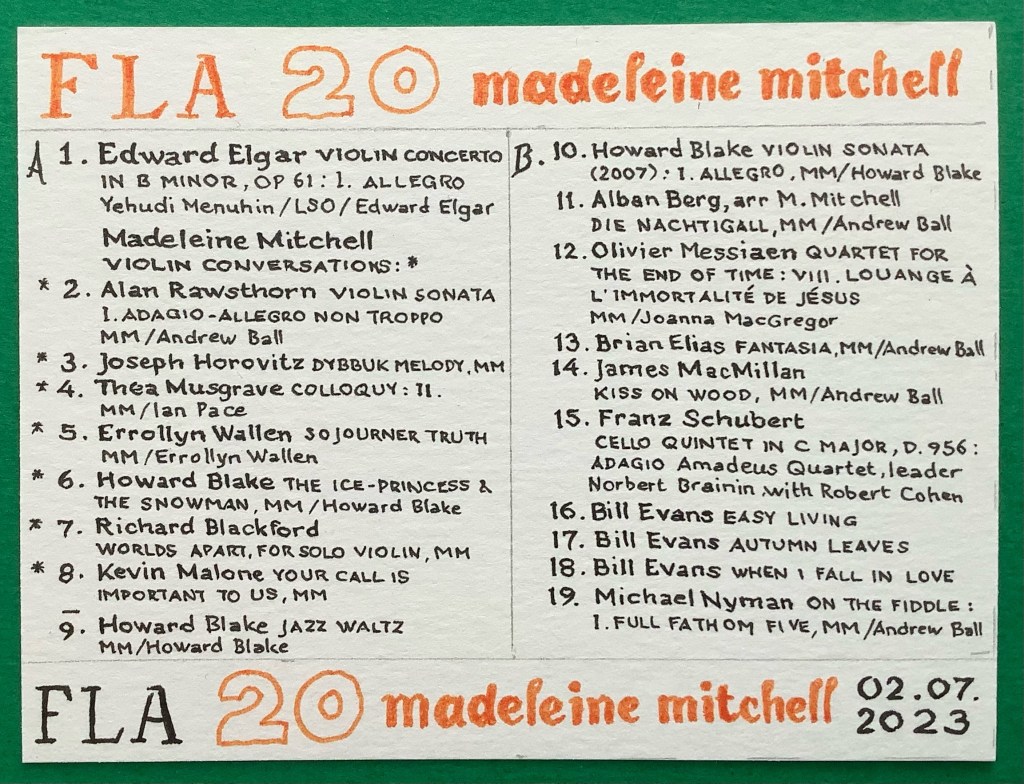

FLA PLAYLIST 32

Joanna Wyld

For the time being, this site and project uses Spotify for the conversation playlists, but obviously I disapprove that Spotify doesn’t pay artists and composers properly, and other streaming platforms are available, as are sites to buy downloads and buy recordings. For consistency, you can also listen to the selections via YouTube (where available), and links are provided in each case, below.)

Thanks to Tune My Music, you can also transfer this playlist to the platform or site of your choice by using this link: https://www.tunemymusic.com/share/QWjXV28T8E

Track 1:

THE BEATLES: ‘I Want to Hold Your Hand’:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XT4pwRi2JmY&list=RDXT4pwRi2JmY&start_radio=1

Track 2:

JEAN-MICHEL JARRE: ‘Oxygène, Part IV’:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_PycXs9LpEM&list=RD_PycXs9LpEM&start_radio=1

Track 3:

ST GILES, CRIPPLEGATE BELL RINGING TEAM: ‘Cambridge Surprise Maximus’: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=o8rwhJHt9Ds&list=RDo8rwhJHt9Ds&start_radio=1

Track 4:

JONATHAN HARVEY: ‘Mortuos Plango, Vivos Voco’:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0T-H-fVlHE0&list=RD0T-H-fVlHE0&start_radio=1

