To round off series three of First Last Anything conversations, it was an utter delight to chat to producer, director and filmmaker Jamie Muir. Jamie has worked for fifty years in television, joining ITV company London Weekend Television in the mid-1970s as a researcher on the weekly arts series Aquarius. He was part of both the respective teams that created and developed Aquarius’s successor, Melvyn Bragg’s The South Bank Show for LWT from 1977, and The Late Show, a nightly BBC2 arts magazine that ran for six years from 1989–95. He also produced Book Four, a regular books series in the early years of Channel 4, hosted by Hermione Lee.

Since 1992, Jamie has made a wide variety of documentary films and series, for BBC, ITV and Channel 4, on arts, factual and history, fronted by figures including Lucinda Lambton, Simon Schama, Alan Yentob, Tom Holland, and David and Jonathan Dimbleby.

There was a lot to ask Jamie, as you can well imagine – and there was the small matter of discussing music as well, plus early family life, especially with his dad Frank Muir, the extraordinary comedy writer and executive with a notable broadcasting career of his own. But over Zoom, one afternoon in late November 2025, we talked about some of Jamie’s notable record purchases, as well as the power of photojournalism, why humour in arts television is underrated, and even music that turns up too often in documentaries. We hope you enjoy our chat – and wish you the merriest of Christmases. See you in 2026.

—–

JUSTIN LEWIS:

What music do you remember first hearing at home? You mentioned when we were setting this up things like comedy records, musicals.

JAMIE MUIR:

Yes, definitely comedy records, so Peter Sellers, Songs for Swingin’ Sellers, and then things like Bernard Cribbins’ ‘Hole in the Ground’, Lance Percival’s ‘Riviera Caff’: those kind of things which we found hilarious. And then probably My Fair Lady, Oliver!, Carousel – those were the kinds of records my parents had. They also loved French chanson, so Edith Piaf, Charles Trenet… which they had on old 78s until I used them for target practice, and shot them up with an air rifle.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

You were how old at this point?

JAMIE MUIR:

Ten.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

This is about the time you’d have started buying records yourself, if I’ve got the maths right. It’s interesting you mention Peter Sellers. Your dad Frank co-wrote things with Denis Norden, like ‘Balham – Gateway to the South’, a very famous sketch Sellers did on record.

JAMIE MUIR:

Yes he did, he wrote two or three things for Sellers with Denis, and there’s one about a young pop star [Twit Conway], ‘So Little Time’, which is sort of based on Elvis. It’s got some great jokes in it:

‘Now I’ve got some money I’ve been able to move my old mum and dad into a small house.’

‘I bet they’re delighted.’

‘No, they ain’t, they was in a big house.’

JUSTIN LEWIS:

Your dad was one of the most familiar faces on TV when I was growing up in the 70s and 80s: Call My Bluff, My Music, all sorts of things. As with Denis Norden: I didn’t know there was this whole writing career that came before it. How aware were you as a child of all this?

JAMIE MUIR:

I was very small, but every Sunday afternoon, he would disappear, to record the weekly episode of Take it From Here for radio. And then during the week, he would go and write with Denis, who we knew as children. They were incredibly long runs, something like 35 or 40 episodes.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

For twelve years!

JAMIE MUIR:

Yeah, for twelve years. It was a ridiculous, extraordinary work rate. Then in summer breaks, they’d go off and script-doctor Norman Wisdom films.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

Oh my god, so it didn’t stop.

JAMIE MUIR:

No, it didn’t. And of course, because nothing was recorded… jokes had no long tail.

Talbot Rothwell was in the same writing stable, and when the series was over, he asked if he could borrow some jokes. Someone had typed all their jokes up in a book, they lent them to him, and that’s how ‘Infamy, infamy, everyone’s got it infamy’ ended up in Carry on Cleo.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

So that started in Take It from Here?

JAMIE MUIR:

They just said, ‘Sure, we don’t need it anymore.’

JUSTIN LEWIS:

There was probably this thought back then that this was all ephemeral.

JAMIE MUIR:

[With Denis], my dad also wrote something for television that’s a bit dubious, I suppose: Jimmy Edwards [from Take It from Here] as the headmaster of a school, who was very free with the cane.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

Oh yes, Whack-O!

JAMIE MUIR:

Which I remember loving as a child. And one of the boys in the film spin-off of that [Bottoms Up, 1960] went on to be a member of the Jimi Hendrix Experience. Mitch Mitchell, the drummer.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

What I was going to say about your dad’s connection with television and pop is that he was on things like Juke Box Jury [1962].

JAMIE MUIR:

He did quite a lot. When television came back after World War II [in 1946], I think he was an announcer. I’ve always meant to ask John Wyver about this because he’s about to publish a book called Magic Rays of Light: The Early Years of Television [out on 8 January 2026].

JUSTIN LEWIS:

Which I must get!

JAMIE MUIR:

I think Dad worked at Alexandra Palace really quite early on. And we were certainly unusual amongst my friends growing up. We were a telly household very early on too, I think late 50s.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

Oh, so ITV was up and running.

JAMIE MUIR:

Yup, and because Dad was an executive [in comedy] at the BBC in the 60s, he would watch everything, and we’d sit and watch with him and he’d ask us what we thought of it. So we were a family that watched television critically which was, again, quite unusual. [One night], I’d gone to bed and he got me up and said, ‘There’s a play on you might enjoy. It’s by a writer called Harold Pinter. And it’ll be quite strange, but it’ll also quite funny. So we watched the Tea Party [BBC1, 25 March 1965, repeated BBC2, 30 April 1965]. And that was magic.

