I first became aware of Joanne Limburg’s work in 2010 when she published the extraordinary memoir, The Woman Who Thought Too Much, about her life experiences with obsessive compulsive disorder. Hilary Mantel, no less, recommended it in The Observer newspaper. Immediately after finishing it, I found Joanne on Twitter to thank her for writing it, and we’ve been following each other there ever since.

Joanne has since been diagnosed as autistic, and has completed two further works of non-fiction : Small Pieces (2017), about the loss of her brother and mother; and most recently, Letters to My Weird Sisters (2021), a sequence of letters to four women in history who didn’t ‘fit in’ with their respective societies.

Her career as a poet flourished after she won the Eric Gregory Award in 1998, since when she has published three volumes of poetry for adults – Femenismo (2000), Paraphernalia (2007) and The Autistic Alice (2017) – and one volume for younger readers, Bookside Down (2013).

Joanne’s work is thoughtful, imaginative, moving and often humorous, and when I was first considering potential guests for this series, Joanne was in my mind from day one. So I am delighted to say that one morning in July 2023, we had a most diverting conversation about music and writing. Quite often, I only realise a conversational theme during the edit, and in this one, we both keep coming back to it: the concept of permission in creativity.

—-

JUSTIN LEWIS

You’re the first person who’s been on this who’s my school year age. I think there’s only a few weeks between us.

JOANNE LIMBURG

I think you’re just a few weeks younger, yes.

JUSTIN LEWIS

So this could be interesting in terms of how we experienced the same things in our different parts of the country. What music was being played in your house when you were small, then? What records did your parents have in their collection?

JOANNE LIMBURG

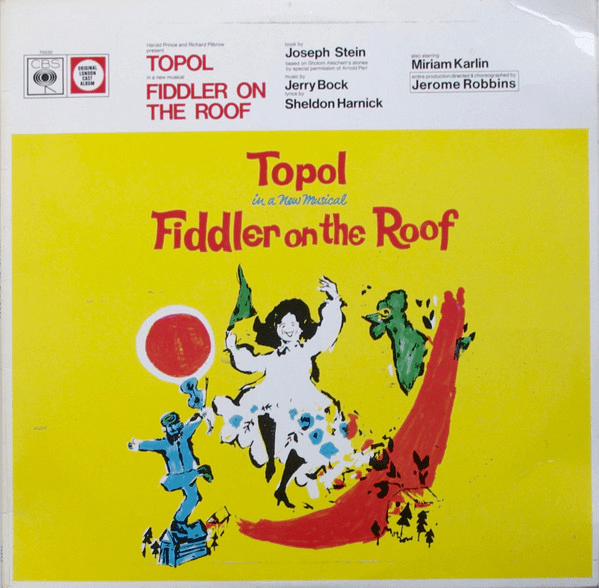

I remember being interested in my parents’ albums according to how colourful they were. I loved the Fiddler on the Roof album, which had a really colourful sleeve.

JOANNE LIMBURG

That had a really colourful sleeve, and Wally Whyton’s Party Playtime, which was for kids. My mum liked opera and my dad liked Sibelius, but I don’t remember them being played much when I was young, they were just sitting there in the rack. I remember Junior Choice being on Radio 1. I remember watching Top of the Pops. And I realised the other day that one of my earliest memories is probably seeing 10cc perform ‘Donna’ (1972). Because I have a particular memory of how Lol Crème looked at that point, because he looked in some ways like my dad. My earliest pop memory – I found it the other day on YouTube – was an advert for Jelly Tots.

JUSTIN LEWIS

‘Rowntrees Tots, please yourself.’

The soundtrack to the 45-second Rowntrees Tots advert (1974), written and performed by The First Class under the name ‘The Tots’.

JOANNE LIMBURG

There was a sort of tie-in single. ‘Don’t just sit there upon the shelf.’

JUSTIN LEWIS

I remember the ad, but I had no idea there was a single. ‘Please Yourself’ by The Tots (1974) – from the same team who made ‘Beach Baby’ by The First Class. The days of pop writers writing adverts and then adapting them for actual singles with the brand names taken out. Like David Dundas with ‘Jeans On’.

JOANNE LIMBURG

Something else I remember: When I was three, my parents recorded me singing ‘Long Haired Lover from Liverpool’ and also when I was three, I have a memory of being in my uncle’s estate car. I was the youngest family member on an extended family trip to Knebworth. I can remember the other kids laughing because I started singing Suzi Quatro’s ‘Can the Can’ very earnestly. I’m sure I didn’t sing it in any kind of tuneful way, and I’m sure I got the words wrong as well. But this is how 70s it was: while the younger kids, me and two of my cousins, were on the back seat, the older kids were in the boot. [Laughter]

——

FIRST: ELVIS PRESLEY: ‘Way Down’ (RCA, single, 1977)

JOANNE LIMBURG

Memories can detach and reattach themselves, but I remember buying this specifically from WHSmiths in Temple Fortune [in northwest London] – although maybe it was in Golders Green. It was quite small, and you had to go up to a desk and ask for it.

