Additional artwork (c) Dotty Sutton

I never know what people are going to choose for FLA, and this is part of the joy of doing it. Even when I’ve known the guest for some time, as with this episode’s collaborator.

I met Gary Panton in the early summer of 2007, when we were working in the same office, compiling TV listings information. Subsequently, we both worked in publishing, though usually in different places. We shared a similar sense of humour, and so I’m so pleased to see that Gary’s career as a children’s author has taken off so well this year, 2025. His first book, The Notwitches, published in early 2025, has been warmly received by many younger readers. His flair for daft, surrealistic humour has been acclaimed by some grown-up critics too: The Times newspaper likened The Notwitches’ dialogue to that of Blackadder and Python, admiringly calling it ‘a triumph of nonsense’; The Scotsman summed it up as ‘a madcap adventure’ and also drew attention to the book’s ‘fun-filled illustrations’ by Dotty Sutton – as did the i Paper, who called the result ‘irresistibly fun’.

With August 2025 seeing the publication of Gary’s second Notwitches book, Prison Break, I spoke to him on Zoom in early July of that year, to discuss some of the music that has fired his imagination over the years. In the conversation that follows, we touch on the influence of music in popular cinema during the 1980s and early 1990s (during Gary’s formative years), what it’s like to be a fan of a band for many years, and ultimately talked about what everyone simply won’t shut up about during the summer months: Christmas music.

——

JUSTIN LEWIS:

What sort of music was playing in the Panton household in your early life?

GARY PANTON:

I can remember my dad had quite a big music collection, quite a lot of vinyl. He was into the sort of stuff that I guess would be called ‘dad rock’ now – Dire Straits, quite a lot of Bob Dylan. My mum, I don’t think was ever that into music, but – I was thinking about this earlier – she had this exercise cassette, that plays music and someone gives out instructions over the top of it.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

Oh yes, they were called ‘Shape Up and Dance’ albums, some of them.

GARY PANTON:

And this one came with a massive poster that she used to lay out on the floor, and you had to move all the furniture to make room for it. She’d play the cassette, and me and my sister would be a nuisance in the background while she did these exercises. But it was weirdly all mid-tempo-to-slow songs on this, which you wouldn’t really exercise to now.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

Everything’s a ‘running playlist’ now!

GARY PANTON:

I can remember it being quite Motown-y stuff, like Lionel Richie. I really remember the song ‘Being With You’ by Smokey Robinson being on there, and I loved that when I was quite young. So, I don’t really remember my mum having much actual music other than that, but I just always associate her musical taste with that tape.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

I wonder if it’s the Shape Up and Dance with Felicity Kendal album from 1981? Features soundalike covers.

GARY PANTON:

Having just listened to some of this on YouTube, there’s a very good chance it is this! Surprised to hear it’s covers, though very convincing covers.

[We couldn’t track down the accompanying poster, regrettably. Or maybe we did:]

JUSTIN LEWIS:

Dads seemed to control the stereo in those days. I think that’s changed. I’ve noticed a pattern just doing this series, where the music mums liked in the past was sometimes not taken very seriously.

GARY PANTON:

I do remember my mum telling me a couple of times that there’s loads of songs that she loves, but she wouldn’t really be able to tell you who they’re by. She doesn’t have a favourite artist, she just likes lots of things.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

My mum’s like that.

GARY PANTON:

Which is the complete opposite of how I am with music because if I like any song, I just immediately want to know who it’s by. I want to know all the information about it. When it was physical music, I’d want it in my actual collection.

—–

—

JUSTIN LEWIS:

You were born about ten years after me, and one thing that occurred to me: your earliest musical memories, in the 1980s, are associated probably more closely with visual accompaniment. I mean, I remember the ‘Bohemian Rhapsody’ video on Top of the Pops for weeks on end, but pop groups rarely made proper videos in the 70s. Whereas pop video in the 80s…

GARY PANTON:

I was definitely very attracted to songs that came with a good video. And when we got Sky TV, which I guess would have been in the early 90s, I suddenly had access to music channels: MTV and VH1. I used to watch them all the time – a lot of my music knowledge comes from that because when the video was playing, the year and the album title would come up on screen.

As a kid I used to particularly love any song that came with an animated music video. So things like ‘Sledgehammer’ by Peter Gabriel, ‘The Motown Song’ by Rod Stewart and the Temptations, ‘Club at the End of the Street’ by Elton John… and the ultimate one was ‘Opposites Attract’ by Paula Abdul.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

With that last one, I seem to remember you mentioning on Twitter, some years back now, that with ‘Opposites Attract’ they don’t ever seem to discuss that it’s a cat.

GARY PANTON:

The whole song is built around them listing their differences, but at no point do they mention the key difference – she’s a real-life woman and he’s an animated cat. In that sense, they have quite a big ‘opposite’ there, which is going to make the relationship very difficult.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

It’s kind of like: ‘Never mind the smoking, you’re a drawing.’

GARY PANTON:

‘You’re two-dimensional. This is not gonna work.’ I’ve always wondered if the song was written with the video in mind. Maybe it was originally just meant to be a duet between any two singers, in which case you wouldn’t mention one of them being a cat. But then the cat comes into it and neither of them ever acknowledge it.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

The album had been out for quite a while, before that was a single. Was it MC Skat Kat?

