Journalist, travel writer and editor William Ham Bevan has worked for nearly every national newspaper in Britain at some point over the past 30 years, plus a raft of magazines and other publications. When I first met him, about 45 years ago, when we lived in the same street and our mums were best friends, we used to talk endlessly about our twin obsessions: pop music and ridiculous TV programmes. His perceptiveness and wit has only grown since then. On the one hand, he is one of the most brilliantly professional journalists I’ve known. He is also the first person I knew who posted something on the world wide web: in around 1996, when we hadn’t seen each other for a while, I happened to find a post by him in a discussion about the scariest TV logo, and he nominated the Yorkshire TV chevron. Especially when it moved, at the start of the Ted Rogers game show 3-2-1. Don’t have nightmares.

We talked over Zoom one afternoon in early September 2025, covering such conversational terrain as: being lucky enough to have parents who are open-minded about music, keeping old tapes of the top twenty, synthesizers, schools TV soundtracks, and why sometimes humour should belong in music.

—-

JUSTIN LEWIS:

So what’s the first music you remember hearing? What sort of music was being played in your home?

WILLIAM HAM BEVAN:

Well, it would almost certainly have been on Swansea Sound. When I was living with my Mum and my grandfather, from 1974 till 1980 when we moved to Mumbles, I remember music being on in the background pretty much all the time. It was almost always Swansea Sound – commercial chart music. I was always quite aware of tunes that were in the charts: ABBA, the Bee Gees, or the songs from Grease. And Showaddywaddy obviously, because they never seemed to be off the charts.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

Always available.

WILLIAM HAM BEVAN:

Top of the Pops would be the other thing, which we watched each week. Mum would have been in her mid-thirties at the time. Grandpa would watch it too – he’d come in, and he’d have three stock phrases. One would be: ‘Why do they keep dancing around? They’d be able to play a lot better if they stood still.’ When Legs and Co or whoever the troupe was at the time came on, he’d say, ‘God, I’ve seen more meat on a skewer.’ And then, at some point, he’d excuse himself and go out to roll a fag, saying, ‘Well at least they look as though they’re enjoying themselves.’

I reckon he looked forward to those five minutes of performative bemusement every Thursday night. Look at the costumes, shake your head, go out to the kitchen.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

Pop TV now has this understanding that pretty much everyone alive has a connection with pop as we know it because rock’n’roll is seventy years old, so if you’re aware of that tradition, you’re familiar with it. But back then, there were these very wide generation gaps.

WILLIAM HAM BEVAN:

Back in those early years, I don’t remember much pop on TV beyond Top of the Pops, Tiswas, Swap Shop… and obviously those fillers on HTV when they’d play videos of ‘Wuthering Heights’ or whatever because a live broadcast had finished three minutes early.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

Or they hadn’t sold enough advertising.

WILLIAM HAM BEVAN:

Indeed. But record collections… Grandpa was very much into big band stuff like Count Basie, but he was quite open-minded, as were Mum and Dad. There was no real consideration of genre – if they saw something or they heard something they liked, then they’d get it.

When it was the US bicentenary in 1976, there were a lot of broadcasts from the States of military parades and tattoos. Gramps actually wrote to the US embassy saying he really enjoyed some of this music that was played, and wondered what it was and how he could buy it. About two weeks after that, a huge package wrapped up in ribbons turned up on the doorstep, from the US embassy: it was about seven or eight box sets of LPs, some of them pressed on red, white and blue vinyl. I’ve still got some of them – things like ‘A Bicentennial Salute to the Nation from the United States Guards band’.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

There’s going to be a lot of Sousa, isn’t there?

WILLIAM HAM BEVAN:

Yeah, I think the Monty Python theme [‘The Liberty Bell March’, composed 1893] is probably in there somewhere.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

So did your grandfather’s interest in big band music lead to this amazing interest in music in his children?

WILLIAM HAM BEVAN:

I’m not sure how the Hams came to be such a musical family – although we were really only two-thirds of a musical family. My Mum had two brothers: John was a jazz trumpeter, had a music shop in town, and had a jazz radio show on Swansea Sound. And then you had Pete, who’d been in Badfinger, and tragically ended up taking his own life. But Mum was the cuckoo in the nest. I mean, she tried learning violin when she was at school. She was a bit of a tearaway, apparently – I used to have one of her old end-of-term school reports, and the headmistress had written, ‘Wicked without malice’. She fell off the roof of the school – no idea what she was doing up there – and she injured both of her arms. Her violin teacher said, ‘Well, let’s take that as a sign from God.’ That was the end of her musical ambitions, and I’m afraid I’ve taken after her, rather than John or Pete.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

Didn’t you do some keyboard playing, though? I seem to remember, though this was after my time, that you were in a band at school.

WILLIAM HAM BEVAN:

I did muck about with synths. We used to cover ‘The Perfect Kiss’ by New Order, because if you look at the Jonathan Demme video, quite a lot of it is close-ups of Peter Hook’s fretboard and Gillian Gilbert’s keyboards. So it actually shows you how to play it. And yes, we did do one gig at the Bishop Gore Comprehensive school hall. There’s one surviving tape of it, and I keep it under lock and key.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

What else was in your set, then?