I had been given a little record player for my seventh birthday, and a friend and a neighbour gave me a load of records to go with it – not necessarily things I would have chosen… Things like… Guys and Dolls?

JUSTIN LEWIS

Oh yeah, the group. Who spawned Dollar.

JOANNE LIMBURG

Exactly. And one called ‘Who’s in the Strawberry Patch with Sally?’

JUSTIN LEWIS

Which I think was by Tony Orlando and Dawn.

JOANNE LIMBURG

I also remember ‘Knowing Me, Knowing You’ by ABBA turning up. Which I think was after ‘Way Down’?

JUSTIN LEWIS

Before, in fact!

JOANNE LIMBURG

But ‘Way Down’ is the one I remember buying.

JUSTIN LEWIS

The strangest thing is, I do not remember the announcement of the death of Elvis at all. Do you?

JOANNE LIMBURG

I do. I remember we were on holiday in Scotland, it happened over the summer in August [1977]. In fact, on a different holiday in Scotland, a year later, Pope Paul VI died, and we were not Catholics, obviously, we were Jews, but I remember it because we were in a different place. With Elvis, either it was on the car radio, or my parents were talking about it while they were driving us through the Highlands. I don’t know that I was aware of him until he died and it was explained to me who he was. Though I probably heard ‘Blue Suede Shoes’ or ‘Hound Dog’ playing somewhere, so was aware of his voice in the background.

JUSTIN LEWIS

‘Way Down’ had just been released in the UK, and there was no sign that it was going to be a particularly big hit. It went in the charts at 46, the next week – the week Elvis died – it went up to 42, so not showing any real signs of going anywhere. And then… it goes to number 4, and then number one for five weeks.

JOANNE LIMBURG

He did the ultimate publicity stunt… by dying.

JUSTIN LEWIS

The last thing he ever recorded.

JOANNE LIMBURG

Obviously, I liked it then, but I don’t think of it as a particularly momentous piece of music.

JUSTIN LEWIS

But something else I found out. Those really low notes, at the end of each chorus.

JOANNE LIMBURG

That’s probably why I bought it. Because there’s a kind of novelty thing that amuses a seven-year-old, those low notes.

JUSTIN LEWIS

I still can’t get anywhere near them even now. But I assumed it was Elvis singing them. And it isn’t. It’s the backing singer. He had this backing singer called J.D. Sumner (1924–98), who had this background in gospel and country music. Basically, his big thing was he could do these incredibly low notes. At the end of ‘Way Down’, that last note is C1, which is three octaves below middle C. I think it’s the lowest note sung on a major hit record.

JOANNE LIMBURG

It’s almost infrasound, isn’t it?

—–

JUSTIN LEWIS

You first came to my attention with The Woman Who Thought Too Much. I think I either read the Hilary Mantel review of it, or I saw it in a shop. And at the time, for various reasons, I wanted to find out more about obsessive compulsive disorder, and this was such a well-written, sensitive, accessible and relatable account. In fact, so many of your books have been so enlightening and helpful to me.

JOANNE LIMBURG

Well, there are these sorts of parallels in our life paths. Because I write autobiographically.

JUSTIN LEWIS

Yes. And in some ways, we have different backgrounds, but… we’re the same age, we’ve lost a sibling at roughly the same age, we lost our fathers at roughly the same age. And I’m currently in the process of getting assessed for autism.

JOANNE LIMBURG

It’s interesting because I sort of think of you as my first actual Twitter friend.

JUSTIN LEWIS

That’s a really lovely thing to say.

JOANNE LIMBURG

I think we’ve known each other on Twitter for 13 years. Sometimes, I’ll be watching Top of the Pops on BBC4 and I’ll say to my husband, ‘Justin just said this’, and early on, I tried to explain you, and I said, ‘He’s a male me, really.’

JUSTIN LEWIS

How wonderful. I’d always felt I was in that grey area where I didn’t know, and when I started to read your stuff, it made so much sense to me.

One reason I’m doing this series at all is because I feel a slight sense of unfinished business with music. I found it quite awkward being a musical performer, I started a music degree, didn’t finish it, didn’t know what to do, really.

JOANNE LIMBURG

Oh, I didn’t know you were actually a musician yourself, because you don’t mention that, funnily enough.

JUSTIN LEWIS

I don’t talk about it very much. I got Grade 8 flute when I was fifteen. I was okay, and I got into university partly, I think, because I had perfect pitch.

JOANNE LIMBURG

It often goes with autism.

JUSTIN LEWIS

Right, right. But obviously, neither of us knew at the time what this was, none of it was explained. Because we were in this funny situation and…

JOANNE LIMBURG

We both were and were not autistic children.

JUSTIN LEWIS

So were you learning instruments at school, having lessons?

