Shanine Salmon, a lively, knowledgeable and funny writer, quizzer, quiz question writer, theatregoer and theatre reviewer, is another friend I knew I wanted for First Last Anything. We were both on internet forums for years before we actually met, about 15 years ago. She is the very first person who ever commissioned me to do an art birthday card – this was in 2017 when I’d just started doing the When is Births daily birthday card series on the internet, and so began an intermittently profitable sideline project. Thank you, Shanine.

When Shanine and I spoke, via Zoom, one evening in August 2025, it had been a while since we’d had a proper chat, and so what follows has been carefully extracted from a three-hour gossipy ramble about what we’d both been up to lately. Expect some thoughts on Michael Jackson compilations and biopics, nepotism, quizzing and expanding one’s knowledge, and finally, the thorny and timely topic of AI-generated music, and whether or not it’s easy to spot. We hope you enjoy our conversation.

—-

JUSTIN LEWIS:

So tell me about your earliest memories of music and what you first remember hearing at home. It can be anything, anything at all.

SHANINE SALMON:

Apparently, as a baby toddler, in the late 80s, my mum would play vinyl records, because I’m quite old now. And I used to cry, I wasn’t someone who was naturally musical, apparently. The first album I remember listening to, on a loop, and feeling, ‘I want to listen to this’ was a NOW album, NOW 25, released in 1993. My mum was really shocked at how much suddenly I was into music, and I don’t think I was into anyone specifically. I just liked listening to that NOW album. It had the remix of Freddie Mercury’s ‘Living on My Own’ on it [which was a number one single the same month, August 1993]. And then certainly later, we had things like The Box [cable music TV channel 1992–2019], so that’s how I would get a lot of my new music, and then obviously through radio.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

In this run of FLA, I seem to have got guests born in the 80s, and what I realise is how many of them in their formative years saw TV channels continuously full of music videos. And that is the big difference between what I grew up with, where you would have pop programmes and you might see a video, but you didn’t see videos round the clock – you still had to listen to the radio. Did you have Sky or something like that?

SHANINE SALMON:

We had cable, which I don’t think we could afford! I feel like if it was MTV… my memories of MTV were then they started to move into programming rather than just videos. VH1, similarly – I got asked a question in a quiz: ‘Who sang “Love and Pride”?’, and because as a small child, I’d seen Paul King being a VH1 presenter, I couldn’t believe it was the same man. He was still a good-looking man, but he was so different to when he’d been in King 10 years earlier. Being ancient now, we’re losing that visual medium. One of the reasons I probably struggle to keep up with new music is I don’t have that visual reference.

And I stopped listening to the radio quite early on in my life – in my twenties when I felt that Radio 1 was just unlistenable. I had been big on my boy and girl bands. But I felt I lost touch with music when I had to start working full-time, in 2011. I was doing the sorts of job where you wouldn’t have the radio on. I think if my career had taken a different path and I had other sorts of job, maybe I would still listen. It was just really hard to access – and equally, smartphones were just coming out. I think I had iTunes and those kinds of things, but it was very difficult to work out ‘What is new out there?’ And keeping up with it, as well as doing an eight-hour day of work or whatever.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

It felt like around 2010, 2011, there was a bit of a dip, it felt like there wasn’t a lot going on.

SHANINE SALMON:

There wasn’t really. It was peak X Factor [era], so it took me a long time to really appreciate someone like One Direction, by which time they’d long broken up, and there was actually good stuff like Little Mix. So it wasn’t me consciously going against those since I was watching those programmes, but what X Factor released was usually quite dirgey and boring. And that would dominate Christmas.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

Well the Christmas charts are terrible now.

SHANINE SALMON:

Oh, who even cares?

JUSTIN LEWIS:

It’s the only time anybody looks at what’s number one anymore.

SHANINE SALMON:

It all went wrong [in 2015] when they moved the Sunday chart show, which I was obsessed with, to Fridays. Every Sunday it had been the proper countdown, and you didn’t know till the end what was number one. And when it moved to Fridays… There aren’t big shocks anymore.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

All the tension’s gone, hasn’t it?

