Michael Gillette is an artist, a true artist. Over the past thirty-five years or so, as a painter, illustrator, cartoonist, designer and creative mind, he has produced a boggling torrent of material – in range and volume – primarily inspired by pop music and pop culture. His clients over the years have included Saint Etienne, Elastica and the Beastie Boys, and his work has appeared in a wide range of newspapers and magazines ranging from Select and Q to The Observer and the New Yorker. If you’ve bought any or all of Ian Fleming’s James Bond novels since 2008, chances are Michael’s done the cover art. But it’s a challenge to summarise that kind of career in a single paragraph, so in the first instance, I urge you to check out his website, michaelgilletteart.com, and a book of some of his many highlights, Drawn in Stereo, published in 2015.

I always sensed Michael would flourish as an artist. The clues were there early on, when we were at junior school in Swansea. Just watching him draw anything was captivating. He was amusing and thoughtful. At the turn of the 1980s, just as the lure of pop history dragged me in, so he’d seen the BBC2 season of Beatles films, and connected profoundly with that pop history’s ultimate figureheads. From then on, for several years, we discussed pop a lot. I now realise this was one of the main reasons to go to school.

At sixteen, Michael moved to Somerset with his family, and then gravitated to Greater London, graduating from art school in the early 90s, and soon finding his skills, talents and wit in considerable demand. As an obsessive reader of the music press and broadsheet newspapers, I saw his work everywhere – and yet somehow still didn’t quite connect this with the talented friend I’d known early on. For reasons that will be explained in the conversation that follows.

The penny dropped when I found Michael’s website in the early 2000s. By then, he was living in San Francisco. We had a long catch-up chat on the phone, and have kept sporadically in touch ever since – and then finally, this year, we had a catch-up in person, in the pub. Which inspired me to ask him if he’d like to do First Last Anything. I was thrilled when he agreed, and so one day in November 2025, we spoke via Zoom: me in Swansea, Michael in St Louis, Missouri, where he now lives with his family. Coming up, amongst other things: what it’s like to house-share with Aphex Twin, the outcome of a commission for Paul McCartney (yes, Paul McCartney), and living and working as an artist and how to share that kind of experience as a teacher and educator.

—-

JUSTIN LEWIS:

So, to begin at the beginning, what music do you remember early on in your home?

MICHAEL GILLETTE:

With mum and dad… Mum was listening to mostly classical music, Schubert’s The Trout, and Holst’s The Planets, I recall… and maybe a few pop albums. The Beatles ‘Red’ and ‘Blue’ albums, and the Greatest Hits of the Carpenters on repeat. Oh! And the The Beach Boys, 20 Golden Greats with an airbrushed painting of a surfer on the front. The musical equivalents of having a dictionary in the house.

Dad, I was not aware of his musical preferences. He saw Gene Vincent and Eddie Cochran play in Birmingham as a teen but in those days, you were only allowed to be a teenager for about fifteen minutes, right? He packed it away. He listened to Jimmy Young who would have been on Radio 2, or Radio 1…

JUSTIN LEWIS:

He was on Radio 1 in the mid-mornings when that started and then around 1973 moved to Radio 2.

MICHAEL GILLETTE:

So it would have been wall-to-wall Radio 2, that’s what I can remember.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

You’d have Terry Wogan on in the morning.

MICHAEL GILLETTE:

Oh yeah, for sure. And apart from that, it was just the homogeneity of the 1970s TV – Top of the Pops for Goalposts.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

It keeps coming up in these conversations for those of us in that generation. And there wasn’t a lot else, really.

—–

FIRST: ABBA: Arrival (1976, Epic Records)

Extract: ‘Tiger’

JUSTIN LEWIS:

We had this album as well in the house, although I think my dad borrowed it off someone for a while. But we were playing it a lot. But I remember coming to your house at the time and you had this album, along with – if I remember correctly – the first Muppet Show album.

MICHAEL GILLETTE:

Yeah, that makes sense.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

Which we put on. So how did you come to Arrival, then?

MICHAEL GILLETTE:

I think I had it for my seventh birthday, so I must have asked for it. I just think it was in the culture: Look-In, posters on the wall etc.. I’m sure they were on Seaside Special and things like that. Unavoidable, right? Utterly fantastic. And immediately sticky [laughs].

JUSTIN LEWIS:

The people who are ten years older than us thought ABBA were ridiculous.

MICHAEL GILLETTE:

They must be deaf.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

Because, firstly, ‘it’s Europe’ and unless it was Kraftwerk, no pop from Europe was meant to be any good, apparently. And then punk rock happened in Britain, even though ABBA were already making brilliant singles, and the Sex Pistols liked ABBA, for instance. And subsequently, there was a critical revival with ABBA – I remember Elvis Costello saying of ‘Oliver’s Army’… I’m sure you know this…

MICHAEL GILLETTE:

You can hear it – the piano.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

He used to cover ‘Knowing Me Knowing You’, live.

—–

JUSTIN LEWIS:

Towards the end of junior school – so this is 1980, 1981 – I remember two or three massive Beatles fans in our year, and you were one of them, and I remember talking to you about it. So you had the ‘Red’ and the ‘Blue’ albums in your house, but what was the next step for you with Beatles fandom?

MICHAEL GILLETTE:

Aw – BBC, Christmas 1979 – they showed all the films. I remember the Shea Stadium one, and especially Magical Mystery Tour…

JUSTIN LEWIS:

Which I don’t think had been on since the first showings [over Christmas 1967 – once on BBC1 which was still monochrome, and days later on BBC2 which had just begun broadcasting in colour].

MICHAEL GILLETTE:

I remember watching that in my grandparents’ house in my Cub Scout uniform [Friday 21 December 1979, BBC2, 6.10–7.00pm], and looking at it – because there’s a bit with a stripper in it which I was watching via a convex mirror because I thought ‘I can’t just turn around and watch this!’

That Christmas was the introduction, really.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

You having your Cub Scout uniform on suggests we must have been to some Cub event, because we were in the same pack. I’m trying to think what that might have been.

[The other showings of Beatles films that Christmas:

Sat 22/12/79, BBC2 1835–2000: Help!

Sun 23/12/79, BBC2, 1740–1830: The Beatles at Shea Stadium [first showing since 1966]

Mon 24/12/79, BBC2, 1740–1900: Yellow Submarine

Tue 25/12/79, BBC2, 1500–1625: A Hard Day’s Night

Wed 26/12/79, BBC2, 1750–1910: Let It Be]

MICHAEL GILLETTE:

They just made me never want to wear a uniform again. It sparked off something :‘What on Earth is this? How do people get to live like this?’ It was the whole package – to see the comedy and the style. I’ve always had these two things together – visual/musical – and seeing them [together] made a massive difference. No regular job plans after that.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

One of the themes of your career, really, is how you’ve channelled pop music into artwork, but with the Beatles, I feel as if you’ve particularly latched on to the fantasy and mythology over the reality of them. I’m not suggesting you haven’t studied the latter! But it’s about setting the imagination free, and Magical Mystery Tour certainly encourages that. As much as something like Get Back would show them making a record in real time, you get this other side to them which has them having adventures. Like they’re comic book characters.

MICHAEL GILLETTE:

Yeah. Perfect for children, as a gateway. It was the scarcity of it. Even though it was on at Christmas that year, after that, it was gone. Until John Lennon died.

Just before he died [December 1980], I remember you used to write the charts out every week, and I saw that John Lennon was in with ‘Starting Over’, [a brand-new single]. And I was like, ‘What do you mean, John Lennon’s got a new single out?’ When I heard it, I couldn’t equate it with The Beatles, it seemed like a dimmed bulb. So when he died, part of me felt, ‘Oh great, The Beatles are now everywhere!’ I was spending all my pocket money on everything I could get, all that merchandise that appeared! It’s a terrible way to think about it really.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

But he’d also been away for five years, of course, prior to that single, which is a long time. And were you a John fan or a Paul fan?

MICHAEL GILLETTE:

I didn’t know who sang what until later. When I started buying their records, I would look for the albums with the least amount of music that I already knew, to get the best value out of it. The first one I bought was Revolver.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

Funnily enough, the critic David Quantick once pointed out [on the superlative Beatles podcast, Chris Shaw’s I Am the Eggpod] that Revolver (along with the ‘White Album’) is probably the least well represented album on ‘Red’ and ‘Blue’.