And we’d also seen a production of Hamlet Live from Elsinore [BBC1, 19 April 1964, the night before the chequered launch of BBC2], with Christopher Plummer [and Michael Caine as Horatio]. That is etched in my memory as an early example of watching grown-up television.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

One thing I remember Denis Norden saying about his writing partnership with Frank: he recalled that Frank thought comedy was essentially a kindly medium whereas Norden, in his own words, ‘liked the bastards, the WC Fields and Larry Sanders’, the untrustworthy characters.

JAMIE MUIR:

There was a sort of slight Lennon and McCartney thing about the two of them. But what we sometimes forget is that back in those days, the comedy had to suit all ages, eight to eighty. Dad used to say, ‘It would have been nice to have been able to write for my peers.’ He was quite envious of the freedoms that came with alternative comedy later.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

I had often wondered what he thought of that era. Did he keep up with all that too?

JAMIE MUIR:

Oh god, yes. He loved Steve Coogan, The Young Ones, The Fast Show. He just didn’t like anything that he felt was a bit lazy – recycling old gags.

—-

JUSTIN LEWIS:

When did you start to think you’d like to work in television yourself?

JAMIE MUIR:

A bit later on – once I’d started watching arts programmes, I think, because I’d watch Monitor and then one presented by James Mossman called Review [BBC2, 1969–71], with this exploding television screen in the opening titles.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

And were you watching pop shows, entertainment shows?

JAMIE MUIR:

Absolutely. That Hughie Green show…

JUSTIN LEWIS:

Opportunity Knocks…

JAMIE MUIR:

That’s right: ‘Sincerely, folks!’ Crackerjack, obviously.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

Well, that’s where a lot of the pop groups would go.

JAMIE MUIR:

And then Sunday Night at the London Palladium on ITV. And I was there watching at home when John Lennon said on the Royal Variety Performance [4 November 1963]: ‘Those of you in the posher seats, rattle your jewellery.’ I saw those kinds of things go out, rather than see them in clip form later on.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

Because you wouldn’t have known, you couldn’t have known, that would happen.

JAMIE MUIR:

Yes, so that was incredibly exciting, to grow up in a household where something like television was just taken as a really valuable experience in terms of educating us.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

And did your parents observe what was going on in pop music because the generation gaps in those days were wider than they might be now? Were your parents up for rock’n’roll, generally?

JAMIE MUIR:

Yeah, they absolutely loved it, because the big influence – The Beatles – happened when I was nine or ten. I remember hearing ‘Love Me Do’ on a tiny little transistor radio. They kind of lived pop music through our enthusiasm.

And then very touchingly, Justin, after my sister and I left home, for many years, they’d carry on watching Top of the Pops because it had been part of our family life, sitting around commenting on the bands. So they just carried on. Dad, he died when he was 77 [in 1998], but even in those last few years, he could name all the members of Oasis. He had no kind of hierarchies in terms of knowledge, he was interested in everything. Each day, he’d get the Times, the Daily Mail and the Daily Mirror for the TV reviewing. So he would know what the poshos thought and also what the Mirror thought. Again, a big influence on my sister and I – the photojournalism in the Mirror. Taking the news in through images, rather than through masses of text.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

Well, in those days, with television, you’d see something and the chances are you wouldn’t see that again, or at least nobody expected to. So a photograph in a newspaper, that would be important. Which leads us neatly into the first record you bought, then…

FIRST: ELVIS PRESLEY: ‘Wooden Heart’ (1961, single, RCA Records)

JUSTIN LEWIS:

…because obviously Elvis never came to Britain – save for that ten-minute stop at Prestwick Airport – so how did you first become aware of Elvis? Did you see him on television somehow, was footage being shown there?

JAMIE MUIR:

Do you know, I think it was in either Egham or Virginia Water, in the newsagents, seeing Elvis Monthly, a little fan booklet, and I think I started asking Mum to buy me copies of that. And I possibly knew of Elvis through that magazine, these strong images – and then hearing ‘Wooden Heart’ on the radio. I fell in love with that and went out and bought it. So I think I came to Elvis through images rather than hearing the music. Then later on, my sister Sal and I became big fans of the films, and we’d go and see Girls, Girls, Girls or whatever.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

Because ‘Wooden Heart’ is from GI Blues, the first film after he left the army, isn’t it?

JAMIE MUIR:

Exactly. It’s quite interesting, because this song is safe, exactly what you would buy when you’re eight or nine, rather than ‘Jailhouse Rock’.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

It’s that middle section of his career where he’s an all-round entertainer, in between the rock’n’roll period and the Vegas period. It’s the in-between bit, not often discussed now, but he was selling absolutely zillions of records.

JAMIE MUIR:

I’m absolutely sure this was the first thing I bought with my own money. The next stage came when I bought ‘Concrete and Clay’ by Unit 4 Plus 2 (1965) – I just thought the lyrics to that were wildly romantic. Of course, The Beatles were romantic, but somehow, they were inextricably a part of my childhood. ‘Concrete and Clay’ was the beginning of my understanding older adult emotions in song, I suppose.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

I think Salman Rushdie heard this in his formative years too – you know he wrote a novel called The Ground Beneath Her Feet (1999), which led to a collaboration with Bono, but which started as the inspiration from ‘Concrete and Clay’. But you never know what records will cut through and stay with you, do you?

JAMIE MUIR:

I’m trying to be as honest as one can be all these years later.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

It’s a series of accidents, really. [JM agrees] And for once in this series, we’re going to switch round the order of Last and Anything, because I’m intrigued to know how you get from ‘Concrete and Clay’ to this, just a couple of years later?

ANYTHING: THE DOORS: Strange Days (1967, Elektra Records)

Extract: ‘Strange Days’

JUSTIN LEWIS:

It must have been incendiary to hear this at the time.