WILLIAM HAM BEVAN:

We did ‘Everything Counts’ by Depeche Mode. And then we did ‘Tainted Love’ and something very odd happened to the sequencer, halfway through. It started hammering out tom-toms on the drum machine, turning the song into a mash-up of something not far off ‘Atrocity Exhibition’ by Joy Division. Our set was followed by two heavy metal acts, and that was a salutary tale, because people had been politely sitting down in the hall during our set, but once the metal band came on, the whole stage was swamped and there were people moshing in the front. And we thought, Oh, okay…

JUSTIN LEWIS:

It’s always been a big rock town, has Swansea. But your mum, who was a great friend of my mum’s – this is how we know each other – and who I was terribly fond of, had worked in telly for a bit, at Thames Television in London.

WILLIAM HAM BEVAN:

She didn’t spend a long time at Thames, but she did hang round with a lot of people from that scene… a Fleet Street crowd. People like the This Week presenter Llew Gardner – she was his PA for years – the Parkinsons, Michael and Mary, and Hugh McIlvanney. And she’d been part of that quote-unquote Swinging London world. There were so many tales that she’d start telling me and would then say, ‘I’ll tell you the rest when you’re older’; sadly, she died when I was 17, so she never had the chance to. She’d mention stuff like having been present at the party where Germaine Greer’s husband walked out on her – apparently everybody was smashed out of their heads – or going to see the England v Scotland football international with Telly Savalas. It turns out he was a sports producer and reporter before he got into acting.

But to bring it back to music, she knew a lot more than she let on about. She didn’t often volunteer it, and I think that had a lot to do with what happened to Pete. I think she almost felt guilty, and didn’t like to think too much about what she used to listen to, because she loathed what the music business did to her brother and it was bound up in all of that.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

Actually, I can remember being about 11 or 12, this was the early 80s, and being this curious pop obsessive, and trying (innocently, I think) to ask your mum about Pete and his career – I knew he’d died tragically young but I didn’t know how it had got to that – and she understandably changed the subject very abruptly.

WILLIAM HAM BEVAN:

What did connect us, though, was The Rock’n’Roll Years [a presenter-free programme using news footage, music clips and captions, running on BBC1, 1985–87, and covering the years between 1956 and 1979*), one of the few programmes we’d watch religiously as a family – it was that, M*A*S*H and Ski Sunday. But things would come on The Rock’n’Roll Years, and Mum would make remarks… a band like Nazareth would appear and she’d say, ‘Oh I went to see them once’, and you’d think, Hm, that doesn’t strike me as being very you.

[*A further Rock’n’Roll Years series covering the 1980s aired on BBC1 in 1994.]

JUSTIN LEWIS:

I think as a young person, though, you quite often go and see all sorts of things, just because you go out. Regardless of what it is.

WILLIAM HAM BEVAN:

That programme was a massive piece of my education in rock and pop music – probably second only to coming over your house, reading Smash Hits and hearing your latest purchases. It was so well put-together, and not all the musical choices were obvious. you even had some album tracks, like ‘Hairless Heart’ by Genesis or ‘Medicine Jar’ by Wings, which I didn’t identify till years after.

I genuinely believe The Rock‘n’ Roll Years should be part of the National Curriculum. The downside is that even now, some songs are firmly linked in my mind with the news images played over them. ‘Life on Mars?’? That’s the Russian Concorde blowing up at the Paris Air Show. ‘Tubular Bells’? The IRA bombing Oxford Street. And unfortunately, Cyril Smith winning the Rochdale by-election for Alice Cooper’s ‘Elected’.

—–

JUSTIN LEWIS:

Something we both had as kids, now, but we didn’t know about at the time because we didn’t know each other: we each had one tape of the Radio 1 top 20. Yours is from Sunday 18 September 1977, when the number one is Elvis’s ‘Way Down’. Mine is from Sunday 2 April 1978, when the number one is ‘Wuthering Heights’.

(The dates above refer to the Sunday broadcasts for that week’s top 20 singles chart, but are officially dated for the previous day, ie the Saturday. You can find the full chart for that week in September 1977 here, and the full chart for that week in April 1978 here.)