JOANNE LIMBURG

Because I knew that my grandfather had played the violin, I imagined he was a professional. Actually, he was an amateur player, he died when my mum was very small so I never met him. I persuaded my parents to let me start the violin, so I played the violin from eight to fourteen. In fact, for my ninth birthday, I got the record of David Oistrakh playing Beethoven’s Violin Concerto – I still play that now. But I wasn’t that great – I got to Grade 4 and the piano up to about Grade 3, but I didn’t have the discipline to do it properly.

Also, I think I found schoolwork very easy, and didn’t understand that just because you couldn’t do something straight away, it didn’t mean you were rubbish at it. I was immature – I mean, why wouldn’t I have been, I was a child! – but I didn’t get practising at that age. I think I was fairly musical – not perfect pitch, although I’ve got reasonable pitch. But it never went anywhere, and then when I was eleven, I went to this very academic girls’ school where people were there on music bursaries, and I felt just crap by comparison. There were lots of teachers attached to the school, so I was given one of them, and she was just horrible to me. She said to me, ‘You have to join the orchestra.’ So I joined the second violins and it was one of the most demoralising moments of my entire life. I just couldn’t do it.

JUSTIN LEWIS

Was it about the music, or the dynamic or the space you were playing in?

JOANNE LIMBURG

I couldn’t quite read [the score] at that speed. The other frustrating thing is: I find it difficult to sing with other people, so I don’t know how people sing in harmony. Because if I’m near someone else who’s singing a different tune, I can’t stop hearing it, and I get lost and tangled up. We were singing some Schumann in the choir once and I remember getting completely lost at one point, and there were all these girls obviously singing around me very confidently. So – you know, I’m not particularly musically talented, but I’m not tone deaf, I would say.

JUSTIN LEWIS

I really used to think that we all heard music the same way, that we could all hear the same things.

JOANNE LIMBURG

And we don’t at all.

JUSTIN LEWIS

I’m really aware of it now, my reaction to certain stations on digital radio, and I know it isn’t the actual music some of the time.

JOANNE LIMBURG

There’s a really high-pitched noise.

JUSTIN LEWIS

I have heard you talk about an aversion to loud noise, and that’s happening more and more with me now. Although it depends what the noise is, where I am, how I’m feeling. Has that been the case for you as well?

JOANNE LIMBURG

Always been the case. I’ve always been very upset if something goes bang. I’ve always been scared of balloons.

JUSTIN LEWIS

And does that extend to music as well as sound?

JOANNE LIMBURG

I don’t like it if it’s turned up beyond a certain point, I find it painful. So I don’t really like going to concerts cause it’s turned up so loud at them. It hurts my ears. I’ve often had to leave events earlier because the music was so loud.

JUSTIN LEWIS

I do remember as a kid about noise levels because my dad used to be a drummer in various groups and things, and we’d accompany him to things. I went with him to a drum clinic when I was about 13, which he wasn’t playing in, but there were a lot of absolute virtuosos in that. I’d probably get more out of it now, but it was about four hours of drums. A very late night, that one.

JOANNE LIMBURG

I always think, it’d be great to learn drums, great to learn bass. It’s always the rhythm section I want to be in, but realistically, when you’re young and you think about being in a band, and you just look at them on the stage, or in an orchestra – I don’t know how they manage to stay together. They can all start together and stop together. That must take a long time to get there, and you’re doing the same movement again and again and again. And with something like bass and drums, you’re often playing the same four notes again and again, and I suppose you must have to go into some kind of trance-like state. There must be some element of muscle memory because if you stop, you’d suddenly go: ‘What am I doing?’ It’s like if you walk down the stairs and you start noticing your feet.

JUSTIN LEWIS

Or thinking about the process of breathing. Whereupon it suddenly gets more difficult.

JOANNE LIMBURG

Kevin Godley, 10cc’s drummer, was asked, ‘How can you do all those different things at the same time? He said, ‘It’s not different things at the same time. It’s different parts of one thing.’

—

JUSTIN LEWIS

We nearly met, didn’t we? We nearly met at the British Library about 10 years ago.

JOANNE LIMBURG

When I might have been looking at Queen Anne’s letters, when I was researching my novel about her, A Want of Kindness.

JUSTIN LEWIS

Which is the one book of yours I haven’t actually read yet.

JOANNE LIMBURG

It’s quite different from the others – partly because it’s the only fiction. And because I decided, insanely, that I was only going to use words that were around at the time. I don’t know if it feels like an accomplishment to have done that. I wouldn’t want to do it again. It was a great big thought experiment to put myself in someone else’s mind so I needed the furniture of their mind, not mine. I read the King James Bible, and the Book of Common Prayer, and John Foxe’s Book of Martyrs, the sorts of things she would have had in her head, and her letters, and I got a sense of her voice from that.

I don’t think it did too badly – it came out in America – but it was marketed as a historical fiction book and it’s more like fiction that happens to be historical. Also, difficult things were going on in my family at the time, and it was an escape, in retrospect: ‘Yes, yes, I’m just going to go to the 17th century and work this all out there.’

JUSTIN LEWIS

I heard you on a podcast a while back saying you were working on another novel, is that still happening?