[After our conversation, I discovered Skat Kat was indeed in the video, but the vocals on the track itself were from The Wild Pair, ie Bruce DeShazer and Marvin Gunn, previously of the band Mazarati, and therefore also backing singers on ‘Kiss’ by Prince!]

GARY PANTON:

Yeah. I do still love that song. It’s on one of my playlists – it came on in the car the other day, and this very conversation we’re having happened between me and my wife. And it’s around that time [1990] that I started buying my own music.

—–

FIRST: ORIGINAL SOUNDTRACK: Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles (SBK, 1990)

Extract: Partners in Kryme, ‘Turtle Power’

GARY PANTON:

I was already right in the prime target market for Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles… or Teenage Mutant Hero Turtles as it was called here.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

Yes, it was like Top Cat becoming Boss Cat all those years. I’m going to be absolutely transparent here about Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles. I don’t think I have ever seen it – even when I was a student and it used to get shown on Going Live! every Saturday, that would be the twenty minutes when I’d go and shower or make breakfast. But with ‘Turtle Power’ – because I promise you that I really do try and listen to everything before we discuss the records – I was playing the soundtrack, and I assumed I knew ‘Turtle Power’. But when it came up, I had no memory of it sounding like this at all. My memory of it is some hybrid of [Bobby Brown’s] ‘On Our Own’ from Ghostbusters II, ‘What’s My Name’ by Snoop Doggy Dogg, ‘Do the Bartman’ [by The Simpsons] and bits of DJ Jazzy Jeff and the Fresh Prince. And yet this was number one for a whole month when I was working in record shops.

GARY PANTON:

It’s funny how the songs you just listed are basically the other songs I was considering for this. Definitely ‘On Our Own’, which I bought as a single. Anything that was connected to a film or a TV series. And I was obsessed with the Turtles. I would have pestered my parents for the T-shirts and the action figures, so obviously when I started to get into music, it was, like, of course I have to buy this soundtrack when it comes out.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

And the film which I haven’t seen either, but it was directed by Steve Barron who’d done Electric Dreams but also the ‘Take On Me’ video for A-ha.

I’m sure MC Hammer was a draw as well because he’s on this soundtrack, as is Ya Kid K, who’d been with Technotronic.

GARY PANTON:

MC Hammer was definitely a draw for me at that time. I guess in a way, if you were a kid, you could feel like you were listening to serious hip hop: ‘I’m liking some real music here, this isn’t just kids’ music.’ The film’s a bit like that as well because it has a much darker, more brooding tone about it than the cartoon series. Which is quite clever because as a kid, you feel like you’re watching something that’s a bit grown-up.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

Which is kind of what the Tim Burton Batman film had done the previous year [1989].

GARY PANTON:

Yes, it’s very, very along those lines.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

So did you have this sort of visual appreciation of music at this time, that it was about the video or film as much as the record? Because I know soundtracks are important to you… Back to the Future, Ghostbusters, and you also mentioned Beverly Hills Cop.

GARY PANTON:

Yes, a lot of the early albums I bought were these 80s and 90s soundtracks. Even now, I love all that stuff. It takes me back. It’s a nostalgic thing, but it also takes me back to something that I don’t think really exists anymore. I don’t think movie soundtracks are as much of a thing now.

Another thing you don’t really get in films now, and ‘Turtle Power’ is just one example of this, is a rap over the end credits that basically summarises the whole plot of the film. I think that peaked with Will Smith doing it for Men in Black and Wild Wild West, and maybe then people started to think it was a bit cheesy and stopped doing it, but it coincided with that emergence of hip hop into the mainstream, and so every film thought it had to have a rap in it.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

As you mentioned Will Smith, doesn’t The Fresh Prince of Bel-Air also explain the premise of the show over the opening titles?

GARY PANTON:

It does, yes.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

So when did you last put on the Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles soundtrack?

GARY PANTON:

I listened to the ‘Turtle Power’ song literally just before we started, but I haven’t listened to the full soundtrack in a long time. I don’t think it’s available in full on streaming platforms. There’s a song on there called ‘9.95’ [by Spunkadelic, written by Dan Hartman and Charlie Midnight, also writers of James Brown’s ‘Living in America’], which I maintain is one of my favourite songs ever, and you just can’t get it anywhere. There might be a version on YouTube, but it’s not on any streaming platforms. I tried to find it on Apple Music and there’s a Chinese cover version of it (I think, as the group are from Hong Kong), but the original is really hard to find. It’s the same with the Ghostbusters soundtrack, I tried to listen to that recently, and there’s just a lot of songs that aren’t available to listen to on platforms anymore. I think that’s where owning a CD really still has a lot of value, because those songs are always yours to listen to and you’re not reliant on platforms keeping the music up there for you.

Spunkadelic: ‘9.95’

JUSTIN LEWIS:

A lot of soundtracks now are existing hits, but in those days, soundtracks would have songs written for the film, or songs donated by artists which wouldn’t fit on their albums. But they’d also have, usually near the end of Side 2, incidental music from the film.

GARY PANTON:

I absolutely love the main theme on the Back to the Future soundtrack. ‘Axel F’ from Beverly Hills Cop was a great one too. I think I also had the Crocodile Dundee soundtrack, and that had a cracking score. And one thing about all this is they’ve started bringing some of this stuff back. I watched the new Beverly Hills Cop film quite recently, and it basically has all the songs from the soundtracks of the first couple of films. Same with The Karate Kid – there’s the Cobra Kai series on Netflix and particularly in the first season of that, they play a lot of the music from the original film. Same with Ghostbusters – there’s a big nostalgic feel to all this stuff.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

I guess it stands to reason that the people running film studios are probably somewhere between your age and mine, and so they’re saying, ‘Let’s go back and reboot things that I liked when I was young.’