JAMIE MUIR:

The Beatles were becoming more and more surreal, but because I had grown up with them, they were never shocking. Not even Sergeant Pepper because it was clearly a continuum, and these were people you heard about through the newspapers or the telly – you were familiar with them as characters, and so the surrealism of the lyrics didn’t really strike me as something outrageously new.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

Also, the Beatles and George Martin have that connection with The Goons, the British sense of absurdism. George Martin even produced the Peter Sellers records we talked about earlier. But this, from America – that’s a different thing altogether.

JAMIE MUIR:

Probably through friends at school, I heard about this band called The Doors, and I asked for it for Christmas. The lyrics were something close to poetry, a poetry that you couldn’t quite understand.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

That feeling of ‘What does it mean?’ but also ‘Does it matter if I don’t know?’

JAMIE MUIR:

And that was kind of thrilling.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

Would you have gone to the Roundhouse concert (1968), because they didn’t play Britain very often?

JAMIE MUIR:

I saw the film [The Doors Are Open, Granada, December 1968], not at the time, I don’t think, but I do remember seeing a proto-pop video for ‘Five to One’ off the next album, Waiting for the Sun.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

I really hadn’t listened to The Doors for a long time before preparing for this interview, but I was at college when the film came out in 1991, the Oliver Stone film.

JAMIE MUIR:

Oh, where he shoots rock concerts like they’re battlefields.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

I always think of that bit where they’re noodling around, trying to come up with the ‘Light My Fire’ organ riff, and we chuckled a lot at that back then. Although watching Get Back, I’ve realised that sometimes that is exactly how a riff comes about. But some of Strange Days is absolutely terrifying.

JAMIE MUIR:

The spoken word interlude, ‘Horse Latitudes’, is so odd.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

That’s exactly the track I was thinking of.

JAMIE MUIR:

‘When the still sea conspires an armour…’

JUSTIN LEWIS:

Which Jim Morrison wrote at high school.

JAMIE MUIR:

Oh did he?

JUSTIN LEWIS:

I gather. So over here, this record must have seemed terribly exotic.

JAMIE MUIR:

And kind of adult, as opposed to the Beatles – who obviously were adult but came out of childhood… They were something you were beginning to grow out of. And after the Doors came Cream and Jimi Hendrix…

JUSTIN LEWIS:

On Strange Days, you get the Moog synth, the idea that the studio itself becomes an instrument. Apparently, they’d heard an acetate of Sergeant Pepper and decided, ‘We should do something like that’ because their first album had not been like that.

JAMIE MUIR:

Often people’s second album is a pale version of the first, but there really is a shift of gears with this, isn’t there?

—-

JUSTIN LEWIS:

So how did your career in TV start? Was Aquarius at London Weekend Television your first thing, ’74, ‘75ish?

JAMIE MUIR:

I did a history degree at University College in London and had no idea what I wanted to do, but right at the end of my time there, I was a kind of roadie for a poetry festival at Southbank [1973 at the Young Vic], just putting the leaflets on chairs. And Aquarius did an omnibus edition [eventually broadcast on ITV, 25 May 1974] where they took the best acts from the festival. I met the team then, and Humphrey Burton, the programme editor and presenter, was about. I said, ‘I’d love to work on Aquarius.’ And he said, ‘Well, I never take people straight out of university.’ I could see why, so I went off and got a job as an archaeologist – even though I don’t have any theoretical knowledge – working on Roman timber waterfront sites on the banks of the Thames.

Literally a year later, I rang up Aquarius and Humphrey said, ‘Okay, well you’d better come and have lunch, then. Can you come now?’ Which was kind of impressive. I said, ‘I’m not really dressed for it.’ He said, ‘No, come on, we’re very broad minded.’ I literally went in gumboots, and a jersey with a great hole in it. And he said to me, ‘Actually, we could do with some extra help with picture research.’ So I went in to do that once a week.

From there, I went to three days a week, and then full time for a couple of months. But then, to carry on, I had to be formally boarded, go through that process, because obviously it was very unionised in those days. But I got through that, and that’s when I joined properly as a researcher [1975] and had a fantastic 18 months with Humphrey and Russell Harty, and Peter Hall as well.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

What’s the earliest Aquarius film you can remember working on? The other day, I was watching a really nice little feature (via YouTube) about Erik Satie where LWT’s graphic designer Pat Gavin had made this animation [ITV, 2 July 1977].

JAMIE MUIR:

I wrote the script for that!

[Pat Gavin’s animation in full on Satie, Passing Through, can be seen here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3Xa4gGXE7YQ&list=RD3Xa4gGXE7YQ&start_radio=1]

JUSTIN LEWIS:

And that led me to other Aquarius items. I saw the Kyung Wha-Chung interview with Humphrey, after which she plays the Bruch Violin Concerto [ITV, 29 September 1974], which I feel almost certain I saw at the time. Because it had a spell on Sunday afternoons, that series, rather than late Saturday nights. And I even found this send-up of sports commentators that John Cleese and Eric Idle made for the strand [ITV, 14 August 1971). It’s interesting how arts programmes could be quite irreverent. People can often misunderstand arts TV, I think, they assume nobody involved has a sense of humour.

JAMIE MUIR:

Yes, later on [in the 1990s] I was able to make humorous documentaries with Lucinda Lambton, which were good fun to do, to have the licence to make something that was intentionally light-hearted and funny.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

People rightly talk up the Jonathan Meades documentaries, but Lucinda Lambton was also making a lot of things in that same spirit.

JAMIE MUIR:

I made a series with Lucy called Alphabet of Britain.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

I was watching the episode about concrete last night! [BBC2, 27 February 1995].

JAMIE MUIR:

‘These are stirring times for concrete…’ – it’s great being able to do a documentary where you can just put silly puns in. But anyway, in the early days, at LWT, I was taken on, along with a researcher called Nigel Wattis. And one of the early films the show made was about Andrew Lloyd Webber’s album Variations [made with his cellist brother Julian]. And we – Alan Benson the film’s director and I – suggested to Melvyn that it would make a good theme for The South Bank Show.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

Yes, one of the many variations of Paganini’s 24th Caprice.