MICHAEL GILLETTE:

Yeah, that’s why I would have bought it. ‘She Said, She Said’ – that song really opened things up for me, it’s in my DNA. I don’t think Paul McCartney’s even on that song.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

An enduring Beatles mystery, so many conflicting accounts and fragments of evidence.

MICHAEL GILLETTE:

I read a lot of philosophy and psychology. Partly it’s helped me understand and justify pop’s importance rather than its triviality. Pop’s taken up a lot of my bandwidth!

I learnt a lot from René Girard, who, as an anthropologist at Stanford in the eighties, coined theories around mimetic desire. We’re all porous to suggestions and mimic others. We desire what other people desire. We can also hate what other people desire. This causes tribalism and scapegoatism. Girard’s warnings are important because many Silicon Valley bros, including Peter Thiel, took his class. They saw his cautions as business models. Look at how that’s played out with social media…

Anyhow, I thought, ‘oh, this is kind of what happened to me with the Beatles and pop music.’ The Sergeant Pepper cover – it’s a mimetic map of culture, religion, art, everything. Probably 90 per cent of my interests all connect back to the Beatles. Ultra mimetic.

We both grew up during the high watermark of youth cults [JL agrees]… music with distinct looks and styles…These are explained by mimetic theory too. We were kind of outside it in Wales – couldn’t get the right clothes [laughs], but it saturated those impressionable years for our generation, right?

JUSTIN LEWIS:

Yeah – you’d look at London or Manchester and you’d think, ‘How do you get to go there then, a city where it’s all happening?’ Because nice beaches that there are, amazing coastline, Swansea didn’t really have that kind of magic. Bands didn’t come very often, and it wasn’t easy to go and see people if you were under eighteen.

MICHAEL GILLETTE:

Billy Bragg I managed to see in Swansea, a miners benefit gig [7 April 1985 – Easter Sunday, in fact]. At the Penyrheol Leisure Centre. I saw The Alarm there too [16 November 1987].

JUSTIN LEWIS:

Just before we move on from The Beatles, though I’m sure we won’t move too far, can you tell the story about your Paul McCartney album sleeve commission? Because this is extraordinary.

MICHAEL GILLETTE:

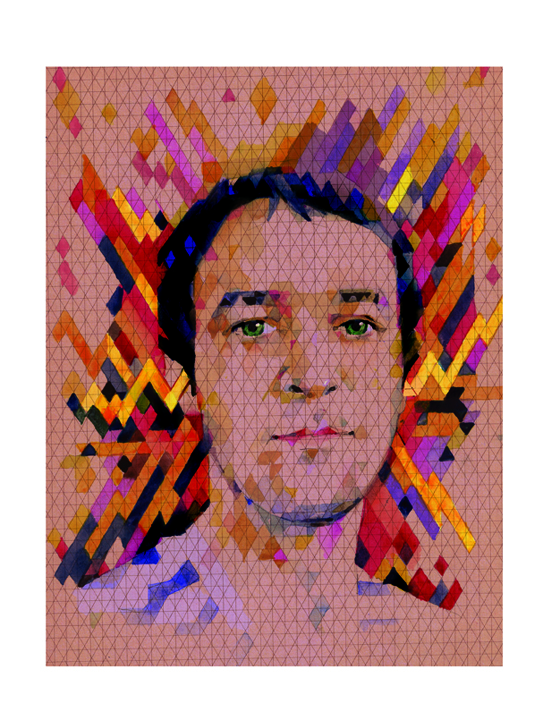

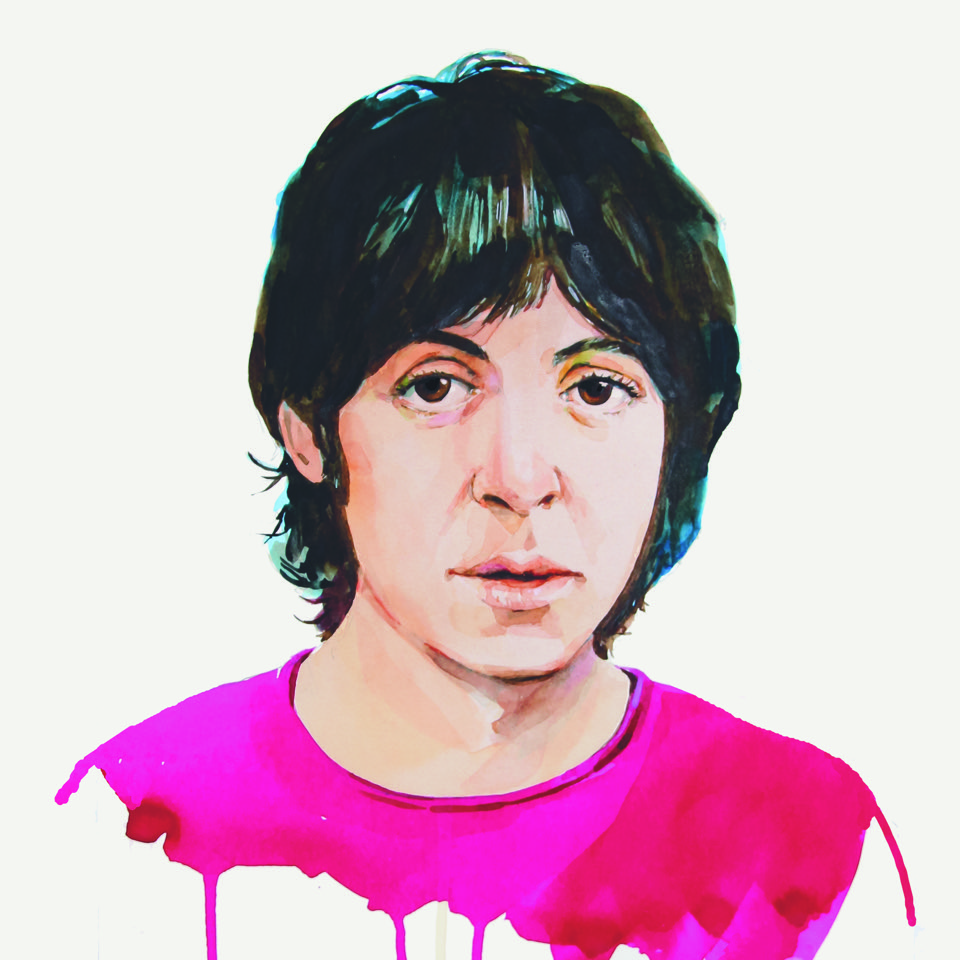

I’d done some work for the Beastie Boys, an animation for their [To the 5 Boroughs] tour (2004/05). They were signed to Capitol Records. The lady I was dealing with there rang me one Friday afternoon, and said, ‘Paul McCartney is coming in on Monday and we’re going to do a “Greatest Love Hits” – for the first time, a compilation of his Beatles and post-Beatles work.’ They were very specific: ‘We want him doe-eyed and lovely, from ’67, ’68…’ I was like, ‘Can do.’ So I worked over that weekend, so confused at how this had happened. Anyway, I did it, and the next week they got back to me: ‘Oh he’s just come in, and no Love album for him, he’s getting divorced.’ So that was the end of it. They said, ‘Oh he says it’s really great, he really likes it!’ They tried to buy the artwork. That was the closest brush with my obsession.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

I knew you as a brilliant artist even at school, but what sort of sleeve art was inspiring you back then?

MICHAEL GILLETTE:

Well, anything to do with the Beatles!, so, Klaus Voorman, Peter Blake and then Richard Hamilton – there’s three. My mum would buy me bargain bin books from WHSmiths in Swansea. One of the first was a Rick Griffin monograph. He was one of the San Francisco psychedelic hippy poster artists – all imagery inspired by music. Another was by the artist David Oxtoby, Oxtoby’s Rockers. He was a contemporary of David Hockney, from Bradford. He did incredible paintings of rock stars. I was twelve and had chicken pox when I got it – after two weeks off school itchily looking at this book, this massive door had opened in my mind. I thought, ‘Oh, this is also possible’ [laughs].

When I eventually visited San Francisco for the first time in 1997, the posters of the ‘60s had acted as sirens. I ended up living just a couple of streets away from where Griffin made most of his famous work in the late sixties. I used to pass his old house every day. He was long gone by then. He died in a motorbike accident in the 1990s, he’d been doing covers for The Cult just previously. He became a born-again Christian in 1969 and moved down to Southern California and became a massive influence in that world. An amazing character.

