(c) Brant Tilds

The daughter of a flute teacher, the acclaimed and prize-winning composer Cheryl Frances-Hoad was born in Southend and grew up in rural north Essex. Cheryl initially learnt the flute, but soon moved on to the cello, and in the late 1980s, at the age of just eight, secured a place at the Menuhin School in Surrey, which had been founded by Yehudi Menuhin in 1963. Present at her audition was William Pleeth (1916–99), not only one of the most eminent British cellists of the twentieth century, but also the teacher of another much-loved homegrown cellist, Jacqueline du Pré (1945–87).

Cheryl soon became fascinated by composition rather than by performance. In her mid-teens, in the mid-1990s, her life changed when she won the BBC Young Composer of the Year Competition. She went on to study music at Cambridge University, and Kings College, London where she completed a PhD in composition.

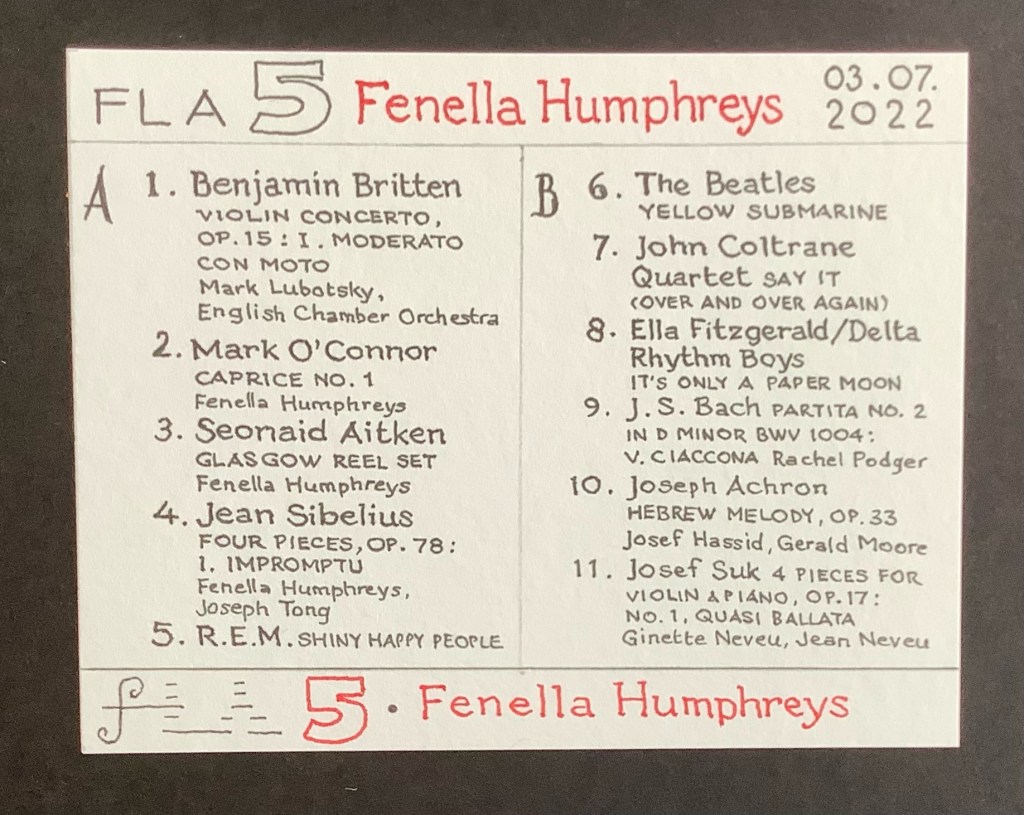

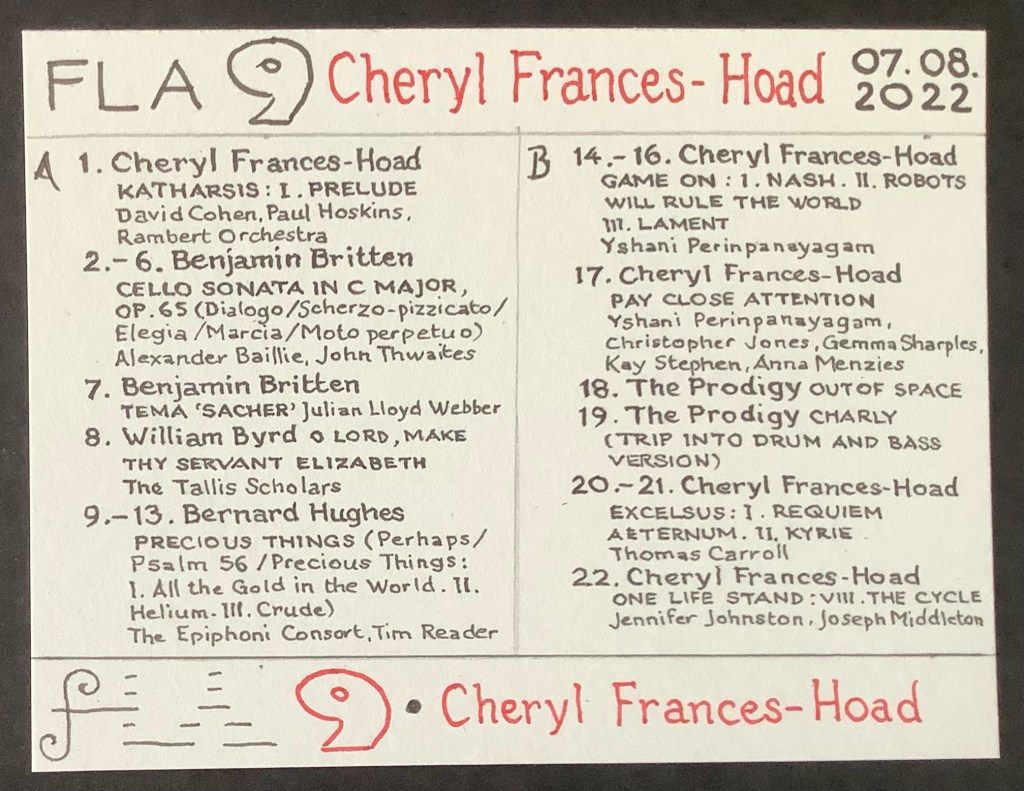

Since then she has written an incredible volume and variety of music for piano, cello, violin, ensembles and orchestras, singers and choirs. Many of these works have been collected on a series of CDs for the Champs Hill label: The Glory Tree: Chamber Works (2011), You Promised Me Everything (2014), Stolen Rhythm (2017), Even You Song (2018), Magic Lantern Tales (2018) and The Whole Earth Dances (2020). Her most recent release is the download Excelsus (2022), a suite for the cellist Thomas Carroll. Others who have recorded her works include the mezzo-soprano Jennifer Johnston, the sopranos Jane Manning and Sophie Daneman, the tenor Nicky Spence, the pianist Yshani Perinpanayagam, the violinist (and previous FLA guest) Fenella Humphreys, the oboist Nicholas Daniel, The Schubert Ensemble, the London Mozart Trio, and the Rambert Orchestra.

Cheryl has won three awards from the Ivors Academy, including – in November 2022 – Songs from the Wild, her song cycle for tenor and chamber orchestra.

I had a delightful and interesting chat with Cheryl in July 2022 over Zoom, while she was based at Merton College, Oxford, where she has been a Visiting Research Fellow in the Creative Arts since 2021.