JUSTIN LEWIS:

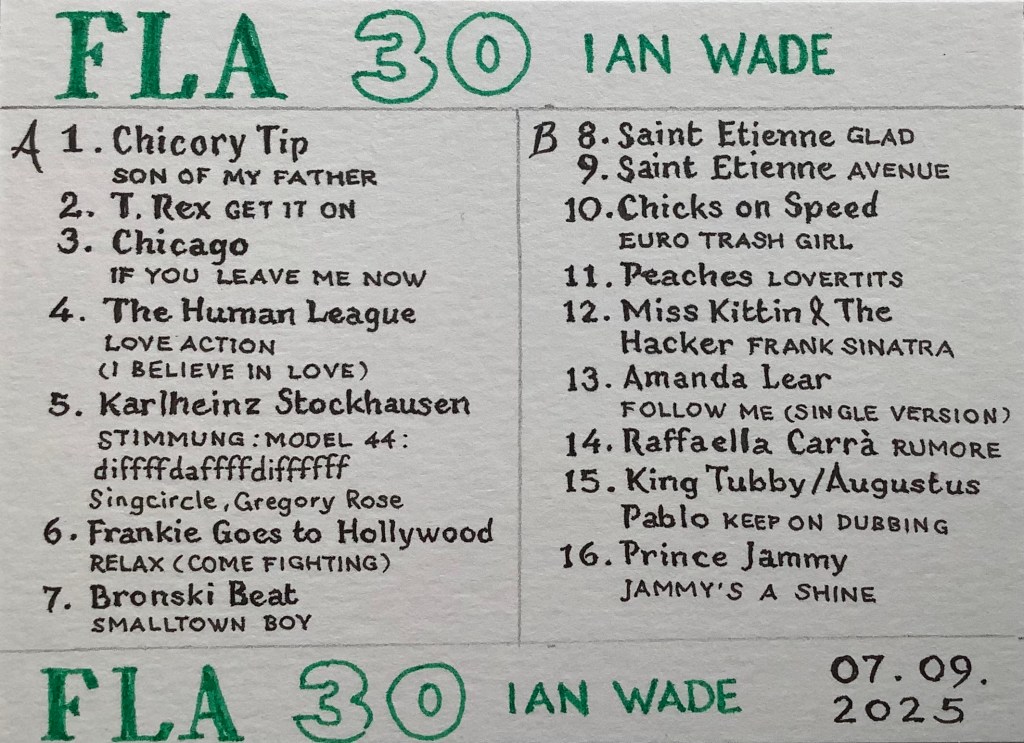

When I spoke to Ian Wade for the last episode [FLA 30], he described this multi-artist K-Tel compilation he owned as a small child as having ‘all the food groups’ in music, it had lots of different genres present. And these top 20s we had on tape, before we started buying our own records, have that same sort of air. I would say my tape has about fourteen belters on it out of twenty, and even the novelty records have a charm to them. I had my favourites – Blondie, Kate Bush, Costello, Nick Lowe, Darts – but I would often put the tape on and play all of it, no skipping ‘Ally’s Tartan Army’ or Brian and Michael. I’d just leave it running.

WILLIAM HAM BEVAN:

Yeah, I felt like it was cheating to skip songs. This sounds such a very odd thing to say in the streaming era – where, in one click, you can get just about and track you want – but I was insanely superstitious about cassettes. I always felt as though if you listened to one side, you had to listen to the other. Even if I didn’t particularly like one side of the cassette, I would force myself to listen, because the artist had put as much effort into side two as side one. It’s such a bonkers way of thinking.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

But it’s listening to an album as an album, though – as a complete piece of work.

WILLIAM HAM BEVAN:

It’s the same with this chart cassette. I’ve still got it, with all Tom Browne’s links. Terrible sound quality, as the tape has degraded, but you can just about make it out. And at the end of the one of the sides, my grandfather managed to tape over the end with a recording of the three-year-old me singing ‘A Bonnet Made of Lace’, which I think cuts off part of ‘Float On’ by the Floaters.

Inevitably, I’ve made that top 20 into a Spotify playlist. A few months back, one song – Carly Simon’s ‘Nobody Does it Better’ – suddenly became unavailable, and it really pisses me off when anything like this happens. It drives home to you that not only do you not own any of this music, you don’t even own the rights to listen to it. It’s entirely at somebody else’s whim whether you’re permitted to or not. Entirely my own fault for using Spotify, of course. I hate myself for it, but I’m a heavy Spotify user, and I was an early adopter.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

Space’s ‘Magic Fly’ in there, the nostalgia rush for me there was just ludicrous.

WILLIAM HAM BEVAN:

Having ‘Magic Fly’ at number two in that top 20, and ‘Oxygène’ by Jean-Michel Jarre at number four, very similar in some ways – both gateway drugs for me and electronic music. And there’s another synth-tinged instrumental in that chart, ‘The Crunch’ by the Rah Band.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

Which is a bit like an electronic cover of ‘Spirit in the Sky’.

WILLIAM HAM BEVAN:

Yes, now you mention it.

——

FIRST: 10cc: The Original Soundtrack (Mercury Records, album, 1975)

Extract: ‘Une nuit à Paris’

WILLIAM HAM BEVAN:

I’d had other records bought for me before I bought this 10cc album. The first one I remember was ‘Mississippi’ by Pussycat (1976), so I’d have been about two when it came out – I’d probably tried to sing along with it once, and then Mum thought, Oh I’ll get this for him. Pink Floyd’s ‘Another Brick in the Wall (Part II)’ – that was another one.