—–

JUSTIN LEWIS:

I’m going to quote from your excellent collection of artwork, Drawn in Stereo. ‘Art wasn’t my first career choice. I wanted to be a pop star.’ Now, I knew you were a good guitarist, that’s what I remember, but I hadn’t quite realised you had that in mind, so I was quite surprised to read that.

MICHAEL GILLETTE:

Yeah, I wasn’t that good at music. When we moved to Somerset, I did my art foundation year in Taunton. The West Country had a good music scene. PJ Harvey came out of that time and place. In Taunton, bands were everywhere… When I got to Kingston Art School, no-one was interested in forming groups. Disappointing. The thing about getting into colleges that are ‘good’ is people are focused on the job at hand! I wasn’t. I was in a band for the first year… but I just knew: Nope – you don’t got it.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

The thing about being in a band – maybe even if you’re a solo artist – is there’s a career arc you’re expected to follow, and it’s all about compromise. Whereas if you’re an artist, you can surprise yourself. You’ve got the freedom to be inventive. And it seems to me, given what you’ve gone on to do, you’ve just kept changing. You’ve never stuck to one thing for too long.

MICHAEL GILLETTE:

I was reared on that Beatles or Bowie [arc] to keep changing and evolving. The visual side of music is such a rich seam to mine – you can tap into two completely disparate things like, say, two-tone and psychedelia and evolve something fresh. But yeah, you’re right. It’s a control thing, and you don’t have that in a band. I didn’t much enjoy being on stage. I got very nervous, I’d play real fast.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

Were you trying to write songs, by the way?

MICHAEL GILLETTE:

A bit, with bands, but I didn’t have that gift on my own. I thought I would join a successful band at art school. Instead, I graduated off a cliff. At the end of Kingston, in ’92, some student friends knew Richard – the Aphex Twin and we all moved to Islington together. I didn’t know his music at the time, but holy WOW!

JUSTIN LEWIS:

The first time I heard him, that first album [Selected Ambient Works 85–92, 1992]: ‘What the hell is that?’ I was listening to quite a lot of electronic music at the time, but that felt like a real departure from everything.

MICHAEL GILLETTE:

I knew he was groundbreaking – anyone with half a tin ear could tell that. I think the groups I was involved with, during Britpop, were fantastic fun, but there was already so much of the guitar pop canon established. Richard was off the maps making his own worlds.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

Yes, I love Blur, but… a lot of it was good pastiche, but pastiche nonetheless.

MICHAEL GILLETTE:

I can understand pastiche, I personally don’t re-invent the wheel, I just put new rims on.

Oasis… I never saw them as Beatles-like, more Slade in Cagoules.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

But they weren’t going to reinvent themselves with every record like the Beatles did. We’ll come back to Aphex Twin in a second, but I just wanted to ask you about something else that happened in summer ‘92 when you’d just graduated from Kingston. You stuff an envelope of your stuff through the letterbox of Saint Etienne’s house in north London. I know that you’d really enjoyed Foxbase Alpha, their first album, but what made you think of choosing them to approach?

MICHAEL GILLETTE:

When did that album come out?

JUSTIN LEWIS:

October ’91. I remember I bought it the day it came out.

MICHAEL GILLETTE:

Okay, I must have too. In late 1991, I was in Russia on a month-long student exchange, I had it on tape, and listened to it there. That album’s very atmospheric and kaleidoscopic – it fit Moscow. Back in London, I listened to it driving around, it fit there too. ‘Nothing Can Stop Us’, what a fantastic song. Bob Stanley told me they paid £1,000 to clear the Dusty Springfield sample. Money very well spent.

Meanwhile, I fell out of Kingston. I wasn’t ready to leave college, I’d been expecting to do an MA – at the Royal College of Art, but they passed. In that last month of Kingston, I realised I’d better start approaching people. It was almost a desperate thing. I knew Saint Etienne were working on another album. But there was some magic involved, definitely – Foxbase Alpha, finding their home address on the back of the ‘Join Our Club’ single, picking them to stalk … They understood my fandom.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

Yeah, that first album, in the booklet, you’ve got all these photographs of icons, so Micky Dolenz is there, Billy Fury, Marianne Faithfull… Eight or nine of them.

MICHAEL GILLETTE:

It’s another mimetic gateway. The glamour of formica caffs that’s open to all. It wasn’t like the eighties, where you needed a zillion dollars to go into the studio and make some shit, atmosphere-free record; all boxy drums and Next suits with padded shoulders. Instead, it was the longings of the fan, lost treasures and pop theories. That record has a dreamy hiraeth.

I stuffed that envelope through the letterbox, went back to Surbiton for the last couple of weeks college. Next, I went up to Heavenly, their record company, rang the bell. Martin Kelly, their manager, opened the door and said, ‘Oh, they told me about you. Come on up!’ I thought, ‘My god, it’s this easy?! This is great! Is this how it’s going to work?’ And of course it doesn’t often work like that. Magic was afoot. You have to knock though.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

They’ve always been very interested in the contemporary, but shot through with something of the past at the time.

MICHAEL GILLETTE:

Yeah. Reinterpreting the past, excavating and curating. Bob Stanley was like meeting an older cousin who knew everything about pop. So anyway, that’s what happened, and they paid me £2,000 which was a lot of money straight out of college. I didn’t see money like that again for a long time.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

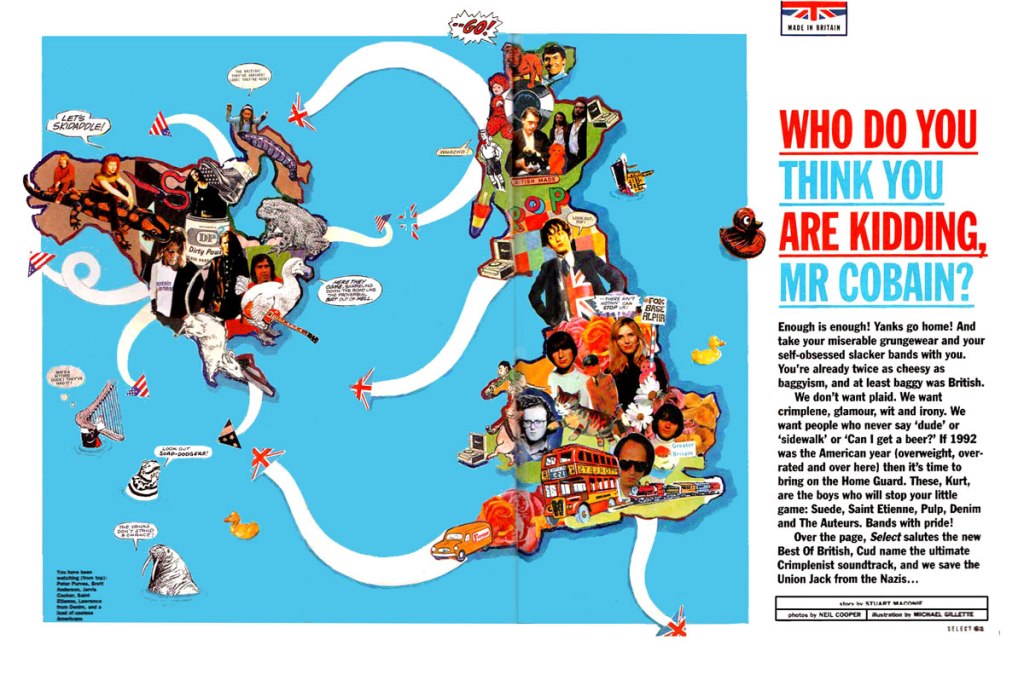

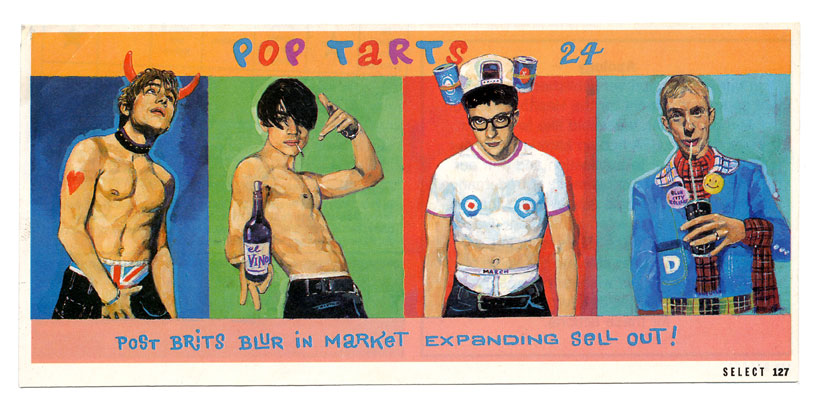

And then you started to do bits for Select magazine, right? Which was a sort of indie-dance version of Q magazine, for those who may not remember.