SHANINE SALMON:

This is it. It’s not exciting to even listen to music, let alone buy music. I write quiz questions now, and if you’re going to contribute to writing quiz questions about music, to do ‘so and so charted’ – who cares? That isn’t how music works.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

When I was in my teens in the 1980s, at school, I would take in my tiny little portable radio on a Tuesday and at Tuesday lunchtime, just before one o’clock, Gary Davies on Radio 1 would announce the new Top 40. He’d play number 5, 4, 3, 2, then he’d count down the whole top 40 towards number one and would play the new number one. Which was really exciting, though it sounds ridiculous at this distance to say that now, but it seemed to mean everything at the time.

SHANINE SALMON:

You wouldn’t get a Blur/Oasis type war now.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

No, I don’t think you would.

—–

FIRST: MICHAEL JACKSON: HIStory: Past, Present & Future, Book I (Epic Records, double album, 1995)

Extract: ‘Off the Wall’

JUSTIN LEWIS:

I’m gonna ask you now about the first record you bought.

SHANINE SALMON:

Yes – this was not with my own money, but I chose it. It’s the double cassette of Michael Jackson’s HIStory, which was a combination of a ‘best of’ on the first cassette, and new stuff on the second…

JUSTIN LEWIS:

Which was officially called ‘HIStory Continues’, which I didn’t know at the time.

SHANINE SALMON:

No, I didn’t realise that. I just knew the good stuff was on tape one, and then… tape two, it’s alright.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

So it was the hits you went for?

SHANINE SALMON:

I think it was the hits, because my mum had Off the Wall, which is still as good as Thriller and Bad are. Yeah – Off the Wall is the one I still go back to. Particularly the single of ‘Off the Wall’- a sign of what he was capable of. And yeah, HIStory obviously comes at a weird time. It’s post-allegations, and so the second cassette is songs about that, so that isn’t fun to listen to even now, whereas the old stuff [is].

Just in the last few days, they’ve been talking about this Michael Jackson biopic [Michael] that was due to come out this year. It’s been delayed. It’s starring Jaafar Jackson, one of his nephews, as him, but while Michael Jackson is long dead, his estate are still controlling what is and isn’t said. But it’s going to be a four-hour film, right, which is insane, and they might have to split it into two films. But this isn’t like the Wicked film – I went to see it, didn’t think it was that good – but you have to see the second part of it to conclude it. But why would you go back to see a second part of this where you know what happened: he dies in the end, and he doesn’t get any justice and the people that accused him don’t get any justice.

In any case, you’ve already got Michael Jackson biopics, both good and bad. You’ve got The American Dream, the TV miniseries with the Queen of Music Biopic, Angela Bassett, which is what this sounds like, but not as good. Like, why would you do that? And then there’s a terrible one called Man in the Mirror (2004), made while he was still alive, which I watched years ago and then watched again in lockdown as apart of a Friday film flop group watch I was part of – one of the most cheaply made films that you will ever see.

But yeah, as a child, I used to be really scared of Michael Jackson, when I was about four or five, because there was a big gap, a scary four-year gap between Bad and Dangerous. When he came out with Dangerous, particularly the ‘Black and White’ video, he obviously got older, but he looked like a different, odd man.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

Also, the album titles get more and more extreme. So you’ve got Thriller – though it should really be called ‘Horror’ if you’ve got Vincent Price on it – then Bad, then Dangerous. What’s the next album going to be called? ‘Monstrous’?

SHANINE SALMON:

Yeah, he goes back to that theme with the final album, Invincible.

JUSTIN LEWIS

But I was listening to the second disc of HIStory, ‘HIStory Continues’, and realising how angry a lot of his records are. Even the really good ones.

SHANINE SALMON:

Yeah, the anger on ‘Scream’ works, because I think it’s a really good track with Janet. And the excitement, which you wouldn’t get now, about its music video – which doesn’t look that expensive but I think was the most expensive at the time. And him and Janet hadn’t duetted before, they’d had quite separate careers.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

Apart from… Janet’s on ‘P.Y.T.’, on Thriller. She’s one of the backing singers.