[The Lloyd Webber film appeared in the second-ever South Bank Show, broadcast on ITV, Saturday 21 January 1978]

JUSTIN LEWIS:

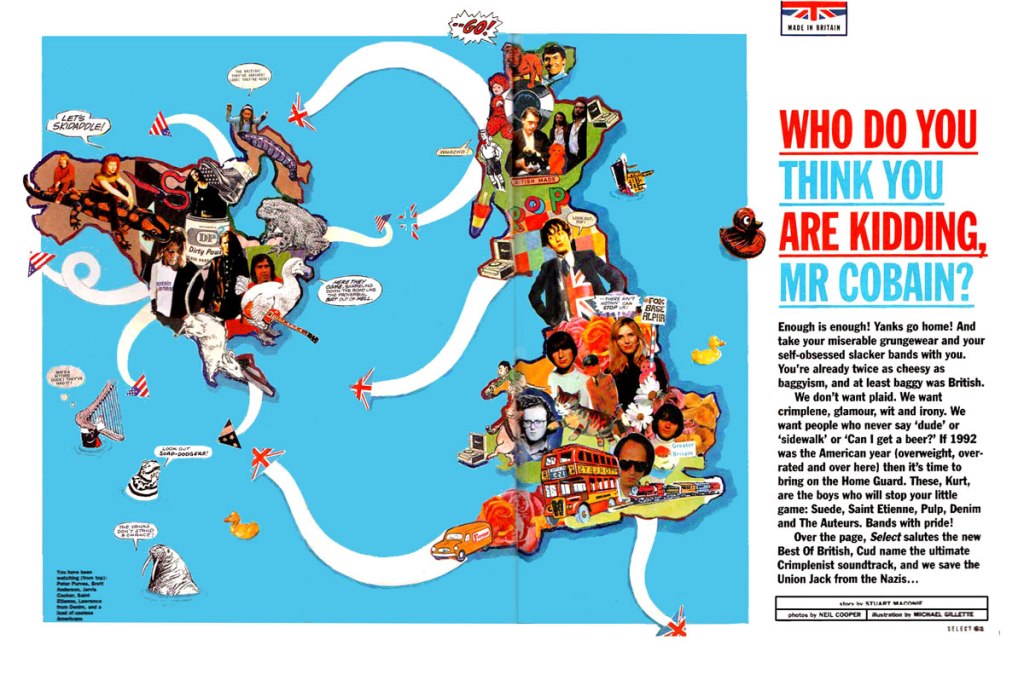

It’s interesting how The South Bank Show made a virtue of popular arts – it might do abstract art one week, but pop another week. I mean, Paul McCartney’s in the opening episode. Was that the intention, to make the spectrum as broad as you could?

JAMIE MUIR:

Yes, but us researchers were quite amused by the Paul McCartney choice because although it was a huge thing for Melvyn’s generation to make a gesture by interviewing McCartney first, really there was punk rock by 1978 [in fact Wings were at number one with ‘Mull of Kintyre’ as The South Bank Show premiered], so quite soon we had Patti Smith in the studio, my fellow researcher David Hinton worked on a film with Talking Heads and also a film about Rough Trade Records.

In that first year of South Bank Show, there was a slightly uneasy mixture between a shortish film of 20–25 minutes, and a panel review, like Saturday Review or Late Review later on. Melvyn and guests would review a book or play or something, and then he’d introduce the film. And, actually, none of us could manage that balance, we needed a bigger team for something like that.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

What would happen at the start of a series, then? You’d meet up and all suggest people or subjects to make films about?

JAMIE MUIR:

Exactly. That was interesting – there were four or five researchers on the team. Melvyn suggested we should hire consultants to feed what was going on into the programme. But I said, ‘I think we should be your consultants’, because I thought we’d be doing ourselves out of a job otherwise. So we divided the subject areas up between us and we made ourselves authorities in the different subject areas.

And then we’d have these seminars where we’d go up to the meeting room, there’d be cheese, grapes, a bit of wine, and we’d pitch ideas. It was a terrific process that Melvyn devised, because we’d be pitching against each other, and he’d say, ‘Don’t just suggest Spielberg, what’s the angle?’ So you were bringing him an idea, but also trying to conceptualise it. We had really good discussions out of that, he built a wonderful team – and we’re all still friends to this day. Because it wasn’t silly competitiveness, it was genuine intellectual competitiveness. ‘Is this the right moment to do William Golding or should we do a film on Coppola?’

JUSTIN LEWIS:

The other night, I was watching the film on Philip Larkin, screened [ITV, 30 May 1982] to mark his 60th birthday, but actually made a year earlier. And Larkin refused to be shown on camera, right?

JAMIE MUIR:

It was funny. Melvyn went up to see him in Hull. There was a lot of correspondence about where they were going to meet. They settled on the Station Hotel. And they had a bottle or two. Of course, in those days, closing time was rigorously enforced, and Melvyn said, ‘Come on, you’ve got to let us finish’, and Larkin said, ‘I do have a professional reputation in the town.’ I think the publican said he was going to call the police. Anyway, Larkin said he’d take part, but he didn’t want to appear. Though in fact, if you notice, the tip of his nose is in shot.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

I was thinking about how arts programmes would often be on after comedy shows. I think of Arena being on after Fry & Laurie. And The South Bank Show more often than not seemed to be on after Spitting Image on Sunday nights. There was something about both arts programmes and comedy shows that had this kind of playfulness, striving for innovation.

