The Emmy-award winning David Quantick began writing for a living in the early 1980s, shortly after studying law at the University of London, and has barely stopped since. For thirteen years, he was at the New Musical Express, where he originated a torrent of reviews, articles and thinkpieces. There, his association with the late Steven Wells on such anarchic, hilarious columns as ‘Ride the Lizard!’ led to feedback from a young BBC radio producer called Armando Iannucci. Over thirty years after the astonishing On the Hour for Radio 4, David has continued to be a part of Armando’s writing team on such internationally acclaimed television projects as The Thick of It, Veep and most recently Avenue 5.

Frankly, David has written so much, there isn’t room to list it all: sketches for Spitting Image and The Fast Show, the first-ever internet sitcom (2000’s The Junkies, written with Jane Bussmann), Chris Morris’s Brass Eye and Blue Jam, and ten years of Harry Hill’s TV Burp, amongst many, many other things.

In recent years, David has turned to novel writing – his seventh novel, Ricky’s Hand, is out now – as well as writing the screenplay for the 2021 romcom feature film Book of Love, starring Sam Claflin and Verónica Echequi.

I have been a fan of David’s work since the 80s, and have since got to know him a little bit too, so was delighted when he agreed to join me on First Last Anything to discuss his love of music. And so, one morning in May 2022, he told me about his formative years in Plymouth and Exmouth, the appeal of K-pop, and how to review a new pop record. We hope you enjoy it.

—

DAVID QUANTICK

In the 60s, at first we didn’t have a record player, and then at some point, we got a Dansette from our neighbours Pam and Tony. For me, it was quite an influential thing because the records that came with it were some novelty singles: ‘Itsy Bitsy Teeny Weeny Yellow Polka Dot Bikini’, ‘Seven Little Girls Kissing and Hugging with Fred’, and there were some Val Doonican albums with novelty songs on like ‘Slattery’s Mounted Foot’ and ‘Paddy McGinty’s Goat’. But there were also two Goon Show albums, Best of the Goons, volumes one and two, my first exposure to recorded music.

Meanwhile, my dad used to love opera. We didn’t have any in the house, but he used to go a lot to the opera, and used to say it was rubbish if it was in English. If you could understand the words, it was no good. And he also used to go to musicals. He worked in London just after World War II, so he saw an amazing amount of original British productions of things like South Pacific and Oklahoma!

But what really takes me right back to my childhood is Nat King Cole. We had an album called The Nat King Cole Story, and it had links narrated by, I think, Brian Matthew. I still love Nat King Cole’s voice.

Later on, my parents were in the Readers Digest book and record club, so we had lots of Readers Digest box sets – country music, pop music, bit of classical. They liked Howard Keel, the light opera singer – and they liked The Carpenters, although my parents hated the fuzz guitar solo on ‘Goodbye to Love’ – I think they just thought it was a bit much.

JUSTIN LEWIS

That solo’s like something invading from a different world.

DAVID QUANTICK

It does work for me, but it is a bit like having Jimi Hendrix on the Nat King Cole record.

JUSTIN LEWIS

‘Yesterday Once More’ by The Carpenters is, I think, the first pop song I remember being a current, new record. Round about 1973. It’s weird to have, as one’s first-hand memory of pop music, a song that’s about nostalgia.

DAVID QUANTICK

The first like that I remember is ‘Hello Dolly!’ by Louis Armstrong, followed by ‘A Hard Day’s Night’, and that would have been on the BBC Light Programme. I would have been very little. 1964. Yeah, and I also remember my first TV musical memory – because we never watched Top of the Pops – was seeing John and Yoko getting off an aeroplane on the news [1969], wearing white suits like characters in The Champions.

JUSTIN LEWIS

What do you remember about school music lessons?

DAVID QUANTICK

There was ‘banging things at primary school’. The BBC used to do these schools radio programmes called Time and Tune – there’d be an accompanying magazine and you’d play along with xylophones. The one I remember was basically making space sounds.

JUSTIN LEWIS

Time and Tune ran for years. We had that at infants school. A different story project every term. This sounds like it might have been ‘Journey into Space’ (first broadcast, spring 1965, repeated spring 1968).

DAVID QUANTICK

For years, with the Carpenters, I was convinced that the song we practised in the Time and Tune lessons was ‘Calling Occupants of Interplanetary Craft’ (1977), but obviously, as I would realise later on in life, that would have been impossible.

JUSTIN LEWIS

And did you learn any musical instruments?

DAVID QUANTICK

When I was briefly at public school, I had piano lessons and the teacher asked if I was left-handed. I had oboe lessons and I got the cleaning feather stuck in that thing. I bought an acoustic guitar from the Burlington catalogue, the less famous version of the Freemans catalogue. And I think it was the obligatory Kay acoustic, because Kay made all the guitars that poor people had, and I couldn’t tune it. So I gave that up. That was my musical education as a child.

—-

FIRST: WINGS: ‘Mull of Kintyre’ (1977, single, Parlophone)

JUSTIN LEWIS

So, the first single you ever bought. I think at the time the best-selling single there had ever been in Britain. Two million sales.

DAVID QUANTICK

Yeah, it outsold ‘She Loves You’ which made Macca very happy and Lennon less so. There was a great lie that I told for many years. When people asked me my first single, I used to tell them it was ‘Airport’ by the Motors, which was the second single I bought.

I had a school friend called Ewan, and whenever I talk about The Beatles, he still likes to say how embarrassing it was that I was a Beatles fan at school in the sixth form. This was just after punk, it was 1978, the Sid Vicious era of the Sex Pistols, Sham 69… Now, we have this world of Beatles obsession and Beatles podcasts and remixes and all that. But back then… it wasn’t that the Beatles were loathed, but they were considered ‘boring’. They were summed up by ‘the Red and the Blue albums’, no-one had any of the other albums, and ELO had come along and stolen their crown and shat on it… Liking the Beatles, as I did, was just so naff. Ralph Wiggum would have liked The Beatles in 1978. And owning ‘Mull of Kintyre’ was even worse, I think.

JUSTIN LEWIS

When I was first obsessed with pop music in the early 80s, Lennon had just died, so there was still a lot of ‘John’s the best Beatle’, but my other big obsession was TV comedy, and it soon became clear that Paul McCartney had become the whipping boy in comedy for everything that was square in pop music. I think that only really started to move on when he collaborated with Elvis Costello at the end of the decade [on Costello’s Spike and McCartney’s Flowers in the Dirt]. Costello did this interview where he just went, ‘Why’s everyone so rude about McCartney? He’s written more great songs than almost anyone else.’ I’m paraphrasing, but that kind of thing.