—-

JUSTIN LEWIS:

Tell me about The Notwitches, then, which is your first book for children.

GARY PANTON:

The Notwitches is a story about a little girl called Melanda Notwitch, who lives with her three aunts, who are just the most horrible people you’ll ever meet. She’s basically trapped with them, so she has a pretty terrible life, until there’s a knock at the door from a girl who claims she’s a witch. The witch promises Melanda that she knows a magic spell that can help her out of her predicament, but to complete the spell, they need one special magic ingredient. So they go off on a little quest to find this ingredient.

Obviously, they have to confront the aunts along the way, but they also meet lots of weird characters, goblins and monsters. And there’s a cat that can talk, but it can only say three words.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

I really really enjoyed reading it.

GARY PANTON:

Thank you.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

It’s in that grand tradition of children’s literature in being about outlandish and grotesque and humorous storytelling. Was that the kind of book you enjoyed reading as a kid yourself? Also, it feels quite filmic.

GARY PANTON:

I think Roald Dahl’s probably the obvious one. I was obsessed with Roald Dahl, particularly The Witches. I now read quite a lot of horror and ghost stories for adults but I still think the bit in The Witches with the little girl trapped in the painting is probably one of the scariest things I’ve ever read. So I loved anything that was a bit scary. But I was also into anything that was funny and silly. I used to love reading the Asterix books, Dr Seuss… just anything that would make me laugh. I think the influences for The Notwitches are a combination of books I read, TV series, funny films. It’s interesting you say it’s filmic, because I always wanted the book to be quite visual. It was always important to me that we’d be able to do things like play around with different fonts, and have the art really integrated into the story.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

I don’t have children, and my nephew is now sixteen so there’s no reason for me to seek it out naturally, but – and I don’t know how common this effect is in children’s literature now – I enjoyed how, with each double page, there’d be some kind of illustrative effect, even if it was just a cobweb in the corner, your illustrator Dotty Sutton would contribute as well. You’re not just reading text, you’re reading images as well.

GARY PANTON:

That was definitely what I wanted from the book. When I first spoke to the publisher, Chicken House, I told them that I really wanted this to be a visual experience, and I wanted there to be something that makes you laugh on every page. I need to give a shout-out to Dotty because she’s done such an incredibly good job. She’s one of the best illustrators around, and it feels a real privilege to have been able to work with such a talent on my very first book.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

How did you make contact with her?

GARY PANTON:

I said to the publisher, I really want this to feel anarchic and silly. Maybe 10% sweet and innocent, but 90% energetic and over-the-top and laugh-out-loud funny. I basically wanted the visual equivalent of the humour of someone like Rik Mayall. We looked at a few different illustrators and they were all really good, but the thing that stood out with Dotty’s work was that it just had that humour. You can tell she’s a really funny person who understands comedy. I didn’t give her much instruction at all, she just knew how to make the art funny.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

So did you send her the text for her to illustrate around it?

GARY PANTON:

Basically, yes. There were maybe only two or three places where I had specific things that I asked for. Most of the rest of it just came out of Dotty’s own head, even down to how the characters look. Some of the characters don’t get described in much detail in the text, so she’s just come up with a lot of that herself.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

And when she came back with the illustrations, did it make you tweak the text at all, or made you rethink anything?

GARY PANTON:

That happened a couple of times. In Book 2, which is coming out shortly, one of the new villains has a quiver of arrows on his back. That wasn’t mentioned anywhere in the text, but when I got that sketch back from Dotty, I just found it so funny that he wears that for no reason. So I tweaked the text to mention that in the description of him. But for the most part, when I see Dotty’s art, I don’t want her to change anything. It goes straight into the book as it is.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

Not to be too restrictive about it, but did you have a readership age group vaguely in mind?

GARY PANTON:

Not at all. You know what? I wouldn’t even really say I wrote it specifically as a children’s book. I just wrote what I wanted to write. I wanted to write something funny and quite surreal, and for it to be illustrated, and the silliness of the humour makes it very child-friendly – so all of those things make it a children’s book. But I don’t particularly write with kids in mind or adults in mind. I just write what I find is funny. When I was first looking for an agent and I was showing it around, a couple of them actually said that they thought it was something adults would like to read. But the problem is that would put it in a genre that doesn’t really exist. Illustrated comedy stories for adults aren’t really a thing in literature, at least not in a big way.

Another big influence on The Notwitches was TV comedy, especially The Mighty Boosh. Originally I was trying to come up with a way for Melanda, as the lead character, to end up in a really weird, surreal world. But when you try to do that, you spend four or five chapters just having her finding a portal, going into a portal, getting sucked into this other world… and then you need to find a way for her to get back out of it. And then one night I was watching a few episodes of The Mighty Boosh, and I realised that those characters are already in this really ridiculous, surreal world, and it never needs to be explained. People just go with it. So I never really say in The Notwitches what this world is, or why it’s so weird, but kids just get it straight away.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

With a second Notwitches book, Prison Break, out imminently, did you write the first one realising that it might have legs and you might be able to write a sequel or even a series? Or did your publisher encourage you?

