(c) Josefina Melo

Jonathan Coe, born in Bromsgrove near Birmingham in the early 1960s, is one of the great contemporary comic chroniclers of British life and society. His highly enjoyable, incisive and thoughtful novels frequently include material about films, television, politics, the media – and from time to time, music, of which he is an enthusiastic listener and sometime participant.

He read English at Cambridge University’s Trinity College at the turn of the 1980s, before completing an MA and PhD at the University of Warwick. His first novel, The Accidental Woman, was published in 1987, and his subsequent acclaimed titles have included What a Carve Up! (1994), The House of Sleep (1997), The Rotters’ Club (2001) and its sequel The Closed Circle (2004), The Rain Before It Falls (2007), The Terrible Privacy of Maxwell Sim (2010), Expo 58 (2013), Number 11 (2015), Middle England (2018) and Mr Wilder and Me (2020).

I should also mention here that Jonathan wrote one of the most remarkable literary biographies I have ever read: Like a Fiery Elephant: The Story of BS Johnson (2004), which won the Samuel Johnson Prize for Non-Fiction the following year.

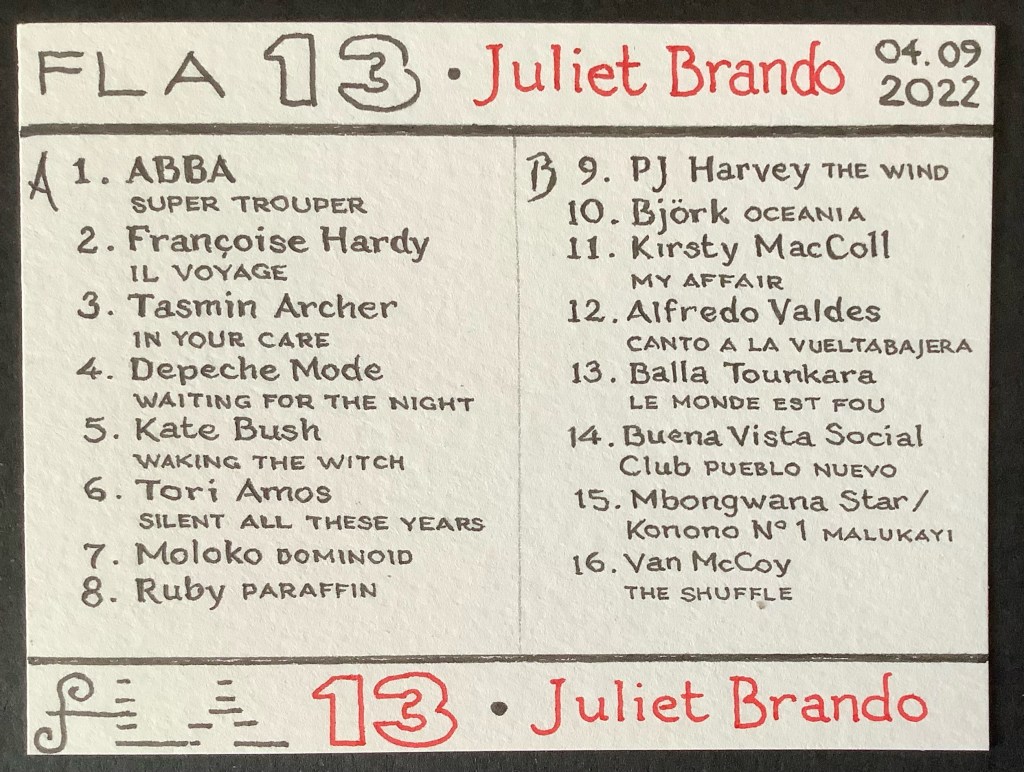

Jonathan is one of my favourite authors, and I have met him in person a few times, so you can imagine what a thrill it was for me when – with the impending publication of his fourteenth novel, Bournville, this autumn – he accepted my invitation to come on First Last Anything. We discuss his love for progressive rock and French classical music, as well as how he began creating music of his own in his teenage years, and why music can be more powerful than words.

It felt like the ideal way to end this first run of FLA, although may I assure you it will return, in 2023. I hope you’ve enjoyed all these conversations. Thank you for reading them. And thank you to all my guests.

—-

JUSTIN LEWIS

When you were growing up, before you started buying music yourself, what music did your parents have in your house?

JONATHAN COE

My main memory is easy listening. Radio 2 would be on – this is in the 60s.

JUSTIN LEWIS

Was this pre-Radio 1, when it was still the Light Programme?

JONATHAN COE

I suppose so. Radio 1 started 1967. But the first piece of music I can remember my parents having on single and me liking, was ‘Tokyo Melody’, the theme music – probably the unofficial theme music – for the 1964 Tokyo Olympics, by a German guy called Helmut Zacharias. That was on heavy rotation in our house at that time. So I would have been three.

I also have a memory, probably my earliest memory, of being in a pushchair, and my mother singing a Beatles song as she pushed me down the street, but maddeningly, I can’t remember whether it was ‘I Wanna Hold Your Hand’ or ‘She Loves You’. It was one of those two – probably ‘I Want to Hold Your Hand’.

The first piece of music that I can really remember getting excited about, which was as much a visual as a musical thing, was seeing Arthur Brown singing ‘Fire’ on Top of the Pops in the summer of ‘68, when I was seven. That just blew my mind. I’d never seen or heard anything like that.

JUSTIN LEWIS

It’s quite an arresting sight, that ‘Fire’ clip, one of the very few Top of the Pops extracts from the 60s that still exists in the archive. I’m trying to imagine seeing that at the age of seven.

JONATHAN COE

Yes, it was the sight of Arthur Brown in his flaming helmet, but also the music as well – the heavy organ sound, that sinister Gothic sound, which I suppose set me on the road to prog, in a way.