But Original Soundtrack was the first tape that I went and paid cash money for – probably with a fiver from a Christmas card. Phonogram had a low-price reissue series in the mid-80s called ‘Priceless’ and all the early 10cc albums were in that range. Dad already had the 10cc Greatest Hits [1972–78] compilation, which I absolutely loved. But I wanted the cassette of this. I didn’t like handling vinyl records – media people lionise vinyl, but I hated it, I was paranoid about scratching them.

In terms of getting hold of old stuff, reissue labels were an absolute boon, something that’s been quite forgotten. That EMI bargain imprint, ‘Fame’ – we had loads of those tapes in the house. You could buy them from filling stations and newsagents, along with all sorts of other weird and wonderful stuff on the Music for Pleasure label. In places like Lewisnews in Mumbles, there’d be a carousel of tapes by the counter.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

Can you remember where you bought this from, then?

WILLIAM HAM BEVAN:

I can’t, I’m afraid. I can tell you where I got my third-ever cassette, which was 10cc’s previous album, Sheet Music (1974). I know I got that from the David Morgan’s department store in Cardiff, because I still have the till receipt from February 1986 in the cassette sleeve – you kept those in case the tape got chewed up. Original Soundtrack would have been the year before that. And my second purchase, in between Original Soundtrack and Sheet Music, was Jean-Michel Jarre’s Oxygene.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

So you’d have known the 10cc singles from your dad’s compilation, but can you remember how you reacted to something like the ‘Une nuit à Paris’ suite that opens The Original Soundtrack?

WILLIAM HAM BEVAN:

I was about eleven when I bought this, and before that, I thought albums were just collections of singles or songs. I didn’t realise they are things that are supposed to work together, or have suites that could take up an entire side of tape. But this cassette also lacked a lyric sheet, and generally early on with cassettes, the packaging was an afterthought. If you wanted the big sleeve with all the artwork, you had to opt for the LP.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

Yes, a convenience thing when it came to the cassette format.

WILLIAM HAM BEVAN:

It was a couple of years later that I saw the proper gatefold sleeve of the LP, which had the lyrics inside. The lyrics for ‘Une nuit a Paris’ are presented like a rock operetta, with all the characters’ names and lines. Now, one factoid you tend to see all over the Internet is that it was the inspiration for ‘Bohemian Rhapsody’ [released in October 1975, seven months after Original Soundtrack], but I’ve never seen reliable evidence for that. I think it’s just that they sound similar – they’re trying to achieve similar things and they were quite close in time.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

I’ll tell you who I thought of when I was listening to ‘Une nuit a Paris’ yesterday: vocally it sounds like Neil Hannon! But reading around, I found some interesting quotes about this record. I’m sure you know all these, I know you’re a very big 10cc fan. The band’s Eric Stewart said this: ‘When “Une nuit a Paris” first came out, it was passed off as a “10cc trying to be funny again” track.’ And then Kevin Godley is quoted as saying that it was supposed to be ‘a serious piece of music… but someone dismissed it as an extended piece of fun which pissed me off.’

Now – 10cc often got accused of ‘cleverness for the sake of it’, and if you are creative and imaginative in how you make records, it leaves you open to a charge of cleverness. What are your feelings about that, and how do you process their serious tracks and their more frivolous work?

WILLIAM HAM BEVAN:

Maybe it goes back to that Frank Zappa album title, Does Humour Belong in Music? I think it does, but it’s something that really seemed to fall out of fashion from the late 80s into the dreary, earnest 90s – this idea that you can be humorous, arch, witty, and still be writing serious and credible music. Anything that’s lyrically funny almost gets written off as throwaway.

Some of 10cc’s songs are absolutely beautiful: things like ‘Fresh Air for My Mama’ on the first album (10cc, 1973) or ‘Old Wild Men’ and ‘Somewhere in Hollywood’ on the Sheet Music album (1974). That one’s Godley and Crème par excellence. I mean that’s probably them pushing godleyness and cremeliness as far as it can go.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

Cremeliness is next to Godleyness.

WILLIAM HAM BEVAN:

Yes, I thought we’d get round to that one. And another thing that’s all over the Internet with 10cc: they’re forever compared to Steely Dan. OK, they have the studio perfectionism in common and the musicianship – though that’s something often overlooked with 10cc…

JUSTIN LEWIS:

There’s a bit more jazz in the influence with Steely Dan, I think.

WILLIAM HAM BEVAN:

But where it falls down for me is that both Steely Dan and 10cc had spent time as songwriters for hire. Both paid their dues in Brill Building, Tin Pan Alley-type settings – having to come up with quotas of songs, quickly. Steely Dan loathed having to do that, they felt they were degrading themselves. Whereas all four members of 10cc did it, but there’s still this residual affection about that pop sausage machine – even if they did satirise it in stuff like ‘Worst Band in the World’.