MICHAEL GILLETTE:

My flatmate Stu’s brother [Andrew Harrison] was the editor of Select. Andrew had a ‘no nepotism’ rule, he couldn’t be seen giving jobs for the boys. But when he found out I’d worked for Saint Etienne, he was like, ‘You must be bona fide.’ So that’s how I got the job doing the illustration for the Stuart Maconie article about Britpop [Select, April 1993 issue].

JUSTIN LEWIS:

And then you did this regular feature called Pop Tarts, every month, and it’s reminded me how much you made me laugh in schooldays. Because you found room for humour and irreverence as well in many of these pieces.

MICHAEL GILLETTE:

Definitely. When I left college, I was a headless chicken, didn’t know what to do, and was thinking, ‘I’m only going to make serious work, try and do stuff for Faber & Faber’. Then I thought: ‘That’s not who I am – humour is really important.’ That’s yet another lesson from the Beatles – they could reach the highest rung of an artform and still be silly. I can’t bear serious pretension – when the scene gets pretentious, I get really uncomfortable. I did fifty Pop Tarts. By ’96 I couldn’t take it anymore, but it was a good calling card for a while.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

That might be the longest-running thing you’ve ever done, then.

MICHAEL GILLETTE:

It probably is, yeah.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

And then you’re doing newspaper commissions, you’re in a lot of the broadsheets in the late nineties, doing accompanying illustrations for things. I found a thing in the Telegraph archive of all places, a culinary feature.

MICHAEL GILLETTE:

I did The Observer for a year, too. I did their back page column called ‘Americana’. Louis Theroux wrote many of the articles. I came back to London this last summer, went to Bar Italia, and there’s a drawing I did – maybe for the Telegraph – framed on the back wall! It was about Italian clothes culture, and I had decided to include Bar Italia. Not a work of genius, but when I saw it, I was thrilled [laughs]. I couldn’t think of a better place to hang!

JUSTIN LEWIS:

How do you feel in general now, seeing work you did thirty years ago or longer?

MICHAEL GILLETTE:

I’m just glad to be alive, and to have been able to make a creative living. Sometimes I have barely any recall of pieces – the Bar Italia picture for example. I’ve made so much stuff, it’s a rodeo schedule. I chose pop media – magazines, books, records, videos – rather than gallery art where ten people might see it. I wanted to be seen. It’s a really proletarian art form. Masses of art for the masses.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

Your stuff did get everywhere, and I saw a lot of it, although somehow I didn’t make the connection that it actually was you for some time. I should explain here that your surname has grown an extra ‘e’ at the end since we were at school.

MICHAEL GILLETTE:

Either Select added that to my name or maybe Saint Etienne.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

Was it in error?

MICHAEL GILLETTE:

It was, yeah. But I wasn’t going to argue with that. I just let it go. Everyone was dropping Es in the nineties. I picked one up.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

So what did you do for Saint Etienne’s So Tough album? You certainly came up with the logo, right? And you designed the cover?

MICHAEL GILLETTE:

I initially did a painting of the 1970s photo of Sarah, which her father took. They went with his photo for the cover, which was the right decision. I did paintings of Bob and Pete for the inner sleeve. I wasn’t match fit yet. I hadn’t advanced much at college. I comped together some logos and they went with one set in a font called Bunny Ears.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

And that was the logo they used when they first went on Top of the Pops, for ‘You’re in a Bad Way’.

MICHAEL GILLETTE:

I was so excited: ‘My logo is up there.’ A little bit of me is on TOTP.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

So, with Aphex Twin, you were living in the same house around this time, 1992–95, three years or so. Was that a creative environment, a chaotic one, or both?

MICHAEL GILLETTE:

Both, definitely. We lived in two different locations. In the first one, he and his girlfriend lived above us. So my introduction to him was through the floorboards, really. He was right above my bedroom, it would be very quiet for long periods of time, when he was listening through headphones making stuff, and then it would be uproariously loud and sometimes terrifying, sometimes beautiful.

Then we moved to Stoke Newington and he had a tiny studio in the midst of the flat, so there was no separation. There were a lot of people coming and going, hangers on, and basic early twenties bad behaviour from young creative types. We all wore each other out because we were so much in each other’s pockets. But everybody was interesting and funny. And for all that people think of Richard, he was not a pretentious human being.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

I always think there’s quite a lot of humour in what he does anyway.

MICHAEL GILLETTE:

Yeah, often puerile!

JUSTIN LEWIS:

How did his remix for Saint Etienne’s ‘Who Do You Think You Are?’ come about? Is it true you were a sort of messenger with that?

MICHAEL GILLETTE:

I asked him, yeah. I hadn’t known him for long – and I wouldn’t say I had the capability to sway him in any way, but he was open to doing stuff at that time. I think he did a good job.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

I find it quite funny he did it, given the choice of song. Because I can imagine him being offered ‘Avenue’ to remix, for instance, but ‘Who Do You Think You Are’ (nothing to do with the Spice Girls by the way, this was earlier!) was a cover version of a song recorded by the Opportunity Knocks-winning comedy showband Candlewick Green in 1974, and the Saint Etienne remake had the potential to be a huge hit. And it’s not a remix you’d expect from a commercial single at all. But then Saint Etienne were great at being leftfield pop stars.

MICHAEL GILLETTE:

I’m sure they were elated with that remix. I don’t think they were looking for a Fatboy Slim banging track.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

And you did some video work for Elastica too.

MICHAEL GILLETTE:

I did two animations for their videos, which was very stressful, and some sleeve work for them too.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

The ‘Connection’ single.

MICHAEL GILLETTE:

I did a painting for that, so I saw them from lift off to stratosphere. Justine [Frischmann] moved to Northern California in the noughties. We wound up living in the same neighbourhood – she helped us out to move there after we left San Francisco, so that was an enduring connection from that time.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

In 1997-ish, you finally got to visit San Francisco because, as I understand it, you had a show on at the Groucho Club in London and lots of wealthy people bought lots of your work, and so you could afford to go. Is that true?

MICHAEL GILLETTE:

Yes, that is exactly what happened. I had a show at the Groucho the same week that Labour were elected – a high watermark and possible end of Britpop – and I sold 14 out of 20 pictures.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

And Jarvis Cocker bought one?

MICHAEL GILLETTE:

Well, you know Ant Genn? He played with Elastica, he’d been in Pulp [and now writes scores for film and TV, including Peaky Blinders]. He bought three, one of which was for Jarvis, but Jarvis ended up paying for all three. I don’t know why. Who else bought one? Graham Linehan, who was then working at Select, Damon Hirst’s manager…’90s Soho.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

Do you ever miss Britain? You’ve been living in America a long time now.

MICHAEL GILLETTE:

Yeah, twenty-four years. Pound for pound, Britain punches harder than anywhere else. Music, comedy, history… I do love it. I feel a bit claustrophobic there now. I wish I’d spent more time visiting antiquity. I guess you always want what you haven’t got, right? Here, I want something pre-Victorian. I want to get my hands on something ancient!

—–

LAST: THE LEMON TWIGS: ‘Ghost Run Free’ [2023, from Everything Harmony album, Captured Tracks Records]

JUSTIN LEWIS:

Lemon Twigs have come up before on this series, and rightly so [FLA 24, Alison Eales]. What was it about ‘Ghost Run Free’ in particular?

MICHAEL GILLETTE:

Well, it’s like the offspring of The La’s and Big Star, isn’t it? I’d adopt that kid and bring them up as my own. Just instant ear candy, pressing all my buttons. I’ve played that song a lot – I like the rest of the album, but something about that song absolutely chimes. I was lucky to see them play here in St Louis – people tend to skip over the Midwest. I decided to wear a hat and stand at the back, not to spoil the kids’ fun. But the audience were all older than me! It was almost like a vampiric ritual… the band’s so young, what must it be like for them, looking out at the Night of the Living Gen Xers?