JUSTIN LEWIS

There’s a fork in the road in popular music around 1968, isn’t there: pop or rock. There was another fork in about 1986: house and hip-hop or everything else. But there definitely seemed to be that crossroads in ’68.

JONATHAN COE

Although I then did go into pop, because I became a huge Marc Bolan and T Rex fan in the early 70s, my first real musical love. My first gig, in fact, was T Rex at the Birmingham Odeon in ’74. Just on the decline, after his glory days.

JUSTIN LEWIS

I guess by ‘74, the mass of teen pop had moved on to… The Osmonds, David Cassidy, and then the Bay City Rollers a little bit later.

JONATHAN COE

‘71–‘73 was the peak for T Rex but I worshipped them during those years. When I saw them [28/01/1974], Marc’s trousers were so tight that they split on stage, causing great excitement in the audience.

JUSTIN LEWIS

Given you saw T Rex in Birmingham, it made me think about the closing ceremony of the Commonwealth Games recently, and how they had a really wide range of Midlands bands from down the years: Black Sabbath, Dexys, Goldie, Musical Youth…

JONATHAN COE

UB40?

JUSTIN LEWIS

Of course. But it made me think how Birmingham isn’t necessarily viewed as this big musical hub, the way Liverpool or Manchester or Sheffield are.

JONATHAN COE

Well, all the names you’ve mentioned there, from Birmingham, have nothing in common really, musically. Richard Vinen has just published this big book about Birmingham, Second City and he devotes quite a few pages to the musical scene in the 70s and 80s, and it’s just very heterogenous, you know? I was never a Sabbath fan, but I would have liked The Moody Blues. And later on, Duran Duran, Dexys… there’s no real ‘movement’ there. More a coincidence that they all came from the same city.

One local musical celebrity who doesn’t get talked about much anymore was Clifford T. Ward (1944–2001), the singing schoolteacher who taught at the same school as my mum for a while. He had a hit with ‘Gaye’, and he was a really good singer-songwriter. There’d be stories about him in the Bromsgrove Messenger.

I grew up in Worcestershire, in the Lickey Hills, and didn’t know then that Roy Wood, from The Move and briefly one of the ELO’s founder members, before forming Wizzard, literally lived a mile away from us, down the road in Rednal. I would not even have known that the ELO came from Birmingham.

FIRST: THE ELECTRIC LIGHT ORCHESTRA: ELO 2 (Harvest, 1973)

Extract: ‘From the Sun to the World (Boogie No. 1)’

JONATHAN COE

At the age of 10, or so, I was a retro rock’n’roll fan. My grandparents had an original 78 of Bill Haley’s ‘Rock Around the Clock’, and this was a kind of sacred object in our family mythology, which we assumed was worth thousands and thousands of pounds. So I bought a Bill Haley compilation on Hallmark Records [Rock Around the Clock, 1968] and I also got into Chuck Berry, just buying greatest hits albums, so I knew his song ‘Roll Over Beethoven’. And then [in early 1973] I heard this weird version of ‘Roll Over Beethoven’ which started with that clip from Beethoven’s Fifth, which turned out to be by the ELO.

So I thought, Great, I love this, I’ll buy the whole album on cassette – my preferred format back then. I had no idea that what I was buying with ELO 2 was a full-blown prog album, just five tracks, all about ten minutes long, and with lots of time signature changes. And all this did something strange to my ears. I thought, ‘I want to hear more music like this’, and ‘Roll Over Beethoven’ quickly became my least favourite track on the album. So I got into all the other stuff, and I suppose I was a bit disappointed when Jeff Lynne took the band in a much poppier direction.

JUSTIN LEWIS

One of the earliest memories of TV I have – and I’ve never been able to confirm it – is that one afternoon, for some reason, there was an ELO concert on BBC1. Maybe they’d cancelled something at the last minute, sports coverage or something, because I’ve never found what it was or why it was on. This was 1975, maybe ’76. I was five or six.

I don’t think I’d ever seen a rock concert on television before, actually. I know now that ELO had done a live LP in America, and there’s something on YouTube they did for German television, but how on earth would that have been on BBC1 in the afternoon? It’s one of those half-memories you can’t nail down. I feel like that character in your novel Number 11.

JONATHAN COE

The one who’s looking for the lost film, yeah.

JUSTIN LEWIS

So how did you fall for prog? I think you particularly gravitated towards the Canterbury Scene, right?

JONATHAN COE

The big prog bands I never particularly liked. I never had any Emerson Lake and Palmer album or Yes album – although my brother was into Rick Wakeman, so we had his solo albums. I immediately went for the fringes of prog, and in a way that chimes with my taste anyway. I always seem to be drawn to the fringe figures, who seem to then become the major figures for me.

I suppose my entry point there was The Snow Goose by Camel (1975). I can’t remember how that became such a desired object for me. I think there was a buzz around it at school. I can remember seeing it in the local WHSmiths in Bromsgrove, and I circled it for weeks and weeks thinking, Am I going to buy this album or not? Eventually I did. I really liked that record and still do.

On Radio 1, I was listening to John Peel, but also the Alan Freeman Saturday afternoon rock show which played a lot of Gentle Giant, Soft Machine, Caravan. Like a lot of people, my gateway drug to the Canterbury Scene was Caravan because they were popular and more melodic and more accessible. I heard ‘Golf Girl’ one night on the John Peel show and a Caravan compilation album had just come out, Canterbury Tales (1976), which included ‘Memory Lain, Hugh’, a particular favourite. Around that time, Pete Frame did a ‘Rock Family Tree’ of the Canterbury Scene, which suggested so many connections that it gave me my record-buying programme for the rest of the 70s.

JUSTIN LEWIS

Those incredibly detailed, beautifully realised Pete Frame Rock Family Tree illustrations were like a forerunner of the Internet, a way to make musical connections.