SHANINE SALMON:

But yeah, the anger on this record. ‘DS’, which is an attack on one of the attorneys and he’s changed the name very slightly. I think that’s as bad as it gets, and if you don’t really know who that man is, or anything about the allegations… yeah, the whole thing is very angry. It’s very righteous. Like, ‘Earth Song’’s awful.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

I’m quite relieved you’ve said that! [Laughter]

SHANINE SALMON:

It’s the worst song, not just the worst Michael Jackson song. But I quite like ‘Tabloid Junkie’, but it’s quite similar to stuff he’d done earlier, so a bit like ‘Price of Fame’ [originally intended for Bad] and ‘Leave Me Alone’ [which was on Bad]. That kind of vibe. But had he still been alive now, even after the Leaving Neverland documentary, that absolutely would not have been the end of him. It couldn’t have afforded to have been the end of him, but he wouldn’t have been making new music. He would still have been, I think, a big global star, he might have retreated a bit or just toured and hoped for the best.

But with HIStory, the ‘best of’ bit is great, the best of that period – but the second disc feels quite dated for 94, even in hindsight. Somebody said he was not working with the most up-to-date rappers. I think the Notorious B.I.G. is on one of the tracks. But then there’s things like the cover of Charlie Chaplin’s’ Smile’.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

Which he’d been talking about doing for years. And the cover of ‘Come Together’ – which had been in the vault for years [since 1986], and was that just because he owned the copyright for all the Lennon/McCartney songs at the time?

SHANINE SALMON:

I go back to the odd song: ‘They Don’t Care About Us’… ‘Stranger in Moscow’, actually. Recently, I’ve actually been listening more to some tracks from Blood on the Dance Floor, the remix album which grew out of tracks from HIStory.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

Were you buying singles as well at this time?

SHANINE SALMON:

After this, yeah. I remember going to Woolworths and buying ‘Slam Dunk (Da Funk)’ by Five. But I also had Backstreet’s Back by Backstreet Boys, the whole album. It was like peak-boyband era.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

Do you still regard that 90s pop period fondly? Have you read Michael Cragg’s book [Reach for the Stars]?

SHANINE SALMON:

Oh the one about S Club 7 and so on? That’s a really nice oral history, the best way to do it because most of the people involved are still alive. Rather than a book where it’s him coming at a ‘fan angle’. There’s lots of people being very shady and bitter – and you realise what a horrible time it was. Did you see the Boyzone documentary?

JUSTIN LEWIS:

I haven’t yet. I believe Louis Walsh comes out of it badly.

SHANINE SALMON:

It’s incredibly evil. These poor young men and the Stephen Gately story has this obvious tragedy to it, but even if he was still alive, it would still be really sad. They didn’t get on, they were kind of manipulated, and it’s not unique to Boyzone. Only now do I think we’re at a point where we knew this kind of stuff happened, and we’re willing to talk. The music is very nostalgic, but digging deeper, you realise there’s a lot of sadness and manipulation and abuse, and all sorts of things that were happening to get those songs out there.

——-

LAST: PHOENIX: Wolfgang Amadeus Phoenix (Ghettoblaster SARL, album, 2009)

Extract: ‘1901’

JUSTIN LEWIS:

Let’s move on to something that probably hasn’t got any allegations attached to it.

SHANINE SALMON:

Well, you say that – but Phoenix controversially, though it wasn’t controversial at the time – released an album in 2013 called Bankrupt, and they did the Coachella Festival, and they brought on R Kelly…

JUSTIN LEWIS:

Oh god.

SHANINE SALMON:

Performing a version of ‘Ignition’. And this was 2013, 2014, so people already knew about R Kelly and the allegations. And they said, ‘Oh, it’s all been disproven’ – and then obviously the Surviving R Kelly series came out (2019–23) and they had to release a statement saying, ‘Actually, sorry, we were wrong.’ So, all my music choices are fuelled by R Kelly’s base controversy.

But anyway, Phoenix. Adam Buxton used to host a thing called Bug [series of live events, which became a TV series for Sky], which was like a presentation of music videos – and that’s how I got into Phoenix, because he played the video for ‘Trying to Be Cool’, which came from Bankrupt. Which I thought was really good. I got into them, and then didn’t listen to them for years, but then got back into them just after their last album, Alpha Zulu (2022). I went to see them at Brixton Academy about two weeks before there was a horrible crush there, and so it closed for about a year.