JAMIE MUIR:

I had a real salutary lesson early on with that. If you worked after a certain time, you were allowed to get a cab home, and cab drivers pulling into London Weekend were always interested in what shows we made. One asked me, ‘What show do you work on?’ I said, ‘The South Bank Show’, perhaps thinking maybe he wouldn’t watch it, and he said, ‘Oh! I saw the programme about Harold Pinter – I didn’t know he grew up in Hackney!’ So, never try to match people to subject matter. There are an infinite variety of ways in to a subject. And as a young person, that was a really important lesson. I often found that with The South Bank Show, people watched it for a whole variety of reasons.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

You’d be working on, what?, four or five films a series, because there seemed to be 26 a year.

JAMIE MUIR:

It felt like hard work, certainly.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

You’d be working on more than one at once, though.

JAMIE MUIR:

And they were pretty thoroughly researched. We didn’t have the internet then. It was all books and going to talking to people, and writing a careful brief, and then being on hand in the cutting room for any stills or extra visual material the director wanted. So it was a very rich and fulfilling role, researching in those days.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

Do you have particular favourite films that you worked on from those days?

JAMIE MUIR:

I think the most exciting was the programme with William Golding [broadcast on ITV, 16 November 1980 – his first interview in 18 years]. Because he’d sort of vanished. And I’d read Lord of the Flies, when I was about 13, 14, but hadn’t read anything else, and [in my mid-twenties] I read my way through the others. It was a fantastic body of work, and because I was working on the programme, I decided to ring up and see what he was up to. And Faber said, ‘He’s just finishing a novel, but he doesn’t want to do any publicity for it’ – it was a book called Darkness Visible [1979]. There’d been a ten-year gap before that one. And then they said, ‘But he has just started on a new novel, set on a ship [which became Rites of Passage, 1980], and he’s very upbeat about it – keep in touch.’

So every four months, I’d ring up: ‘How’s he getting on?’

‘Oh, he’s motoring away.’

And then, at one of these pitching sessions for the next series, I said to Melvyn, ‘Golding’s got a new novel out. I think this is the one we should cover.’

And Melvyn said: ‘Yes, but Anthony Burgess has got Earthly Powers. He’s a great talker.’

‘Yes, but Golding hasn’t done interviews for ages. He’s like a lost figure.’

So Melvyn wrote to him and Golding wrote back this brilliant letter: ‘What it amounts to is this. I’ve no objection to being filmed down here in what are my own surroundings so to speak; and no objection to talking in general terms on general topic (whither China, whatever happened to flying saucers, waterlilies, dragonflies and Homeric poetry,) but a quarter-of-a-century of churning out dreary answers to the dreary examination questions on my books or book has made me determined to give it, give it, up up up.’

Melvyn could see that he wasn’t actually objecting to a programme, so he went down to see him, and they got monumentally pissed. When he came back, I asked, ‘What have you agreed?’ And he said, ‘I can’t remember. All I remember is he dared me to walk along the wall around the pond in his garden.’

From the letter, we appreciated that he didn’t want to talk about the books, so I constructed a shape for the programme that would take them to places [around Wiltshire] which would then provoke discussion of the themes of the novels. We’d go to Stonehenge, Marlborough, and then Salisbury [which inspired The Spire]. And then the night before filming began, he said, ‘I will talk about the books as well.’ So I quickly had to prepare some questions about the books too. It was great because he wasn’t on the publicity circuit, and he responded incredibly openly to Melvyn’s questions. And then he went on to win the Booker Prize for Rites of Passage. I was personally extremely proud of landing a programme at exactly the right time.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

And also getting a kind of trust from the interviewee, not so much that their guard is down, but they’ve worked out this could be a different kind of interview.

JAMIE MUIR:

We really got to know contributors through their work, which I suppose is flattering for most artists. We’d done a programme on Scorsese in the States quite early on [22 February 1981 – there was a second profile in September 1988] and he then told other filmmakers, ‘Oh, The South Bank Show is a good place to go, if they contact you.’

[From 1988, the Bravo cable channel in the USA began broadcasting selected editions of The South Bank Show.]

JUSTIN LEWIS:

As we’re having this conversation [in late 2025], Melvyn Bragg has retired from In Our Time on Radio 4 after 26 years and over a thousand episodes – Misha Glenny is succeeding him as host in January. He’s had an incredible career what with that and decades of The South Bank Show and so many other things. What do you think you learned about programme making from Melvyn in those early days at LWT and from the team he assembled for the series?

JAMIE MUIR:

He was a hard task master – at one time or another we all got a bollocking, particularly in the first year when the programme was finding its feet. But he believed in teams, in working collaboratively. I think he consciously modelled The South Bank Show on Monitor where he had thrived. The big lesson we researchers learned from him was to think through the elements of a programme rather than just shout out names of possible interviewees. That and the value of research, which was a very LWT thing. Because there was also John Birt and Peter Jay on programmes like Weekend World and in newspaper articles [for The Times], developing the ‘Mission to Explain’ – [giving a subject context, less emphasis on sensationalism and presenting a greater understanding of a story’s issues]. That was influential.

—–

JUSTIN LEWIS:

How did it feel to be producing a programme on the opening night of Channel 4 in 1982?

JAMIE MUIR:

Bloody terrifying.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

You were like the fifth programme ever on Channel 4. This was Book Four, with Hermione Lee, just before the first ever Channel 4 News.

JAMIE MUIR:

It was scary because there were so many different publicists involved and we were just trying to steer our way through it. It had to be a studio-based show, although actually, it would have been better if we’d gone to authors’ homes, I think. It was quite formal, being in the studio, in a way that was beginning to seem old fashioned.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

It feels incredible to think how books coverage was once such an integral part of television, and how that’s mostly gone now.

JAMIE MUIR:

I resolve not to be bitter, or nostalgic about the past, but it’s true.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

It’s such a shame, because if you look at the archive from the sixties to the nineties, that extraordinary inventory of arts television, you wonder how the arts of the 2020s will be represented in the archives. I know we still have radio, and podcasts, but the visual content is vital too.