JONATHAN COE

Yes, you could piece it together, I suppose, by reading the music press, but those Family Trees were the only places where all the information was gathered in one place. Another thing that gave you a lot of information in one place was a book called The NME Book of Rock (1975, edited by Nick Logan and Rob Finnis), which was sort of the first British pop reference book, as far as I remember. I had a couple of paperback editions of that.

But yeah, as you say, otherwise, your findings and your quests for this kind of music were very random and haphazard, which in itself was part of the pleasure, of course. There’s this perpetual debate about whether it’s better to be able to find things within five seconds with one click, or whether it’s more exciting and romantic to have to traipse around half a dozen record shops looking for something.

JUSTIN LEWIS

It’s been interesting for us to have both those experiences. They both have good points and bad points.

JONATHAN COE

Generally speaking, I think, as consumers, as punters, we’re better off now. It’s probably not as good for the musicians, of course.

JUSTIN LEWIS

I’m trying to avoid analysing anything in your novels as autobiographical, but I was thinking about that section in The Rotters’ Club, itself named after a 1975 Hatfield and the North album lest we forget, where Benjamin visits the NME building. Did you ever do anything like that in your teens, try and get into the music press in that way?

JONATHAN COE

No. Absolutely not. I’ve seen it reported that I was one of the people who applied for the NME ‘hip young gunslinger’ job that resulted in them hiring Julie Burchill and Tony Parsons, but it’s not true. I was so untrendy back in the 70s – still am, really. I wasn’t even an NME reader or a Melody Maker reader. I was a Sounds reader. Before it turned into a kind of full-blown heavy metal paper in the late 70s, Sounds was good for Canterbury Scene stuff. It wasn’t as snobby about that as the NME was, or as serious and muso-ish as the Melody Maker was. And John Peel had a column in Sounds back then, which I have to say was a big influence on my writing style. It was one of the highlights of my reading week.

JUSTIN LEWIS

And he used to review the singles in Sounds quite often, didn’t he? He backed quite a lot of singles you might not expect him to have done. You may remember he had a nickname for Tony Blackburn, ‘Timmy Bannockburn’…

JONATHAN COE

That’s right.

JUSTIN LEWIS

Once he reviewed ‘I Can’t Stand the Rain’ by Ann Peebles, and mentioned it had been ‘Timmy Bannockburn’’s Record of the Week on the Radio 1 breakfast show, and with some sincerity said something like, ‘Quite right too’.

JONATHAN COE

One single I was obsessed with in the 70s was ‘I’m Still Waiting’ by Diana Ross, which I also heard on the Tony Blackburn show. He used to play that a lot.

JUSTIN LEWIS

That came out as a single because of him. He’d been playing it as an album track and persuaded the Motown label in Britain to put it out as a single. Funnily enough, that single wasn’t a success in America at all, and nor was her other British number one, ‘Chain Reaction’.

JONATHAN COE

I had a real fascination for those rare, occasional, slightly melancholy minor key songs that made it into the British charts. ‘Long Train Running’ by the Doobie Brothers is another song I’ve always loved – again, there’s a minor key.

JUSTIN LEWIS

On the subject of ‘I’m Still Waiting’, those records in the early 70s where they use orchestras, especially woodwind. You hear lots of oboes on American soul records. That Stylistics record, their best one really, ‘Betcha By Golly Wow’.

JONATHAN COE

I bought very few singles in the 70s. I was an album buying person, but you’ve just reminded me, I did like ‘The Poacher’ by Ronnie Lane, precisely because it has a beautiful oboe figure, running, running through the song that grabbed my attention immediately.

Though clarinet and bassoon, there’s not so much of those on pop records. ‘Tears of a Clown’, that’s got a bassoon.

JUSTIN LEWIS

I’m trying to think. [During the editing of this piece, I discovered that the bassoon on ‘Tears of a Clown’ was played by Charles R. Sirard (1911–90), from the Detroit Symphony Orchestra. I also suddenly remembered a second number one hit featuring a bassoon: ‘Puppet on a String’. It feels a shame that there aren’t more bassoons in pop music.]

—

JUSTIN LEWIS

You mentioned in one piece of writing, a while back, that your ideal early profession was ‘composer’. Obviously, that’s interesting given that you write novels, have done for decades. I’m struck by the similarities and differences between composing and writing. They can both liberate you in different ways. They can both do something that the other cannot. Is that how you feel about the two things, and were you composing in the early days, as well as trying to write novels?

JONATHAN COE

The key thing is that I was intensely shy as a teenager. Part of the reason I went for fringe music, I think, was to sidestep all the musical arguments that were going on at school, and not be a part of that. I could like bands that no-one could criticise me for liking because they’d never heard of them and they didn’t know what they sounded like. The other kids at school were forming bands, but I couldn’t really handle that social dimension of rehearsing together in a room and asking people to join.

I was having classical guitar lessons, and my teacher wanted us to play a duet, so I started wondering how to practise for it, between the lessons. I had an ITT portable cassette player, recorded my teacher’s part on the tape, and then played along with it. As soon as I did that, I realised: Wow – even if I can’t play in a band, I can play with a tape recorder. And then if I get another tape recorder, and recorded those two parts, then I could bounce them down and then start multitracking. So I started working on these ever more elaborate duets – at first – and then trios, and then quartets. And then my mother traded in her piano for an electric home organ, so we had one of these terrible home organs in the corner of the sitting room.

I never composed, really, because although I can read and write music on paper, I find it a very difficult, time-consuming process. But when I started multitracking, in the mid-70s, and I was modelling myself on Mike Oldfield – who wasn’t one of my favourite artists, but I did like his records. And that’s what I realised I was doing: solo composed and solo performed music. I carried on doing that for years, until the late 80s when my first novels started getting published. And I still have all these recordings from that period, which I’ve digitised, so there’s about 40 or 50 hours of music there – in terrible sound quality. [Laughs]

JUSTIN LEWIS

And there are three albums of your compositions that are out there now.

