What makes you laugh on television? Maybe it’s Xander and Richard bantering on Pointless. Maybe it’s the dog acts on Britain’s Got Talent. Maybe it’s the esoteric songs they choose for Homes Under the Hammer. Maybe it’s when they say ‘soggy bottom’ on Bake Off. Maybe it’s Danny Dyer’s episode of Who Do You Think You Are? Maybe it’s when Phil and Holly get the giggles on This Morning because one of them said ‘knob’ in another context, somehow. Or maybe it’s one of the remaining Actual Comedy Programmes that shiver in the schedules due to lack of company and clothing.

Half my life ago now, one sweltering day in July 1995, I attended a final board at BBC Radio, for a position as a trainee comedy and entertainment producer. It was an exciting time for comedy: the BBC Radio and Television entertainment departments were growing closer together. Many radio series had successfully transferred to television – The Mary Whitehouse Experience, Have I Got News for You, KYTV, Room 101, The Day Today – with many more still to come. And the trainee producer candidates were likely to work in both media. I faced five (it may even have been six) people in that interview room. An exciting but scary experience.

There were four trainee producer positions available. I came in fifth or sixth, I think, probably due to lack of directing experience or simply that the others were better candidates. They would join a department that was nurturing shows like People Like Us, The League of Gentlemen, Goodness Gracious Me!, and later Dead Ringers and Little Britain. I licked my wounds, and applied instead for office jobs and hackwork.

In the 1990s, with a massive number and range of comedy programmes on television, it felt like the torrent would never end, and this was still before the invention of PlayUK, E4 and BBC Three, who all invested in original comedy. Twenty years on, TV comedy seems on the fringes. In one way, there’s no shortage of them, but they’re scattered around the edges: iPlayer, Sky, Netflix, Amazon Prime. Only Harry Hill, these past six weeks, has been able to sneak a designated comedy show into pre-watershed hours on terrestrial television, and even his Alien Fun Capsule, which is great fun by the way, needs the facade of a panel show, despite being nothing of the sort on closer inspection. Comedy is expensive and risky, and so a lot of broadcasting couches ‘funny bits’ within other kinds of entertainment format: competitions, lifestyle, reality TV.

But everyone still thinks they’re a comedian, and some like to pretend that provocation is the same as telling a joke. Ersatz ‘comedy’ often survives in bastardised forms, such as the output of the tabloid columnist or a front page headline: you write a shit pun, one which doesn’t even work, you punch down at a minority or at least people who are ‘different’ from you, and then after jokelessly causing offence, you switch to disingenuous and wonder why people are causing such a fuss. Sarah. It’s easier to get attention by enraging them than by entertaining them.

There have been, of course, some great newspaper columnists, but many are, like me, people who would have died on their arse in open spot after open spot. A columnist on a comedy panel show is frequently and embarrassingly at sea, discovering that, when voiced aloud, their aggravating gallery-playing shtick turns to gravel in their own mouth. In the distance, a lone owl coughs, and Paul Merton has to step in. Even Alexander Johnson had to work from an autocue after his first Have I Got News for You appearance.

The columnist’s attitude of bleak bravado has spread to social media. The more shrill posters there – who tend to type with their nose or whole arm – have to stress that they’ve made a joke, using that peculiar crying/laughing emoji, when in fact they mean that they’ve just said something they can’t begin to defend.

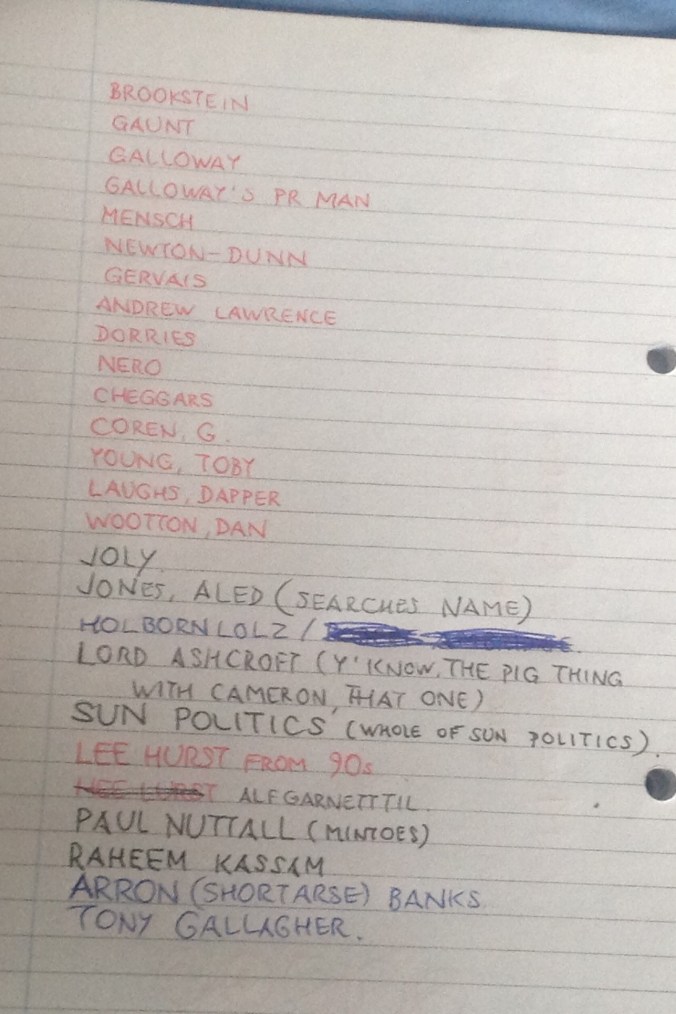

Then again, my relationship with Twitter is not entirely innocent. For a while it seems liberating. It’s liberating to dismiss provocative figures in kind: to liken Quentin Letts to the Viz character Spoilt Bastard; to describe the head of The Sun’s editor-in-chief Tony Gallagher as looking like ‘a dented football trophy from the 1930s that’s just been dug up’; to call Paul Dacre ‘a putrified testicle’; to call Theresa May ‘a Londis Thatcher who attended elecution classes and said “Make me sound like the cane from school”’; to wonder why Alexander Johnson and Donald Trump seem to want to look like Jimmy Savile first thing in the morning.