GARY PANTON:

A bit of both really. The first book works as a self-contained story, but it finishes with an open-ended suggestion that there’s another adventure coming, and that suggestion was always there from the very first draft. And I always had in mind that, if there was a second story, it would be about Melanda trying to find her parents. So the publisher made it a two-book deal with the agreement that Book 2 would be a second Notwitches book rather than a different story. And they delayed the publication of the first one to give me time to write the second one, so that I would be able to release them both quite quickly. Because obviously when you’re writing kids’ books, children are going to grow up quickly. And if I wait two or three years between books, the readers of the first book will have moved on to something else and they won’t be into it anymore. So speed is quite important with a children’s series.

I found writing the second book a lot of fun because I love re-visiting those characters. In this one, Melanda is trying to break her parents out of a prison for witches, but in order to do that she has to get into the prison first. So the first half of the story is about her trying to get into the prison, and the second half is about her trying to get back out of it. It gave me a lot of opportunity to riff on various prison movie cliches along the way, which I loved.

It’s a really interesting experience writing a sequel. I always thought it would be easier because you’ve established the world and its rules, but actually that’s what makes it harder because you have to stick to those rules and can’t just make it up as you go along in the same way that you did with Book 1.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

In the acknowledgements for the first Notwitches book, I noticed you said you’d originally taken this idea to a writing group. So what were you writing before that?

GARY PANTON:

I’ve written all sorts of things over the years. I started out as a football journalist for a while. That was when I was a student. I got paid £20 to go to Scottish Premier League football matches, and I used to sit and count shots on target, shots off target, all that stuff, so that they had the stats at the end of the game. And I’d write the little short match reports that would be used in Match magazine, if anyone remembers those. I also did a little bit of live music journalism for the Sunday Mail. My main memory of that is that they refused to give me any sort of press pass, which meant a couple of times I turned up to gigs and the people at the venue didn’t believe who I was. They thought I was just someone trying to blag my way in, which always made it really awkward. I also did a few celebrity interviews over the years, lots of writing for magazines, and I worked in TV listings for a while too.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

Which is how we met, working together!

GARY PANTON:

And then I ended up working in publishing, and through that I started doing a little bit of freelance children’s writing, which was mainly nonfiction, things like picture books, lift-the-flap books for preschool age. A little bit of activity stuff, books for The Beano and Hey Duggee, and that kind of thing. I still do freelance writing on Hey Duggee books, and also Bluey books. I did some Danger Mouse stuff as well when the series made a comeback a few years ago.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

It’s really weird to interview your friends and discover they’re working on things you didn’t know about!

GARY PANTON:

But I’d always really wanted to do my own thing. The thing is, when you’re writing for a brand, you have to follow their rules pretty tightly. You have to be respectful to other people’s characters. And I increasingly really wanted to create something of my own, that I could push a bit further. Something I could make a bit more disgusting and revolting and over-the-top – all that sort of stuff that I find funny.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

It sounds like you’ve had some very good write-ups for the book. You’ve done lots of school events for kids, is that right?

GARY PANTON:

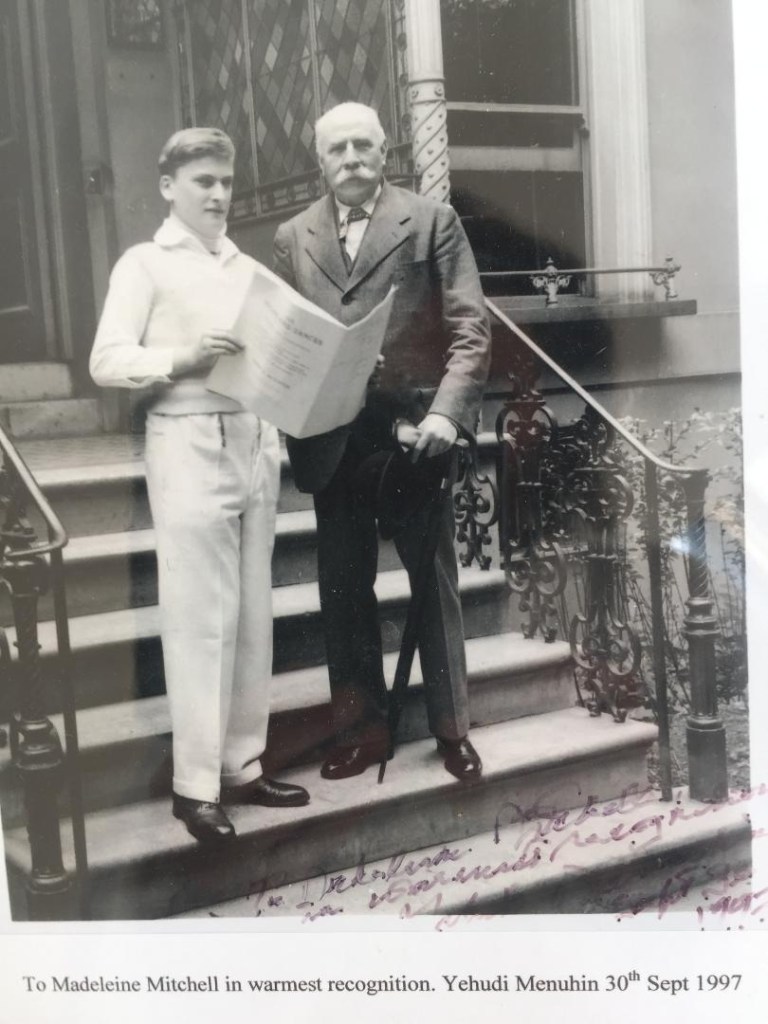

Yeah, me and Dotty have been going around schools doing little shows and signings. We did the Borders Book Festival a couple of weeks ago, which was an amazing experience. It’s actually fairly rare for an author and illustrator to even meet, let alone do these things together, so it’s been really good that the two of us have formed this little partnership. Hopefully that will continue. I was reading an Amazon review of the book where someone described it as an author-illustrator partnership that reminded them of Roald Dahl and Quentin Blake and that was really the best compliment I think I could ever receive.