JONATHAN COE

On my bandcamp page, there are two albums, if you like: Unnecessary Music and Invisible Music. And there’s a little EP of other pieces an Italian producer heard and remixed. But what I must talk about for a few minutes is something incredible that’s happened in the last couple of years:

Those bandcamp albums are mainly digital re-recordings of some of those old pieces, and an Italian musician, a drummer and bandleader called Ferdinando Farao, heard them and liked them. He runs a twenty-piece orchestra in Milan called the Artchipel Orchestra, and they specialise in doing big band arrangements of Canterbury music, Robert Wyatt and Soft Machine tunes and so on. And to my amazement, they took half a dozen of these pieces and did new arrangements of them – and they’ve performed them four times in concert now. The last time was in Turin in June this year. They even persuaded me to come on stage and play keyboards with them. So finally, in my sixties, I’ve become a live performer. There’s a little clip of the Turin show on YouTube. It was a fabulous night, one of the best nights of my life:

JONATHAN COE & ARTCHIPEL ORCHESTRA at Torino Jazz Festival, 12 June 2022

JUSTIN LEWIS

The first novel of yours I ever read was The House of Sleep in May 1998. I was given the beautiful hardback edition of that as a birthday present, and tore through that, and then I quickly worked backwards, bought and read What a Carve Up!, and then your much earlier, first three novels – which were quite hard to find at that point.

I wanted to ask you about two of those very early novels because they both touch on the subject of music. In your first novel, The Accidental Woman (1987), there’s a footnote near the end of the book which says, ‘Instead of reading this section, you should just play the end of the first movement of Prokofiev’s Violin Sonata in F Minor.’ Now, at the time, I didn’t see this as a joke at all – but I was not in a position to take it completely seriously, on the grounds that I had no immediate access to this piece of music! [JC chuckles] More recently, I’ve been able to read it again and play that sonata – thanks to the Internet. Does it feel strange to look back at your pre-Internet work with the sense that things were out of reach at the end of the last century?

JONATHAN COE

Well, there’s a couple of things there. It’s very interesting that you read that passage in The Accidental Woman in 1998. Soon after that, Penguin bought the rights to those books and reissued them, in 1999 or 2000.

JUSTIN LEWIS

Yes, I think my copy was published by Sceptre.

JONATHAN COE

And for those Penguin editions, which are the editions now still in print 22 years later, I changed that passage; I looked at it again and thought that was a bit pretentious and wanky. But now I’d like to change it back because I kind of stand by it! In the Penguin edition, it just says something like ‘At this moment, what was running through Maria’s head was the last movement of Prokofiev’s Violin Sonata.’ Whereas, in the (original) Duckworth version and Sceptre version, it actually says to the reader, in a footnote, ‘Don’t read this, just listen to this piece of music instead.’ Which is more what I really meant, because of the tone of the book – it sounds like a kind of arch joke. But actually, I was perfectly serious about it.

What I was trying to express there, was that you can say something much purer and more powerful in music than you can in words. It’s as simple as that, really. Words get in the way because they carry meaning, they’re semantic, whereas music brings you much closer to the emotion that the composer is trying to express. So the music that I play or improvise – because I’m kind of embarrassed to use ‘compose’ – and the books that I write are actually completely separate from each other. As you may know, I’ve made attempts over the years to combine words with music, working with the High Llamas and with Louis Philippe, always fascinating, enjoyable and fruitful collaborations. But in the end I decided that didn’t really work for me, because the two things, I think, are so different that it’s best to keep them apart.

JUSTIN LEWIS

I must admit, I always sigh with relief slightly when other people who work with words say that they prioritise music over lyrics. [Agreement] Am I right in saying that it’s the music you go for first?

JONATHAN COE

If I’m listening to a song which engages me musically, I just don’t hear the lyrics – the singer might as well be singing ‘lalala’. I don’t notice the words at all. It’s not that I don’t like Bob Dylan, but it’s why I didn’t listen to Bob Dylan because everybody said, ‘He’s a genius lyricist’…

JUSTIN LEWIS

I didn’t get him for years – I do now – on the grounds that he was ‘lyrics first’. But the lyric is the thing I get to last. I probably get the arrangement sooner.

JONATHAN COE

I listen to quite a bit of French pop music – Orwell, for instance – and one thing I like about that is I don’t really know what they’re saying. [Laughs]

JUSTIN LEWIS

It’s incredibly liberating, that. Well, hopefully, they’re not saying something terrible! But you get a sense that really you’re reacting to the sound.

Another of your early novels that I revisited recently, having not read it for a long time, was The Dwarves of Death (1990). And that one was written when you’d actually been in a band in London.

JONATHAN COE

We were called The Peer Group, a band I formed with some student friends in the mid-80s. The idea was to play a jazzy Canterbury, Caravan-y kind of music, but for various reasons, that didn’t work out. We weren’t really skilful enough musicians, I think that was the problem. Because I was writing quite tricksy music in odd time signatures, which I thought was a clever thing to do – so we mutated into sounding a bit like Aztec Camera or Prefab Sprout or The Smiths at their most melodic. Melodic, jangly guitar music, I guess. We did very few gigs, really, I don’t even know whether they got into double figures, actually. We just seemed to rehearse endlessly in cold, draughty South London rehearsal studios, which was the atmosphere I was trying to capture in The Dwarves of Death.

JUSTIN LEWIS

In that novel, you write about the detail of music in a humorous way, without trying to get too bogged down in technicalities. What were some of the challenges there, and do you think you’ll ever write a directly musical novel again?

JONATHAN COE

It’s a long time since I read The Dwarves of Death. I always think of it as my weakest novel, so I don’t like to look at it. But what you’re saying rings a distant bell with me now. There is quite a lot of technical stuff about the writing of music in there, and I think there’s a tune called ‘Tower Hill’, which is threaded throughout the novel, [and which appears in the form of musical notation]. I was very young, you know, and I thought I was being very adventurous and doing something terribly interesting by putting a lot of technical stuff about writing a jazz tune into a novel. It just feels a bit gauche to me now.