One of the many things we discussed was her recent commission, ‘Your Servant, Elizabeth’, which was inspired by the text and music of the sixteenth-century English composer William Byrd. The piece was given its world premiere as part of the Platinum Jubilee Prom at the Royal Albert Hall on 22 July 2022 [see links at the end of our conversation], performed by the BBC Singers and BBC Concert Orchestra, conducted by Barry Wordsworth. Previously, Cheryl’s compositions have been given world premieres at the BBC Proms in 2015 and 2017.

As well as discussing Cheryl’s First/Last/Anything selections, we also talked about creativity and inspiration, the melancholy of video game music, why pop and dance music can be an intense form of escapism, and why composing music that’s easy and fun to perform can sometimes be underrated. We hope you enjoy our conversation.

—-

CHERYL FRANCES-HOAD

I didn’t set out wanting to be a composer – I really wanted to be a cellist until I was about fourteen. I think it was just ‘cause I was so shy that it was some way to have some kind of voice, I guess. But when I was fourteen, I wrote the Concertino for Cello, Piano and Percussion, and when that one won a prize at the BBC Young Composer Awards, that, I guess, made me take composition more seriously.

I was still very serious about the cello. But from that point I started being asked to write pieces, and it coincided with also getting things like stage fright. And so I basically stopped practising the cello, and got in quite a lot of trouble for that.

JUSTIN LEWIS

You were still at the Menuhin School at this point?

CHERYL FRANCES-HOAD

Yeah. I rarely, rarely play the cello now. I keep wanting to take it up again and I really should, but I just never get around to it.

JUSTIN LEWIS

I may be assuming an autobiographical element to this, so stop me if I am, but there’s something you wrote called Katharsis, which I gather was influenced by Saturday night talent shows on TV, and I couldn’t help but make the connection of your stopping performing and wanting to be a composer. Did you sense some of the pitfalls that could happen to performers? Was that what inspired that, or were there other factors?

CHERYL FRANCES-HOAD

Bizarrely, that was what David Cohen, who was commissioning it, wanted it to be about. But basically, for years I felt really, really guilty about giving up the cello because the cello was my life, you know? I felt like I’d jilted a parent or a child or something, so that piece was really more based on my life as a cellist and the pieces I played.