JUSTIN LEWIS:

It’s a breath of fresh air, this album, and while there’s lots of stuff I like at the moment, you don’t tend to get things that are big on chords, harmonies or melodies charting particularly highly. It’s unusually tuneful – the last time they got picked on this, I was referencing early seventies Beach Boys and Todd Rundgren, but now I can also hear Crosby Stills Nash and Young in it, even Roy Wood’s Wizzard.

MICHAEL GILLETTE:

They can all play, the band’s been together a while. They look like they were made in a pop culture laboratory. Live, they’re all swapping instruments. And then you’ve got the two D’Addario brothers, like the Everlys, Kinks or the Bee Gees. I’m going to quote Noel Gallagher here – ‘brothers singing is an instrument you can’t buy in a shop’. Like ABBA, where harmony and melody is absolutely everything. There’s always a chorus with multiple voices, so you feel like you’re included in the song. That’s one of Brian Eno’s pop observations/recipes.

Most songs I really love have got harmonies. Apart from The Smiths – I don’t know why they never had that.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

That’s a good point. I suppose with them, the harmonies are in the guitars.

MICHAEL GILLETTE:

Yeah, but Johnny Marr can sing – he’s got a good voice. Why did they never sing together? I suppose Morrissey won’t share his crisps.

—–

ANYTHING: JOHN O’CONOR: Nocturnes of John Field [1990, Telarc/Concord Records]

Extract: ‘Nocturne #1 in E flat Major’

MICHAEL GILLETTE:

I came to a point where pop music was just frazzling me. To quote that ‘Alfred Prufrock’ poem by TS Eliot: ‘I’ve measured my life out in coffee spoons’, whereas I’ve measured my life out in poppy tunes. There just came a time, especially working and reading, for [something else] and hearing these Nocturnes…

JUSTIN LEWIS:

What sort of age were you?

MICHAEL GILLETTE:

Oh, late forties. I’d always listened and worked to lots of soundtrack stuff, John Barry, Lalo Schifrin… But here, just the solo piano is so peaceful. Going from a world where I know everything about a musician, to this, where I didn’t know anything. I just listened without any baggage – a blank slate.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

Can you remember how you came across it, then?

MICHAEL GILLETTE:

I really don’t know. Maybe through YouTube’s algorithms… do you know anything about John Field? [Born in Dublin, 1782, lived till 1837] He had a riotous life. He was basically a rock star. His life would make a great film, Barry Lyndon-esque. Eventually I looked him up, but for years I knew nothing but the music.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

I knew the name, but it transpires he invented the nocturne form. Chopin was a fan. So he’s an innovator.

MICHAEL GILLETTE:

Yeah, I’m no connoisseur. I’ve listened to Chopin’s Nocturnes, I don’t enjoy them as much. Satie’s are good too, but Field’s are like an instant warm bath, reliably calming.

I’ve been thinking about the Aphex Twin this last couple of weeks because one of my students at college was drawing his logo over and over.

‘Oh, the Aphex Twin,’ I said.

‘Do you know that guy?’

‘Actually, yeah, I do know that guy.’

Then yesterday, my screen printer was wearing a homemade Aphex Twin T-shirt, with a picture of Richard in the Stoke Newington house studio. I’ve found folks want to keep the mystique of him intact. We are so overloaded with information. I think the mystery allows for purer engagement.

I feel like that about classical music. I won’t reach the point where I need to know what the third horn player had for his tea and how that affected anything. You know what I mean?

JUSTIN LEWIS:

When we were at school, the running joke about pop trivia knowing no bounds would be ‘What colour socks was Paul McCartney wearing when they recorded “Get Back”’?, and now the Get Back film exists, you can bloody well find out! It’s ridiculous really. I suppose thirty, forty years of reading the pop music press has created this frame of mind, and you can’t do that with everything. One of the nice things about new music now is I often come to things and I don’t know anything about them, who they are, nothing beyond the bare bones. It’s like being eight again.

MICHAEL GILLETTE:

It is. What I see with my children is they’re not interested in context, it’s all delivered scrolling on a phone. Recently, my daughter learnt to play ‘Love Grows Where My Rosemary Goes’ on the violin, and I asked:

‘How do you know that song?’

‘Instagram… How do you know it?’

‘It’s from the late 1960s.’

‘Oh I thought it was new.’

It’s trending audio… stuck behind reels. Folks use trending audio, and the algorithm boosts the post. It’s kinda greasy. My daughter was humming ‘Golden Brown’’, same thing – it’s used on medieval themed reels.

We were groomed [laughs] to be obsessed with pop minutiae. Now, it’s just another bit of content in the feed. They do introduce me to some new music though, Olivia Rodrigo I enjoy.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

Well, we were in the analogue age where knowledge was difficult to come by, so you’d collect fragments of information until you had far too much of it all. [Laughs] That’s what happened.

MICHAEL GILLETTE:

YES! – the scarcity back in the day. So maybe what I’m trying to do with jazz and classical music is to go back to pre-knowledge. I love Lou Donaldson, I love his music, but I wouldn’t know him from… Donald Duck. I know he’s Mr Shing-a-Ling. But I don’t really have any interest beyond listening and enjoying.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

And it makes it more random, you can make your own connections with it. For a long time, we got used to other people shaping music history, and now I guess you can create your own experience.

MICHAEL GILLETTE:

Totally. That’s the big difference. When you used to bring Smash Hits in to school, and we’d pore over it at lunchtime, Mark Ellen was the editor at the time. That Britpop illustration I mentioned earlier… Mark Ellen [by 1993, the Managing Editor of Select] was who I handed it over to. Did the obsession bring that to pass? I suppose what you give your attention to grows.

—-

JUSTIN LEWIS:

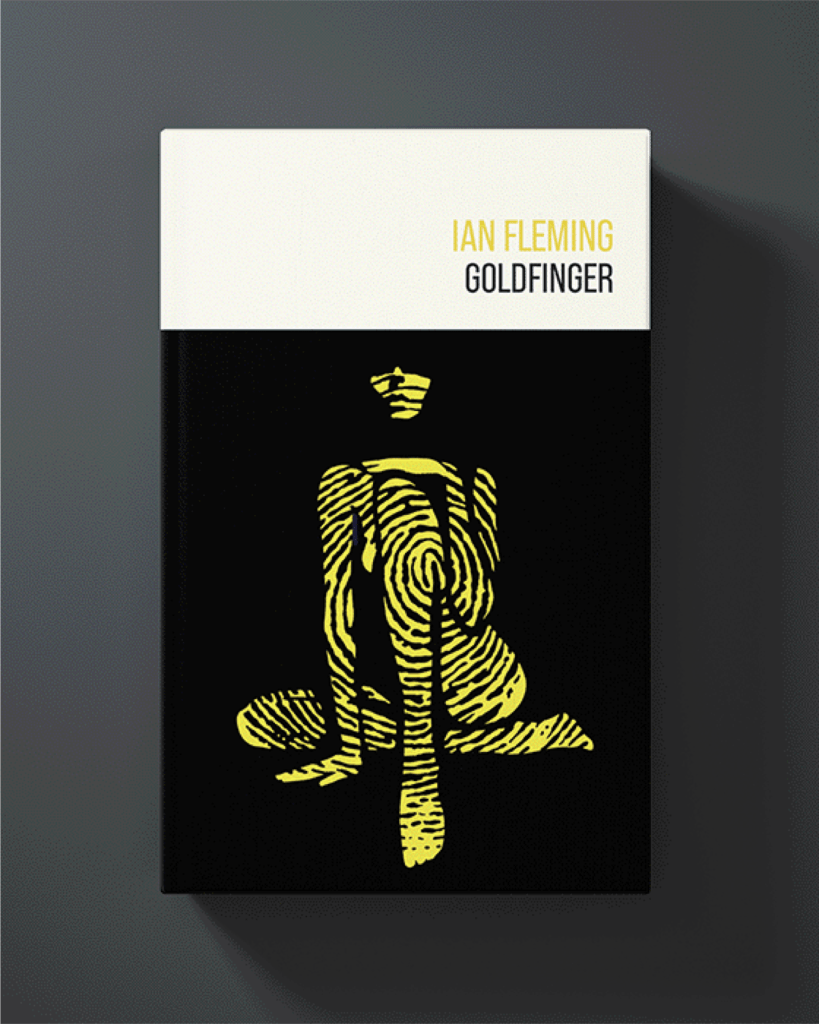

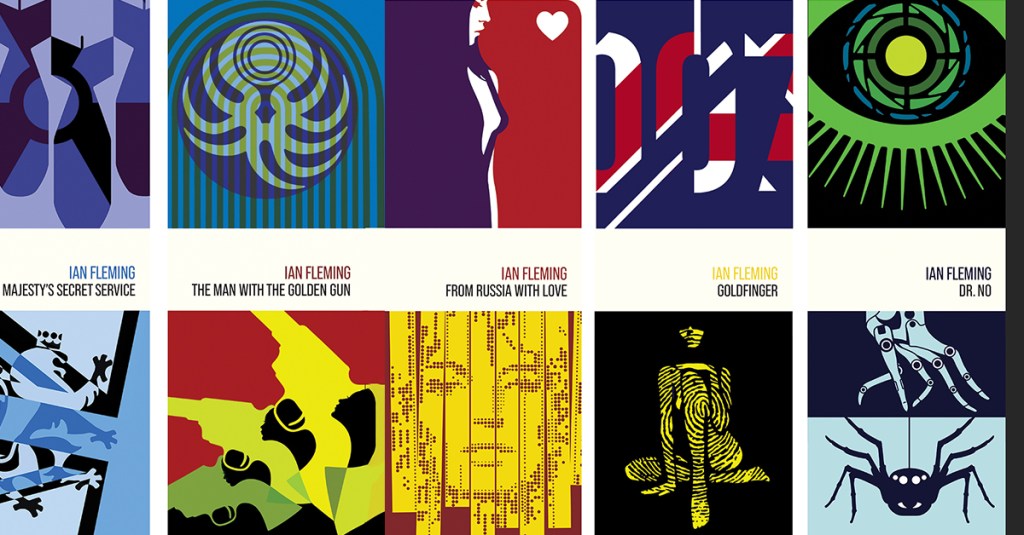

You’ve designed [in 2008 and again in 2024] two very differently styled series of covers for Ian Fleming’s collection of James Bond books. Did you read the Bond books as a kid, or did you connect with the films first?

MICHAEL GILLETTE:

My dad had the books, Pan paperbacks from the sixties – great covers. They were stashed away in my bedroom in a little attic space. I read them when I was probably 12, 13… but the films… apart from occasional Bank Holidays, I don’t really remember them being on much. Do you?

JUSTIN LEWIS:

I don’t think they were on TV much before the eighties.

[Note: The first Bond film to be shown on British TV was Dr No, on ITV, on Tuesday 28 October 1975. In January 1980, the UK TV premiere of Live and Let Die attracted 23 million viewers on ITV, still unbeaten for a single showing of a film on British TV.]

JUSTIN LEWIS:

The main thing I remember with Bond was going with my dad and my brother to see a double bill at the Swansea Odeon on the Kingsway [don’t look for it, it’s not there anymore], this would have been Summer ’78. It was Live and Let Die and The Man With the Golden Gun, a double-bill. Two hours long, each of them, that’s a long afternoon. Especially when you’re eight years old. It’s actually a long time since I’ve seen a new Bond film. But I was also wondering to what extent the music of Bond films inspired those designs of yours. Were you thinking a lot about John Barry scores?

MICHAEL GILLETTE:

I do absolutely adore his music, yeah. Because I’m involved in the Bondiverse, I understand people are as passionate for 007 as we are for bands. I understand the draw of Bond. My job as a designer is to translate visually as a composer would do musically. The most enduring Bond thing for me is Barry’s scores, so sophisticated and timeless.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

They really hold up, as do the themes which generally hold up better than the films. Not many duds, surprisingly.

MICHAEL GILLETTE:

With John Barry, it’s the whole score… Things like Petulia from 1967, that’s a great soundtrack, or The Knack, and The Ipcress File. I listen to those more. I’m not an obsessive in the Bond world. And that possibly helps because you can get lost in detail. It helps to take a wider view.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

I was just thinking: have you ever tried to pastiche the Beatles’ album sleeves?

MICHAEL GILLETTE:

The only thing I remember doing, and it’s in Drawn in Stereo, is Oasis as the Yellow Submarine characters for Q.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

Of course, that’s right.

MICHAEL GILLETTE:

But otherwise, for years, I felt like I didn’t have enough skills to represent what they meant to me.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

You were too close to it!

MICHAEL GILLETTE:

But record sleeves remain the same and book covers keep changing. It’s interesting why that is.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

Why does that happen, I wonder? Even modern books do that – often the paperback edition six months later looks nothing like the hardback.

MICHAEL GILLETTE:

Music and visual culture are so locked together, I can’t disassociate them. I can’t imagine 2-Tone without that Walt Jabsco image. With a book, you don’t just stare at the cover for hours while you’re reading it. But a record… think of that bus journey between HMV in Swansea and home, where all you’ve got to look at is the sleeve.

Doing the Bond covers both times… immediately the reaction from some fans was that I’d performed an act of heresy. Changing record sleeves would cause a riot, unless you are Taylor Swift, but like many things about her, she defies logic and gravity.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

What’s your working routine like now? Do you sit at the desk every day, working on something, even if you’re just sketching?

MICHAEL GILLETTE:

Things have changed since COVID. My career has been mostly that of a rodeo illustrator: showing up every day, seven days a week, moving between clients, which went on for a quarter of a century plus. I don’t quite do that anymore. Now, I teach and do more selective commissions, because the world’s changed and I’ve changed. You know what it’s like with deadlines, right? For four years I worked for the New Yorker pretty regularly. I’d be about to clock off on Friday afternoon, and they’d e-mail and that’s the weekend done. For many years of my life, I leant in very hard.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

Are there things that surprise you about the young generation of new artists – in a good way, I mean?

MICHAEL GILLETTE:

I feel that we are fed a story that this generation is ‘hopeless and weak’. It’s been the same call since biblical times. By the end of teaching a class, or seeing my kids create, I have hope for us as a species. I believe in magic. I believe there’s an indomitable spirit of creativity that everyone’s got. We’re born with it, and we’re here to represent it the best way we can. I think that’s why people get unhappy when they don’t have outlets for their creative energy.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

It worries me in this country that young people are now supposed to only foster the talents that are going to get them a job or are going to get them a way of making money for other people rather than what they might actually be good at. And that’s really kicked in, in recent years. Obviously, education and passing exams is important, but what about the imagination?

MICHAEL GILLETTE:

Well, when you saddle people with debt in college, that puts an entirely different slant on it. The two grand from Saint Etienne paid off my student debt. I worked all the way through college to keep it low, but that’s the difference – I could afford a London life, albeit a tight one. Two thousand pounds at a time when my rent in Islington was £55 a week. That kind of maths wouldn’t work now with London housing. The pay for a similar gig in 2025 would be more or less the same, and cover about five weeks’ rent.

I’ve had a career, but it wasn’t encouraged, it was unlikely even then. Most folks who studied illustration didn’t become illustrators. Not saying that being an illustrator is the high bar of anything. We’ve saddled students with middle-aged debt and the anxieties that go with it. It’s unfair. As a teacher, I try to help as much as I can. My teachers were often art school bullies who’d give you a good kicking. Maybe that was the point; maybe if you survived that, you were strong enough for the outside world! But I try to do the opposite, I hope to encourage.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

What sort of age are your students?

MICHAEL GILLETTE:

19, 20, 21. They’re super-young, but the same impulses are inherent. There’s that beauty of openness and that’s why avoid telling them ‘it’s like this’ and ‘you have to do that’. You make it up [for yourself]. I made it up by knocking on Saint Etienne’s door.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

You find a way.

MICHAEL GILLETTE:

You find a way, be creative. Where one person will walk into a room and see nothing but walls, another will find an open door. That’s why I believe in magic – it’s very mysterious how it all works. We’ve known that from all the music stuff we’ve read, the connections and the odd chances of luck.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

Nobody really knows where ideas come from.