JAMIE MUIR:

What is the Adam Curtis of thirty years’ time going to draw on? That’s the sadness, that richness of archive isn’t going to be there.

—-

JUSTIN LEWIS:

In 1988, you moved from LWT to the BBC, and began working as a producer on a new nightly format for BBC2, The Late Show. How did that come about?

JAMIE MUIR:

It had been a very fixed world in arts television, there’d been Omnibus and Arena on the BBC, us on LWT, and then that summer Signals had begun on Channel 4. So the plates started to shift, and Kevin Loader – who’s gone on to be a film producer – rang up several of us at LWT. I think Mary Harron, who also went on to make feature films, was the one he rang first – a good friend of mine. And then Kevin rang me, and I thought, ‘This is the time to make a move’. Because the way the union worked, in order to direct, everyone had to go on a formal directing course either at LWT or at the Short Course Unit at the National Film School. And because I’d been doing Book Four, I was the last to get this kind of formal training. I’d managed to make one film, about Eric Gill, through the religious department at Channel 4 because they had slightly more money – and that had been a tremendous experience.

So after Kevin rang me, I joined the team that was conceptualising The Late Show. We spent an autumn devising it.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

Because Alan Yentob had just become BBC2 controller, a particularly rich period for the channel.

JAMIE MUIR:

It was a fantastic time, and the launch editor Michael Jackson [future BBC2 controller and also later head of Channel 4] was an inspiring person to work with. I was a nightly producer on The Late Show, a tough job, but I got the opportunity to make films and I made as many as I could.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

What you were saying earlier about the early multi-item era of The South Bank Show… The Late Show was four or five items a night wasn’t it? A film report, studio interview, bit of live music… So you were producer one night a week?

JAMIE MUIR:

Yeah, although it was mostly going into cutting rooms and saying to people, ‘Could you cut two minutes out?’ And they’d say, ‘Which two minutes?’ And I’d say, ‘Any two minutes, we’re going on air in six minutes.’ The pace was so hectic, compared with The South Bank Show. It was often quite difficult to work out what the elements of that night’s show would be – because somebody could die and [you’d have to react to that].

JUSTIN LEWIS:

And you were on straight after Newsnight.

JAMIE MUIR:

I think I would have benefited from a spell on Newsnight first.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

You also helped bring back Face to Face, with Jeremy Isaacs in the John Freeman role.

JAMIE MUIR:

Yes, I did two or three, and then Julian Birkett produced them thereafter. There was a studio producer called John Bush [another South Bank Show producer/director] who worked out the direction, because there’s a very small number of angles that they used in Face to Face. So that was learning from the past.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

You pointed me towards the Late Show film on Julian Cope [BBC2, 6 March 1991], which you made with Mark Cooper. And I remember seeing it at the time. I’ve always enjoyed him in interview mode – he goes from grand pronouncement to humorous to self-effacing to sincere and back again. An absolutely perfect interviewee because you’ll always get something different.

JAMIE MUIR:

I’d loved the Teardrop Explodes, ‘Treason’ and things like that. We made it just up the road from where I lived.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

I recognised the Brixton streets!

JAMIE MUIR:

He seemed very home-based. So I thought I’d make it as close to a home movie as possible, and not stray too far from his area.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

That’s a wonderful version of ‘Las Vegas Basement’ in that. Why do you think The Late Show came to an end? I know you’d already moved on.

JAMIE MUIR:

I suspect it was cost. It was expensive to run, and by then, I think the BBC was starting to think it needed to be competing with the output of the Discovery Channel. So the trend in arts programmes was to go for big CGI epics, do you remember that? The thing that was deemed to be incredibly successful was Jeremy Clarkson’s film about Isambard Kingdom Brunel [in Great Britons, 2002], and that was perceived to have cut through on a much bigger scale. Arts programmes were retooled to try and emulate its success.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

A bit like how if you make a science film, not to denigrate the people who make them, you have to have someone standing next to a volcano. Or something. You have to have the thought, ‘How’s this going to look spectacular on television?’

JAMIE MUIR:

Yes. There was also a fascination with that man who used to do lectures about storytelling, Robert McKee. And trying to get documentaries to conform to the three-act structure. I thought it would have been nice to have a crack at making that kind of thing, but then it vanished because of the banking crash in 2007, and the BBC was back to the middle ground again, which is where I flourished, the presenter-led programmes, that kind of thing.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

One thing that’s definitely increased in documentaries is the amount of music. It used to be that music was used quite sparingly, even in documentaries that were already about music. Were you choosing a lot of music clips yourself?

JAMIE MUIR:

Yes, both LWT and the BBC had these music departments with fantastic resources where more or less anything was available in physical form to listen to, but they’d also done these deals…

JUSTIN LEWIS:

There were blanket agreements?

JAMIE MUIR:

Yes, that was kind of thrilling. You could discover a favourite composer or song and work them in.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

Can you isolate one or two particularly special examples?

JAMIE MUIR:

A friend recommended a contemporary classical composer called Howard Skempton. His work, anything he did, worked so beautifully with images. I loved working with his music. He wrote a piece called ‘Small Change’ that has got the inevitability of a Beatles tune, it’s so perfect. You feel it’s existed forever. He also wrote a magnificent orchestral piece called ‘Lento’ (1991).

When I made a film for Imagine… about Barbara Hepworth (BBC1, 18 June 2003)…

JUSTIN LEWIS:

Oh that was an excellent film, was rewatching it in preparation for this…

JAMIE MUIR:

…I rang him up to ask if I could use a piece of music he had written in memory of Barbara Hepworth. When I called he said, ‘Oh I know you! You’re the one who’s always using my music.’ I said, ‘Oh God, has it always been appropriate?’ And he said, ‘That doesn’t matter. It’s just good that it’s in circulation.’