But to go back to your previous question about the writing group, working in children’s media definitely helped me with writing the book. You pick up so many little hints and tips about what kind of characters are going to be successful. And taking the Notwitches idea to that writers’ group was really good for me because I sometimes find writing with no deadline can be a bit of a struggle. With that group, we would meet up every couple of weeks and read each other’s work, and then we’d all discuss it together. Everyone was so nice that there wasn’t that much criticism, so I don’t know if creatively it helped that much, but it definitely helped from the point of view of getting me to actually sit and write a thing.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

I think that’s half the battle, though. I honestly do. If you’ve got a deadline.

GARY PANTON:

It must have been eight or nine years ago that I was in that group and first started writing what became The Notwitches. I abandoned it for a while after that, but during COVID I decided to give it a proper go because I was sitting at home a lot, and I thought, I might as well try to finish it. It was a struggle at times but I’ve learned to just keep writing until the ending comes to me. Once I get to that point I can always go back and edit the earlier bits so that they work with the ending. I don’t plan any of the stories that I write, because I find that when I try to plan, nothing comes to me. Whereas if I just write and keep going, the ideas will come. I don’t know if you’ve read On Writing by Stephen King…

JUSTIN LEWIS:

I have – although not for a while.

GARY PANTON:

I found that really useful. He says: don’t worry what the plot is, or what the themes are, or the meaning. Just write and see what comes out – and that’s very much what I decided to do. I think you’ve got to be finding out the story as you go along. It’s like reading someone else’s book or watching a film and not knowing what’s coming next – I don’t usually know what’s coming next when I write, but I have the power to control it, which is a brilliant feeling to have.

—–

LAST: DEACON BLUE: The Great Western Road (Cooking Vinyl, 2025)

Extract: ‘People Come First’

JUSTIN LEWIS:

Obviously I knew Deacon Blue were still going and I knew they were still touring, and obviously we’re having this conversation only about ten days after the death of their keyboard player, James Prime. But they’ve been together for 40 years, and I hadn’t quite realised that they’ve made all these new albums especially over the past ten years.

GARY PANTON:

It’s quite hard now to know the last thing you either bought or listened to, because you’ve just got everything coming at you, but actually this was the last physical album I bought. Because I otherwise never buy physical albums anymore – I stream my music like everyone else. But I used to be really into collecting music. And the one concession I made when I left physical music behind was to carry on collecting Deacon Blue’s music. I have everything they’ve done – bootlegs, all the albums, all the singles, everything Ricky Ross has ever done as a solo artist, which is seven or eight albums. I’ve been to see them live more times than I can remember. And with this new album, although I’ve streamed it loads of times, I’ve not even taken the cellophane off the physical CD, because I don’t have a CD player now. But it’s just important for me to have it in that collection.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

So when did you first get into them, then?

GARY PANTON:

I probably didn’t discover them until they actually broke up, which was around ‘94.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

Yes, there was a greatest hits album at that time, called Our Town. And I’d known their first two albums quite well [Raintown, When the World Knows Your Name] but I didn’t really know the ones after that.

GARY PANTON:

In a lot of ways, I’m too young for Deacon Blue. When I go to the shows, I’m generally one of the youngest adults there. The audience tends to be people older than me and their kids, but I’m the generation in between. For a lot of people, Deacon Blue were their ‘student band’ in the 80s, but I’m about ten years too young for that. But yeah, that ‘greatest hits’ album you mentioned…

JUSTIN LEWIS:

That was your way in?

GARY PANTON:

Yeah, I played that a lot. Probably bought that before I knew they’d split up. But then, I often like music about 10 years after it’s been popular. It’s the same with Britpop – I was never into it in the 90s, even though I was a teenager at the time and I was probably right in the middle of the target market for it. Whereas now I actually quite like a lot of it. I don’t know what it is – it’s maybe similar to the movie thing in that it taps into my love of nostalgia … I like my music to be old!

In the late 90s, a few years after Deacon Blue split up, I was at uni in Stirling, and I started buying up their old stuff in the local record shops: second hand singles, previous albums. And then in 2001, they got back together, and I’ve been going to their gigs pretty regularly since then. They’re the band I always come back to, the one I listen to the most. The sound has changed quite a lot over the years, since the days of ‘Real Gone Kid’ and ‘Fergus Sings the Blues’. They’re not going to do that kind of thing again, I don’t think. But I think the new songs still do have quite a similar sound to Raintown, which was the first album.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

Raintown seems to be the one that everyone agrees on as the best one, or do you think there’s a better one?