MICHAEL GILLETTE:

Hundred per cent, yeah. Writer’s block, artist’s block… who’s doing the blocking? It’s not the universe, it’s the writer and the artist. You can shut it down really easily. [With creativity] it was never encouraged, but now it’s probably worse, it’s harder to freelance. But where there’s a will… I needed a period of time to be able to make mistakes, be slack, be lost and not worry about finances. Talent will out, but it needs support.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

Yes, particularly the process of trying out things and making mistakes. Unless you have particularly wealthy parents now, it’s difficult to do that. And especially when you’re young, you have the energy – you can stay up till three in the morning doing creative things.

MICHAEL GILLETTE:

You get an era where you can batter yourself almost to death and continue working and somewhat thriving. I’ve lived in two of the most expensive cities in the world – London and San Francisco – and managed to survive making artwork. It’s a bloody miracle. For younger people, maybe they’ll think in a different way, and it’s not about London or San Francisco, because those are overrun with investment bankers and tech workers… St Louis, where I’m living now, is different, it’s a post-industrial city, there are opportunities to live creatively.

In London, the generation before us had studios in Covent Garden. Our generation… my studio was in Hoxton Square. Now… Pushing out people who are regular human beings, let alone artists from a metropolis like London – that’s tragic. It’s everyone’s loss. But the fundamental soul of creativity that I see in young people is exactly the same. It’s like a timeless river. That spirit always makes me feel hopeful.

————-

All images in this piece (apart from my usual FLA header and cassette inlay) are (c) Michael Gillette. Thanks so much to him for allowing FLA to include them.

Much more on Michael Gillette at his website: https://michaelgilletteart.com

You can order the book directly from his website, here: https://michaelgilletteart.com/products/drawn-in-stereo-book

You can also order art prints for Michael’s James Bond book cover designs (pictured here): https://michaelgilletteart.com/collections/prints

You can follow Michael on Instagram at https://www.instagram.com/michaelgilletteart/