DAVID QUANTICK

Flowers in the Dirt was interesting, not just for having Costello, but it marked the beginning of McCartney just going, Fuck it, I’m not gonna do records that sound like everybody else. Then there’s the production shift. Every so often now, he’ll do a record with Nigel Godrich or Mark Ronson, but he’s basically saying, ‘I’ll just do what I want.’

JUSTIN LEWIS

I wondered if Anthology (1995–96) was what really cemented The Beatles, because they’ve never really gone away since then. In the 70s, when I was a child, I don’t really remember hearing The Beatles on the radio. They might well have been played, but I just don’t remember it.

DAVID QUANTICK

It’s like if you went to a disco, as they were called then, a student disco, or a 60s night, you’d never hear The Beatles, even though some of their records are real stompers, like ‘Got to Get You Into My Life’ or ‘Get Back’… But you couldn’t play a Beatles record because it stands out too much, it’s like entering a lion in a cat show. It just doesn’t work in that context, even though in a real sixties disco, you would have followed the Kinks’ ‘You Really Got Me’ with ‘Day Tripper’ or whatever. I would love to see, actually, a transcript of a real 1966 DJ’s setlist. If there ever was such a thing.

JUSTIN LEWIS

And you rarely, if ever, get the Beatles on multi-artist compilation albums.

DAVID QUANTICK

No, absolutely, and that’s why [Starsound’s] ‘Stars on 45’ (1981) was such a hit because you could go to a disco and dance to The Beatles. I mean, the legals were probably quite powerful on Beatles stuff on compilations. Like it’s weird when you watch a film and there’s a Beatles song in it. ‘How the hell did they clear that?’

JUSTIN LEWIS

Just going back to ‘Mull of Kintyre’. You’d have been sixteen when it came out, and that does seem – if you don’t mind my saying, given what a massive fan of pop music you are – quite a late start for a first single. I mean, presumably, you were borrowing stuff from friends, or taping stuff off the radio – was there a record library?

DAVID QUANTICK

No, I didn’t have any of that. I liked comedy. As I say, it was rare for me to watch Top of the Pops, though I remember Alice Cooper’s ‘School’s Out’ because obviously I was at school. Queen’s ‘Killer Queen’ seemed a bit like a Gilbert and Sullivan or a Noël Coward song. But I would enjoy the Wurzels, the comedy records. I didn’t get rock. I literally didn’t. I preferred classical music. And I had some albums: Dark Side of the Moon which sounded amazing, and I had a Mike Oldfield box set which I loved…

I had changed schools a couple of times, felt a bit isolated, didn’t have a lot of friends, stayed in a lot. But then in the sixth form a couple of other kids came from different schools, and I became friends with them. They were popular kids and they liked punk and they liked John Peel. So I kind of skipped the entire history of rock music. I was hearing The Clash for the first time at the same time as I was hearing Motown for the first time.

JUSTIN LEWIS

So when people talk about punk as ‘year zero’, you actually experienced it like that, because in a sense, you had no reference points. Or if you did, they were all from different areas of culture.

DAVID QUANTICK

Yeah. It was easy to get into punk and I started to understand riffs and why ‘dang-dang-dang’ was good, but I also like categories, and it was easy to spot what was punk. Olivia Newton-John wasn’t punk. The Dickies were. You felt a bit cool because you didn’t like disco – though obviously now I love disco. These were my new friends, and I liked what they my new friends liked.

And you could go to Lawes Radio which was a local music shop in Exmouth, selling radios and electronic equipment, but they subscribed to the indie chart so they would have Crass singles in the window display. And they were really nice people, but they knew they couldn’t compete with [WH]Smiths. They had a ‘30p Box’ that seemed to be crammed with early XTC singles.

JUSTIN LEWIS

One of the aims of this series is to emphasise how record collections, especially early on, are almost accidents, because they’re based on how much money you have at that moment. What have the shops even got in stock? You might go to the shop expecting to buy Record X and they haven’t got it, but they have got record Y which is a bit cheaper. And also they’ve got that thing in the 10p bin which looks interesting. You’re buying a lot of things on a whim, you’re not curating it – that terrible word.

DAVID QUANTICK

It’s probably a bit more random. I would buy things that I’d heard, and I’d be embarrassed later. I had a single by a band called The Autographs called ‘While I’m Still Young’ (1978), which is great. It was a Mickie Most-concocted punk band, and it came on – I think – yellow vinyl.

JUSTIN LEWIS

I’m not familiar with this one! The mention of Mickie Most suggests it was on RAK Records.

DAVID QUANTICK

I think it was RAK, yeah. 30p. And I’d heard it on Roundtable, on Radio 1, and I loved it because I didn’t know any better. Of course I got rid of it when I realised… no-one ever told me to get rid of it, but I did. Now I look it up online and it’s not revered but it’s well-respected glam punk… It’s great. ‘While I’m Still Young’ – sung by some men who weren’t still young.

JUSTIN LEWIS

Knowing you a little bit, and hearing you on various podcasts and interviews talking about your early forays into writing, it occurs to me that you got into music journalism in the 80s, not directly because of music, but because it provided you with an outlet to write what you wanted. Because a lot of your background was liking comedy and novelists. And when you went to, particularly, the NME, in those days, you could write about authors, or cult films, or anything really. Didn’t you review the singles in the NME once as a Flann O’Brien parody?

DAVID QUANTICK

No, I wrote the gossip column as The Brother from Cruiskeen Lawn. It’s easy to parody. It’s basically: ‘This morning such and such happened’ and the other bloke who’s Flann O’Brien is going, ‘Is that a fact?’ So it’s a really good structure. I think we got one letter accusing the anonymous gossip column writer of racism. Because of course, there was no context, I didn’t explain this.

But it was great because you had to fill a weekly paper, all this space. The Thrills! section was meant to be interviews with up-and-coming bands, but there weren’t enough of those, so me and Stuart Maconie and Andrew Collins would fill it with comedy.

JUSTIN LEWIS

Somebody circulated on Twitter recently that Rock Family Trees parody the three of you worked on. An epic, incredible piece of work.

DAVID QUANTICK

They let us do anything then. And Stuart and Andrew were seconds away from being on Naked City on Channel 4 as columnists [co-hosted by the teenage Caitlin Moran], and I was a writer on that. But I hadn’t really fitted in at the NME in the 1980s, I hadn’t really liked the music. Then there was a sort of golden age when Alan Lewis and Danny Kelly were editing it [1987–92] – and I became friends with Andrew and Stuart. It was this wonderful thing when the NME was funny. You could write parodies, fake interviews. Working with Steven Wells [aka Swells] as well – we had two pages a week to write anything, which ended up with us working for Armando Iannucci.

JUSTIN LEWIS

Yes, apparently the piece he spotted was about classical music and how all stringed instruments are different-sized guitars. Like the cello is in fact a massive guitar.