As for the humour with 10cc, a lot of it sailed over my head at the time. I didn’t have any knowledge of the common tropes of Jewish humour, and they are a very Jewish group, when you look at the set-ups and pay-off lines: ‘Art for art’s sake/Money for God’s sake’. But it’s also very British. It’s like I’m Sorry I Haven’t a Clue: they can’t resist the obvious pun or the cheesy joke. That’s something I love. Lines like ‘It’s me that’s been dogging your shadow/It’s me that’s been shadowing your dog’ [from ‘Iceberg’, 1976] or ‘Waiters mass debating my woman’ [from ‘Don’t Hang Up’, 1976]. Part of me thinks, ‘Oh for God’s sake’, but I also find it endearing – that they probably know it’s terrible but they can’t resist it.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

There’s often this thought process with pop: don’t put anything in that will jar, or which could put people off you. Better to have something bland and beige rather than ‘what the hell are they on about?’ Which is sometimes a shame, because the mystery is part of the allure.

WILLIAM HAM BEVAN:

With 10cc, if you counted up all the songs, the majority of them are written from the point of a view of a fictional protagonist. That’s one aspect where the Steely Dan comparison does hold water. It’s generally someone very unsavoury, a low life. You have stalkers, voyeurs, even a talking timebomb that’s about to blow up a jumbo jet [‘Clockwork Creep’, off Sheet Music]. It’s always risky, because there are people keen to take lyrics at face value, and assume it’s the singer venting their own sentiments. Why can’t music be dramatic in that sense of the word? When Hamlet’s giving a soliloquy, you don’t think ‘That’s what Shakespeare thinks.’ That’s a terrible analogy, but you know what I mean.

—–

LAST: RON GEESIN: Basic Maths (Trunk Records, album, 2024)

Extract: ‘Welcome to Mathematics’

JUSTIN LEWIS: This might be a contender for the most niche choice so far in our 31 episodes… and yet, to anyone who watched or experienced schools television in the UK around the turn of the 1980s, they will know this. This is a collection of theme and incidental music from the ITV schools series Basic Maths (ATV, 1981, Central 1982–86ish) by the Scottish-born experimental musician and composer Ron Geesin. And the only disappointment about this is it led me to see if Ron’s soundtrack for the earlier ITV maths series Leapfrog (ATV, 1978–81) was out on there on streaming. But it isn’t. At least, not yet. I mean, the Leapfrog theme is kind of nightmarish.

WILLIAM HAM BEVAN:

Yeah. We were both at Mumbles Junior Mixed School, though not at the same time. It’s only with the passing of time that I’ve realised how bizarre that school was. Parts of it were absolutely Edwardian – stuff like the teacher blowing a series of four whistles to pipe you in from the schoolyard, like it was a parade ground; segregation of the sexes at playtime; and of course, corporal punishment administered in front of the whole class with a bloody cricket bat. And then in the middle of all that, you’d have the TV wheeled in for these very progressive and whimsical schools programmes. Two that we watched were Starting Science and Basic Maths, and both of those were scored by Ron Geesin.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

Wow, he did Starting Science as well.

WILLIAM HAM BEVAN:

Yes. Starting Science had a track called ‘Twisted Pair’, which has been my ringtone for about the past ten years.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

It’s funny how maths and science schools series in particular seemed to go with classical music for a while and then changed tack. There was a show called Maths Workshop, made before colour came in, but was still being repeated in 1978 with the same theme as Face the Music… you know, ‘Popular Song’ from William Walton’s ‘Façade’. Then there was Maths Topics which had no presenter, all animation, but which had JS Bach’s ‘Badinerie’, which had also been the Picture Book theme in the 50s and 60s. If you go and check these out, they’re immediately recognisable. But then you had this influx of radiophonic electronic output, it was everywhere. And I had assumed that Ron Geesin was part of the Radiophonic Workshop for a while, but he had an entirely different sort of career, as you will probably know. I’d imagine you’re something of a connoisseur of his by now.

WILLIAM HAM BEVAN:

Yeah, though at the time, I don’t know if we even saw the credits of this – the teacher had probably already switched off the television and was wheeling it out of the room on its sturdy metal trolley. But yeah, he was a sort of one-man ITV Radiophonic Workshop. I’ve been following his stuff for a while, he’s not a particularly prolific composer. He’s done a few soundtracks… Sunday Bloody Sunday…

JUSTIN LEWIS:

And also this strange documentary film from 1970 called The Body, about the human body, made by Tony Garnett and Roy Battersby. Geesin did the soundtrack with Roger Waters, who’d been a golfing opponent of Ron’s, apparently, this was just before Geesin helped out on Pink Floyd’s Atom Heart Mother – and it had lots of experimentation on it, to the point where one track, ‘Our Song’, basically consists of lots of fart noises. He put a mic down the toilet pan and it was a pun on ‘stereo panning’. So there you have it.

