I firmly believe that the iPod Classic, introduced twenty years ago last month and scandalously now discontinued, is the finest invention of the 21st century, apart from obviously all the pioneering and lifesaving developments in medicine. For reasons that are best left to another post, I don’t want all my music on a phone, I don’t like being interrupted, so the Classic was the ideal format for storing a ton of music. And perhaps its greatest feature, apart from its portability, was its shuffle feature, very common on devices now, but not then.

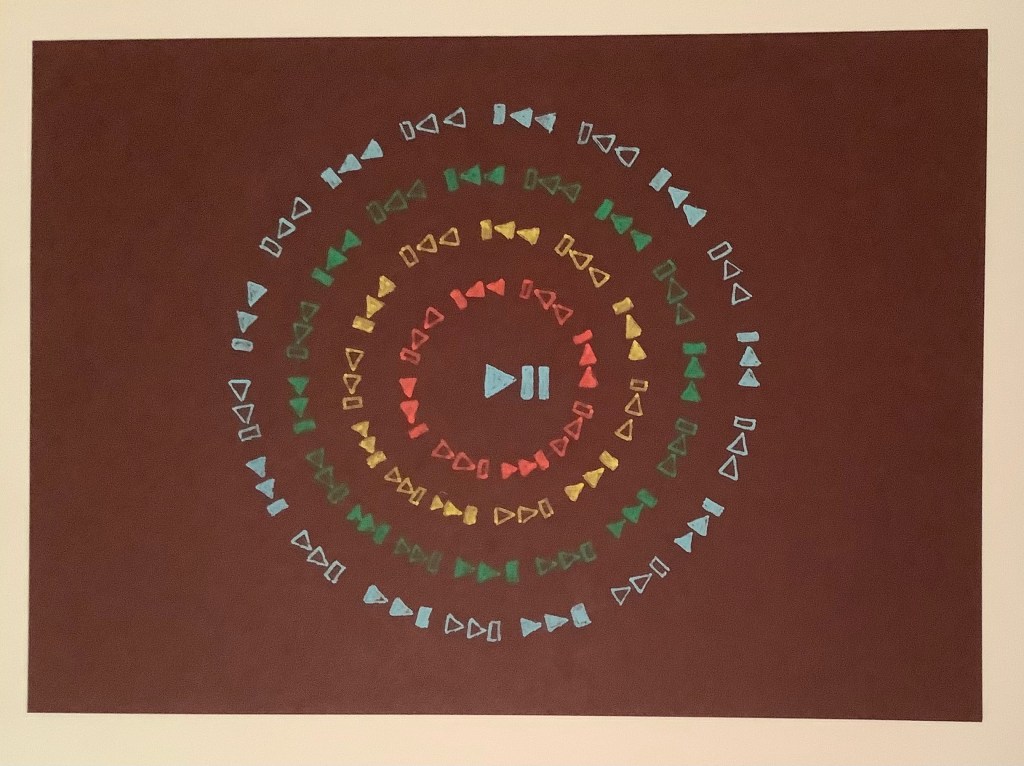

I have usually been just as interested in current music as for what I suppose what is now called ‘heritage music’, oldies and classics, and so the iPod was an ideal fit for me, and the shuffle function performed an ingenious, new way to listen to music. It was like having one’s own radio station, where your whole collection lived on top of each other, and would interrupt each other, in an endless stream of unexpected segues. The juxtapositions used to amuse me, but they could often be moving – suddenly you’d be whisked back to a family holiday or that friend you’ve lost touch with or that person you fell in love with, or even a more troubling incident that you’ve more or less worked through now. In that circle of randomised tracks lies the inventory of your life – your constantly evolving memories and your continually unfolding present day.