DAVID QUANTICK

I’m always convinced that got us the job writing for On the Hour. Maybe because Armando didn’t like rock! Just to trot out my favourite cliché: the NME was ‘Cambridge for losers’. There’s a reason why me and Steven were one of the few writing teams in comedy who didn’t have an Oxbridge or public school education. And that’s because of Armando, you know – the back door route.

—

JUSTIN LEWIS

I saw you write the phrase ‘Nostalgia isn’t reviewing’ recently. As a reviewer, do you think your first impression of a record should be the one you stick with, regardless of whether you change your mind later?

DAVID QUANTICK

In real life, if you buy a record, and you play it, you love it because it’s by your favourite band, but you don’t really like it yet, because it’s a load of new music to take in. But you keep playing it, and generally the more you play it, the more you love it. You might even go back and play a record you hated but, because you’ve heard it every day, you love it.

But in terms of writing a review for a new record, you’ve only got your first impression. Your job is to try and imagine what you will think of it in the future, having heard it once. You’re livetweeting, to use a modern phrase, playing a record for the first time. What it sounds like compared to other things. Where does it fit in? And if you revisit an old review from a weekly music paper, there should be references in it that you won’t understand now. Like HERE COME THE HORSES or something. Because there should be references to where it fits that week ‘in June 89’. What I loathe, by the way, about Wikipedia, is they say things about old records like ‘allmusic.com gave it three stars’. Who cares? I want to know what Melody Maker said at the time.

JUSTIN LEWIS

When I was about 18, in the late 80s, I probably spent more on music magazines than on records. Lots of the reviews was stuff you wouldn’t hear about, unless you happened to hear Radio 1 at the right moment, so you had to rely on a critic to convey what it might be like. That review had to work on the page as a piece of writing.

DAVID QUANTICK

I would have little rules when reviewing. I would always try and describe the music, but also name some of the songs, and maybe some lyrics, to give people something to hold on to. And I’d make comparisons, so say, the Wonder Stuff’s ‘Size of a Cow’: ‘It sounds like crusties doing Madness.’

JUSTIN LEWIS

Which were useful, especially with records that Radio 1 might not play.

DAVID QUANTICK

With most of the NME bands, you could hear it on John Peel or the Evening Session. But when I started at the NME [1983], I got to interview the bands who nobody else wanted. Eddie and Sunshine, for instance, who were great. Or a bloke who’d been in Pilot. Records nobody else wanted to review. These were records you wouldn’t hear on John Peel. I reviewed Nikki Sudden records, because I’d liked Swell Maps, and they’re now re-evaluated as classic indie, but he wouldn’t get an interview in the NME because he was ‘five years ago’ and John Peel wouldn’t play it. Because he was like pre-Primal Scream. He was trying to make 60s rock music in an indie studio.

JUSTIN LEWIS

For me, as a young person, there was also Saturday morning TV, or stuff in the afternoons. Which you don’t get anymore. And you could get quite unlikely bands in there because the music bookers have to fill the space, and so you could get quite leftfield music on kids’ TV. I once saw Pere Ubu acting as the musical interlude on Roland Rat – The Series [BBC1, 25/07/1988].

DAVID QUANTICK

I remember seeing Buzzcocks on a Saturday morning show, doing ‘Are Everything’.

JUSTIN LEWIS

I think that might have been Fun Factory [Granada, 1980].

DAVID QUANTICK

I also remember going with my friends Miaow, Cath Carroll’s band, to Alton Towers where I think they were filming Hold Tight! [ITV’s quiz and music show for children filmed at a theme park. This was the last episode, TX 23/09/1987.] It was a really weird day because I met Graham Stark from Peter Sellers’ stuff, who was sitting in a car (‘Are you Graham Stark?’ ‘Yes I am’) and Miaow were on, and Thomas Lear was on who’d been on Mute Records in the early 80s. It was more NME than the NME.

—-

LAST: PSY: ‘Gangnam Style’ (2012, single, YG)

JUSTIN LEWIS

I don’t notice lots of people my age championing K-pop, but you very much do.

DAVID QUANTICK

Like millions of people who aren’t sixteen, the obvious entry point with K-pop for me, about ten years ago, was ‘Gangnam Style’ by PSY. I love a novelty record, which stands out and isn’t like anything else. And then I discovered that I really liked K-pop, because bands like Girls’ Generation of Wonder Girls had taken the Girls Aloud template: largely five-piece female bands with really good dancefloor singles, and really great choruses.

Then I was writing a book set in the world of K-pop, which gave me excuses to immerse myself in Korean culture: movies, books, history, North and South. I also became obsessed with North Korean music – which is something we won’t go into now, but one of my proud moments was watching that Michael Palin series about North Korea. He was in a cafeteria there, and I recognised the song that was on in the background. It was ‘Let’s Work’ by the Moranbong Band. That made my day.

Then my wife Jenna really got into K-pop, we watch K-dramas together, and she’s a massive BTS fan, an expert in fact. I’m less a fan of BTS as a group, but their solo stuff… they were a rap crew but in various rap teams and their solo mixtapes are astonishing. They’re downloadable for free. If you just put ‘BTS solo mixtapes’ in Google, you can get the one by Agust D which is actually Suga from BTS. There’s a brilliant song called ‘Daechwita’ which I can’t pronounce.

This is quite common now, but about four years ago, I went into HMV in Maidstone, and I was shocked to see a separate K-pop section in there. All these big boxes, costing £30, containing a CD, often just an EP and photos and notebooks and stuff. My wife tells me that BTS get in trouble with the charts for that because including promotional material makes your album non-eligible for chart status. The sales of CDs are not counted. Also, BTS have released their new hits compilation with four unreleased demos on CD, which is doing the fans’ nuts in because they haven’t got CD players – because they’re kids.

But because of these K-pop boxes, they don’t integrate into the rest of the shop, and it makes K-pop look separate in the way that The Beatles were.

JUSTIN LEWIS

What’s your perception of how British media treats K-pop?

DAVID QUANTICK

I’ve seen two approaches. The NME one, which is the current way of treating everything in the same breathless news way. And there’s the way the posh broadsheets treat it, which is like the sniffy way they used to treat pop. I’ve seen reviews of BLACKPINK and I start screaming at the computer. They don’t mention that none of the tracks from the last EP are on the album. They don’t mention the multiracial mixed line-up of the band. All they do is write, ‘I don’t really like this kind of music, but it reminds me a bit of something I do remember from the 90s’. It’s like reviewing The Osmonds. The sneer is back.

But what really gets on my nerves is that television still makes these documentaries where a light entertainment presenter goes to Seoul and has some weird food and says a few words of Korean and then goes to a karaoke bar… It just drives me absolutely spare. We’re still doing the funny foreigner approach?!