Track 5:

BJÖRK: ‘Overture’:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6k4xT0qjUW4&list=RD6k4xT0qjUW4&start_radio=1

Track 6:

BJÖRK: ‘New World’:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=eNma-h_urvs&list=RDeNma-h_urvs&start_radio=1

Track 7:

LEONARD BERNSTEIN: ‘On the Waterfront Suite’

Bournemouth Symphony Orchestra, Marin Alsop:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=t4isx_tGYwM&list=RDt4isx_tGYwM&start_radio=1

Track 8:

OLIVIER MESSIAEN: ‘Le merle noir’:

Emmanuel Pahud, Eric Le Sage:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hT8MQpg7oTo&list=RDhT8MQpg7oTo&start_radio=1

Track 9:

RICHARD STRAUSS: ‘4 Letzte Lieder [Four Last Songs], TrV 296: No. 3: Beim Schlafengehen’:

Gundula Janowitz, Berliner Philharmoniker, Herbert von Karajan:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=t5n0DqFlpMY&list=RDt5n0DqFlpMY&start_radio=1

Track 10:

QUEEN: ‘Bohemian Rhapsody’:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xG16sdjLtc0&list=RDxG16sdjLtc0&start_radio=1

Track 11:

LOUIS COLE, METROPOLE ORKEST, JULES BUCKLEY: ‘Shallow Laughter: Bitches – orchestral version’: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bEmMAG4C1BE&list=RDbEmMAG4C1BE&start_radio=1

Track 12:

AARON COPLAND: ’12 Poems of Emily Dickinson: No. 10: I’ve Heard An Organ Talk Sometimes’:

Susan Chilcott, Iain Burnside:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SvKLlCf2TWE&list=RDSvKLlCf2TWE&start_radio=1

Track 13:

OLIVER KNUSSEN: ‘Flourish with Fireworks, op. 22: Tempo giusto e vigoroso – Molto vivace’:

London Sinfonietta:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wLkTfXPC-TU&list=RDwLkTfXPC-TU&start_radio=1

Track 14:

IGOR STRAVINSKY: ‘The Rite of Spring, Part 1: V. Games of the Rival Tribes’:

Seiji Ozawa, Chicago Symphony Orchestra:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XiAr76Qs8WY&list=RDXiAr76Qs8WY&start_radio=1

Track 15:

IGOR STRAVINSKY: ‘The Rite of Spring, Part 1: VI. Procession of the Sage’:

Seiji Ozawa, Chicago Symphony Orchestra:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nvBog5Tej2I&list=PL-XNw6p4EDBv7-H-z2Vo_c3sB3rvIxt7-&index=6

Track 16:

JOHANN SEBASTIAN BACH: ‘Musical Offering, BWV 1079: Ricercar a 6 – Clavecin’:

Pierre Hantaï:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5K07rF5xOvQ

Track 17:

FAKE TEAK: ‘Prufrock’:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=L5-1prkhHjU&list=RDL5-1prkhHjU&start_radio=1

Track 18:

THE UNTHANKS: ‘What Can A Song Do to You?’

[Poem read by Gabrielle Drake]:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Jzqb_78LUkI&list=RDJzqb_78LUkI&start_radio=1

Track 19:

WILLIAM CORNYSH: ‘Salve Regina’:

The Cardinall’s Musick, Andrew Carwood, David Skinner:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pQprxgtbk4E&list=RDpQprxgtbk4E&start_radio=1

Track 20:

STEVIE WONDER: ‘Happier Than the Morning Sun’:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=S4PcSOLtf-U&list=RDS4PcSOLtf-U&start_radio=1

Maybe because it’s felt like the 24-hour news media has been laughing at us for months, but I’ve started to be plagued by the memory of a most disturbing record.

Maybe because it’s felt like the 24-hour news media has been laughing at us for months, but I’ve started to be plagued by the memory of a most disturbing record.