JOANNE LIMBURG

I thought about it. But that’s gone on the extreme back backburner because I don’t really feel like I’m a novelist, as if people might expect another novel from me. Like I didn’t do all of Queen Anne’s life, so there’s a possible sequence in the air, but I found having a novel out very difficult, and I found working on it very difficult.

I found another interesting story. A woman called Sarah Scott (1720–95) wrote a best-selling book called Millenium Hall (1762), about this ideal place with all these women who have various racy back stories – which is probably what made people read the book. These independently wealthy women pool their resources and live in Millenium Hall where they spend their time studying and sketching and making music and living the 18th century idea of a good life, and also doing good works on the side.

So there’s a school and there’s some cottages. And there’s also – interesting in disability theory – a walled-off bit where they have various disabled people who are thought of as looking different or disfigured, living together in a community, and they support them.

Sarah Scott had smallpox very badly as a young woman and was left very marked by it. So this would have been a concern of hers, and she tried to do this [experiment] in real life. It obviously fell through because of all those real-world things: personalities, money, health. And I thought there’s a plot there, in the gap between ideal and reality.

Scott’s book is narrated by a man who visits, and it records his wonder and amazement as he’s shown around this extraordinary place by these marvellous virtuous women. So there are these ‘gorblimey guvnor’ monologues by people they helped, saying how much they’ve been helped, how the ladies have shown them how to be better, more virtuous Christians and all this. It would have been thought of as progressive then, but it still speaks to how we try and help people now, and how you see people getting outraged if the objects of their charity don’t show gratitude. And I also wondered what these people said when their backs were turned. There’s a lot of material in it but I don’t know if I can spend another five years writing a novel on spec.

JUSTIN LEWIS

I tried to write a novel which I suspect was thinly veiled memoir, and it didn’t really feel believable as fiction. Maybe I should try again. But I remember you mentioning that you originally considered writing The Woman Who Thought Too Much as a novel, and then you concluded that you had to make it about you, you had to say, ‘Look, this is me, this is what happened.’

JOANNE LIMBURG

Yeah, it becomes about testimony and witness, and the truth-claim you make about it: ‘No, I’m sharing experience. This is me, the value of that.’ And also it’s not that I ‘don’t follow fiction’, it’s not that I ‘don’t enjoy it’, it’s not that I ‘can’t understand it’ – all those various stereotypical things about autistic people. But it seems like a lot of work to me to make people up. I don’t think it’s a lack of imagination so much as ‘I can’t be bothered.’

JUSTIN LEWIS

Obviously a lot has happened in your life, to you, and to those around you.

JOANNE LIMBURG

Yes, my brother took his own life while I was writing The Woman Who Thought Too Much.

JUSTIN LEWIS

I hope this is okay to ask you about this – as that tragedy is the last thing that happens in that book – but had you already completed a draft?

JOANNE LIMBURG

No, no, it’s okay. It happened while I was drafting. There’s one bit in the book where I talk about feeling really, really unbearable and I don’t say why. And I think that was when I returned to the book after taking weeks out. Because I had to go back to it. The publishers said, ‘You can take a break’, but I thought it better to just push on.

JUSTIN LEWIS

Because you’ve committed by then to a certain level of ‘This is what happened’?

JOANNE LIMBURG

Yeah, and I had enormous guilt, which I do talk about in the book. Because about 18 months before my brother died, he’d been diagnosed in America – where he was living – with what was then called adult ADD. And I just went, ‘Oh this changes things, can I mention it in the book?’ – and he totally panicked, because he didn’t want anyone at work to know. And I was just really ashamed. And I still am actually guilty about that. Although I think probably most people who are writing a book about mental health would have responded like that at that point. In retrospect, it looks especially callous, but I think I’m being a bit hard on myself really.

JUSTIN LEWIS

It’s a dilemma I know I have as well: How do you write about other people? You can write about your own response, but you also have to think, How would I feel if somebody was writing about me? I always have that thought when I’m trying to write about anybody. But you can only take that so far, sometimes.

JOANNE LIMBURG

In The Woman Who Thought Too Much I made a conscious decision that I was the protagonist and OCD was the antagonist. And so I kept writing about other people to a minimum, which had the unfortunate effect of making me look very self-obsessed. But I just wanted to protect everyone. I know someone who’s a crime writer, and she read that book and said, ‘Oh, there’s a suppressed narrative about your mother. Is that deliberate or unconscious?’ And I said, ‘Oh it’s pretty deliberate. And then that suppressed narrative came to the fore in the book I wrote after Mum died [Small Pieces, which is also about my brother]…

—–

LAST: GABRIELS: Angels & Queens (Part I: 2022; Part II, 2023, Atlas Artists/Parlophone)

Extract: ‘Love and Hate in a Different Time’

JUSTIN LEWIS

Slightly confusingly, this album has appeared in two volumes and there’s now a deluxe version available of both.

JOANNE LIMBURG

I saw them on Later with Jools Holland. I thought, ‘They’re amazing’, but also, ‘I’ve heard that voice before, it’s something that’s been played a lot in the background of things.’ And then I found out it was ‘Love and Hate in a Different Time’.