I like K-pop, not just for me to keep up with new music, but also because I find, due to my age and the circles I move in, that you’re always being dragged down by the hands of the dead. It’s so much easier for me to fill my iTunes with old stuff. I just bought a Bryan Ferry live album in 2020 in which he perfectly recreates some songs from fifty years ago. I just bought some Luxuria because I hadn’t heard much Howard Devoto stuff. I’m constantly buying old music that’s nice to have on the computer, but really I would like the percentage to be reversed: to buy 5 per cent old music, and 95 per cent new music.

But when you listen to the average pop single now, if you take off the vocals, it sounds like something John Peel would have played in 1983. Cutting things up, raps, post-post-post-sampling, post-post-Pop Will Eat Itself. Pop music now is NUTS. What I’ve been recently doing is driving around with Radio 1 on, and the records stop sounding the same when you hear them all together in a bunch.

JUSTIN LEWIS

Radio 1’s great at the moment, I think.

DAVID QUANTICK

The DJs are generally quite funny and, at worst, unobtrusive. An afternoon with Radio 1 is quite interesting these days. Yeah, there’s a lot of generic stuff, but even so.

JUSTIN LEWIS

My two favourite radio stations now are Radio 1 and Radio 3 and although they’re entirely different in presentation, I like that both stations are playing about 80 per cent stuff I don’t already know. Radio 2 drives me up the wall a bit. They have a habit of turning records you used to love into wallpaper.

DAVID QUANTICK

If you turned on Radio 2, now, any time, what’s playing? What’s the record? I’ll tell you mine.

JUSTIN LEWIS

It feels like it should be ‘We Built This City’.

DAVID QUANTICK

See for me, it’s ‘You Keep It All In’ by The Beautiful South. I’ve got no evidence for this.

JUSTIN LEWIS

In the early 90s, when Radio 2 was still quite MOR, it felt like any time it came out of a news bulletin, they’d start the next hour with ‘Going Loco Down in Acapulco’ by the Four Tops. [Laughter]

—

ANYTHING: PADDY MCALOON: ‘I’m 49’ (2003, from I Trawl the Megahertz, Liberty Records, reissued under Prefab Sprout name, 2019, Sony Music)

JUSTIN LEWIS

Was this Paddy McAloon solo record a big surprise to you, given how different it was from usual Prefab Sprout records?

DAVID QUANTICK

It wasn’t a big surprise because I’d got used to the idea of artists doing something completely different and there were loads of reasons for Paddy doing it, to do with his health.

JUSTIN LEWIS

Now reissued under the Prefab Sprout name.

DAVID QUANTICK

That repetition of ‘I’m 49, divorced’. The way Paddy had slowed the voice down to make it sound more melancholic. It was like a Gavin Bryars record.

JUSTIN LEWIS

It really is reminiscent of ‘Jesus’ Blood Never Failed Me’.

DAVID QUANTICK

With Prefab Sprout, I hadn’t really been a fan. I liked some odd songs by them, ‘Cruel’, stuff on Swoon, the first album. But it sounded a bit old school – corporate and irritating at the same time. Like I loathe Steely Dan and that kind of jazzy pop. But then I heard ‘I’m 49’ and it was brilliant. Makes me like Prefab Sprout a bit more.

JUSTIN LEWIS

At one point on ‘I’m 49’, in this mass of sampled voices from radio phone-ins, there’s a sample of someone going ‘What’s wrong?’ Which I thought sounded not unlike your voice, strangely enough. Turns out it was apparently Jimmy Young [then of Radio 2, doing the Jeremy Vine phone-in slot]. And it also makes me think of Chris Morris’s Blue Jam series on Radio 1, which of course you wrote on, and I don’t know if Paddy had heard that. That mixture of comforting music and disturbing voices.

DAVID QUANTICK

It reminds me of Different Trains by Steve Reich as well. The voices cutting in like a countermelody. But with I Trawl the Megahertz as a whole, I’m a bit like the person who went to see David Bowie in 1970, just so they could hear ‘Space Oddity’. I play ‘I’m 49’, but I don’t really play the rest of the record.

It’s so out of character, for Paddy McAloon to do something that’s not song based, because he’s such a song obsessive. It’s obviously to do with the way he felt at that point. Middle-aged pop stars either ignoring it like Mick Jagger, or to start eating yourself like Bowie referencing himself on The Buddha of Suburbia. Or McCartney making Britpop with the Flaming Pie album. But what Paddy McAloon does here is express the way I felt about being middle-aged. Ironically now, because that was 20 years ago. But now it’s a really brilliant, really effective piece of music. The whole record, you only need that slowed down sample of a man saying, ‘I’m 49, divorced.’

—

JUSTIN LEWIS

There’s a new film you’ve written, Book of Love, and the composers have actually soundtracked your film with original songs. They didn’t just choose stuff from a back catalogue of hits. What was it like having your screenplay as a sort of jumping off point for their work?

DAVID QUANTICK

It was really nice to have a soundtrack. I had no consultation at all with the composers, because once they started making this film which was in Mexico and I couldn’t go, I was kind of outside the process. When I was writing the screenplay, I had different music in mind, a lot of reggaeton. But I love the soundtrack we’ve got. It’s an odd mix, but it works quite well because you know, it’s British and Mexican, and romantic and comedy as well. Romcoms are weird because you know it’s a comedy but it’s also a ‘rom’ so you have to have romantic scenes.

I do sometimes listen to music when I’m writing. With my novel, All My Colors, which was meant to be a Stephen King pastiche set in the 80s, I just listened to the Stranger Things soundtrack and that just led me to John Carpenter. When I wrote another novel, Night Train, that was fun because I listened to train songs, and none of the songs have got anything to do with each other except that they’re all about trains and quite a lot of them go dig-dig-dig-dig-dig.

JUSTIN LEWIS

Obviously you’ve also been a song lyricist – Spitting Image as far back as the 80s, and more recently 15 Minute Musical (for Radio 4) and other things too. What’s your approach to writing musical lyrical parody?

DAVID QUANTICK

I don’t know what my approach is. Brevity. It’s restrictions, really. With 15 Minute Musical, there was one, which sounds insane now… about Julian Assange being in the Embassy and it was set to a pastiche of Joseph and the Amazing Technicolor Dreamcoat.

When I wrote lyrics for Spitting Image songs, I wrote a song parodying U2, ‘I Still Don’t Know What I’m On About’ [1987], Bono talking in meaningless phrases. I wrote that solely for the one line, ‘You can change the world, but you can’t change the world.’

And I’m really pleased I wrote a rejected Pet Shop Boys parody for Spitting Image. When I told Neil Tennant the lyric, he claimed to be entertained. ‘Let’s run away together if we’re willing/Those eclairs are never a shilling.’

JUSTIN LEWIS

Very good.

DAVID QUANTICK

As they’ve written at least two songs in which Neil Tennant tells somebody else that they should run away together.