If I was to do something like that again, I would do it differently. For instance, Calista in Mr Wilder and Me is a composer, but you hear very little about the kind of music she writes, or how she writes. I think it’s better really to leave it to the reader’s imagination – but I remember being quite insistent at the time with Fourth Estate, the publishers of The Dwarves of Death, that they should include the musical notation in the text, and they were very accommodating about that. Because really I was an unknown writer, it was a low print run, and there was nothing much to lose by doing it. When I met and interviewed Anthony Burgess around that time, I had a copy of The Dwarves of Death with me, and when I showed him the musical notation, he was very jealous: ‘My publishers won’t allow me to put music in my books! How did you persuade them to do that?’ I think it was because, you know, I was just Jonathan Coe; he was Anthony Burgess and there was probably more at stake in his publications!

JUSTIN LEWIS

Not long after I read that book, I discovered BS Johnson, because a friend gave me his novel Christie Malry’s Own Double-Entry as a birthday present, and of course that led me not only to his other books but your terrific biography of Johnson’s life and work, Like a Fiery Elephant (2004). Which I urge everyone to read! In its introduction, you talk about how novelists can put anything into a novel, the form determines it. I used to be obsessed by form, even more than I am now, perhaps. I suspect had Johnson written about music in depth, he might have tried to do something like you did in The Dwarves of Death. I know you were very influenced by him in your early novels – was formal experimentation at the forefront of your mind with that one?

JONATHAN COE

Yeah, subconsciously, that was very much going on, I think. Also, I was young, still in my twenties, and kind of hilariously, I thought of myself as a slightly rebellious literary figure who was going to shake things up. And throwing a whole lot of stuff about music into a novel was part and parcel of that aesthetic for me.

For me, though, what is more significant about The Dwarves of Death: it was the first time I wrote a book where some of the passages read a little bit like stand-up routines. I know this isn’t an interview about comedy, which is my other great love aside from music, but although I was never really going to shake up the form of the novel the way BS Johnson had done – I was never as adventurous as that – I knew I was trying to bring some of the energies of British pop culture, and especially comedy, into the literary novel. Which I think I continued with the next novel, What a Carve Up!, basing it on an old early 60s Kenneth Connor movie of the same name. That was my little stab at doing something new and radical.

JUSTIN LEWIS

One of my favourite things you did in terms of form was the footnotes section in The House of Sleep.

JONATHAN COE

I remember the spur for that. It was about 1996, I was doing some research for The House of Sleep in the British Library, reading a book about sleep. And I just jumped from the number in the text to the footnote at the bottom of the page, and landed on the wrong footnote – and what I read was comically inappropriate. So I thought it would be funny if that happened again and again and again.

JUSTIN LEWIS

It’s brilliant. It feels in a similar spirit to that Two Ronnies ‘Mastermind’ sketch written by David Renwick [BBC1, 01/11/1980] where the contestant keeps answering the question before last.

JONATHAN COE

I never thought about that sketch when I was writing it. I can see the similarity now. But the thing I’ve done that is closer to a Two Ronnies sketch, or was more consciously influenced by them, is the crossword scene in The Rotters’ Club. The character named Sam is trying to do the crossword and his wife is reading the love letter from the horny art teacher, and they’re working at cross purposes. And there is a great Two Ronnies sketch [Christmas special, BBC1, 26/12/1980] – they’re in a railway compartment with the bowler hats on and everything, and Barker is doing The Times crossword, and Corbett is doing The Sun crossword, and the two things keep getting mixed up. Do you not know that sketch?

JUSTIN LEWIS

I should know it. It’s been a while since I’ve properly watched them back.

LAST: LOUIS PHILIPPE & THE NIGHT MAIL: Thunderclouds (2020, Tapete Records)

Extract: ‘When London Burns’

JUSTIN LEWIS

You’ve worked with Louis on and off for many years, and indeed you cited a section of his lyrics in What a Carve Up!

JONATHAN COE

I did, yes.

JUSTIN LEWIS

A song called ‘Yuri Gagarin’.

JONATHAN COE

In the late 80s, when I was in The Peer Group, the student group I mentioned earlier, we were sending demo cassettes around to record labels. And we sent one to Cherry Red, because we thought we sounded like a Cherry Red band. But for some reason, it fell into the hands not of the main label, but to Mike Alway at él records, which was a division of Cherry Red. And he gave a curious kind of response to this; he said, ‘I think you’re trying to sound like a few artists on my label, so here’s a bunch of their records.’ I think he was trying to say, ‘Try and sound a bit more like this.’ The artists were Marden Hill, Anthony Adverse… and Louis Philippe.

I listened to this Louis Philippe record, Appointment with Venus, and just thought it was beautiful. I could hear in it not just the pop sensibility that I loved, but lots of echoes of Ravel and Fauré and Poulenc – my favourite classical composers. So I started following his career and then I wrote to him and asked, ‘Can I use these lines from your song, as an epigraph to What a Carve Up!’ He was very happy about that, said yes, and then a few years later we met at one of his gigs, and became good friends. I wrote some lyrics for a couple of songs on his albums, and then we did a record together for Bertrand Burgalat’s Tricatel label called 9th and 13th (2001). He also made an album called My Favourite Part of You (2002), for which I wrote the lyrics for a song called ‘Seven Years’. He’s now joined up with a band called The Night Mail, and a couple of years ago they made this beautiful album, Thunderclouds.

JUSTIN LEWIS

I’m so glad you’ve recommended this, because I’ve been playing little else, these past few days.

JONATHAN COE

He’s a great songwriter. The strange thing is, he now has this parallel career as a football journalist and this huge following on Twitter.