But yeah, they’re French, French touch, they’re same era as Air. The guitarist Lauren Brancowitz used to be in a band with the future members of Daft Punk, called Darlin’ – and the review that Darlin’ got [‘a daft punky thrash’, a live review in Melody Maker] is how Daft Punk got their name.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

Doing the research for this, I discovered one of my favourite Air songs has Thomas Mars from Phoenix on it: ‘Playground Love’ [from The Virgin Suicides soundtrack]. I somehow had no idea that was him. Because it doesn’t sound like him singing at all.

SHANINE SALMON:

He’s not credited as Thomas Mars, is he? He’s called ‘Gordon Tracks’. I know my Phoenix! So anyway, I’ve got obsessed with them again, last couple of years, but they’ve been going a long time. United the first album was released in 2000.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

Some of their songs have enormous streaming stats, especially things off Wolfgang Amadeus Phoenix (2009).

SHANINE SALMON:

Yeah, which won the Grammy. ‘1901’, you don’t necessarily know it by that title, but you’ve probably heard it because it appears in Friday Night Dinner, quite randomly.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

That does show up a lot in that.

SHANINE SALMON:

That’s probably still my favourite album by them, but it takes me a while to get into their albums. There’s one album of theirs I didn’t like, and now I listen to a lot of songs from it. There’s still stuff of theirs I need to explore because they’ve got this big back catalogue.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

Feels quite exciting, though, when you discover a new band and they’ve done all this stuff you’ve never heard.

SHANINE SALMON:

And you realise they’re not that young anymore, but it doesn’t feel tired. They haven’t got some kind of weird Rolling Stones reputation. The Rolling Stones to me always seemed ancient. There’s a sense of tragicness to the Rolling Stones trying to stay relevant – whereas with Phoenix, I don’t know if it’s because they’re not British or American, but they’ve got this sort of ageless quality, it doesn’t sound like the stuff of old men, though I think they’re all 50, or approaching it.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

I think when people start out in bands now, and they’re taking it remotely seriously, they have to think in terms of a career. It’s hard to imagine the Rolling Stones starting and thinking, ‘We’re still going to be doing this in twenty years.’ Let alone sixty. Nobody could have guessed what rock’n’roll would become. Not even The Beatles could have dreamt of where they would get to, whereas now because they’ve seen what those groups have done, the triumphs and the mistakes, and they think, ‘Okay, how can we live our lives, and stay alive’ – which helps, but also doing other interesting things, maybe taking a break sometimes.

SHANINE SALMON:

There’s that joke in The Simpsons in the 90s when Lisa’s getting married, and it’s set ‘in the future’ in 2010 and the Stones are still touring, and it’s called the Steel Wheelchair Tour. But you’re saying about musicians taking a break. You’ve got a situation where Taylor Swift and Beyoncé are like throwing out albums, throwing out music, and that’s obviously how they like to work. But Phoenix are genuinely exciting, because they have at least a couple of years, if not four or five, between albums. There isn’t this kind of churning out with them. The next album, if they do one, will be their eighth, which is nothing, you know.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

They seem to be doing singles at the moment, or collaborations, remixes.

SHANINE SALMON:

Yes, they released ‘Odyssey’ with Beck, but they’re meant to be doing something with Lil Nas X in the studio. But I’ve never really been that involved in the fandom of waiting for an album, and despite following them sort of on and off for twelve years, this is the first time I’ve been wondering, ‘When’s the next album coming?’

And this leads me on – though she doesn’t sound anything like Phoenix – to Romy Mars, who’s Thomas Mars’ daughter, he’s had two daughters with Sofia Coppola. Romy Mars is this TikTok star nepo baby now, she’s good pedigree for a nepo baby because she’s related to Nicolas Cage, her father’s this musician… she’s related to everybody. She came to fame with this TikTok clip where she’d been grounded after trying to use her parents’ credit card to charter a helicopter for a friend. So it was this weird sketch, she was saying ‘Come and make vodka pasta sauce with me’, she’s got her babysitter’s boyfriend there. She says to him, ‘Do you remember the helicopter fiasco?’ and he’s like, ‘Do you mean “fiasca”?’ because it’s like ‘feminine’ – it’s really odd. It feels like she’s going to be like her mum and wants to direct films.