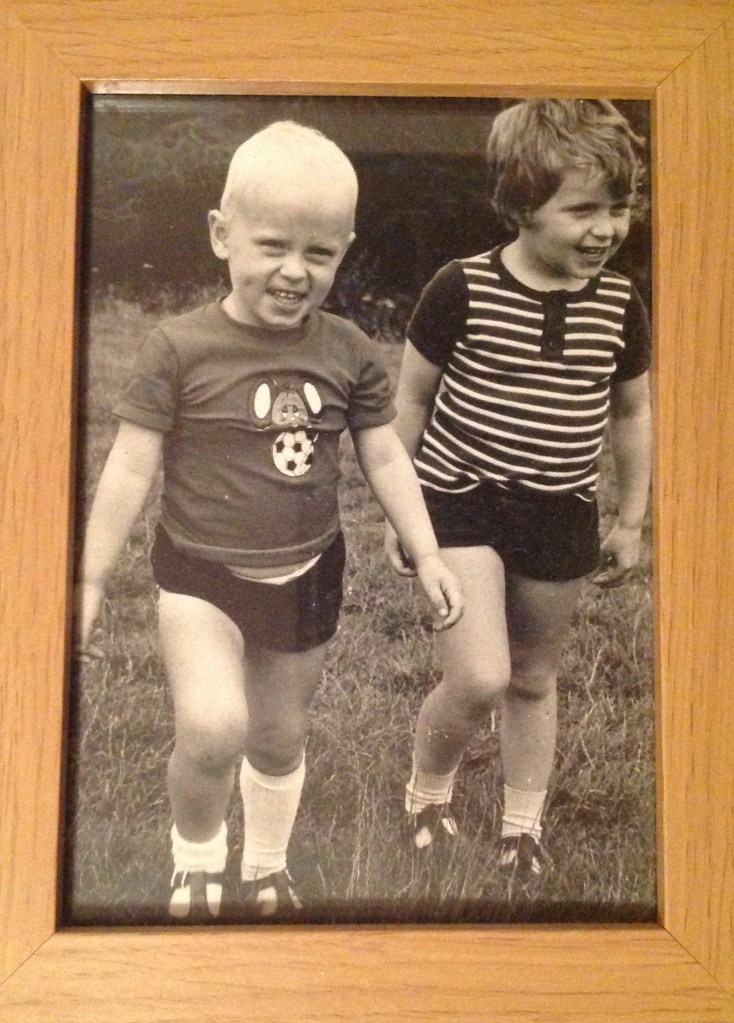

As with nearly everything, I was fashionably late to the iPod Classic – it was 2008 when my brother Jonathan bought me one as a Christmas present, my name engraved on the back with love. And it seemed a logical present, given how deeply music lay in our bones. We had a father who filled the house with music, music of all genres, and while he was critical of so much, the one thing he was, was eclectic. And so were we.

The first two singles that Jonathan ever bought, if I remember correctly, were Dennis Waterman’s Minder theme, ‘I Could Be So Good for You’, and David Bowie’s ‘Fashion’ – both purchased in late 1980, when both were in the top ten. I don’t know if he’d thank me for listing some of his early singles and LPs, but I think there’s something enlightening about the randomness of record buying, pre-internet. Because records could be bought on a whim, or the sign of an obsession, or just a passing enthusiasm, or even just ‘it was reduced in a sale’. Record collections are often a series of accidents rather than a careful curation of taste. And this was never more true than when you’re ten or eleven, and have yet to cave in to peer pressure. ‘Pass the Dutchie’, ‘Ebony and Ivory’ and the first Wham! album were all things he bought and soon lost interest in (though I quickly nabbed that last one for my own collection).

And then, before I did really, he became interested in the album rather than the single. Tin Drum by Japan was a constant sound in our house – particularly ‘Canton’ for some reason – and soon, as he became involved in the local surfing culture, his often much older friends would lend him albums. It’s hard to remember now which albums in our house were bought and which ones were borrowed, but – to give you an idea – Talking Heads, Sex Pistols, the Clash, the Beat, INXS (the latter long before they had any hits in Britain).