JUSTIN LEWIS:

Oh, that’s nice.

JAMIE MUIR:

He was so generous. I wish I’d pushed it a bit further and asked him to compose original music for a project.

What was funny was the people who worked in the BBC music department put up this list, pinned to the wall, of Music We’d Like to Ban [from documentaries etc]. It said, ‘All Michael Nyman.’

JUSTIN LEWIS:

I was about to ask, is Philip Glass on that list? Who I love, but I’m sure his work has been in everything by now.

JAMIE MUIR:

Yeah, all Philip Glass. ‘Ferry Cross the Mersey’ for any programme about Merseyside. ‘Let’s Make Lots of Money’ for any consumer programme about the 80s. It was so accurate, that list. I hope somebody keeps that list when they close the department.

——

LAST: LAURA CANNELL: The Rituals of Hildegard Reimagined (2024, Brawl Records)

Extract: ‘The Cosmic Spheres of Being Human’

JUSTIN LEWIS:

I know a little about Laura Cannell, I bought one of her albums a little while back, The Sky Untuned (2019), which was quite violin-centric. And this, which I’ve come to late, but which I’ve been playing a lot, is much more recorder-centric. How did you discover this? Did you know her stuff?

JAMIE MUIR:

No – it was good old BBC Radio 6 Music. I heard it when I was cooking one evening. I love the fact this draws on the past but is contemporary. I thought that balance of the two is tremendously appealing. And as well as the music, the fact it was recorded in an old church. I love that sort of gesture.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

It occurred to me, as with The Doors earlier but in a different way, it’s got that element of sound distortion, the treatment of the instrumentation… You’ve got her playing a bass recorder, a twelve-string knee harp, a delay pedal. And that’s it. And as on The Sky Untuned, the instruments start to sound quite otherworldly, not like themselves.

JAMIE MUIR:

Yes, it could have strayed off into New-Agey yoga music, but I found that weight of history behind it very attractive.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

It’s quite ghostly, isn’t it.

JAMIE MUIR:

It is. I am drawn to that kind of Ghostbox sound.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

Me too.

JAMIE MUIR:

I love the wit of it, I think. But I do also have a kind of seasonal taste in music. In autumn and winter, I’ll listen to more classical, more English folk-rock – the music of my teenage years, like Shirley Collins. I love her album Heart’s Ease, especially ‘Locked in Ice’. Then in the spring and summer, I’ll listen to ska – The Skatalites’ version of ‘I Should Have Known Better’ is a favourite – and reggae, and the things that my children recommend. It’s quite a profound yearly cycle.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

What are your children recommending you at the moment?

JAMIE MUIR:

They’re very big Harry Styles fans, I love playing that in the car. My middle one is a big fan of Florence and the Machine and she grew up quite near where I live, so we all recognised quite a lot of the references in a song like ‘South London Forever’. What else do they like? Quite a lot of jazzy things at the moment.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

Ezra Collective?

JAMIE MUIR:

Exactly. Oh, and that band Haim.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

When you were saying earlier about how your parents carried on watching Top of the Pops for many years… you’re also keeping that connection going, of keeping up to date. How old are they?

JAMIE MUIR:

They’re 33 to 26.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

And what are you working on now? Because you’ve done fifty years of television.

JAMIE MUIR:

I thought I’d reinvent myself as a small-scale filmmaker. I bought a Blackmagic camera, which is the price of a laptop, but actually, it’s quite difficult to operate and you spend all your time fiddling with it rather than talking to the person you’re filming. And while you could shoot a feature film on it, it seemed to be taking me forever to learn the camera.

So at the moment, I’m making things on my phone, which is fantastic because it’s quick. My neighbour is a historian called Tom Holland, who does The Rest is History.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

You’ve made some films with him before, haven’t you?

JAMIE MUIR:

Yeah. And he led the campaign to try and stop the Stonehenge tunnel going through the World Heritage Site. We shot this thing in half a day, and there was an article in The Times that linked to this tiny little film. Which was extraordinary. And I also made a film on my phone with my wife –Caroline’s a fundraiser – who wanted a short video for the charity she works for. So that kind of thing is what I’m doing now. Learning how to do that, doing charity videos, things with Tom, a range of bits and pieces.

—–

JUSTIN LEWIS:

Just looking at my questions list. We’ve covered most of it, I think. What’s left?

JAMIE MUIR:

The other Jamie Muir!

JUSTIN LEWIS:

Oh yes – have you ever been confused with the Jamie Muir in King Crimson?

JAMIE MUIR:

Yes, all the time. Because I was doing programmes about books, I was in a pool of people who’d be invited to book launches by Faber & Faber. And I was invited to the launch of the Faber Book of Political Verse, which had been edited by the then-Home Secretary, Kenneth Baker. Joanna Mackle at Faber introduced us:

‘So this is Jamie Muir who works on The South Bank Show.’

Kenneth Baker says, ‘Jamie Muir? My brother-in-law’s called Jamie Muir. He’s the percussionist with a band called King Crimson. Do you know Larks’ Tongues in Aspic?’

JUSTIN LEWIS:

It’s not a sentence you’re expecting from the Home Secretary, really. Especially not then.

JAMIE MUIR:

There’s been a film quite recently about King Crimson, a really good one [In the Court of the Crimson King, 2022]. The director Toby Amies rang me up, wondering whether I was that Jamie Muir, and I suggested he included a section on people who were mistaken for him. Sadly, he’s died now, but I wondered if people had ever asked him what it was like working with Simon Schama.

——

You can follow Jamie Muir on Bluesky at @jamiembrixton.bsky.social.