There is a minuet with sort of florid cackling wind, which is based on that slightly sycophantic schmoozing you have to do if you want to get a job. I did enjoy that element of it.

——

FIRST: ALEXANDER BAILLIE/PIERS LANE: Shostakovich/Prokofiev: Cello Sonatas (1988, Unicorn-Kanchana)

[Unfortunately, this album is not currently on Spotify or YouTube. If it reappears in the future we’ll link to it. In the meantime, Cheryl as an alternative choice has suggested the following Alexander Baillie recording:]

ALEXANDER BAILLIE / JOHN THWAITES: The British Cello (2017, SOMM Recordings)

Extract: Benjamin Britten: Cello Sonata in C major, Op. 65: I. Dialogo

CHERYL FRANCES-HOAD

Early on, my mum was just amazing at taking me to concerts and buying me music and all that kind of stuff. And she took me to a concert by Alexander Baillie, so I bought that Shostakovich/Prokofiev CD at his concert.

JUSTIN LEWIS

Was that in London?

CHERYL FRANCES-HOAD

No, somewhere really rural. It would have been 1986 or 87. It might have been Haverhill in Suffolk, halfway to Cambridge, which has a really decent venue. I have no memory of the concert whatsoever except that I loved it, and I remember it was my first ever CD and Alexander signed it for me. I remember really loving those pieces. The thing is, I was probably trying and failing to play them at the time. [The disc was] something to inspire me I guess, and it really worked as well as those are some of my favourite pieces to date. You know, for cello they were wonderful. I couldn’t sing them to you now, but if it starts, I still have it from sort of memory. You know, when I was young.

JUSTIN LEWIS

Can you hear inspirations from this music in your own compositions?

CHERYL FRANCES-HOAD

I’ve studied harmony and counterpoint and all that stuff, and musicianship, but because I was composing such a lot, everybody just let me write stuff and I really learned through writing, and all the music I was playing really fed into it. I remember playing some Benjamin Britten when I was eight, a tiny short cello piece called ‘Tema Sacher’ and being really thrilled by that. It was basically all the music I played so I didn’t listen to any music. Because we were too busy practising all the time and playing music. I don’t really remember listening to music at all. It wasn’t like nowadays where people have a piece, and they listen to recordings of several people playing it. I bought a lot of discs of cello music, so I must have listened to this stuff, but the really embarrassing thing is that I rarely listen to music. I always enjoy it when I do but I don’t have a need to do it at all.

JUSTIN LEWIS

That’s logical, though, in a way. When I interviewed Fenella Humphreys for this series, she said that if you’ve been playing music all day and your brain’s been hard at work on it, the last thing you’re going to do is go home and listen to more of it. You might listen to some entirely different kind of music, perhaps. Even for me… I worked in record shops for nearly 10 years when I was younger, and you’d go home sometimes and relish listening to nothing for a bit. If you hear music non-stop all the time, in a weird way, it stops being special.

CHERYL FRANCES-HOAD

Yes, and the problem with being a composer is that you tend to listen to music to get ideas for your own stuff, so I find my mind wandering. I start thinking, ‘I could do that?’

But in answer to your question, basically, my music is connected to Beethoven, Brahms, Bach, Shostakovich, Prokofiev. I feel very connected to that canon, and I want my music to do the same thing that that music does: to move you and engage you, and be satisfying to listen to and to play. Those are my aims, and I feel in line with all those people.

—-

JUSTIN LEWIS

How do you compose then? At the piano?

CHERYL FRANCES-HOAD

I can’t compose without the piano. I’m here at Merton College, we have a drawing board on the piano, on this desk here, and that’s basically it. I’m writing a piece for girls’ choir and organ at the moment, a Magnificat and a Nunc Dimittis for the girls’ choir here at Merton, so I can improvise – once I’ve got one idea, I run with it. With the Magnificat I’m writing at the moment, I’m virtually just improvising and putting it down on paper because I’ve got one idea and I’m just running with it.

But other stuff is much more involved. I’ve got lots of working out for my Prom piece, which is based on a piece by William Byrd called ‘O lord, make Elizabeth thy servant’ [originally composed 1580], and so I really analysed that and things like that, and then copied out the Byrd – and so it depends on the complexities of the piece.

JUSTIN LEWIS

Do you find it starts with a melody or a motif?

CHERYL FRANCES-HOAD

Sometimes. But it can also come from a painting. There’ll be various starting points, but it’s usually sort of like an idea or a mood. Or a colour – I don’t have synaesthesia but I do have vague associations with colour, so if I know there’s a piece about a painting we’ve got very strong colours in, that will sort of give me a starting point. You have a chord, and then, I basically just noodle around on the piano and then if something good comes up then I will of course go back and analyse that, and see how I can develop that. It’s a process of intuition and analysis.