JUSTIN LEWIS

I’m so glad you chose this, it’s one of my favourite singles of the last few years – and I’ve just discovered it’s one of Elton John’s favourites as well. Because did you see his Glastonbury set?

JOANNE LIMBURG

Oh yes! He had the guy on with him, Jacob Lusk.

JUSTIN LEWIS

For ‘Are You Ready for Love?’.

JOANNE LIMBURG

I just love voices like that, and when someone’s doing something different with sound.

JUSTIN LEWIS

I hadn’t consciously checked who produced this album until I was doing some preparation for this, and it’s Sounwave who’s worked on all the Kendrick Lamar albums. So the production is this really unusual mix – this very special honeyed voice on top, and these horns and strings that feel like they’ve wandered in from Al Green and Detroit Emeralds records in the 70s, but then you’ve got these murkier, distorted textures in the middle which bring to mind Thundercat’s records too. A very powerful combination.

JOANNE LIMBURG

It seems to speak somehow to the times we’re in. And he’s got one of those gospel-trained voices, my favourite sort of voice. It’s a cliché, but I imagine it’s called soul music, because you can hear someone’s soul. It’s not just that gospel singers use the biblical language, it’s the tone… I don’t know much about singing voices, I couldn’t tell you what the technical terms are, but there’s something that makes you pay attention and say, ‘Ohh yes, this is human.’

—-

JUSTIN LEWIS

Your most recently published book, and just one reason I’ve wanted to get you on this ever since I first had the idea, is Letters to My Weird Sisters: On Autism, Feminism and Motherhood (2021), a fabulous book.

JOANNE LIMBURG

Thank you very much.

JUSTIN LEWIS

Which as the title suggests is a sequence of four letters you’ve addressed to women in history: Virginia Woolf (1882–1941), Adelheid Bloch (1908–40), Frau V (19th/20th century; exact dates and real name unknown) and Katharina Kepler (1546–1622). And I was interested to hear you mention two inspirations for it. One was Steve Silberman’s NeuroTribes book (2015), which I’ve since read and loved… but also, Beyoncé’s Lemonade (2016).

JOANNE LIMBURG

Yes! There were a few other inspirations, but she was one of them. I saw the film of Lemonade, and I thought, She is not exhibiting herself. It’s like: ‘I’m talking to my fellow Black women, and there’ll be stuff the rest of you don’t understand and I’m not going to explain it to you. But you’re allowed to listen. But I’m not talking to you. This is how we talk when it’s us, and it’s our reality.’

I was really impressed by that. Well, I don’t understand ‘Formation’, I don’t know what ‘I got hot sauce in my bag, swag’ means. But a point is being made: ‘You, the white listener, are not at the centre of things. We’re talking now. You sit. You listen.’ And so I wanted to make an analogous move , decentering non-autistic people.

JUSTIN LEWIS

What kinds of responses have you had from neurotypical people since its publication?

JOANNE LIMBURG

Pretty good and actually, I had a review from quite a well-known clinician who just took it on the chin, really.

JUSTIN LEWIS

This reminds me of when you’re a kid, and you’re listening to something or reading or watching it, and there are references you don’t necessarily understand, but you think, ‘You know what? It’s fine. One day I will understand this.’ Not everything has to be explained.

JOANNE LIMBURG

No. Because of the way I write, I probably made things clear anyway. But what I deliberately didn’t do in that book is something people quite often do when writing about their condition (and which I did do in The Woman Who Thought Too Much). They will say something like, ‘According to the DSM, which is the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, the National Autistic Society says…’ and I just thought, Fuck that.

JUSTIN LEWIS

So you reclaimed the word ‘weird’?

JOANNE LIMBURG

Yeah, exactly. I thought, This is about my experience, this is about flipping the mirror around and saying no, this is how the world looks to us. I was talking about this to someone the other day, and I said, ‘The thing about autism is, it’s always been a spectacle.’ There’s a woman, I think, called Grunya Sukhareva (1891–1981), who first identified that group of children in Russia, and whose work was possibly ripped off by Leo Kanner and Hans Asperger… but that’s another thing. It starts with Kanner looking at a group of children, Asperger looking at a group of children and describing them. So right from its inception, its [first] appearance in the wider culture, it’s an outside-in phenomenon, which has led to so much suffering and so much oppression. So I thought: No. This is absolutely inside-out.

I’m going to go off on a long tangent now – sorry!

JUSTIN LEWIS

Don’t worry. Please go ahead!

JOANNE LIMBURG

When I was studying psychoanalysis years ago, I was reading a paper by Anna Freud, who talked about how she’d been dealing with child survivors of the Holocaust. And she noticed that they identified not with the adults they were with, but with adults like the guards, the non-Jewish staff, and that this was a protective measure. You can see how it’s a protective measure, because ‘I’m not in this powerless suffering group. I’m one of the winners. I’m one of the people in charge.’