But then, maybe end of last year, she released her first single, I think she’s released four now. And even though I can’t relate to this 18-year-old nepo baby who’s clearly incredibly rich, it’s surprisingly good stuff. I think I like it because she’s clearly taking a lot of influence from her dad, vocally. And obviously there’s talk about how, to get into the music industry, you have to have a parent… all these gazillionaire parents who are funding studio time for their kids. She isn’t really doing much with her dad, though, as far as I know, she’s writing her own stuff.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

Yes, it’s quite good. She probably stood more of a chance with the work being good than, say, Brooklyn Beckham. Can you imagine if he’s got an album lined up? I guess that’s the point – it’s not just about having talented parents, it’s about having a particular vision. No disrespect to Victoria Beckham, who’s obviously become incredibly successful. And anyway, it’s not like the offspring of rich, famous people make uniformly terrible stuff. It doesn’t work like that – sure, they’ve got those connections, but they can actually do it as well.

SHANINE SALMON:

And historically, you would probably go into a field that your parent has been in, so you wouldn’t judge someone who was a doctor and whose dad had been a doctor. I’m not really sure how I ended up in the field I work in, but my mum didn’t really work, and I didn’t really know what jobs existed and how you got into them. It’s such a privilege to have that connection, that knowledge, to know you need to go to university and get these A levels, or do that apprenticeship… whatever it is. You only get that with knowledge, and I think younger people now have more access to that sort of knowledge: ‘I know “so and so” is a job. How do I get into that?’

I think it’s the nepo babies that don’t realise they’ve got the privilege, or play it down with, ‘Oh no, I’d have still been here.’ No you wouldn’t, because you wouldn’t have that knowledge! And you wouldn’t have had the money and time spent on you getting to the standard you are at. Even just being able to play an instrument. I don’t know how it is at schools now, but I started playing one, and then didn’t really finish it off. Where do you get that support, particularly when state schools don’t have the money to support and develop an interest or a talent. It wouldn’t surprise me if there are schools that don’t have music, or drama, or art.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

They’re just considered luxuries by some.

SHANINE SALMON:

They’re absolutely not, but we’re already seeing it through the drama school system. The top drama schools, it’s all probably going to be people who went to private schools that are able to do drama exams. I used to work at Trinity College London, administering the drama exams, and the majority were all private schools. There’d be the odd state school, and they’d get very excited about that, but that was because they were like one of two or three. The rest were all private school, or self-taught people. But I started that job over a decade ago, and at the time, I thought, ‘This is why you’ve got a situation where so many actors have been to Eton.’ There was a quizzing tournament against people who were in quizzing but who happened to be teachers, and one of the teachers worked at Eton, and they were all talking about how they had these inter-school competitions. So yeah, that’s still common. If you go to public school or private school, suddenly there are these opportunities because parents are happy to pay the school fees for the extra-curricular stuff.

But, like anything, you have to start people young. Take languages, in terms of learning languages, this country is a disgrace. The only way for most people to pick up multiple languages is that they’re in a household with them, because they heard it from birth. We should be teaching languages from the moment children enter the nursery, or infant school at the latest. To leave it till eleven or twelve like I had it is too late, unless you’re only going to be teaching me entirely in French.

But that’s why you’ve got the situation in the music industry where it feels like it’s dominated by people with privilege, and while it’s not impossible for those without those connections, it would take them a lot longer, and lots of talented people don’t make it. There’s no guarantee that you’re going to be found.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

When they opened the Brit School in 1990, one of the big ideas was that talent would be nurtured, but while it’s true that some very talented people have come out of it, the records all sound the same. I mean, some of them are fine, very accomplished.

SHANINE SALMON:

Yeah, Brit school is interesting. It’s in a really awkward bit of Croydon, in fact it’s Selhurst. It’s so hard to get to. But you have to be in or near London, which I’m going to say is a privilege. London is expensive. There was a story where someone I can’t with the context that someone had moved down from.the North of England so their child could attend the Brit School. Again, that’s privilege. So, even though on paper, ‘it’s accessible to everyone as long as they audition, and they’re very good’, it’s still London, and their parents still have to make sacrifices. And how many parents do they have?