GARY PANTON:

I would say so. I mean, it’s weird – Raintown didn’t really have any hit singles. Most of the hits were from the second album, When the World Knows Your Name – that’s got ‘Real Gone Kid’, ‘Wages Day’, ‘Fergus Sings the Blues’, the more uptempo poppy stuff. But now, if you watch them live, the ones that get the warmest reception are the Raintown ones, especially ‘Dignity’ obviously.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

Of course, and that did nothing when it first came out. Number one hundred and something! Eventually got in the top 20 when the greatest hits came out, but you still think of it as being much bigger, don’t you?

GARY PANTON:

Yeah, I believe their most successful chart single was the cover of Bacharach and David’s ‘I’ll Never Fall in Love Again’. Which I think got to number two.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

Behind Bombalurina!

GARY PANTON:

For a band who I generally think of as writing all their own stuff, it’s amazing that the biggest single was a cover.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

Although I think the reason for that is Deacon Blue are a good example of an ‘albums band’ and it was never on an album at the time, it was a stand-alone single EP. But it is interesting how a lot of people, when they first get into a band or like them belatedly, buy the greatest hits and decide that’s enough for them. Whereas you presumably heard something in those hits where you thought, I want to investigate more of this.

GARY PANTON:

Yeah, as someone who often got into bands after they were popular, a lot of the music that I’m into came through hearing greatest hits albums and then wanting more.

I think with Deacon Blue, with the new stuff, they’ve definitely matured a lot in their sound. But I would say there’s a sort of unique Deacon Blue sound – country meets blue-eyed soul meets what seems to be a very Scotland-specific yearning for better times. Quite similar to Del Amitri, who I also like.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

Did you know Justin Currie has a memoir coming out shortly? [The Tremolo Diaries, published by New Modern Books on 28 August 2025]

GARY PANTON:

Oh I’ll be up for that. One of me and my wife’s first dates was a Justin Currie concert.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

Oh how fantastic.

GARY PANTON:

I really love Justin Currie’s solo material in particular. In his solo shows he does a lot of the Del Amitri stuff, but just acoustically and on his own. Love love love Justin Currie.

Something I’ve just remembered is that my parents had an album of ‘the greatest Scottish hits’, and that had ‘Somewhere in my Heart’ by Aztec Camera’ – another favourite band – on there, and ‘Always the Last to Know’ by Del Amitri. There was probably some Deacon Blue on there too. I don’t think I was ever specifically liking music because it was Scottish, but I just seemed to gravitate towards a lot of these bands.

I have seen Roddy Frame once, I guess it must have been about 15 years ago. He actually did play ‘Somewhere in my Heart’ when I saw him. It was just him on his own in one of the West End Theatres in London, which was quite an unusual venue. But yeah, it was great.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

I was going to ask if the Scottish connection was important with these bands, because you’re from… is it Perth?

GARY PANTON:

I’m from Perth, yeah. Del Amitri are from Glasgow. Deacon Blue are basically from Glasgow, although Ricky Ross is from Dundee.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

Is there a famous band from Perth? I’m trying to think.

GARY PANTON:

There’s the Average White Band’s singer Alan Gorrie.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

That’s a good one!

GARY PANTON:

And also, Fiction Factory, who did ‘Feels Like Heaven’. That’s basically it as far as I know.

—–

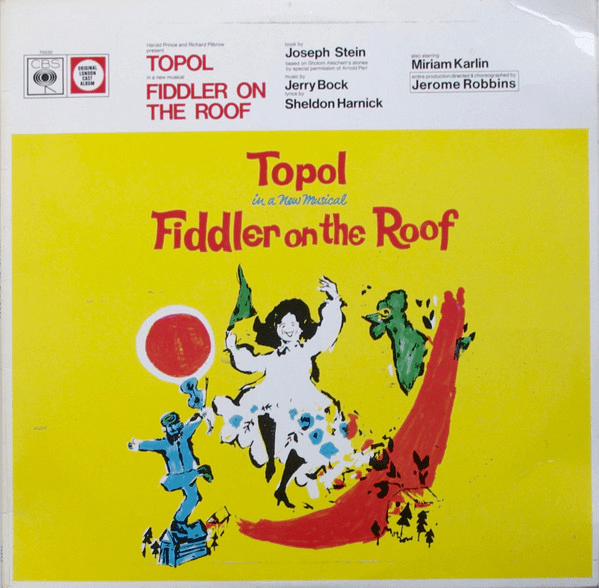

ANYTHING: VARIOUS ARTISTS: It’s Christmas (EMI, compilation, 1992)

Extract: Cliff Richard: ‘Mistletoe and Wine’

JUSTIN LEWIS:

We’re recording this on the first of July, by the way. This is a Christmas hits compilation from 1992, which I remember well because I was working at HMV as a Christmas temp (and went on to be full-time there for a while). Now – why have you chosen this?

GARY PANTON:

I mean, to give it a bit of context, I’m a massive Christmas fan.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

You’ve got all its records. All its posters, everything.

GARY PANTON:

Yeah. I’m trying to collect everything Christmas ever did.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

You’re like that bloke in the papers who has Christmas dinner every day!