All of this is cathartic, briefly, I suppose. But then the excitement cools and sours and you feel resigned and powerless. It’s not funny anymore, you feel tired, and then the next day’s news comes, and it’s more dung, and the dung is even worse. It’s as if your attempts at being funny didn’t change stuff.

Because Twitter is so transitory, it’s not just easy to become addicted to it (nods), it also has no shape, no finity. If only one could channel its funniest, most dynamic components into a TV concept, for funny, engaging contributors. (Note: I am certainly not suggesting a TV show about Twitter – the only time TV entertainment really used the Internet effectively was on So Graham Norton, which was pre-broadband.)

But I think there’s another problem with Twitter and again, I’m as guilty as anyone. We all have our Twitter character now, and a tweeting style, and we can be prone to catchphrases and memes and hobbyhorses. And if you’re a heavy user of Twitter (nods), you risk becoming reliant on saying a thing just to say something, anything. You are Mumbler3, hence: bins, Pacman Ghosts, pop trivia. You start to become bored of your own language.

On the other hand, Twitter has been a constant companion to me over the past seven or eight years, through self-employment, bereavement (twice), anxiety, depression and isolation. It’s also made me laugh a lot, and there are close friends I would never have met without it.

But one reason I started this blog at all was to expand Twitter thoughts into something more fully-formed and ‘permanent’, if a blog can have permanence. Mind you, it’s been tricky to write much lately without interrupting with BUT SO WHAT in big capital letters. It’s because the enormity of Britain leaving the EU with so few concrete ideas about how and even why it is doing so (and real solutions, please, not just that Union Flag you jammed in your arse last June, thanks) has given us a sense that not only is the past far away, but so is the future – and so is the present.

We need to step back from the edge. Idiots must not set the agenda. We want real clowns. We need incisive, thoughtful comedy back at the centre of things. Partly to entertain us, but partly to make sense of it all.

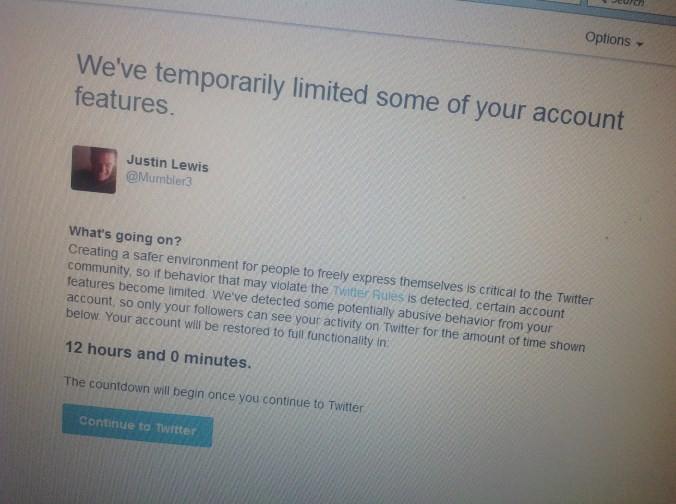

This morning I did the same to Nigel Farage, who claimed that Malmo was ‘the rape capital of Europe’, presumably another piece of research from the Otterglans team. So I told him to ‘cunt off, you ashen liar’. I’ve dreamed up better insults, I know (for instance when I called him ‘a grasping dead-eyed toad of shit’), but I stand by it. And I appreciate that not everyone likes the c-word, even though according to research at the University of Otterglans, it is by far the best, most effective swear word. The point is, his tweet – extremely unpleasant, and designed purely to stir up ‘debate’ – is allowed to stand. My response seemingly is not. Which leads me to wonder: are people cautioned for insulting the disabled, for racist language, for Nazi support?

This morning I did the same to Nigel Farage, who claimed that Malmo was ‘the rape capital of Europe’, presumably another piece of research from the Otterglans team. So I told him to ‘cunt off, you ashen liar’. I’ve dreamed up better insults, I know (for instance when I called him ‘a grasping dead-eyed toad of shit’), but I stand by it. And I appreciate that not everyone likes the c-word, even though according to research at the University of Otterglans, it is by far the best, most effective swear word. The point is, his tweet – extremely unpleasant, and designed purely to stir up ‘debate’ – is allowed to stand. My response seemingly is not. Which leads me to wonder: are people cautioned for insulting the disabled, for racist language, for Nazi support? When I first went on Twitter, probably around the middle of 2009, livetweeting disposable TV shows was an attraction of the site. Question Time was undoubtedly one of these. But it gradually became an endurance test where not even Twitter accompaniment could detract from its deathly formula of rehearsed quips, point-scoring and gassy pub opinions you hoped had been silenced with the progress of civilisation.

When I first went on Twitter, probably around the middle of 2009, livetweeting disposable TV shows was an attraction of the site. Question Time was undoubtedly one of these. But it gradually became an endurance test where not even Twitter accompaniment could detract from its deathly formula of rehearsed quips, point-scoring and gassy pub opinions you hoped had been silenced with the progress of civilisation.