—-

JUSTIN LEWIS:

I sort of know the answer to this, but I’ve sort of forgotten. How did you get into quizzing? Because you’ve appeared on a lot of TV quizzes. What was the first one you did?

SHANINE SALMON:

The first one I did was in the summer of 2007. It was National Lottery Jet Set, on BBC1, hosted by Eamonn Holmes. I have a picture – where I argue I look exactly the same even though I was 19 and I’m not anymore – of Eamonn Holmes standing behind me in a slightly menacing fashion, with his arms on my shoulders. And I post that whenever, inevitably, he does something ridiculous.

How did I get into it? I didn’t really watch game shows – I don’t really watch them now. I just like reading and knowing stuff, and the pressure of having to pull the answer out quickly. There’s no fun for me in having all the time in the world to answer the question because most people can do that. Oh, and you can win money, that was always attractive!

I’m not good at crosswords. No word puzzles, I’ve been doing the one on LinkedIn called Cross Climb, I quite like that. But I could never do Countdown. What interests me is general knowledge, and particular areas that I’m interested in. I’ve always been bad at science and geography, from school, and didn’t pick up any interest in them as an adult.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

And your degree is history, is that right?

SHANINE SALMON:

History degree, very modern history. But between 2014 and 2021, I didn’t do quizzes, and I’m not sure why. I was doing a lot of temp work, and taking time off work would have been really difficult. And also I was going to the theatre a lot, which I wasn’t making any money from, but it was a big hobby, and still an area of interest.

But with recent quizzing, this came about in December 2019, just before everything went weird. Oliver Levy, who’s married to Paul Sinha, had been trying to get me into quizzing for years, and I was like, No, it’s for professionals. And the quizzing was always at weird locations, and I was quite a lazy person so I didn’t bother going! [Laughs] But people kept saying to me, ‘There’s not really many women in quiz, come along and join it’. So I agreed that when I got home, I’d sign up for the Summer Friendly League. And then obviously I forgot about it, but I was doing a lot of quizzes with friends during lockdown, and then finally during summer 2020, the Summer Friendly League of Quiz of London went online. So as with everything else at the time, I was doing it from my living room or bedroom. And I’ve been in the quiz community ever since, I’m on the Quiz of London Committee now. I do a lot of question writing.

And I started going on television again. The first thing I did was The Tournament [BBC2, hosted by Alex Scott] in 2021. In the first episode they’d ever recorded of it. It’s the only TV quiz I’ve won, and it still gets repeated – so everyone will tell me now that my episode is on again because I win. It was nice to win, but with television I’ve not had much luck. I’ve come close, but I’ve not won anything since.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

Would you agree it’s actually quite difficult to win TV quizzes, because it’s not just about knowing the answers, it’s about the strategy of whatever the format for that quiz is. You can’t always know in advance what strategies you’ve got to employ.

SHANINE SALMON:

Because of the quizzing I do, I don’t feel relieved if I recognise other players, or if I don’t recognise other players. Just because I don’t know them doesn’t mean they’re not better than me. And that’s what I’ve often had. There are people you’ve never come across before who are not in the quiz community, but are very naturally bright and intelligent and are probably doing lots of quizzing. So I agree – it’s very tough. There are all sorts of other circumstances. They’re very long days. I’m not a morning person, so if I have to get up at 7am for a briefing. You’re often in a hotel – most of the game shows are filmed outside London now, places like Belfast, Glasgow. But certainly in terms of competition and other factors, you can’t control those.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

They’re like job interviews, really!

SHANINE SALMON:

They are! And the whole process of just getting on them in the first place. The last one I did of these was Jeopardy with Stephen Fry [in September 2024]. I’ve done a couple of radio quizzes, last few years. I did Brain of Britain and also Counterpoint [Radio 4 music quiz].

JUSTIN LEWIS:

Remind me, did you get to the final of Counterpoint?

SHANINE SALMON:

I got to the semi-final, same with Brain of Britain. I managed in both cases to win my first heat, both of them a shock. I’m very good at thinking, ‘Oh who cares, it’s just a heat’ with quizzes. But at semi-final, I think, ‘Oh this is serious’ and then I sort of fall apart. With Counterpoint, I did read some classical music books, but they didn’t help me! But I’m not too bothered about those ones, cause there’s no money.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

There’s a trophy.