In Weird Sisters, I talk about ‘the socially gracious Joanne’, and I think about her in relation to someone else’s concept of the ‘nice lady therapist’…and we do this all the time; we want to identify with the ones who are in power – not the people who are having stuff done to them, but the people with the power, the people in control. And one way you can do that is by taking on medical language. ‘I’m on your side.’ And it winds up propping up something that’s often called epistemic injustice, where to find out knowledge about yourself, you have to go to someone who’s extracted it and borrow it back in their terms. And I thought, Absolutely not. I’m done with that. I can understand the protectiveness of that identification, but I think my rejection of it is a reflection of how confident and safe I feel now.

Relative to how I felt before that, I can say no. I don’t need to borrow your authority. And I don’t need your approval either.

JUSTIN LEWIS

And you chose the word ‘weird’ for this book because you didn’t want to posthumously diagnose the people that you’re writing about, the people you’re writing to.

JOANNE LIMBURG

And Steve Silberman’s very clear as well that you can’t do that. It’s not ethically right, and it’s bad scholarship.

JUSTIN LEWIS

Did you have a longer list of people that you were going to include in the book?

JOANNE LIMBURG

Oh yes, yes.

JUSTIN LEWIS

And were there any people from the world of music you were considering for inclusion?

JOANNE LIMBURG

I think I thought about Hildegard of Bingen (c. 1098–1179). I can think of lots of men in music… Glenn Gould (1932–82), for instance. Autism and music go together quite well, and I think sound engineering or record production is quite a good job for a lot of autistic people because of the detail.

JUSTIN LEWIS

Though it’s quite surprising there are still relatively few record producers who are women, unless they’re producing themselves.

JOANNE LIMBURG

Yeah. I’m sure that’s entirely for social reasons. I love a particular kind of BBC Four-type music documentary when they tell you how the tracks are put together. I love tracks like ‘Memphis Soul Stew’ by King Curtis which narrates its own construction. Sometimes I will listen to a particular track, but to just one bit of it, like just the bass – on, say, ‘Video Killed the Radio Star’, or just the drums, like on ‘Reverend Black Grape’. It has nothing to do what time in your life you’ve associated it with, or the image of the band. It’s entirely to do with: What is this thing made of? And when I see people talking about production or sound engineering, with that kind of enthusiasm, I 100% understand.

JUSTIN LEWIS

I find that not enough is talked about arrangement in music. It’s such an important aspect. And when people say ‘Music sounds the same’, what they often mean – I think – is that too many arrangements sound the same. [Joanne agrees] I mean part of the problem now is that so many people are using the same software to make records, whereas pre-digital, people were having to find their own way.

JOANNE LIMBURG

I love hearing stories about tape loops – ‘we cut up these tape loops’ and all that ingenuity.

JUSTIN LEWIS

I’m not here to plug my upcoming book, but quite a few studio stories in that one.

JOANNE LIMBURG

They’re the stories I like. I don’t care whether they got pissed and threw a TV out the window or not. I want to know how they made the record.

JUSTIN LEWIS

The stories of people getting drunk or having sex are a bit dull. I don’t really believe in excess for its own sake. And it’s been written about so much, and it’s led to some terrible things happening in the entertainment world.

But also, it’s considered perfectly normal, apparently, for musicians to stand on stage for two hours a night, on a 300-date tour of the world, in different cities, jet-lagged and missing their loved ones. And we somehow expect them to not take drugs or be screwed up in some way. A strange thing to demand of people.

JOANNE LIMBURG

I know. I remember talking to a musician years ago. I think Amy Winehouse had just died, sadly, and we talked about her, and about Michael Jackson. I said, ‘It’s such a dangerous situation to be worth that much money to so many people. It’s not going to do you any good.’

JUSTIN LEWIS

But something that recently happened which came too late for inclusion in my book, unfortunately, was Lewis Capaldi at Glastonbury. A very interesting moment. The crowd understood it, they ‘got it’, which was encouraging.

JOANNE LIMBURG

People our age and older complain about millennials and Gen Z being all oversensitive, but I think it’s a great quality they have. They recognise that it’s not easy to be human, and we could just be compassionate with each other rather than saying ‘buck up’.

JUSTIN LEWIS

It’s not easy to be a performer sometimes.

JOANNE LIMBURG

God, no.

—-

ANYTHING: GEORGE MICHAEL: ‘A Different Corner’ (Epic Records, single, 1986)

JUSTIN LEWIS

I haven’t seen the Wham! documentary yet, because I don’t have Netflix anymore.

JOANNE LIMBURG

Oh that’s a shame. I watched the documentary with my husband.

JUSTIN LEWIS

I just wasn’t using it. But it sounds like the concept of Wham! came out of friendship. George Michael and Andrew Ridgeley were friends, they never ever fell out as far as I know, and there was a lot of generosity from both sides about how they existed. There was never any kind of acrimony, during or after. And I’ve read about how Andrew almost gave George permission to be a pop star, which he might not have done otherwise. He’d have probably become a songwriter, but as a way of getting his songs noticed…

JOANNE LIMBURG

Yes, this extraordinary generosity, like Andrew was George’s booster rocket. And he was OK with that. I mean, yes, a well-paid booster rocket, but still, it’s an extraordinary lack of ego.