WILLIAM HAM BEVAN:

I caught him live just before COVID hit, in what he said on stage would be his last ever gig. I think it was the 50th anniversary of the Chapter Arts Centre, in Cardiff. Originally when they were raising money to start Chapter [founded in 1971], he was on the bill at a gala concert at Sophia Gardens. So he came back to Chapter Arts – and it was literally just him on stage with a tack piano and a Steptoe’s yard of other stringed, keyed and skinned instruments. And he just improvised for an hour and a half. I mean, it was absolutely compelling, the most bizarre concert I’ve ever been to. I’ve always bracketed him with Ivor Cutler, probably for no more complicated a reason than ‘they’re both Scottish’. But anyway, at the end, he said – and I’m not going to attempt the accent [let the record state he did not attempt the accent], ‘Well, this is my last gig, because I’ve found doing live concerts now interferes with my bowels too much.’ I don’t know if he’s actually held to that, or if he’s done any more performances since.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

As with 10cc, I do find myself wondering if it’s meant to be funny sometimes.

WILLIAM HAM BEVAN:

Have you read his books?

JUSTIN LEWIS:

There are books?

WILLIAM HAM BEVAN:

He’s produced a two-volume encyclopaedic history of the adjustable spanner. He’s the world authority on the adjustable spanner. And it’s entirely earnest.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

Oh that’s right. I read an interview with him in The Wire. Seems he acquired the collection of the previous world authority on the adjustable spanner after he died.

WILLIAM HAM BEVAN:

But anyway. When I heard that this Basic Maths album existed, there was no question, I was bloody well going to get that. A nice bit of nostalgia, but also a chance to work out if it’s as good or as strange as I recalled. Obviously I’d seen odds and sods of these programmes uploaded on YouTube. But this album… I was blown away. I really think some of it stands comparison with Wendy Carlos and Vangelis.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

There’s loads of ideas in it.

WILLIAM HAM BEVAN:

It’s amazing that all that musical inventiveness and effort went into a TV schools series that must have been produced on a shoestring – animations produced using scissors and sticky-back plastic, and Fred Harris and Mary Waterhouse just talking over a few building blocks and stencilled shapes.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

I find myself thinking of how Look Around You, Robert Popper and Peter Serafinowicz’s schools science pastiche in the early 2000s used their own specially composed music [under the name Gelg] to evoke that early 80s period, but actually the music in this is weirder. And obviously one immediately thinks of things like Boards of Canada…

WILLIAM HAM BEVAN:

Well, I’m not really on board with the whole hauntology trope. I think it’s a really reductive way of looking at things. The idea that everything back in this earlier era was uncanny, eerie… I just don’t think that holds water with Ron Geesin. I find his music very human, very humane if you like, very joyful, very playful. I can’t bracket it with that ‘spirit of dark and lonely water lurking behind you’ or ‘chucking a frisbee into the substation’.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

Yes, I do wonder if public information films have a lot to answer for there. I think some of that is just because the technology was still evolving. Television back then was generally a comforting presence with the proviso that something could come on that might scare the crap out of you, whether an electronic sound or the nightmarish face of a puppet. But that fear could be quite momentary, and then you’d be on to the next thing. I think the reason the hauntology thing took off is that, on television now, everyone’s a bit too keen to be your mate, whereas back in the day, it wasn’t quite that simple.

But one thing I really didn’t know about Geesin… I’d assumed he had a classical background or something, but not at all, seems it was jazz, he was a big Louis Armstrong fan, loved Black American jazz.

WILLIAM HAM BEVAN:

There’s a sort of general ease, a looseness, that’s quite human. A lot of the electronic music I like does colour outside the lines a bit. I think I read in one of the muso mags once that Pet Shop Boys’ ‘West End Girls’ didn’t work until they stopped sequencing the bassline and decided to play it live in the studio. Because the previous versions just didn’t have that feel. It needed that looseness.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

I once heard Brian Eno on some podcast – might have been Adam Buxton’s – saying that he thought Superstition by Stevie Wonder is actually quite sloppily played. But that’s part of the appeal, I think, it means it swings.

WILLIAM HAM BEVAN:

Absolutely. When I listen to 70s Kraftwerk now, which was branded ‘robot music’ at the time, they use things like the Vako Orchestron – actually an electromechanical device, with a spinning playback disk inside it. What stands out is the wow and flutter on it. It’s not precise. It may be a robot, but it’s a very analogue, sloppy robot, with dials and clockwork gears, working to fuzzy tuning signals rather than digital pulses.

—–

ANYTHING: TANGERINE DREAM: Exit (Virgin Records, album, 1981)

Extract: ‘Exit’

JUSTIN LEWIS:

I note this album was released in September 1981, the very same month Basic Maths debuted on television.

WILLIAM HAM BEVAN:

I did not know that!

JUSTIN LEWIS:

So why this one in particular? Because obviously Tangerine Dream has quite a back catalogue.

WILLIAM HAM BEVAN:

Well, two things really. One is perfectly simple. When I get my end-of-year Spotify report, it always tells me this is the album I’ve listened to the most, by a quite extraordinary degree.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

Do you put this on when you’re working?