And AC/DC, who along with Pearl Jam were possibly his all-time favourite band. There was a period in the mid-1980s, when we were teenagers, when you knew when Jonathan was getting up for school. You’d hear the slow tolling bell heralding “Hells Bells” by AC/DC. It was like the thrilling alarm of doom at about 7.45. But then we had a noisy house. Three of us had loud stereos, my dad’s being the loudest of the lot. And then on a Sunday, as a family, we’d listen to the Top 40 when we had our evening meal, and would argue about the merits or otherwise of the current hit parade. It was my idea, but I’m grateful they indulged me.

Jonathan died ten years ago. The day before he died, I was sitting in his room, next to his bed. An iPod playlist had been set up, on shuffle, all the mellow favourites. And everything set off a memory. Stevie’s ‘Pastime Paradise’, the soundtrack to West Wales holidays in the late 70s. ‘Is This Love?’ by Bob Marley, which was on a tape of the Radio 1 Top 20 we played endlessly around the same time, before we got round to buying our own music. And then ‘Our House’ by Crosby Stills Nash & Young, a song of quiet contentment, and an unwittingly cruel track to hear in such a context – ‘Life used to be so hard.’ I can never hear it in the same way again, and a few months after he died, some TV ad for a DIY store did their own abysmal cover version, which managed what I thought no piece of music could possibly achieve: it made me laugh and cry at the same time.

In those days I was still living in south London, but for a variety of reasons – and that was one – I soon moved back to Wales. But I continued to visit London, often to housesit for friends who were still there.

In April 2014, I was housesitting in south-east London, not far from Peckham, and was visiting a friend in Crystal Palace. As ever, I travelled around everywhere – bus, train, tube, on foot – with the iPod Jonathan had given me. That night, I caught a taxi ‘home’ to where I was staying. The following day, to my horror, I couldn’t find the iPod. I suppose it feels strange to call it an heirloom, but it certainly felt like a prized possession given by someone who was no longer around.

I phoned every place I’d been the day before: the pub, all the shops, Transport for London, even the cab company whose driver had taken me ‘home’. But to no avail. God bless my amazing friends – above all, Alasdair and Becky – who crowdfunded to buy me a replacement iPod for my birthday a few weeks later. When they presented it to me – with probably thirty people in the room – it was one of those evenings I will never forget. My incredible friends. X

I probably used to be less judgemental about music than I am now. Maybe it comes with age, it’s not just that you accept that people have different tastes; it’s more that music is a soundtrack to your life, and that includes stuff you thought you barely noticed, even stuff you thought you hated, even stuff you actually hated. It’s all part of your life.

Early June 2014. Another housesit – different house, same area of south-east London, though. I went out to central London that Saturday, and in the evening met Alasdair and Becky and several other friends in Crystal Palace. We asked the restaurant to call me a cab, as the others prepared to get their buses and trains. On the way back, I answered a few texts, and the driver and I exchanged a few words, but little more than that. Until we were nearly ‘home’, about two streets from my destination.

‘I think I’ve driven you before,’ he said.

‘Oh really? It’s quite possible.’

One street away.

‘Are you Justin?’

‘Err, yes?’

(Bit worried now.)

We had arrived. He pulled over and stopped the car.

He opened and reached into the glove compartment, and then he turned to me.

‘Is this your iPod?’

——-

I.M.

Jonathan Lewis 1971–2011

Rebecca Taylor 1980–2014

Vivian Lewis 1938–1994

If you mourn the passing of anyone close to you, and especially if they died relatively young, that anniversary and the days leading up to it are likely to feel tense. While life has to go on, the tension between ‘carrying on regardless’ and ‘reflecting’ means there are a few dates in the calendar which one will always dread.

If you mourn the passing of anyone close to you, and especially if they died relatively young, that anniversary and the days leading up to it are likely to feel tense. While life has to go on, the tension between ‘carrying on regardless’ and ‘reflecting’ means there are a few dates in the calendar which one will always dread.