SHANINE SALMON:

But I’m always willing to try out a new quiz format. I’ve participated in development run-throughs [quizzes broadcasters are piloting to see if they work]. Development run-throughs are great if you want to do a game show but you don’t want to be on television and they pay you like £50 for three hours to see if the show works. I get on run-throughs a lot, because I’m great to have in front of a TV commissioner, who will think: ‘She’s a woman, she’s not white, she knows how to talk to people…’

JUSTIN LEWIS:

You don’t freeze on camera or under pressure.

SHANINE SALMON:

As much as I consider myself an introvert, I’m happy to talk, I’m great at having to run through, and I behave myself. And I’m always happy to give feedback, good or bad. But they’re so desperate for women on quizzes – I think that’s why Jenny Ryan [on The Chase] and Beth Webster [on Eggheads] and a few others have been rewarded because they were there when there were hardly any women. When you go to quiz events, there’s a lot more now.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

Do you have particular strategies you’re prepared to share about how to improve? What advice would you give to anyone wanting to get into this?

SHANINE SALMON:

It depends on how you learn. If you enjoy reading, there’s no shame. I am a history person, I’m a lifestyle person, I like sport. In a team quiz, that’s going to be really useful. So don’t feel you need to learn everything, but I would say, learn your level 1s, your easy science if you find it incredibly boring like I do. That stuff is going to stick, and that stuff is going to keep coming up – and it’s the stuff you should vaguely know anyway. But I don’t really have any personal tips. If you enjoy a hobby, you will get better at it, perhaps, but you can only do that by getting into it in the first place, and then hearing lots of different questions and different formats.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

From about 18 to 21, I worked in a record shop which tended towards heavy metal. It didn’t exclusively stock that, it did some indie, and a bit of dance, and we were on the panel of shops for the BBC Radio 1 and Top of the Pops chart. But I realised I would very quickly have to get more knowledgeable about it, as I wasn’t particularly a fan. You’d have to be vaguely on top of it, so I’d read Kerrang! every week, and gradually you’d work out who customers were asking for. It’s surprising how much of that has stuck in the memory. It’s not always just about what you already know, and it’s certainly not always about what you like.

SHANINE SALMON:

Yeah, for me it’s about lived experience. That’s far more exciting than having heard a question a million times before, or having read a book.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

Our mutual friend Simon Scott interviewed you once, and you were talking about how quizzing was finally adapting beyond the world of mainly white men, both in representation and in subject matter. Is that still improving?

SHANINE SALMON:

The league quizzing is still dominated by older white middle-class writers and edited by older white middle-class writers. So, as a result of going, ‘You can’t beat them, join them’, I’m learning that stuff, and then improving as a result. Television, I don’t know because I don’t watch as much television, but in my experience, beyond Tipping Point, most of the quiz shows are getting much harder. Pointless is harder. The Finish Line, when I did the second series, was much harder. Jeopardy was tough, but Jeopardy is always tough. The questions in that were pretty diverse, but there was stuff that suited me, like quite modern television, like The Wire. You wouldn’t really get that in a lot of daytime shows.

But yeah, you don’t see that much diversity in quiz casting. There was Dave Rainford on Eggheads, but he died. There’s Shaun Wallace and Paul Sinha on The Chase. Even with hosts now, Clive Myrie’s probably the biggest one, on Mastermind, there’s Amol Rajan on University Challenge, but both of those took the old white men to go, ‘I don’t want to do this anymore’ for them to make that change, they wouldn’t have willingly done that otherwise.

But where are the new formats? And then where are the new contestants? I do a lot of league quizzes that are based in India, where obviously Indian people are the majority. But there isn’t a racial barrier to quizzing – there shouldn’t be. I would say the biggest barrier is about where your parents are from. You have a lot of people who are white British passing, but actually, if your parents grew up in America, or Australia or any other places with their own cultures, they’re going to pass that on to you. You very rarely hear people saying, ‘My mum is why I’m in quizzing.’ Men and women always say, ‘Me and my dad would watch stuff together.’