I’m resident at Merton College, Oxford, at the moment, and I’ve written one Magnificat and Nunc Dimittis for the choir. And for that I talked to the assistant chaplain here, as I’m not steeped in the church at all, and he talked me through the Mag and Nunc, and what he felt about it. Some of the things he said just really, really influenced the piece: for instance, the sense of wonder that I think Simeon has in the Nunc Dimittis, and then I just tried to create a chord, that sounded wondrous and that led to the inspiration. I mean, I didn’t actually know that the Nunc Dimittis was representing the experience of a particular person, because I didn’t know its context in the Bible, so that really influenced the solo tenor line at the beginning.

And then, with this girls’ choir I really wanted… I read the surrounding bits of the Bible, where the Magnificat is [in the Gospel of Luke] – and realising that it’s Elizabeth who was with child and Mary is very happy. And so this is a very very cheery Magnificat. ‘For, behold, as soon as the voice of thy salutation sounded in my ears, the infant in my womb leaped for joy.’ So I just thought, I’m gonna do something very jolly about a wriggling baby which just felt right, and I also wanted to write something wriggly in the organ part so I just came up with this motif, and put some stuff over it.

I wanted it to be suitable for the particular constraints of the singers – so, not too many parts, not too much harmony – but I went to hear the girls rehearsing and singing a piece that was very florid, very melodramatic, and they did that really well, so I thought, well, I’ll do that. I wanted to write something appropriate, obviously, with a religious element, but also fun, so thinking about the girls and the girls’ choir… Mary was fairly young, wasn’t she? So to have a more joyful, youthful Mag – you know, why not?

With things like songs, you can just write certain things in. For my Prom piece, I wanted to contrast the two different styles or voices, of Queen Elizabeth and William Byrd. Queen Elizabeth is quite understated, not operatic, so it’s based on the speech rhythms. Whereas William Byrd is much more churchy, because – as I say – it’s based on a piece he wrote called ‘Oh lord, make thy servant Elizabeth our Queen’, and I had to base it on both the text and the music of it, so for that piece there were lots and lots of different influences.

I quite enjoy, with commissions, having very specific briefs. William Byrd is wonderful music, but what can you add to it, you know? Being in that position forces you to be a bit creative. When I was trying to find a way into it, I used some of Queen Elizabeth’s speeches, and listened to 14th century music, but I also read some popular science books, including a book about memory and how memories are formed, which led me to wonder about somebody who has been in the job for so long. Meanwhile, I also looked a lot at William Byrd’s polyphony, so I was going back to trying to work out counterpoint. And then, because I wanted to expand the Byrd, there’s some bits where he has a six-part contrapuntal section, and so I managed to fit in seven parts in one bit, which pleased me, for geeky composer reasons. If you can do six parts I can do seven!

JUSTIN LEWIS

You mentioned that you don’t have a background in religious or church traditions. Is that liberating in a way, for you? I’m trying not to use the word ‘irreverent’, but presumably it means you can bring something different to it.

CHERYL FRANCES-HOAD

Yes, I would hope so. I mean, attending the Menuhin School – would you call it multi-faith? Because it was sort of a faithless school, very secular – because there were people from all over the world from all different backgrounds, and mostly no religions. So I’m very different from the composers who were choirboys, who knew all the psalms by heart. But there are so many very evocative words in religious texts – and that appeals to me.

——

LAST: BERNARD HUGHES: Precious Things: Choral Music (performed by The Epiphoni Consort, Tim Reader) (2022, Delphian Records)

Extract: ‘Perhaps’

CHERYL FRANCES-HOAD

He writes really well for voices so it’s all really singable. I think it’s very original, adventurous but immediate, it can be whimsical and amusing, but also incredibly moving. It has all the things that matter. The first song, ‘Perhaps’, where he writes for children’s voices, it’s a simple tune but it’s a beautiful tune. It’s what I also love about Benjamin Britten – for me it’s emotionally engaging, really well written, idiomatic, and loads of really inventive yet immediate ideas, that really grab you and make you want to listen.

And the Psalm! I love the psalm. ‘Psalm 56’! There’s so many boring settings with psalms that are just so unengaging and dour. But this leaps off the page. I’m not religious myself, but it makes you identify with the text much more than a lot of other [psalms] that are really respected in the canon, you know?

JUSTIN LEWIS

I found a little bit on Bernard’s website where he was talking about the ‘Precious Things’ section, the precious things of which are gold, helium and crude oil. And of course helium is a finite thing, so it ends with this solo soprano who does this sweep to the top of her range as if helium is leaving the planet. It’s brilliant. Not what I was expecting. Classical music can be as surprising as anything.

CHERYL FRANCES-HOAD

It’s amazing to hear that.