JUSTIN LEWIS

‘Two Divided by Zero’ and…

DAVID QUANTICK

‘One More Chance’.

JUSTIN LEWIS

I’m presuming with the songs, like the sketches, you weren’t on the writing team, you just sent stuff in as a freelancer.

DAVID QUANTICK

Yeah, I remember being invited up to the studio by the producer, Geoffrey Perkins, who kindly paid the train fare, and I went to see the U2 item being filmed. So I met the Bono puppet – and I was quite impressed, because they’d only just made it. They hadn’t done many groups because once you’ve made an Edge puppet, what the fuck do you do with it?

And that connection with Geoffrey led me to a weird period when I was a music suggester for Saturday Live and Friday Night Live, the Ben Elton vehicles. Geoffrey and the other producer, Geoff Posner, said, ‘You’re a music journalist. We don’t really know what bands to get.’ It was great, because their idea of a new band was not mine, and not the NME’s, so I would suggest people like The Pogues and Simply Red. I think I got a credit and fifty quid, something like that.

JUSTIN LEWIS

You’ve got a family now, obviously. Do your kids introduce you to music you’ve not heard before yet?

DAVID QUANTICK

They like The Beatles and they’re starting to like BTS. They really like The Wombles. That’s probably me pushing a bit because I know Mike Batt and I wanted to show off that I know Mike Batt.

But one of the things I loved about writing on TV Burp was that Harry Hill had older children, and was pretty up on the pop scene, and he would drop a lot of references to contemporary hits into his work, and it was nice because it wasn’t just indie. Working in comedy in the 90s for me, because I was a music journalist, all the stand-ups would make me mixtapes. And it was horrible because they just made me NME-type tapes. Don’t ever talk to a stand-up about their music collection, because it’s all fucking Pavement.

——

David Quantick’s novel Ricky’s Hand was published in August 2022 by Titan Books.

Book of Love can currently be streamed at NOW TV Cinema and Amazon Prime. It triumphed at the Imaagen Awards 2022, winning Best Primetime Movie.

The second series of Avenue 5 began airing on Sky in the UK in autumn 2022.

David has now written three series of BBC Radio 4’s Whatever Happened to Baby Jane Austen? starring Dawn French and Jennifer Saunders. In both 2023 and 2024, it won the British Comedy Guide’s Award for Best Radio Sitcom.

In late 2024, he began co-hosting The Old Fools, a very funny podcast series with fellow comedy writer Ian Martin and special guests every week. You can listen to it at Apple here, or wherever you listen to podcasts: https://podcasts.apple.com/gb/podcast/the-old-fools/id1774465485

For tons more on David’s life, career and news, as well as regular new short stories, his website is at davidquantick.com