JUSTIN LEWIS

Football is not something I follow, so I knew nothing about that side of his career!

JONATHAN COE

I’m just so glad that he’s back making records and doing gigs again – as is he, I think.

JUSTIN LEWIS

How do you discover new music now?

JONATHAN COE

I was thinking about this. You know, for everything that the Internet offers us, for me it doesn’t seem to work as a way of discovering new music, unless it’s personal recommendations that people have passed my way on Twitter. But I’m a bit sad and ashamed that I’ve discovered so little new pop music in the last 10 or 15 years really, and a lot of what I have discovered is old stuff that I’ve just never heard before. For instance, I just started listening to Brian Auger – how have I never heard him before? There’s this vast discography to explore, but a lot of it is, you know, 50 years old now. So I rely a lot on the kindness of strangers, really, and people just sometimes sending me CDs that they think I might like. A journalist in Spain a few years ago pressed into my hands a CD by the Montgolfier Brothers. Do you know them?

JUSTIN LEWIS

It rings a bell, but…

JONATHAN COE

Roger Quigley (who died in 2020) and Mark Tranmer, You’d really like them, I think.

JUSTIN LEWIS

Must check them out.

JONATHAN COE

That led me to discover all their records. The person who wrote the music for them is called Mark Tranmer, who also had a band called gnac, who do ambient instrumentals… But it was just a chance encounter with a journalist in Spain who was kind enough to read some of the things I had written about music and think, Oh, maybe Jonathan would like this.

I use the Spotify algorithm and if I like an album on there I will scroll down and click on the other things that it recommends. Sometimes it works – sometimes it doesn’t.

JUSTIN LEWIS

In the past, you’ve described music you listen to when you’re writing, and that’s ranged from Steve Reich to drum’n’bass instrumental music like LTJ Bukem. What seems to work for you during that writing process now, or do you now in fact prefer silence sometimes?

JONATHAN COE

It’s kind of stopped working for me, the idea of listening to music while I write. I nearly always write with silence. Sometimes a piece of music, usually a piece of classical music, will get me into a mood which is appropriate for the scene or the chapter that I’m writing next – but I will then turn it off and write the scene in silence. The way music and writing combine for me now is, I sit here at this desk to write and I have a piano [to my right] so I can swivel around to play the piano if I get bored with writing. So those two activities complement each other, but I rarely listen now to music while I’m writing.

You know, I’ve even become increasingly grumpy about the whole idea of having music on in the background anywhere. Even muzak, library music, lounge music. A lot of thought and creativity and talent and inventiveness goes into that music. And you should sit and listen to it, rather than just using it as background.

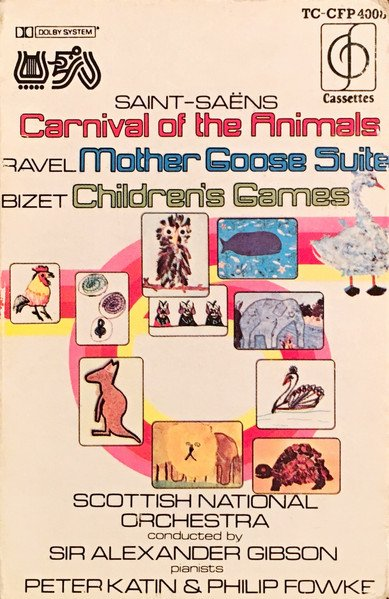

ANYTHING: HELGA STORCK: The Harp and the French Impressionists (1969, Turnabout Records)

Extract: Claude Debussy: Sonata for Flute, Viola and Harp in F Major, L. 137: II. Interlude. Tempo di Minuetto (Wilhelm Schwegler (flute), Fritz Ruf (viola), Helga Storck (harp))

JONATHAN COE

I went to King Edward’s School in Birmingham, quite a posh school, and we had a dedicated music building which was full of practice rooms and a concert hall. And upstairs, there was a place called the Harold Smith Studio. I don’t know who Harold Smith was! But that had a library in it, a record library, and that was where I lived really, for two years in the sixth form, even though I wasn’t studying music at A level or anything like that. Which is where I discovered this record called The Harp and the French Impressionists, which included Ravel’s ‘Introduction and Allegro’ and Debussy’s ‘Sonata for Flute, Viola and Harp’.

I put this on, and just thought it was the most beautiful thing I’d ever heard. And also, all these records I had been listening to, like The Snow Goose by Camel or certain Genesis albums… I thought, they’d basically been ripping off all their best bits from these guys, these French classical composers from the turn of the 20th century. And at the same time, I discovered Erik Satie’s Gymnopedies, via an album by the group Sky, remember Sky?

JUSTIN LEWIS

I do, my dad had one of their albums.

JONATHAN COE

My mum had one of their albums. I didn’t think much of it really, but in the middle of one side, there was this one tune, which was just fantastic and I thought, wow, one of the guys in this band is a really good composer. So I looked at the credits, and it was someone called Erik Satie, who apparently had written this piece 100 years before, but which still sounded incredibly modern.

JUSTIN LEWIS

I knew the ‘Gymnopedie No. 1’ because I was studying it for flute. Thinking about it, that might have been my introduction to French classical music. I think the Debussy sonata is meant to be the first prominent work for that specific combination of three instruments, flute, viola and harp – it’s not absolutely the first, but the first major work. A real breakthrough.

JONATHAN COE

Yeah, it’s just an absolute masterpiece. I mean, I have lots of big blind spots in music, I hardly listen to 19th century classical music at all, but from 1888, as soon as Satie uses those major seventh chords in those Gymnopedies… everything starts to make sense for me again, and then that led me into Poulenc and into Honegger and all those other French composers of that period. And it always makes perfect sense to me that Vaughan Williams studied with Ravel in France, because although there’s a kind of a deep-rooted Englishness in his music, through the folk tunes and so on. I also hear a kind of Ravel-like delicacy in a lot of his orchestrations. So I fell in love with Vaughan Williams’ music at that time as well, and have been listening to him constantly ever since.