JUSTIN LEWIS

Anything is possible!

—–

JUSTIN LEWIS

I obviously wanted to ask you about some of your other work. There’s often quite a lot of playfulness in what you do, like ‘Game On’ for instance, which is for piano and Commodore 64. How did that come about?

CHERYL FRANCES-HOAD

I was a composer-in-residence at Rambert Dance Company, and I got to know the pianist Yshani Perinpanayagam really well. She was really into vintage 80s video games, and I said, Wouldn’t it be fun to do something like that. So we applied for some Arts Council money, and got it!

I mean, I’ve never played video games myself. But there’s something very evocative about it all. We were just chatting, and the first movement (‘Nash’) is sort of based on economics. The Nash equilibrium. I remember watching lots of lectures about it on YouTube from Yale and coming up with these number grids from which I would generate the notes. It’s sort of a fun, different thing to do, really, a different sort of sound world to experiment with. And mainly because Yshani was able to do it.

I wrote the music – she gave me a breakdown of what I could write, but then she programmed it on the Commodore 64. She’s such a brilliant pianist, and she’s always so well-prepared – she did that second movement (‘Robots Will Rule the World’), which is really rhythmically complicated, without a click track. It was an opportunity to explore another sound world. I’ve been wanting to do more electronic stuff for a very long time but basically I never learned it at school because I’d been writing other stuff, and I don’t get round to doing anything musical in my spare time. For the third movement (‘Lament’), Yshani sent me some of her favourite video games. There was a game for the Commodore 64 called ‘XOR’ (1987). You chase a thing around a maze, and it has this 8-bit music…

There’s something really tragic about that music, and I found myself cooking and playing this thing on repeat and singing melodies around it, and I thought it was incredibly moving and emotional. I guess that’s why I like other kinds of music – you find something that really moves you and affects you.

JUSTIN LEWIS

I think on one level, video games (especially old-school ones, for some reason) have these incredibly tragic worlds where the protagonists are just stuck there, forever and ever. It’s ironic that some of them actually use classical themes. ‘In the Hall of the Mountain King’ being used in Manic Miner, for instance, or Tetris for a while used JS Bach’s French Suite No 3. It’s taken more seriously as a genre now. Did you hear Charlie Brooker on Desert Island Discs a few years ago? He chose some video game music: Jonathan Dunn’s ‘Robocop’.

CHERYL FRANCES-HOAD

Did he? And of course there’s a video game Prom this year.

JUSTIN LEWIS

Of course! That’s right. [Broadcast, BBC Four, 05/08/2022] And another piece that you wrote involving Yshani was called ‘Pay Close Attention’, and that leads us nicely into…

—-

ANYTHING: THE PRODIGY/Experience (1992, XL Recordings)

Extract: ‘Out of Space’

JUSTIN LEWIS

I remember I was working in a record shop when the first white label of ‘Charly’ turned up. I was listening to a lot of dance music in those days, some of which was getting more expensive and lavish, and then suddenly this guy in his bedroom has made this crude thing – in a good way. When did you first hear this album?

CHERYL FRANCES-HOAD

When did it come out?

JUSTIN LEWIS

The album came out in ’92.

CHERYL FRANCES-HOAD

I wouldn’t have heard it then. I heard it when I was 16, 17. I don’t know how I got into it. I mean, Keith [Flint] lived very near to me in Essex, so maybe I just heard about it in the news, I can’t remember. But really, what I love about dance music is the way that it just takes over your body. I just went to see the Prodigy, for the first time, actually – and it was great in many ways, although it was the 25th anniversary tour of a much later album (The Fat of the Land) and I prefer Experience. I just love the way the music completely absorbs you, the way you can feel it vibrating through your lungs. I mean, I always have to go with the most high-tech earplugs for my hearing, but I like the immediacy and the way it totally grabs you, I really love that about pop music and dance music. To be honest, if I really want some kind of emotional catharsis, I’d probably listen to more pop music than I would when I’m not looking for subtlety or finesse or complexity. I like the simplicity of it as well, the directness, the sort of trance-like state you can get in. I want to be able to grab people in that way with my music. I like the harmonic directness of it, and the rhythm.

JUSTIN LEWIS

It seems that, in a way, the worlds of pop and classical are closer together than they were. I’ve always followed lots of pop people on Twitter, I suppose because that’s my background, but I’m following more and more classical background people now, and Radio 3 people, and I’ve come back to classical music with a slightly greater understanding than when I was growing up because it didn’t feel like you were being taught about it in quite the right way.

And there was this big divide between pop and classical back then, the two were set against each other. ‘Classical music is staid, it’s slow, it’s for old people.’ And then, from the other side, you got ‘Pop music is tuneless and cheap and meaningless.’ And I didn’t like either stereotype. Those kinds of views seem less common now, or less clearly polarised anyway.