You can follow him on Bluesky at @quantick.bsky.social

—-

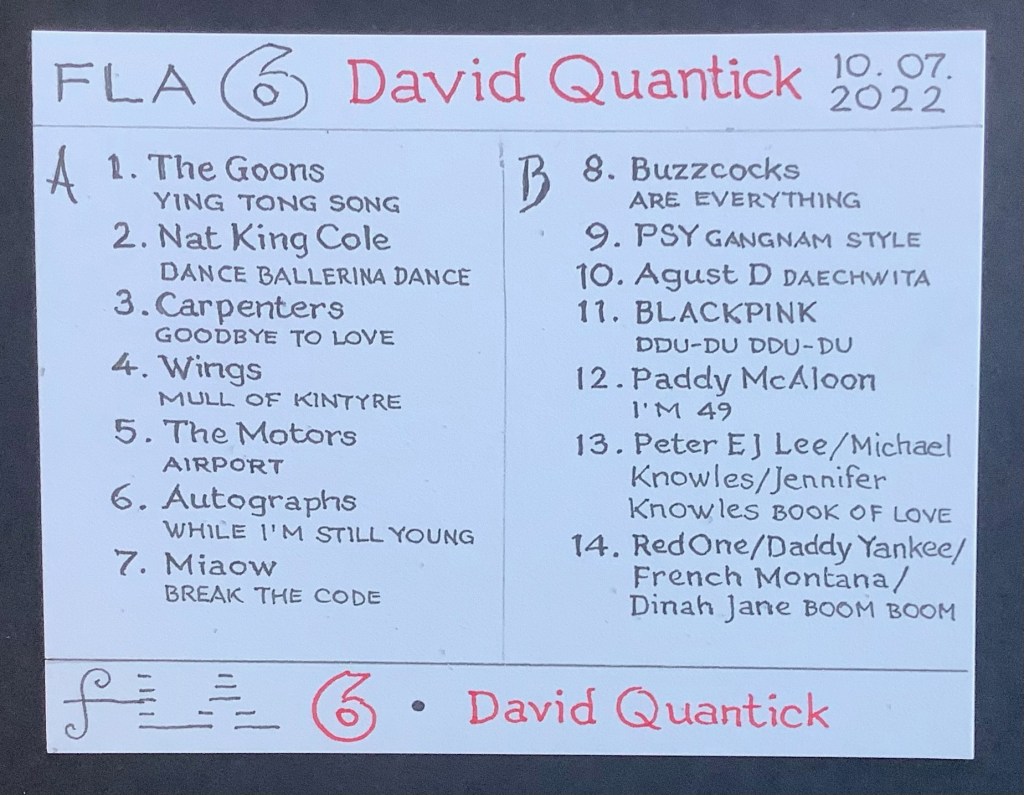

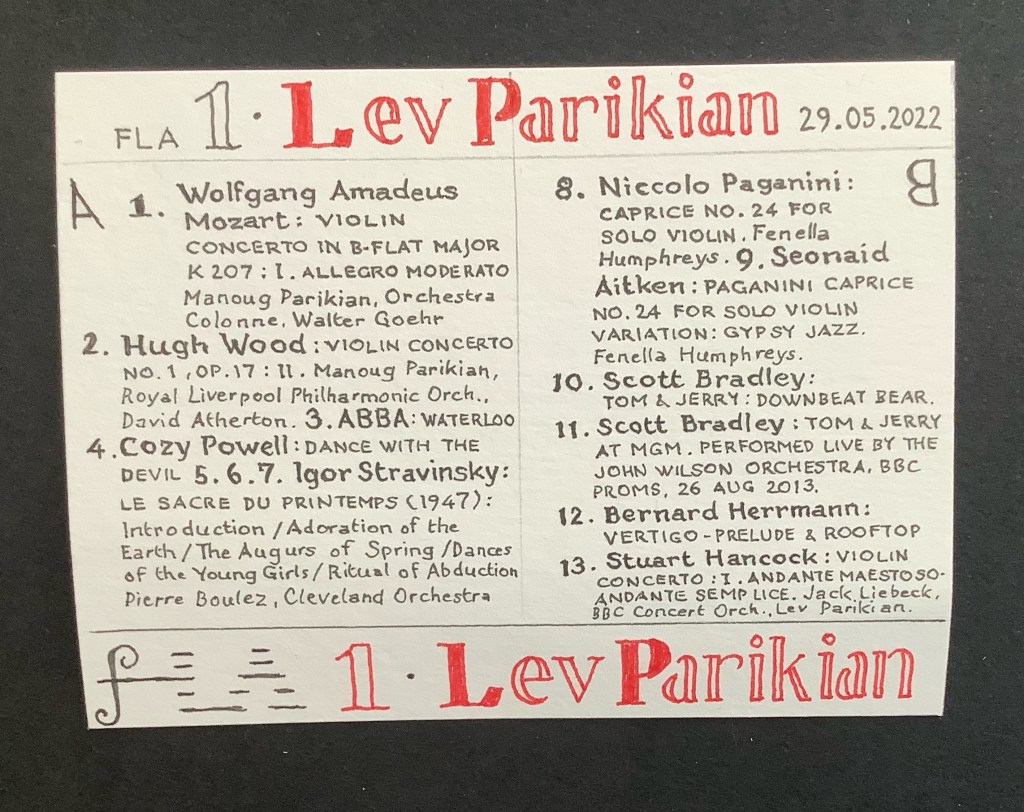

FLA Playlist 6

David Quantick

(For the time being, this site and project uses Spotify for the conversation playlists, but obviously I disapprove that Spotify doesn’t pay artists and composers properly, and other streaming platforms are available, as are sites to buy downloads and buy recordings. For consistency, you can also listen to the selections via YouTube (where available), and links are provided in each case, below.)

Track 1: THE GOONS: ‘Ying Tong Song’: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=33-fVsL5Kdc

Track 2: NAT ‘KING’ COLE: ‘Dance Ballerina Dance’: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Rlsy4te7jY4

Track 3: CARPENTERS: ‘Goodbye to Love’: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YarvI9eCa8Q

Track 4: WINGS: ‘Mull of Kintyre’: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Plhtk_XJqhM

Track 5: THE MOTORS: ‘Airport’: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=aS7dnNVidjA

Track 6: THE AUTOGRAPHS: ‘While I’m Still Young’: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=o5xBh8ELOfY

Track 7: MIAOW: ‘Break the Code’: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9gzX2kNa7O4

Track 8: BUZZCOCKS: ‘Are Everything’: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fNX59sdaPcw

Track 9: PSY: ‘Gangnam Style’: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cGc_NfiTxng

Track 10: AGUST D: ‘Daechwita’: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8TWQg4z9Ic8

Track 11: BLACKPINK: ‘DDU-DU DDU-DU’: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IHNzOHi8sJs

Track 12: PADDY McALOON [now credited to Prefab Sprout]: ‘I’m 49’: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cenwtYd7HFo

Track 13: PETER EJ LEE, MICHAEL KNOWLES, JENNIFER KNOWLES: ‘Book of Love’: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QCg3PQuTNzw&list=PLyW-9UYLk9O2fSb_HYzGfl45t771DSTvD

Track 14: RED ONE, DADDY YANKEE, FRENCH MONTANA AND DINAH JANE: ‘Boom Boom’: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2a4gHAiXo7E

This blog has been almost entirely dormant this past year. The short answer is, I’ve been busy elsewhere.