GARY PANTON:

I’m not a religious person at all. But the cultural side of Christmas is something I just love: Christmas movies, Christmas books, Christmas food, going to Christmas markets. All of that stuff, so I think Christmas music obviously goes hand in hand with all of that. I think this compilation was one that my parents had, and I remember me and my sister just playing it all the time. It’s kind of ‘ground zero’ in terms of Christmas collections because it’s before a lot of the other stuff has taken off. It’s a lot more common now for artists to bring out Christmas songs, but these feel like the original Christmas pop hits to me.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

It’s a very interesting selection. It’s before the Pogues were on all Christmas compilations ever. And it’s pre-‘All I Want for Christmas is You’ so there’s no Mariah. But the big selling point for me on this one is Kate Bush’s ‘December Will Be Magic Again’, which is not even on streaming as we speak.

GARY PANTON:

I think this was like my introduction to the idea of Christmas songs as being one body of work. You keep coming back to them every year, unlike any other music. There’s a specific time of year when you listen to these precise songs, and it’s like a genre of its own, even though it contains completely different genres. I would never listen to these outside Christmas, which actually can be a problem because I’ve got so much of this stuff on my Apple music account that if I ever have it play random favourites, it’ll throw things up like ‘Fairytale of New York’ in July, which I don’t want to hear. I want to keep it special for Christmas.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

So you don’t occasionally try and see if it works at another time of year? Because I have a Slade compilation on my iPod, and when I play it from time to time, I do not skip ‘Merry Xmas Everybody’. Because to me, for a lot of the year, it doesn’t sound like a Christmas record, it sounds evergreen.

And at Live Aid, and we’re speaking in the run-up to the 40th anniversary, the Wembley side of the concert ended with a group rendition of ‘Do They Know It’s Christmas?’ In July. And in fact, that Band Aid single nearly got back in the top 100 after that concert.

GARY PANTON:

One thing I love about Christmas records is there are songs that really have nothing to do with Christmas, but as long as they’re marketed in the right way, everyone just happily accepts them as being festive. Two of my favourites are East 17’s ‘Stay Another Day’, and ‘Never Had a Dream Come True’ by S Club 7, both of which are only Christmas songs, really, because they wear warm jackets in the videos.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

And they’re in the charts at Christmas. Or they overdub sleigh bells on to the backing.

GARY PANTON:

Even ‘The Power of Love’ by Frankie Goes to Hollywood – I’m not sure what’s Christmassy about that.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

The video, really, I think. So at what point do you bid farewell to Christmas music? Do you do as the radio does and stop on Boxing Day, or do you keep going till Twelfth Night?

GARY PANTON:

I have quite a long period of Christmas music, but it does basically stop on Boxing Day. I’ll introduce it in the last week of November, so that I can get a good four or five weeks out of it.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

So, with this compilation, if you had to choose one or two from it, what would you go for?

GARY PANTON:

You know what? You might hate this, but I quite like a bit of ‘Mistletoe and Wine’, and I quite like Shakin’ Stevens’ ‘Merry Christmas Everyone’. My general feeling is that Christmas is the great leveller for music, there’s not really any room for snobbery. I mean, if you look at this album, there’s Lennon and McCartney – both have got songs on here – but there’s Shakin’ Stevens too. At Christmas, it doesn’t really matter who these people are. They’re all just bunged together into one great big mix.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

So does that mean when you’re listening to this, are you thinking of the artists particularly or just thinking of it as being a particular mood?

GARY PANTON:

I’m not that fussed about who the artist is. I mean, for most of the year I can’t bear Cliff Richard, so I guess it’s definitely that Christmas association with ‘Mistletoe and Wine’ that turns it into a regular listen for me. I draw the line at ‘Saviour’s Day’, though.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

I often think with Cliff, he’s like Elvis and Diana Ross in that some of his records are great, and some of them are terrible but he seems to have no quality control at all. But do you think, as a whole, the Christmas pop songs have become the new Christmas carols? Because you don’t really hear Christmas carols so much now unless you actually hear the Nine Lessons and Carols or go to church.

GARY PANTON:

No, I mean, I really like Christmas carols. I really like brass bands at Christmas time as well. I love all that stuff.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

On the subject of playing Christmas records out of season: when Danny Baker used to present Morning Edition, the daily breakfast show on BBC Radio 5 (before it became Radio Five Live), there was one morning [25 May 1992] and it was a bank holiday and he was just playing records under the banner of ‘What if rock’n’roll had never been invented’. And he proceeded to play, on a warm early summer’s morning, with no announcement, no wink, nothing, the Ronettes’ ‘Sleigh Ride’, from off A Christmas Gift for You. And it sounded absolutely amazing. Sometimes these things work in any context, against the odds.

——

Gary Panton’s The Notwitches is available now as a paperback and ebook from Chicken House Books. The second book in the series, The Notwitches: Prison Break is published in the same formats on 14 August 2025.