WILLIAM HAM BEVAN:

Yeah. I find, when I’m working, that I can only listen to familiar music. I can’t do new stuff, particularly if I’m doing close work such as editing. If it’s new music, I end up getting wrapped up in it. But on to the other reason for choosing this. I got into electronic music in the mid-80s – Jean-Michel Jarre first of all, as I mentioned earlier – and it was difficult to know where to go from there. There weren’t other people in school who liked this stuff. So I could take a punt on spending my pocket money on something, but that’d be a gamble.

By chance, my dad worked with someone who was into this kind of thing, and he happened to mention to him once that his son liked Jarre. So this bloke taped the entire Jarre catalogue that I didn’t have – Equinox, Zoolook and Magnetic Fields – plus a Tangerine Dream compilation, which was the first I’d heard of them.

Having got all that, Christmas was coming up, and I went into HMV, looked at all the cassette sleeves of Tangerine Dream albums and wondering which was the best introduction to this group after that compilation. This one, Exit, is the one I chose. And so I got that for Christmas, but that year, I also got a yellow Sony sports Walkman.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

I remember those looked rather stylish at the time!

WILLIAM HAM BEVAN:

Oh, it was amazing. It was the first Walkman to have in-ear headphones. They weren’t like the ear buds you have now – they still had the band that went around the top, but not those horrible foam rubber earpieces that perished into tacky gloop. Instead they had these little discs that went sideways into your lugholes. And the sound was absolutely amazing. I mean, my yardstick at the time was the JVC mono boom box I had in my room, so it didn’t have to clear a particularly high bar, but you know… Christmas morning that year, Tangerine Dream and the yellow Walkman, and when I shoved that tape on, it really was one of those ‘Dorothy lands in Oz’ moments when everything suddenly goes into colour.

But even without the nostalgia kick, I think this is a genuinely great album – it’s the soundtrack to the greatest 80s sci-fi movie never made. At the time, Tangerine Dream had just scored Thief, the Michael Mann film, originally called Violent Streets. That was all right. But it’s a measure of how good Exit is that it’s been used so much for TV and film. Part of it got used in Risky Business, which the group mostly scored using bits of their old albums. More recently, ‘Exit’ cropped up on Stranger Things, and was supposedly a big influence on the original music created for it.

There’s something about this era, the early 80s, that I love. It’s that early digital sound – those really brittle, crunchy tones. One thing you may notice at the start of ‘Kiew Mission’, the first song: it uses the same sound as the start of Michael Jackson’s ‘Beat It’ (released at the end of 1982), which was apparently a stock sound from the Synclavier.

That spell when people were using early digital stuff like the PPG Wave synthesizer, really speaks to me. There’s also Larry Fast, Peter Gabriel’s keyboard player, who made a series of albums under the name of Synergy, and used the Bell Labs digital synthesizer; and Wendy Carlos was making very similar sounds, too. It just evokes this mood I like to wallow in – this sort of dystopic, rainy, neon-lit Middle-European soundscape, although that may just be me projecting Tangerine Dream’s German-ness on to it.

After that, everyone discovers digital systems like the Fairlight and the Synclavier, but they only use them for sampling – why bother laboriously adding up harmonics when you can just sample the sound of someone banging a lampshade? And OK, you do get some fantastic stuff out of that avenue, like Jarre’s Zoolook and the Art of Noise. And Yamaha launches the DX7 [in 1983] with its wipe-clean digital sounds, and that took over pop as we knew it. Suddenly everything sounded like a DX7.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

Where would you suggest people start with Tangerine Dream if they’re unfamiliar with the oeuvre?

WILLIAM HAM BEVAN:

Well, 80s Tangerine Dream is very different from their 70s stuff, and it’s dictated by the technology. I wouldn’t start with the earliest albums, on the Ohr label in Germany. They’re quite hardcore. The start of their period on Virgin Records, 1974, you’ve got albums like Phaedra and Rubycon, dictated by these sequencers that can only play eight or sixteen notes, so you get these repetitive, hypnotic pieces. Gradually they became more melodic and then, the turn of the 80s, there’s a revolution in the technology. Until around 1980, I think, most of their concerts were almost entirely improvised. After that, you get whole 40-minute suites that are pre-programmed.

Both 70s and early 80s Tangerine Dream throws up some fantastic stuff. But I suppose the golden rule is this: don’t listen to anything they did after 1986. That’s when they became terrible – what you’d now call a new age group. There’s one interesting thing around that time, one of the big what-ifs: they very nearly did the Miami Vice soundtrack, and they only didn’t because they’d already signed up to do Street Hawk [which lasted just 14 episodes in 1985]. I wonder if Miami Vice would have had an entirely different feel had it been scored by Tangerine Dream rather than Jan Hammer? And would [Tangerine Dream frontman] Edgar Froese have ended up on a NatWest advert?

—-

WILLIAM HAM BEVAN:

I’m hugely grateful to Mum and Dad for this idea that there should be no barriers to entry with music. If you hear something you like, get it. I can visualise the stack of tapes in the kitchen, and there’d be Jacqueline du Pre, Enya, John Cougar Mellencamp, Gershwin… as you said, all the food groups. There was one episode of [the eclectic BBC2 music programme] Rapido that I watched with Mum – she liked Voix Bulgares, the Bulgarian choir, and I liked Front 242, and we both bought the albums. Dad, who’s now 88, got into Propaganda and Frankie Goes to Hollywood in his retirement.