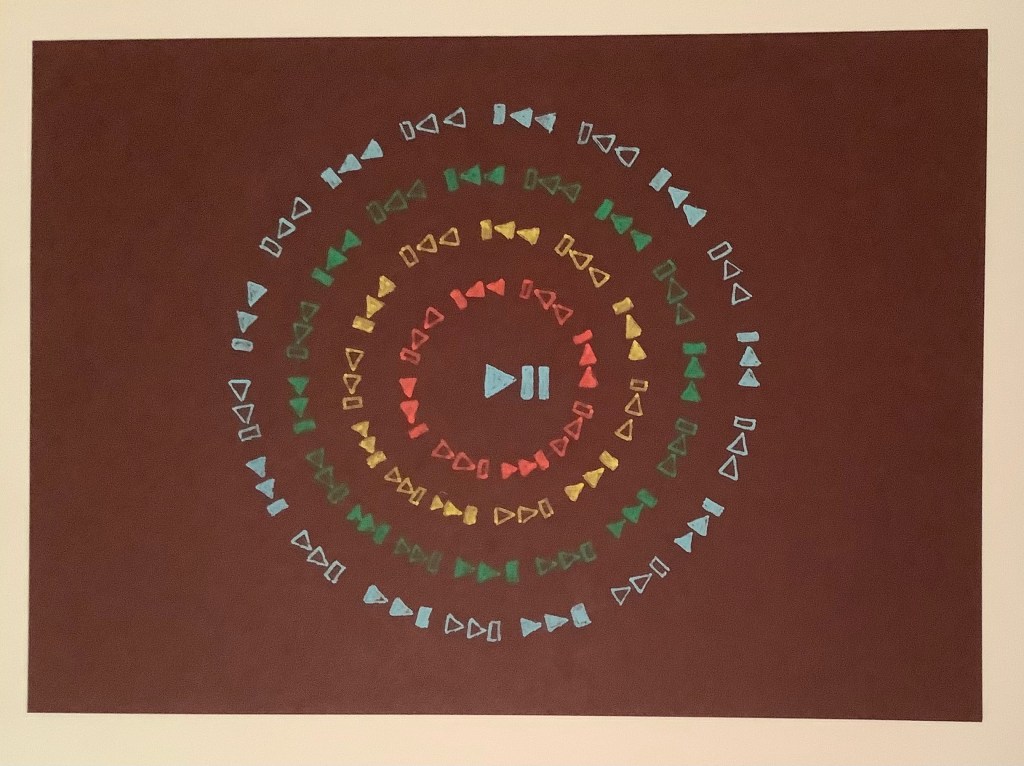

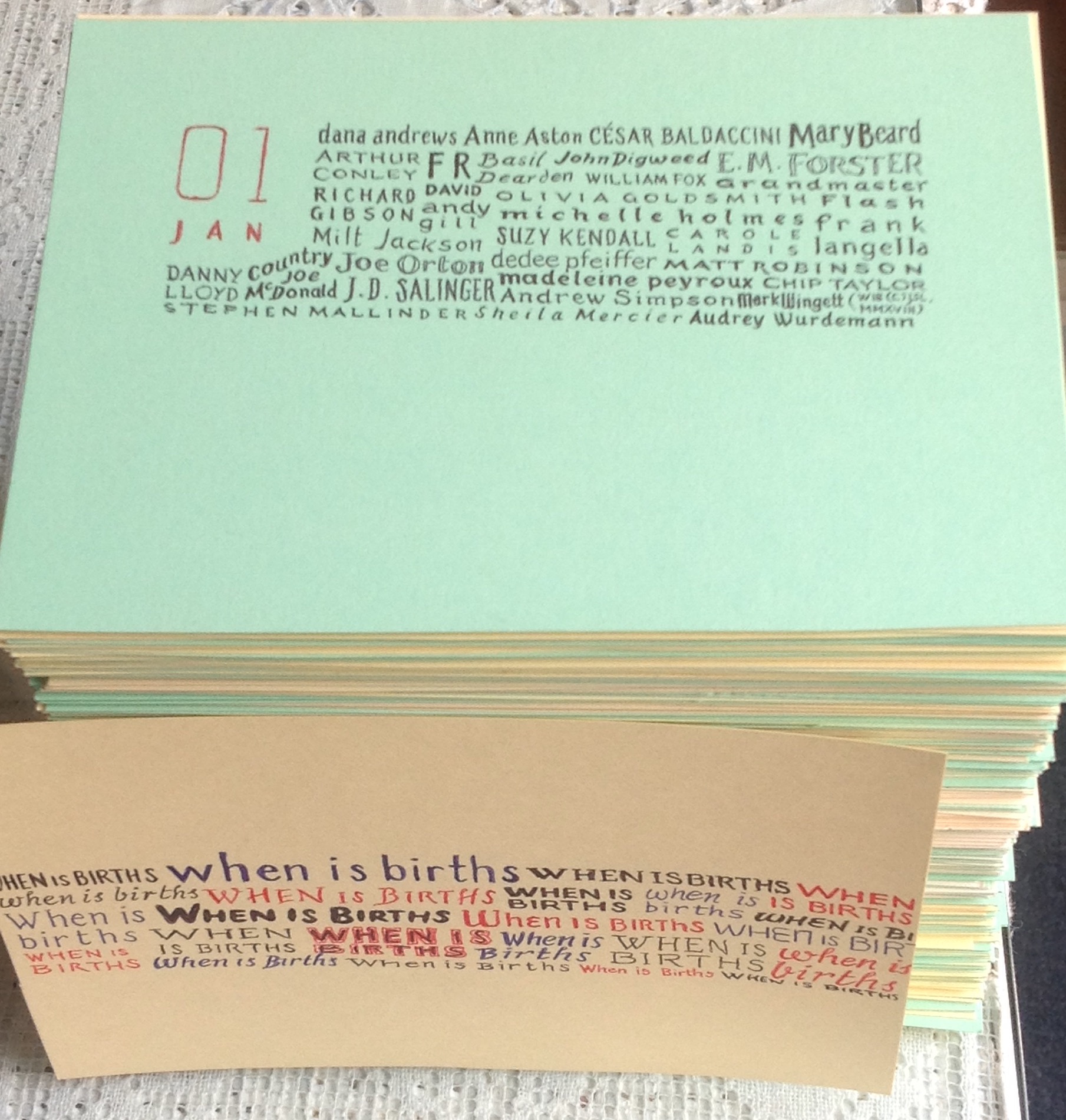

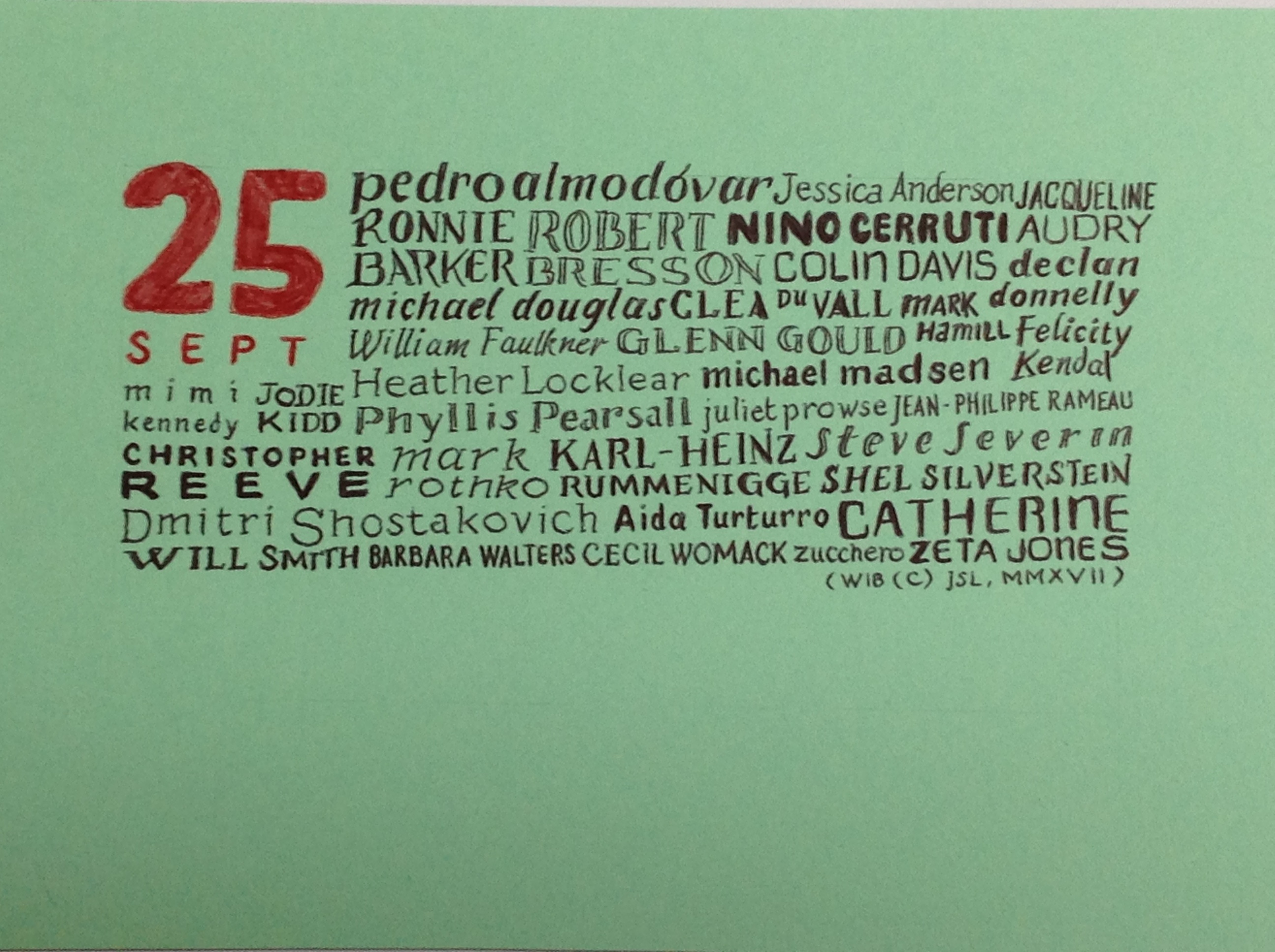

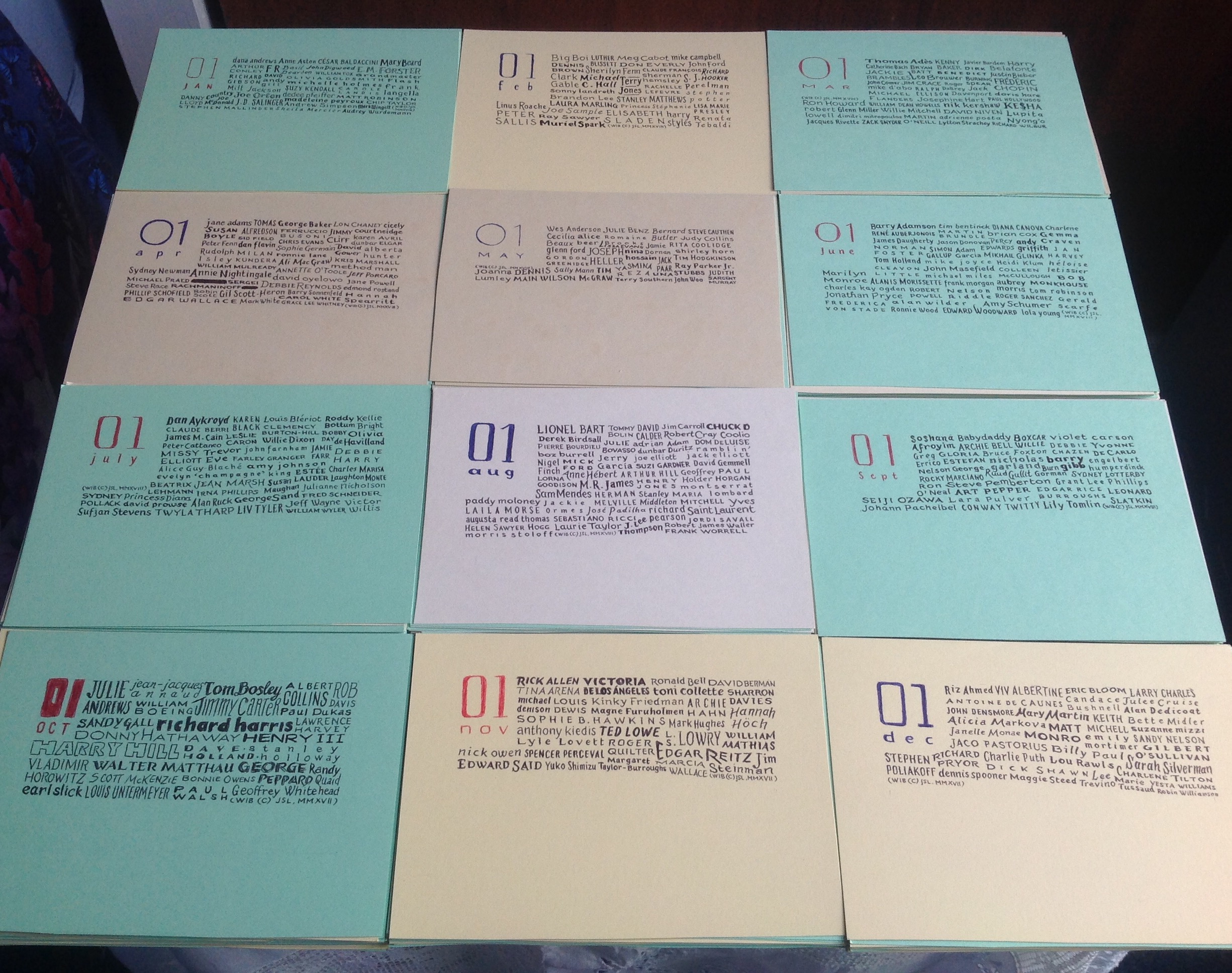

This blog has been almost entirely dormant this past year. The short answer is, I’ve been busy elsewhere. I have to tell you, it’s nerve-wracking when you’re about to launch anything, especially when you know it’s going to take up a lot of your time. But I was right to say nothing ahead of launch day, I think. Because it would be an image, it seemed free of one specific interpretation. If someone wanted to just glance at it for a few seconds, that was fine; equally, you could read all the names and count up how many you recognised; you could even, if you wished, investigate the unfamiliar names, and seek out clips, songs and reading matter. I liked this most of all. And because everyone has a birthday, everyone gets a turn. Lastly, I chose to list the names for each day in alphabetical order, not least because it seemed the best way of accidentally ensuring amusing juxtapositions.

I have to tell you, it’s nerve-wracking when you’re about to launch anything, especially when you know it’s going to take up a lot of your time. But I was right to say nothing ahead of launch day, I think. Because it would be an image, it seemed free of one specific interpretation. If someone wanted to just glance at it for a few seconds, that was fine; equally, you could read all the names and count up how many you recognised; you could even, if you wished, investigate the unfamiliar names, and seek out clips, songs and reading matter. I liked this most of all. And because everyone has a birthday, everyone gets a turn. Lastly, I chose to list the names for each day in alphabetical order, not least because it seemed the best way of accidentally ensuring amusing juxtapositions.