JUSTIN LEWIS

There were a lot of jokes at Andrew’s expense in those days especially, but so much of pop music is about image.

JOANNE LIMBURG

And a persona on to which people, especially very young people, can project stuff.

JUSTIN LEWIS

With many of the Wham! records, I have little doubt that even if Andrew didn’t write the songs, he was certainly listening to a lot of music. They once reviewed the new singles in Smash Hits, and he had as many astute things to say about the records as George did.

JOANNE LIMBURG

At the time, I had not entirely positive feelings about Wham!, I think. Probably to do with the age we were, let’s be honest. I associated them with the ‘popular girl’/’mean girl’ people. Especially as Wham! came from my part of London as well. So it was all very close.

JUSTIN LEWIS

You were in… Stanmore, is that right?

JOANNE LIMBURG

Yeah, so George’s father’s restaurant was in Edgware, and my family went there at least once. I think I probably knew people who knew them because some people at my school were from Bushey. But also, I didn’t like the plasticky-ness of Wham!, I found it actively off-putting at the time. I knew it was catchy, and that was undeniable.

JUSTIN LEWIS

I genuinely liked the first album, Fantastic!. And after that ‘Wake Me Up Before You Go-Go’ was a complete break with the past, and it got such a slagging in the press.

JOANNE LIMBURG

I liked that one. I really liked it, my mum liked it.

JUSTIN LEWIS

Yeah, yeah. But it was a very dramatic left-turn from what they’d been doing previously. I wasn’t buying the records by then, although I had the first Hits Album compilation (1984) and played ‘Freedom’ quite a lot on that.

JOANNE LIMBURG

Which I never liked at the time, for some bizarre reason, or ‘Last Christmas’ – but not for any particular reason.

JUSTIN LEWIS

So what changed your mind with ‘A Different Corner’, the solo George single from spring 1986, while Wham! were still a thing?

JOANNE LIMBURG

I can see how it tracks a change in my attitude to George Michael, and to pop. Because, you know, put me back at that age: I’m the sort of nerdy, bookish outsider, so naturally I liked guitar bands, and I gravitated, of course, towards Morrissey. Oops.

JUSTIN LEWIS

Have you seen that clip from Eight Days a Week? George Michael is on a discussion panel with Morrissey and Tony Blackburn… talking about Joy Division.

Eight Days a Week, BBC2, 25 May 1984. (Since our conversation, the full episode has been uploaded, during which the panel also discusses Everything But the Girl and the film Breakdance.)

‘Wake Me Up Before You Go-Go’ by Wham! had that week entered the UK charts at number 4. The following week it reached number 1. ‘Heaven Knows I’m Miserable’ by The Smiths had been released that week, soon peaking at number ten. At the time Tony Blackburn was broadcasting at BBC Radio 1 and at BBC Radio London. The presenter of Eight Days a Week was The Guardian’s pop music critic Robin Denselow.

JOANNE LIMBURG

And George gets it much better than Morrissey. I don’t think I saw that at the time, but I do remember an interview Wham! did on Radio 1 then, and they were just so funny, and I realised how smart they were. Even if they didn’t wear it on their lyrical sleeve, so to speak.

JUSTIN LEWIS

There are all these hidden things you only spot later. It took me years to clock that the church organ intro on ‘Faith’, which oldies radio always skips now – it’s the melody of Wham!’s ‘Freedom’.

JOANNE LIMBURG

I’ll have to go back and listen. But yeah, at the time, I thought Wham! represented something consumerist and anti-intellectual and airheaded, even though I never thought they were stupid.

JUSTIN LEWIS

No, no. But I think the way the 80s get remembered now – and I like lots of 80s pop – is a bit reductive. It’s all a bit neat for me, most of the politics has been taken out of it.

JOANNE LIMBURG

It wasn’t neat, no. What decade is, when you look at it closely! So I wasn’t sure about them, for reasons that I think had to do with their image, rather than their music, and also because I was a pretentious teenager, and I didn’t appreciate how hard simplicity is. You know, why would I have understood what was clever about what they did?

So, with ‘A Different Corner’, I thought, ‘Oh it’s this guy who presents this soppy image, singing this soppy ballad, it’s all kind of fake. I think I saw Wham! as fake at the time, and this song as another piece of mushy sentiment – and also probably gender comes into it. Not wanting to be a girl liking girls’ music’.

JUSTIN LEWIS

Funnily enough, I remember there was a pressure on me to like ‘boys’ music’, or ‘real music’, whatever that is. The Jam, you know – who I like a lot, but the fanbase could be terribly judgemental. There was a lot of that going on. And with Wham!, I assumed that by this patch, they were aiming at a younger audience than me anyway – though I’m not convinced now that was true.

JOANNE LIMBURG

And I didn’t like the feeling that I was being instructed to have a crush on someone. So I think I probably felt that a response was being mandated for me that I had no intention of giving.