CHERYL FRANCES-HOAD

It’s not so different. Do you think people don’t think classical music is still old and boring? I don’t know.

JUSTIN LEWIS

Hard to say, but I just think people might be introduced to it in a slightly different way now. You have a situation now where Radio 3 and 6Music sort of meet in the middle at times. 6 will play things that verge on ambient or classical, 3 will experiment with electronic and rock a little bit. And Radio 3 did sometimes experiment with the experimental end of pop music, but it feels like it happens more fluidly now.

CHERYL FRANCES-HOAD

That’s a great thing about iPhones and Apple Music playlists, isn’t it?

JUSTIN LEWIS

The possibility of chancing on something, yes.

—-

JUSTIN LEWIS

I’m going to ask you now about some of the specific pieces you’ve written. You’ve just put out the Thomas Carroll ‘Excelsus’ set as a download, which I’ve been loving.

CHERYL FRANCES-HOAD

Oh, thank you.

JUSTIN LEWIS

I discovered that you wrote it back in 2002. I read a quote where you said, ‘I tend to write in the moment’, so how does it feel to revisit something you wrote 20 years ago like this?

CHERYL FRANCES-HOAD

Fine, really! To be honest, I sometimes think the music I wrote back then is better than what I write now! I had been composing for so long by then – I was 21 then, and I’ve been composing since I was eight. So I’m remarkably unworried about my old stuff, it’s so long ago that I can like it for what it is.

It’s very hard [to play], too hard, insanely hard, and I don’t really write music like that anymore… unless it’s for somebody who wants something really difficult. To be honest, that piece is so hard that it doesn’t get done very much. And it sounds amazing on the disc – Thomas just did a fantastic job! But that was back in the day when I thought that performers had nothing to do except practise my music. Then I realised that they did have lives other than stapling themselves to my art! [Laughter] I quite like the seriousness of it, you know. I like it for what it is. Sometimes you just compromise a bit when you’re older, because you realise that something has to be rehearsed in this amount of time, and so you write something that’s easier than it should be sometimes, because you want it to sound good and if it isn’t played brilliantly, it sounds pretty rubbish, right?! I mean, I have had performances of my pieces done which are so difficult, but I sort of admire this sort of uncompromising attitude of that piece, you know?

JUSTIN LEWIS

I think especially when you’re young, it’s about pushing the limits. Which I still think you do, by the way, with music, but there’s different ways of achieving this, I suppose.

CHERYL FRANCES-HOAD

Exactly, and you know when you’re young, at that age, you think that every piece has to be your masterpiece. I still think that every piece has to really express what you want to say, of course. But going back to this girls’ choir Mag and Nunc I’m writing at the moment, my primary concern is that they have a good time singing it. It’s not about my grand artistic statement, right? I want them to enjoy it because they might have to sing some rather dour things, and it would be nice for them to have something fun. But I never would have done something like that in my twenties, when it was all ‘my grand artistic statement’. It’s too tiring to do that all the time.

JUSTIN LEWIS

There are a few compilations of your work out there – did you compile the running orders yourself?

CHERYL FRANCES-HOAD

No, Champs Hill are a charity, and they incredibly generously made the CDs and the promotion of them, they covered that. But I had to raise money to pay for the musicians’ fees and the recording engineers’ fees.

For my first disc, The Glory Tree, which was recorded 2007, maybe 2008, I applied for some funding on a whim and got it – and then I was stuck because I only got half of it, and had to raise the rest of it. Life was a bit hard going at the time, working very hard for very little money, having one performance of everything… I never thought, What’s the point?, but you start to go in that direction. But then, suddenly, the recording was four days of musicians treating my music like it was the most important thing in the world. It was just the most unbelievably affirming thing – and then when the disc came out, it got amazing reviews, back when you got proper broadsheet reviews. And so I became addicted to this experience. But I have spent months and months and months fundraising for those things. I exhausted every funding avenue there was.

JUSTIN LEWIS

You obviously do a lot of background research for your compositions, and your inspirations come not only from history, but art, literature, contemporary events. Do you just get an idea of a story – you read about it, and think, I could write about that?

CHERYL FRANCES-HOAD

Just today, actually, I’ve been in touch with a poet, because I’ve had a little commission for female voices for next year. And I’ve never had the opportunity to set his work before, and so this little three-minute piece has come up, and so he’s stored in my memory bank. I don’t have his books with me here in Oxford, so I just texted him, and said, Do you have any poems that would suit this, this and this? He sent me some, and I really like one, so it’s: Great, I’ll set that!

I wrote a clarinet quintet called ‘Tales of the Invisible’, after I went to this talk at the Presteigne Festival given by this author called Nicholas Murray. He was talking about borders and travelling, and I just had that in the back of my mind.