One other thing sticks in my mind. I remember playing Depeche Mode’s Violator in the car shortly after it came out, 1990. We were driving through France, and Dad said, I like this because it reminds me of The Moody Blues. Not a link I would ever have made, but I realised after a while that he was absolutely right: some of the production flourishes are a dead ringer for Moody Blues at the height of their prog era.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

I wonder if the song was ‘Sweetest Perfection’ because the rhythms in the vocal line are exactly ‘Nights in White Satin’.

WILLIAM HAM BEVAN:

You’re right! And listen to the orchestral segues in ‘I’m Just a Singer in a Rock and Roll Band’ next to ‘World in My Eyes’ – or compare the endings of ‘Legend of a Mind’ and ‘Policy of Truth’. What Alan Wilder was doing with millions’ worth of digital sound technology, Mike Pinder had managed by twiddling the tape-speed knob on a Mellotron.

Incidentally, Mum’s phrase when I was listening to slightly more challenging music in my teenage years… if I put something like Einstürzende Neubaten on the downstairs stereo, Mum would poke her head round the door and say, ‘Can you put something on that we can all enjoy?’ For all my parents’ open-mindedness, there were limits, and the sound of a load of half-naked Germans banging the walls of an underpass crossed the line for them. I suppose we all have our red lines.

—–

William now looks after the content agency Flong (www.flong.wales), providing editorial services for creative studios, businesses, universities and public bodies.

You can follow William on Bluesky at @hambevan.bsky.social.

—-

FLA 31 PLAYLIST

William Ham Bevan

(For the time being, this site and project uses Spotify for the conversation playlists, but obviously I disapprove that Spotify doesn’t pay artists and composers properly, and other streaming platforms are available, as are sites to buy downloads and buy recordings. For consistency, you can also listen to the selections via YouTube (where available), and links are provided in each case, below.)

Thanks to Tune My Music, you can also transfer this playlist to the platform or site of your choice by using this link: https://www.tunemymusic.com/share/BWo1ohOiiF

Track 1:

PUSSYCAT: ‘Mississippi’: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=eGL07TLQ5hM&list=RDeGL07TLQ5hM&start_radio=1

Track 2:

NEW ORDER: ‘The Perfect Kiss (12” Version)’: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=l_12gjuysec&list=RDl_12gjuysec&start_radio=1

Track 3:

RAH BAND: ‘The Crunch’: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hIxnshqW84c&list=RDhIxnshqW84c&start_radio=1

Track 4:

JEAN-MICHEL JARRE: ‘Oxygène, Part 4’: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_PycXs9LpEM&list=RD_PycXs9LpEM&start_radio=1

Track 5:

SPACE: ‘Magic Fly’: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TONnzySDbqk&list=RDTONnzySDbqk&start_radio=1

Track 6:

10cc: ‘Une Nuit a Paris (Part 1)’ / ‘The Same Night in Paris (Part 2)’ / ‘Later The Same Night in Paris (Part 3)’: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Dc7drqD4RtI&list=RDDc7drqD4RtI&start_radio=1

Track 7:

10cc: ‘Old Wild Men’: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4it5yrI1MsA&list=OLAK5uy_ludkI5Lr35_6CwakMigXibZnBmgjyLVM8&index=4

Track 8:

10cc: ‘Somewhere in Hollywood’: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GW76HfE_zm0&list=OLAK5uy_ludkI5Lr35_6CwakMigXibZnBmgjyLVM8&index=7

Track 9:

RON GEESIN: ‘Welcome to Mathematics’: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=395GMpPlmME&list=RD395GMpPlmME&start_radio=1

Track 10:

RON GEESIN: ‘Soft Mirors’: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0zL__7YW_cU&list=RD0zL__7YW_cU&start_radio=1

Track 11:

RON GEESIN: ‘Twisted Pair’: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ISDv0hLGmjk&list=RDISDv0hLGmjk&start_radio=1

Track 12:

TANGERINE DREAM: ‘Exit’: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UCPF_4eJJME&list=RDUCPF_4eJJME&start_radio=1

Track 13:

TANGERINE DREAM: ‘Network 23’: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vyyq83h4808&list=RDvyyq83h4808&start_radio=1

Track 14:

THE MOODY BLUES: ‘I’m Just a Singer (in a Rock and Roll Band)’: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5Xvr5l8s4YY&list=RD5Xvr5l8s4YY&start_radio=1

Track 15:

DEPECHE MODE: ‘World in My Eyes’: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XY3e46pf03Y&list=RDXY3e46pf03Y&start_radio=1

Track 16:

EINSTÜRZENDE NEUBATEN: ‘Sehnsucht’: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cOk_8foS0BM&list=RDcOk_8foS0BM&start_radio=1