Michael Cumming is one of British television’s foremost comedy directors. Over the past twenty years, the Cumbrian has worked with Mark Thomas, Lenny Henry, Rory Bremner, Matt Lucas and David Walliams, Matt Berry, and Stewart Lee. But his career in comedy began in the spring of 1995. Chris Morris’s Brass Eye, which took eighteen months to complete, drew on Cumming’s versatility on a wide range of programmes, from documentary inserts to corporate videos, from children’s magazine shows to Channel 4’s post-pub yoof sneeze, The Word. His wide range of experience gave Morris’s project – somewhere between experimental media satire, sketch show and hidden camera – an authenticity. As with The Day Today, Morris’s previous series with Armando Iannucci, Brass Eye didn’t look like a comedy show.

Michael Cumming is one of British television’s foremost comedy directors. Over the past twenty years, the Cumbrian has worked with Mark Thomas, Lenny Henry, Rory Bremner, Matt Lucas and David Walliams, Matt Berry, and Stewart Lee. But his career in comedy began in the spring of 1995. Chris Morris’s Brass Eye, which took eighteen months to complete, drew on Cumming’s versatility on a wide range of programmes, from documentary inserts to corporate videos, from children’s magazine shows to Channel 4’s post-pub yoof sneeze, The Word. His wide range of experience gave Morris’s project – somewhere between experimental media satire, sketch show and hidden camera – an authenticity. As with The Day Today, Morris’s previous series with Armando Iannucci, Brass Eye didn’t look like a comedy show.