——

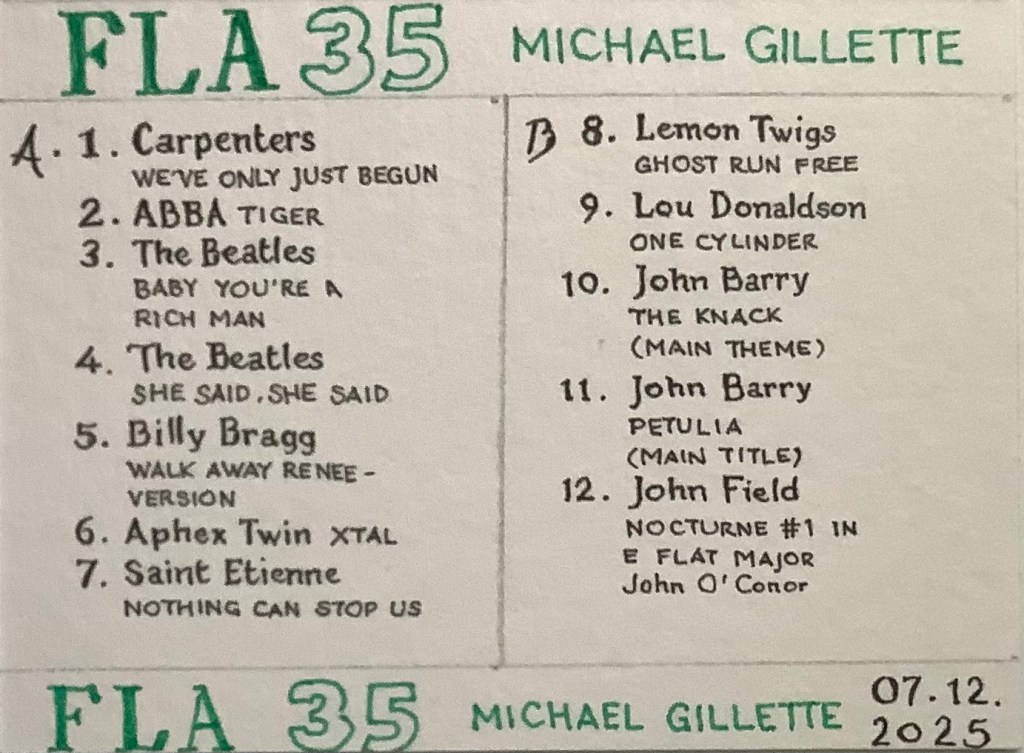

FLA Playlist 36

Jamie Muir

(For the time being, this site and project uses Spotify for the conversation playlists, but obviously I disapprove that Spotify doesn’t pay artists and composers properly, and other streaming platforms are available, as are sites to buy downloads and buy recordings. For consistency, you can also listen to the selections via YouTube (where available), and links are provided in each case, below.)

Thanks to Tune My Music, you can also transfer this playlist to the platform or site of your choice by using this link: https://www.tunemymusic.com/share/xj8YbZXFOI

Track 1:

PETER SELLERS: ‘So Little Time’:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FacRB8U0xiI

Track 2:

ELVIS PRESLEY: ‘Wooden Heart’:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=k5RO_RSI8QM&list=RDk5RO_RSI8QM&start_radio=1

Track 3:

UNIT 4 PLUS 2: ‘Concrete and Clay’:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1CEQ640sHr8&list=RD1CEQ640sHr8&start_radio=1

Track 4:

THE DOORS: ‘Strange Days’:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tHOK87ozcho&list=RDtHOK87ozcho&start_radio=1

Track 5:

THE DOORS: ‘Horse Latitudes’:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=oVWNkW21BeA&list=RDoVWNkW21BeA&start_radio=1

Track 6:

THE DOORS: ‘Five to One’:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=oOzpncIHCLs&list=RDoOzpncIHCLs&start_radio=1

Track 7:

ANDREW LLOYD WEBBER: ‘Theme and Variations 1–4’ (based on Paganini’s 24th Caprice in A Minor):

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0WnX5zYznIc&list=RD0WnX5zYznIc&start_radio=1

Track 8:

THE TEARDROP EXPLODES: ‘Treason’:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cn9zRk_2-GE&list=RDcn9zRk_2-GE&start_radio=1

Track 9:

JULIAN COPE: ‘Las Vegas Basement’:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Sdeu37Focqc&list=RDSdeu37Focqc&start_radio=1

Track 10:

HOWARD SKEMPTON: ‘Small Change’:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZQIoW_iFPlE&list=RDZQIoW_iFPlE&start_radio=1

Track 11:

HOWARD SKEMPTON: ‘Lento’:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BCGhH_N_Ovc&list=RDBCGhH_N_Ovc&start_radio=1

Track 12:

LAURA CANNELL: ‘The Cosmic Spheres of Being Human’:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uCy6y8VKwYI&list=RDuCy6y8VKwYI&start_radio=1

Track 13:

LAURA CANNELL: ‘The Rituals of Hildegard’:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Fb8GXhsDBRs&list=RDFb8GXhsDBRs&start_radio=1

Track 14:

SHIRLEY COLLINS: ‘Locked in Ice’:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ekmpu0ippKY&list=RDekmpu0ippKY&start_radio=1

Track 15:

THE SKATALITES: ‘I Should Have Known Better’:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=p7SL5iO0x1c&list=RDp7SL5iO0x1c&start_radio=1

Track 16:

HARRY STYLES: ‘Golden’:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=enuYFtMHgfU&list=RDenuYFtMHgfU&start_radio=1

Track 17:

FLORENCE & THE MACHINE: ‘South London Forever’:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lua-N4OrPKA&list=RDlua-N4OrPKA&start_radio=1

Track 18:

KING CRIMSON: Exiles:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nMeFafKx7GI&list=RDnMeFafKx7GI&start_radio=1