—

JUSTIN LEWIS

Your next novel, Bournville, is out shortly, right?

JONATHAN COE

There’s almost nothing about music in that book! A bit of Herbert Howells and that’s it. No, actually – I tell a lie – there’s a huge section about Messiaen and his Quartet for the End of Time.

JUSTIN LEWIS

If you’re into music, you can’t help it!

JONATHAN COE

I can’t. It’s everywhere, isn’t it?

—-

Bournville was published by Penguin Books in November 2022.

Jonathan’s fifteenth novel, The Proof of My Innocence, was published by Viking in November 2024.

Jonathan’s website, with further details of all of his books, can be found at jonathancoewriter.com.

To hear some of his music, you can visit his bandcamp page: sparoad.bandcamp.com

You can follow Jonathan on Bluesky at @jonathancoe.bsky.social.

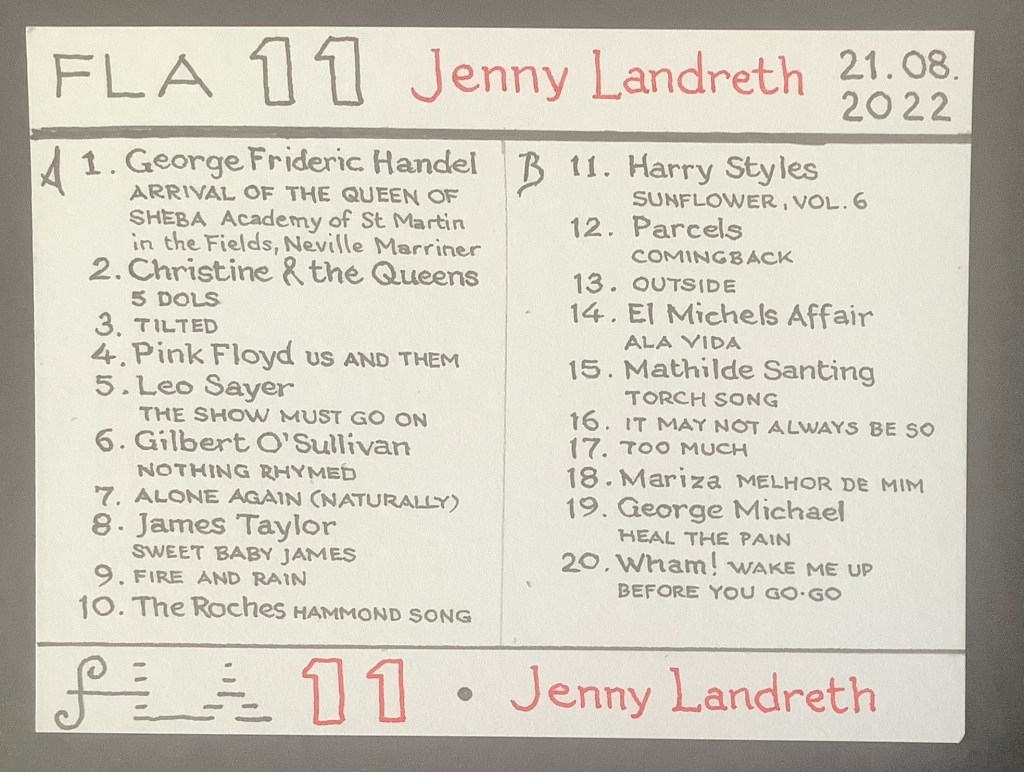

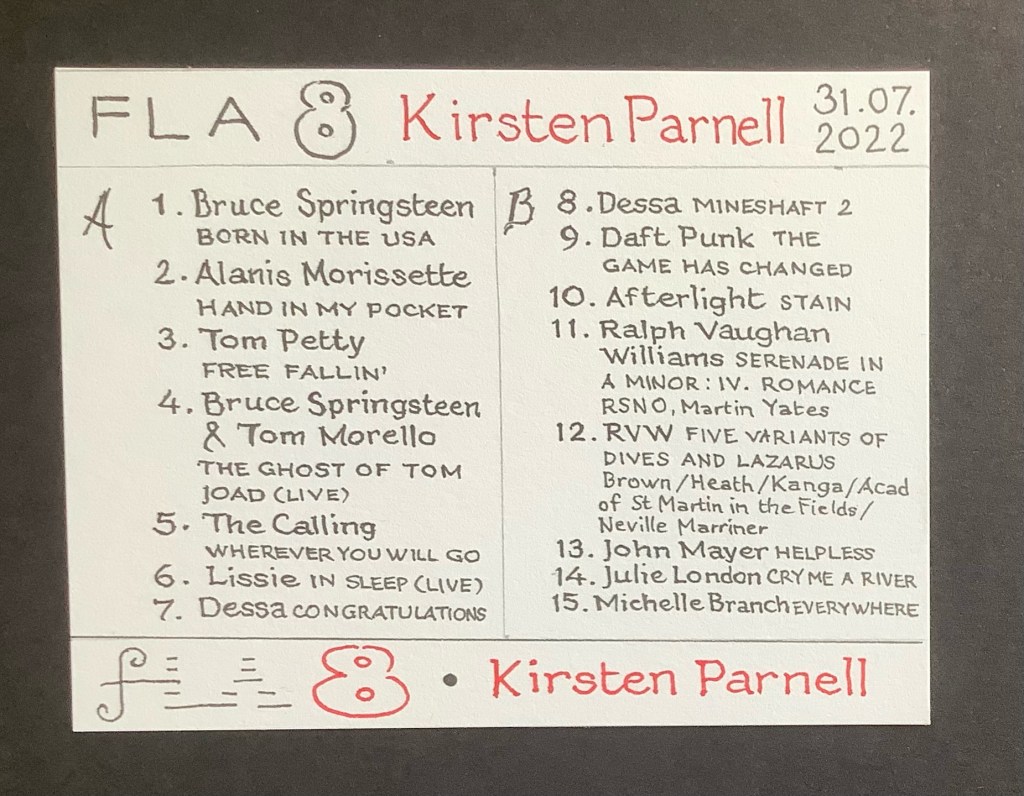

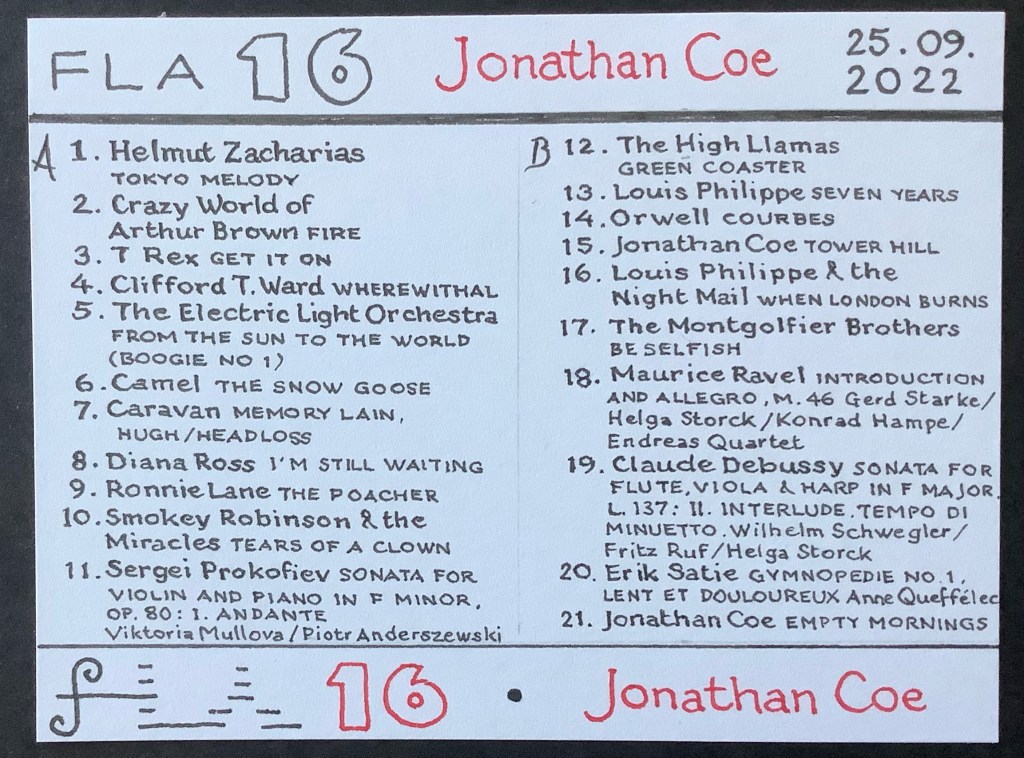

FLA PLAYLIST 16

Jonathan Coe

(For the time being, this site and project uses Spotify for the conversation playlists, but obviously I disapprove that Spotify doesn’t pay artists and composers properly, and other streaming platforms are available, as are sites to buy downloads and buy recordings. For consistency, you can also listen to the selections via YouTube (where available), and links are provided in each case, below.)

Track 1: HELMUT ZACHARIAS: ‘Tokyo Melody’: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZteHNQZcQQM

Track 2: CRAZY WORLD OF ARTHUR BROWN: ‘Fire’: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RLG1ys2CGcI

Track 3: T REX: ‘Get It On’: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FyzWDl0nz00

Track 4: CLIFFORD T. WARD: ‘Wherewithal’: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pBMGg6dNT90

Track 5: THE ELECTRIC LIGHT ORCHESTRA: ‘From the Sun to the World (Boogie No. 1)’: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wVGv-avRA64