JUSTIN LEWIS

So when do you think your perception of ‘A Different Corner’ changed? It is, to be fair, not an obvious single for anybody to release.

JOANNE LIMBURG

I think it might even have been not long before he died – or since he died. Which I’m ashamed to say. But it was also finding out that he did the whole thing himself. That appealed to me. ‘Oh, how can I make this in a studio?’ I thought: That is my sort of person.

JUSTIN LEWIS

I believe he was the first person to sing, write, record and produce a record entirely by themselves and get to number one in Britain. (Aged twenty-two, by the way.)

JOANNE LIMBURG

I knew none of this at the time. I think I would have immediately been interested if this had been talked about.

JUSTIN LEWIS

Does the Wham! documentary discuss the placing of these two very different records in the context of Wham!’s apparently upbeat catalogue? Because they are completely different in tone.

JOANNE LIMBURG

Well, I think they started writing ‘Careless Whisper’ together very early, as teenagers. But with ‘A Different Corner’ – the thought he’d put into it. You can hear the space in it. The video was just him in almost-empty spaces, and it sounds like space. It sounds like someone in an empty room, and he’s constructed that through sound.

I always appreciate syntactical complexity – you know, ‘Had I been there’. Even in ‘Careless Whisper’ there’s ‘Calls to mind a silver screen’.

JUSTIN LEWIS

And not putting the song title in the chorus. In both those songs, burying it in the second verse.

JOANNE LIMBURG

‘Turned a different corner, and we never would have met, if I could, I would’ – it just breaks your heart. I think it’s a song about very adult emotions, actually. He was very young when he wrote it, but it sounds like quite an old soul song, really, doesn’t it? It’s a desperately, desperately sad song, and it seems extraordinary that at that point in his life, he was writing it, but also putting it out. And number one for three weeks.

JUSTIN LEWIS

And I guess it’s laying the groundwork for the rather different solo career – ‘Cause I’m not planning on going solo’ on ‘Wake Me Up Before You Go-Go’ – where he gradually, slowly disappears from view. He becomes much more enigmatic, with these occasional flashes of doing something. The last album of new original material was as long ago as 2004.

JOANNE LIMBURG

When the whole ‘Outside’ thing happened (1998), that extraordinary way he responded to being outed. ‘Yes, I was out looking for sex. I’m a gay man. A lot of gay men do that. What of it?’ I laugh every time I see the ‘Outside’ video, when he just took the piss out of it. I just thought, ‘You are such a strong-minded, magnificent person.’

——

Joanne Limburg’s The Woman Who Thought Too Much, A Want of Kindness, Small Pieces and Letters to My Weird Sisters are all published by Atlantic Books. She also has another poetry collection due out in 2027, Alas, published by Bloodaxe Books.

For much more on Joanne’s career and books, please see her website: http://joannelimburg.net

You can follow her on Bluesky at @jlimburg.bsky.social.

—-

FLA PLAYLIST 23

Joanne Limburg

(For the time being, this site and project uses Spotify for the conversation playlists, but obviously I disapprove that Spotify doesn’t pay artists and composers properly, and other streaming platforms are available, as are sites to buy downloads and buy recordings. For consistency, you can also listen to the selections via YouTube (where available), and links are provided in each case, below.)

Track 1: BOCK & HARNICK: Fiddler on the Roof: ‘Tradition’

Topol, Original London Cast Recording: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dcn5dUJ6y1I&list=PLbPRxrjG037NU1htyTgYJ4FjXxZHKdd8F&index=1

Track 2: 10CC: ‘Donna’: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SThPj7MPX2o

Track 3: THE TOTS: ‘Please Yourself’: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=T_ZPu6COSsw

Track 4: ELVIS PRESLEY: ‘Way Down’: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=weLSA2vekLA

Track 5: LUDWIG VAN BEETHOVEN: ‘Violin Concerto in D Major, Op. 61: III. Rondo. Allegro’

David Oistrakh, André Cluytens, Orchestre National Radiodiffusion Française: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=d5OJYNmr0gY

Track 6: GABRIELS: ‘Love and Hate in a Different Time’: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-694O6oGWSY

Track 7: BEYONCÉ: ‘Formation’: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OI2jn3lJTAE

Track 8: HILDEGARD VON BINGEN: ‘Ordo Virtutum, Pt. V’

Vox Animae: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KQ6YCIQ8-q0

Track 9: KING CURTIS: ‘Memphis Soul Stew’: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4Sm9n-6hy6M

Track 10: BUGGLES: ‘Video Killed the Radio Star’: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=W8r-tXRLazs

Track 11: BLACK GRAPE: ‘Reverend Black Grape’: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ik9HDX8hJV0

Track 12: GEORGE MICHAEL: ‘A Different Corner’: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IPWHkK-_a_A

Track 13: THE SMITHS: ‘How Soon is Now?’: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OCAdHBrVD2E

Track 14: GEORGE MICHAEL: ‘Outside’: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=62902eXZ8a0