——

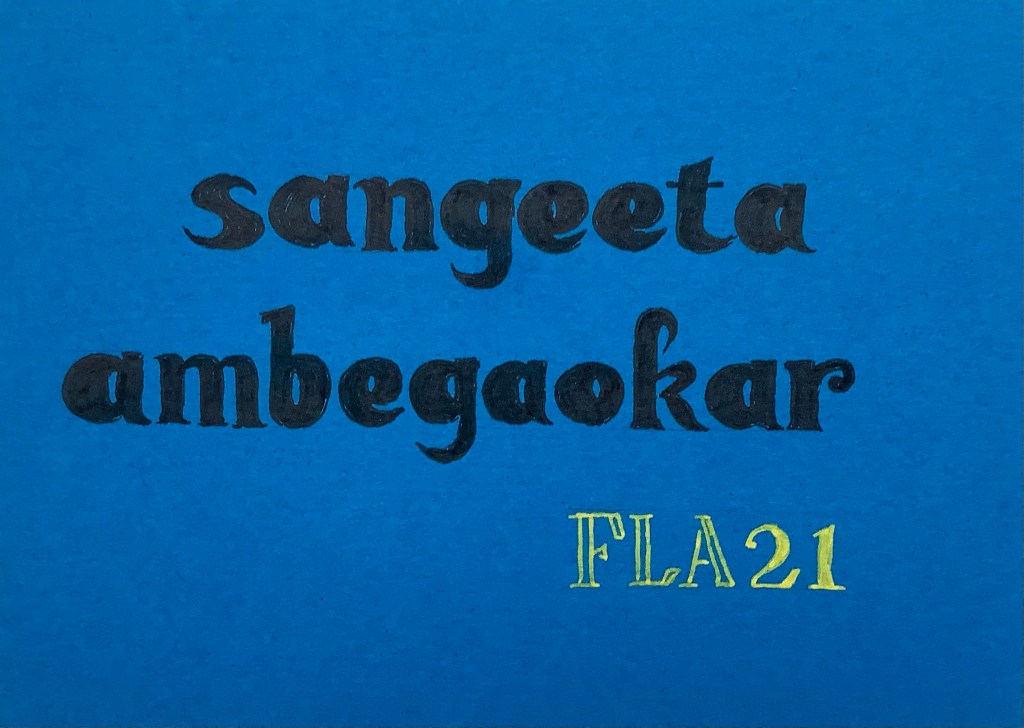

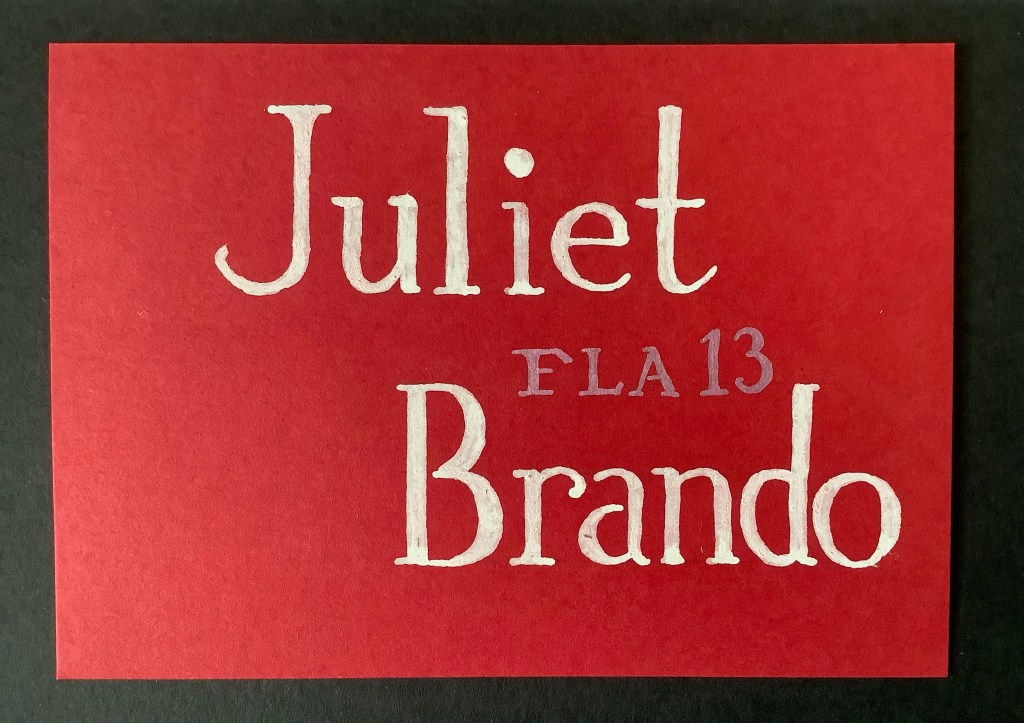

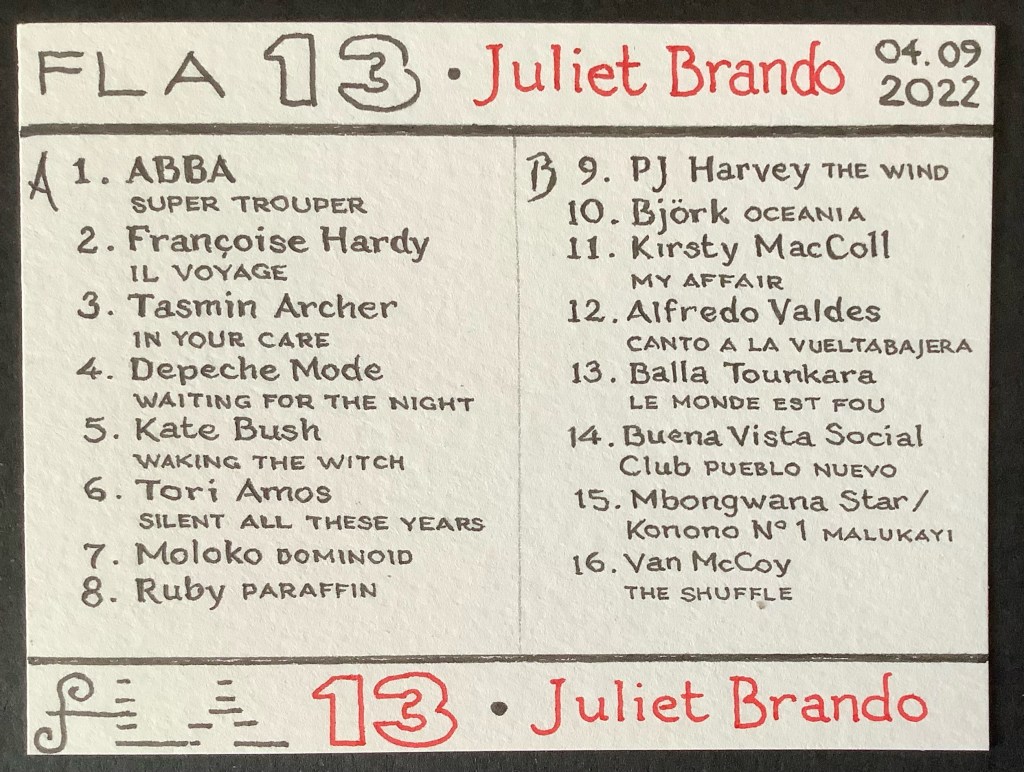

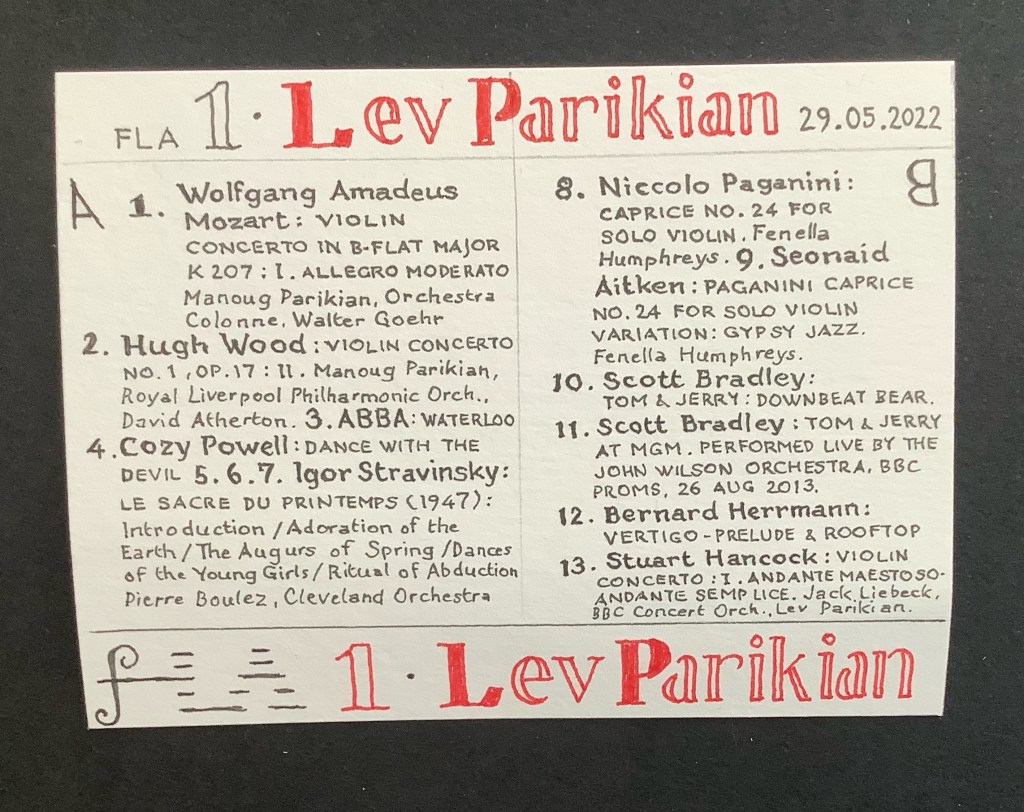

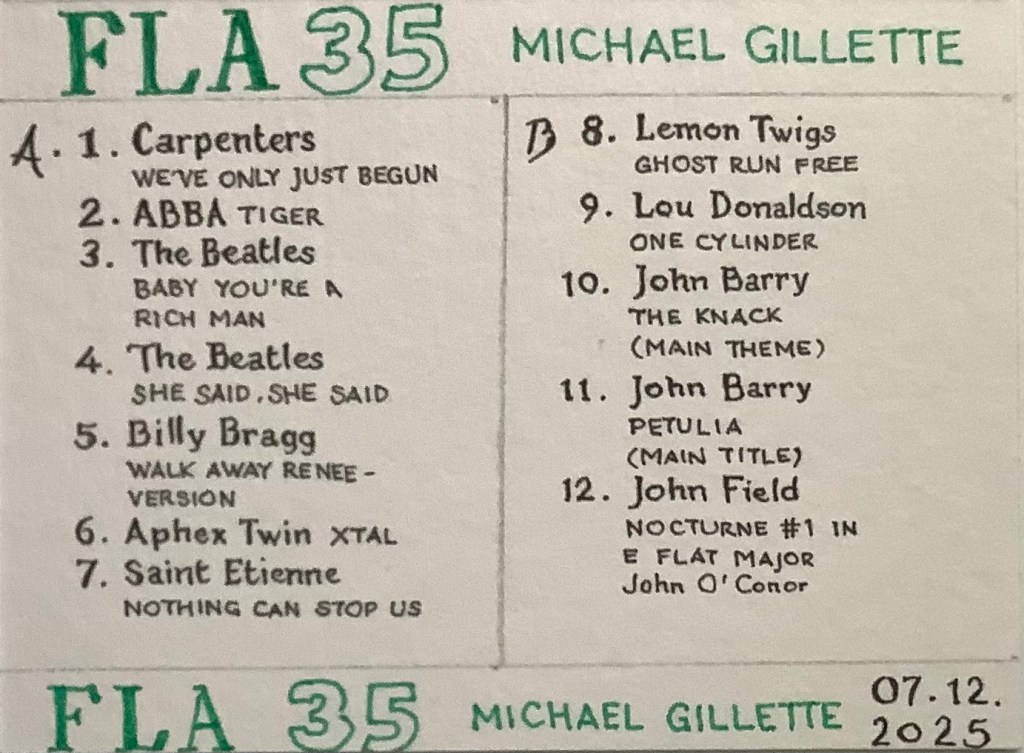

FLA Playlist 35

Michael Gillette

(For the time being, this site and project uses Spotify for the conversation playlists, but obviously I disapprove that Spotify doesn’t pay artists and composers properly, and other streaming platforms are available, as are sites to buy downloads and buy recordings. For consistency, you can also listen to the selections via YouTube (where available), and links are provided in each case, below.)

Thanks to Tune My Music, you can also transfer this playlist to the platform or site of your choice by using this link: https://www.tunemymusic.com/share/5yuhEgpQ6o

Track 1:

CARPENTERS: ‘We’ve Only Just Begun’:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xeBoRF5tgDo&list=RDxeBoRF5tgDo&start_radio=1

Track 2:

ABBA: ‘Tiger’:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=htziQt0pCAQ&list=RDhtziQt0pCAQ&start_radio=1

Track 3:

THE BEATLES: ‘Baby You’re a Rich Man’:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=i5m-sgtwFck&list=RDi5m-sgtwFck&start_radio=1

Track 4:

THE BEATLES: ‘She Said, She Said’:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NZOBWYHgZjw&list=RDNZOBWYHgZjw&start_radio=1

Track 5:

BILLY BRAGG: ‘Walk Away Renee (Version)’:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=iHrFkSeLukA&list=RDiHrFkSeLukA&start_radio=1

Track 6:

APHEX TWIN: ‘Xtal’:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2tOutF8B3f8&list=RD2tOutF8B3f8&start_radio=1

Track 7:

SAINT ETIENNE: ‘Nothing Can Stop Us’:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RAZUwvYqhpg&list=RDRAZUwvYqhpg&start_radio=1

Track 8:

LEMON TWIGS: ‘Ghost Run Free’:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ewKdcUl3J7c&list=RDewKdcUl3J7c&start_radio=1

Track 9:

LOU DONALDSON: ‘One Cylinder’:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=F8RCGr8FEt0&list=RDF8RCGr8FEt0&start_radio=1

Track 10:

JOHN BARRY: ‘The Knack (Main Theme)’:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=k3utY_mJjK8&list=RDk3utY_mJjK8&start_radio=1

Track 11:

JOHN BARRY: ‘Petulia (Main Title)’:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qhKQ1UT-MjE&list=RDqhKQ1UT-MjE&start_radio=1

Track 12:

JOHN FIELD: ‘Nocturne #1 in E Flat Major’

John O’Conor:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2YJXgmLXTew&list=RD2YJXgmLXTew&start_radio=1