Track 6: CAMEL: ‘The Snow Goose’: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cs0cJVEtxJo

Track 7: CARAVAN: ‘Memory Lain, Hugh/Headloss’: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-7ReI3YpEzs

Track 8: DIANA ROSS: ‘I’m Still Waiting’: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gTAZh4Sccsk

Track 9: RONNIE LANE: ‘The Poacher’: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hFvN1i8m4bU

Track 10: SMOKEY ROBINSON & THE MIRACLES: ‘The Tears of a Clown’: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4heHLbchPKk

Track 11: SERGEI PROKOFIEV: Sonata for Violin and Piano in F Minor, Op. 80: I. Andante

Viktoria Mullova, Piotr Anderszewski: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Pe76VJ1NsIk

Track 12: THE HIGH LLAMAS: ‘Green Coaster’: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=54XhZYSYv4c

Track 13: LOUIS PHILIPPE: ‘Seven Years’: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Tha_vQz_ZBA

Track 14: ORWELL: ‘Courbes’: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-0YxqCew8_Q

Track 15: JONATHAN COE: ‘Tower Hill’: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7e8AFPk2wp8

Track 16: LOUIS PHILIPPE & THE NIGHT MAIL: ‘When London Burns’: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=oQi4hpr8f2s

Track 17: THE MONTGOLFIER BROTHERS: ‘Be Selfish’: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zag2USOkcOA

Track 18: MAURICE RAVEL: ‘Introduction and Allegro’, M.46

Gerd Starke, Helga Storck, Konrad Hampe, Endreas Quartet

Track 19: CLAUDE DEBUSSY: Sonata for Flute, Viola and Harp in F Major, L. 137:

II. Interlude. Tempo di Minuetto

Wilhelm Schwegler, Fritz Ruf, Helga Storck:

Track 20: ERIK SATIE: Gymnopedie No. 1, Lent et douloureux

Anne Queffélec:

Track 21: JONATHAN COE: ‘Empty Mornings’