You can order Gary’s books through this link to a variety of outlets: https://garypanton.co.uk/books/

Gary and Dotty will be doing book-signings and draw-alongs at the following Waterstones stores in Scotland:

- Waterstones Perth, Saturday 16 August, 11am

- Waterstones St Andrews, Saturday 23 August, 11am

- Waterstones Edinburgh Fort Kinnaird, Saturday 6 September, 12pm

Keep an eye on Gary’s social media for other events that are yet to be announced:

Bluesky: @garypanton.co.uk

Instagram: @garypanton

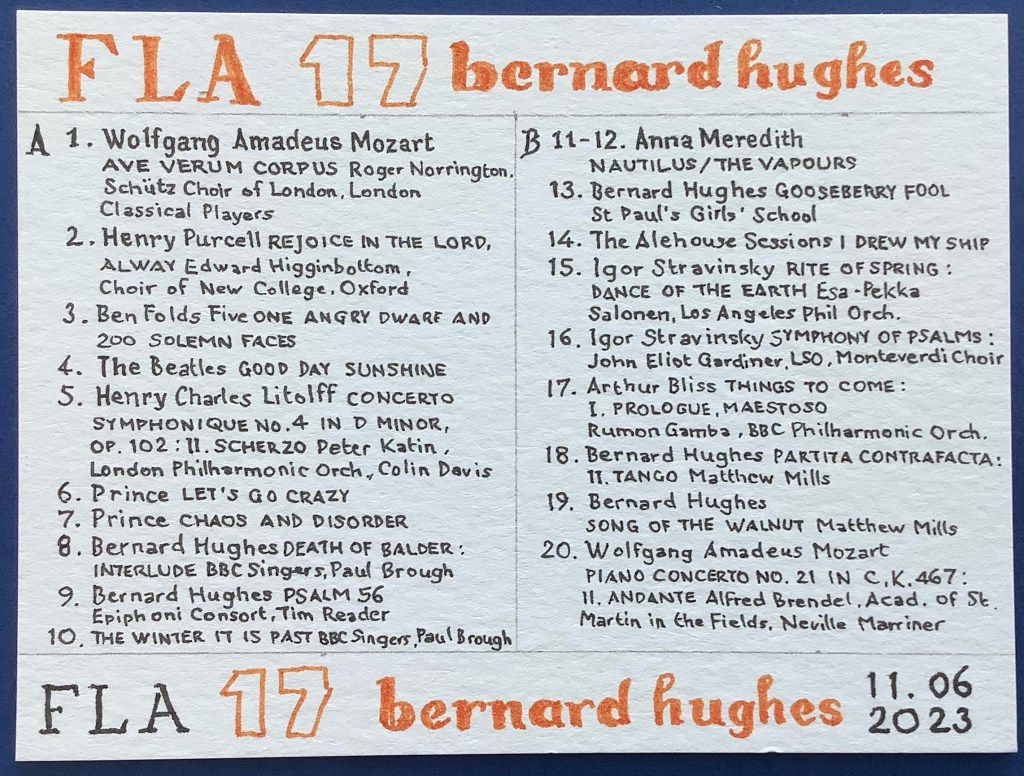

FLA 26 PLAYLIST:

Gary Panton

(For the time being, this site and project uses Spotify for the conversation playlists, but obviously I disapprove that Spotify doesn’t pay artists and composers properly, and other streaming platforms are available, as are sites to buy downloads and buy recordings. For consistency, you can also listen to the selections via YouTube (where available), and links are provided in each case, below.)

Thanks to Tune My Music, you can also transfer this playlist to the platform or site of your choice by using this link: https://www.tunemymusic.com/share/BdxXrgoAQI

Track 1:

SMOKEY ROBINSON: ‘Being With You’:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KTC5NYSBhts&list=RDKTC5NYSBhts&start_radio=1

Track 2:

PAULA ABDUL WITH THE WILD PAIR: ‘Opposites Attract’:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xweiQukBM_k&list=RDxweiQukBM_k&start_radio=1

Track 3:

PARTNERS IN KRYME: ‘Turtle Power’:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uxHWm_bGScY&list=RDuxHWm_bGScY&start_radio=1

Track 4:

HI TEK 3 FEATURING YA KID K: ‘Spin That Wheel’:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SrOVoplyjCI&list=RDSrOVoplyjCI&start_radio=1

Track 5:

HAROLD FALTERMEYER: ‘Axel F’:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Qx2gvHjNhQ0&list=RDQx2gvHjNhQ0&start_radio=1

Track 6:

THE OUTATIME ORCHESTRA: ‘Back to the Future Overture’:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=w8ONn5GdwTs&list=RDw8ONn5GdwTs&start_radio=1

Track 7:

PETER BEST: ‘Theme from Crocodile Dundee’:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-G8Jea83AVQ&list=RD-G8Jea83AVQ&start_radio=1

Track 8:

WILL SMITH: ‘Wild Wild West’:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_zXKtfKnfT8&list=RD_zXKtfKnfT8&start_radio=1

Track 9:

DEACON BLUE: ‘People Come First’:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=iaYoU5lLMK0&list=RDiaYoU5lLMK0&start_radio=1

Track 10:

DEACON BLUE: ‘Dignity’:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=I1g32-9-OG8&list=RDI1g32-9-OG8&start_radio=1

Track 11:

JUSTIN CURRIE: ‘My Soul is Stolen’:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Cmf5DTypcZg&list=RDCmf5DTypcZg&start_radio=1

Track 12:

AZTEC CAMERA: ‘Somewhere in My Heart’:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kbaF8jLCxtc&list=RDkbaF8jLCxtc&start_radio=1

Track 13:

CLIFF RICHARD: ‘Mistletoe and Wine’:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rZCEBibnRM8&list=RDrZCEBibnRM8&start_radio=1

Track 14:

SHAKIN’ STEVENS: ‘Merry Christmas Everyone’:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=N-PyWfVkjZc&list=RDN-PyWfVkjZc&start_radio=1

Track 15:

BAND AID: ‘Do They Know It’s Christmas?’:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RH-xd5bPKTA&list=RDRH-xd5bPKTA&start_radio=1