Often, I just see things on telly, or hear them on the radio. Have you seen that series on BBC, The Art That Made Us? Honestly, that Spong Man at the beginning! I’ve been just obsessed with Spong Man, because he’s just so emotional, right? Looking at that pain in that man, from like thousands of years ago, it’s so striking, and so I have him in the back of my mind. Same with when I went to this talk at the Presteigne Festival given by this author, Nicholas Murray. He was talking about borders and travelling, and that eventually led to me writing a clarinet quintet, called ‘Tales of the Invisible’. And then there was the London Oriana Choir. I was their first composer-in-residence and they wanted to explore the theme of fertility, not a subject that particularly inspires me, so I had to actively try and find poems that inspired me that had something to do with that, tangentially.

Or, for instance, the piece I wrote for the 2021 Three Choirs Festival: ‘Earth Puts Her Colours By’. It was in memory of somebody, a guy who I knew a little about, but had never met. I tried to find a poem that would be suitable, so I got down all the poetry books in my house, and went down a Google trail…. But in the end, the poem I found for that was in the back of one of my mum’s poetry books that she had when she was young. So I do actively search for things to fit certain briefs.

There’s a poster at the train station for the summer exhibition at the Royal Academy of Arts, and I haven’t been to it yet, but the poster is just incredibly beautiful. It’s a jewel of a mouldy lemon. It’s called ‘Bad Lemon’, by Kathleen Ryan.

Basically this artist has done mouldy fruit, but made them out of opals. Staring at this poster, I really want to write a piece inspired by that in some way. But I find being inspired is really easy. You just have to look at something close enough. If I look hard enough at the wood grain of my desk, and the covering in it, you can do something about that.

JUSTIN LEWIS

You don’t strike me as someone who would ever get writer’s block. Or do you?

CHERYL FRANCES-HOAD

No, I haven’t had it for a long time. I had it when I was 15 after I wrote my piece for the BBC Young Composer. I decided that I was writing too fluently and so I tried to plot out what would happen in every five seconds of the music and it just completely stalled me for a year.

JUSTIN LEWIS

Yes, a novelist friend of mine likes starting out not knowing the ending, because if you know too much before you start, part of the fun is gone. Do you find that?

CHERYL FRANCES-HOAD

Yes, I think so. The composer Judith Weir said to me, when she was examining my PhD Viva, ‘Some of the commentary was so pedantic’, because I think I was trying to be intelligent, you know, and prove that I was really thinking academically about all this stuff. And actually, you should just go with the flow of it more. Being here, in this room in Oxford – I’m just writing – and you get paranoid if you’re either not intellectual enough, or not immediate enough. Whereas I’m just writing a hell of a lot of music – I’m very lucky at the moment in that I’m writing full time. The thing is, if you do get stuck, you can just rely on technique for a bit, and then that will inspire you in the end.

JUSTIN LEWIS

And what about ‘One Life Stand’, which was interesting to hear and read about. Which you worked with Sophie Hannah on. It made me think about reinterpretations and new adaptations and also why art continues to be important because you can do something new with it. Because I gather that the original libretto, which I’m not too familiar with, is ‘of its time’, shall we say.

CHERYL FRANCES-HOAD

Of its time, yes! That was with the mezzo-soprano Jennifer Johnston. There’s this beautiful music, by Robert Schumann, from 1840, based on these poems by Adelbert von Chamisso called Frauen-Liebe und Leben (Women’s Lives and Loves) (1830) and I guess what you have to do is believe in the feeling. Because in the last one of the songs, her husband dies, and she says, ‘Well, my life is over’, and obviously nowadays that is old-fashioned, but one can identify with that. But Jennifer was annoyed by singing that song cycle with this beautiful music but the whole focus of the original libretto was getting a husband and having a baby. [So we used the poetry of Sophie Hannah instead.]

JUSTIN LEWIS

In the time you’ve been a professional composer, I’m assuming things have got better for women composers in this country?

CHERYL FRANCES-HOAD

It’s definitely got better. I was really lucky, right? Because I went to the Menuhin School. I was like a chubby ginger kid who was into music and was composing, and it didn’t even occur to me that I was a woman composer. My idol was Benjamin Britten. I just wrote music, I didn’t hear music by a woman composer until I was… twelve or thirteen. But I was in a very specialised environment, so if I could be helpful to teenage girls who feel they need to see somebody who’s like them, that’s great. I’m totally fine with that, and I can see how if you’re not in a music school, or from a minority, that becomes much more important. I’ve certainly benefited from being a woman composer – sometimes with funding that’s only open to women. There are lots of women composers now, and you know there’s so many initiatives to make people more aware of women’s music. I mean, there’s nowhere near equality, but we’ll get there.

——

Much, much more about Cheryl, her career and her music at her website: www.cherylfranceshoad.co.uk.

You can follow Cheryl on Instagram at @cherylhoad, on Facebook at https://www.facebook.com/CherylFrancesHoadComposer, and on Bluesky at @cherylfranceshoad.bsky.social.

The download of Excelsus, performed by the cellist Thomas Carroll, is available from Orchid Classics.

Although the Magnificat and Nunc Dimittis we discussed in our conversation is still work in progress, you can hear an earlier set of Cheryl’s at the following link [Choral Evensong, 28/04/2022, the Merton Canticles, performed by the Merton College Choir]. The Magnificat begins at 15’40”; The Nunc Dimittis at 21’25”.:

Cheryl’s ‘Your Servant, Elizabeth’, while not yet commercially available, was performed and broadcast at the BBC Proms concert event A Royal Music Celebration, live on BBC Radio 3 on 22/07/2022, and televised on BBC Four and iPlayer on 24/07/2022. The concert is no longer on iPlayer, but you can now hear ‘Your Servant, Elizabeth’ here, performed by the BBC Singers with conductor Barry Wordsworth: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Nq_YFw-Vt7c

Gaming Music at the Proms was broadcast on BBC Four on 05/08/2022. Again, this concert is no longer available to watch on iPlayer.

Since my conversation with Cheryl, her Cello Concerto premiered in May 2023 in Glasgow with the soloist Laura van der Heijden, the BBC Scottish Symphony Orchestra and conductor Ryan Wigglesworth. van der Heijden also performed it at the 2024 Proms.

In October 2024, Cheryl was elected Visiting Fellow in Music at Oriel College, Oxford, holding masterclasses with students and composing an anthem for the Chapel Choir to perform, to mark (in 2025) 40 years of women being admitted to the college. She has also been Composer-in-Residence at the Musikdorf Ernen, Switzerland, during 2024-25.

FLA Playlist 9

Cheryl Frances-Hoad

(For the time being, this site and project uses Spotify for the conversation playlists, but obviously I disapprove that Spotify doesn’t pay artists and composers properly, and other streaming platforms are available, as are sites to buy downloads and buy recordings. For consistency, you can also listen to the selections via YouTube (where available), and links are provided in each case, below.)

Track 1: CHERYL FRANCES-HOAD: Katharsis: I. Prelude

David Cohen, Paul Hoskins, Rambert Orchestra: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kor1d08K–M

Tracks 2–6: BENJAMIN BRITTEN: Cello Sonata in C Major, Op. 65

Alexander Baillie, John Thwaites

(Dialogo: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ainTyZGw6CY /

Scherzo-pizzicato: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TBNsy-KShJI /

Elegia: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fIywU6l1kps /

Marcia: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0Ozi2uBTqnQ /

Moto perpetuo: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DTPVSz0icSw )

[NB As mentioned above, Cheryl’s first purchase was actually a disc of Shostakovich and Prokofiev by Alexander Baillie and Piers Lane, but unfortunately, this isn’t currently on Spotify or indeed YouTube, so Cheryl chose another recording by Baillie.]

Track 7: BENJAMIN BRITTEN: Tema “Sacher”

Julian Lloyd Webber: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RYiILyHroYU

Track 8: WILLIAM BYRD: O Lord, Make Thy Servant Elizabeth

The Tallis Scholars: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=E2_cinaHfBs

Tracks 9–13: BERNARD HUGHES: Precious Things

The Epiphoni Consort, Tim Reader

[Perhaps: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SKr4BN2GW_M /

Psalm 56 /

Precious Things:

I. All the gold in the world.

II. Helium.

III. Crude]

(The selections from Bernard Hughes’s Precious Things, apart from ‘Perhaps’ are not currently available on YouTube.)

Tracks 14–16: CHERYL FRANCES-HOAD: Game On

Yshani Perinpanayagam

[I. Nash: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=86GoU64DZmM /

II. Robots Will Rule the World: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Vu3p5HLCC5g /

III. Lament: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mH3vt3-1gAo ]

Track 17: CHERYL FRANCES-HOAD: Pay Close Attention

Yshani Perinpanayagam, Christopher Jones, Gemma Sharples, Kay Stephen, Anna Menzies: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=70aF8YrspGg

Track 18: THE PRODIGY: ‘Out of Space’: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-NJKyBRD7fc

Track 19: THE PRODIGY: ‘Charly (Trip Into Drum and Bass Version)’: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=oRJ607uXA40

[This version not currently available on Spotify]

Tracks 20–21: CHERYL FRANCES-HOAD: Excelsus

Thomas Carroll

[I. Requiem Aeternum: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1SQBkxISNKc /

II. Kyrie: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NP1Ae-vy0M0 ]

Track 22: CHERYL FRANCES-HOAD: One Life Stand

Jennifer Johnston, Joseph Middleton

[VIII. The Cycle: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1g8A4omZJag ]