There’s still this male dominance there. The non-white side is improving. But I whenever I try and kind of expand the canon with questions, it’s met with ‘What the hell is this?’ There was one I wrote: ‘What was the first film that Vincent Minnelli directed?’ And I paired that question with the title of another film, one that shared its title with a song. Both films from 1943.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

This feels like something I should know.

SHANINE SALMON:

It feels like you should? It’s Cabin in the Sky, 1943. It’s a Lena Horne film, it had Bill Robinson in, Cab Calloway, Fats Waller. It’s Minnelli’s first feature film, but it’s also the first feature film with an all-Black cast. So I think that’s quite notable. But it’s old cinema, there were a lot of things that made it a tough question. But you expand it by saying ‘There’s two notable films, and the other one was called Stormy Weather, which ties in with the song of the same name.’

JUSTIN LEWIS:

I suppose there’s the option to reverse the question. ‘Cabin in the Sky was the first feature film directed by who?’

SHANINE SALMON:

Yeah, but then you make the white man the answer!

JUSTIN LEWIS:

Oh god, how embarrassing is that. [Laughter] I just wasn’t thinking at all, there. Totally fell into the trap.

SHANINE SALMON:

And this is what keeps happening.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

I’m going to leave this in, to embarrass myself. [Laughter] Because it’s quite revealing, isn’t it?

SHANINE SALMON:

Because it’s not on your radar. Why would you want to watch this all-Black cast in a 1943 musical film?

JUSTIN LEWIS:

But what’s also shocked me about this is that I didn’t know the name of the film.

SHANINE SALMON:

Stormy Weather was a slightly easier question, because of the song, and Etta James had recorded it. So sometimes with a Level 4 question I do try and soften it a bit. But yeah, these are two films with an all-African-American cast released in 1943. That to me is notable at that time because obviously you’ve got segregation, and ‘Who was this film for?’, during wartime. So it’s a really interesting question.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

Was Carmen Jones around the same time? Or was that a couple of years later?

SHANINE SALMON:

[Checks] 1954. But that was the film. The stage musical was 1943. The musical’s around. But yeah, there’s this idea – and this is not a non-white or racial thing – this term we use called Ins for Him, questions about women’s interests, or things that women are going to be interested in. Make-up is a top subject, fashion – women-led hobbies etc, I’m loathe to say it, because of course men wear make-up! It’s a ridiculous thing to say. But you get round it by adding in a clue, so something like ‘This person shares their name with this sportsperson that you like’.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

So you embellish the question.

SHANINE SALMON:

You embellish the question, to focus it on the thing that the man might know.

——

ANYTHING: Mc JHEY AND BLOW RECORDS: ‘Predador de Perereca’ (2025, Blow Records)

JUSTIN LEWIS:

I am still relatively ignorant on the issue of AI music. So were you consciously looking for this, or did this come looking for you?

SHANINE SALMON:

I don’t think I was aware of how prevalent it is. I still think I’m probably quite naive. But when you messaged me for this, asking, ‘What do you want to talk about, what’s interesting you at the moment?’, I thought of this, because this song is on my ‘liked songs’ list, which currently has 927 songs. Which makes it sound like I’m not very fussy, but…

JUSTIN LEWIS:

No, I’ve got a list like that as well!

SHANINE SALMON:

But most of my new music comes from hearing a song somewhere, which I Shazam, and then find it’s either actually really old, or on TikTok. Certain songs will trend, and I think PinkPantheress is trending with ‘Illegal’ at the moment, you’re going to hear that a lot. The more the algorithm [recognises] this is a really popular song and video, it’ll get more viewers. I’ll try and find the exact name…

JUSTIN LEWIS:

Was it the Blow Records track?

SHANINE SALMON:

It was my understanding that it was put on TikTok because the lyrics are quite suggestive, although it’s in Portuguese, so if you played it to your Portuguese-speaking parent they’d be really shocked, because it’s over what sounds like an 80s disco track. And you think, ‘This is a really good song, but I don’t remember hearing it before’… My understanding is that it’s a rap song that’s gone through a filter process to sound like it was made in the 80s. The lyrics are kind of a song, but instead of making something new out of something old (like Fatboy Slim’s remix of Cornershop’s ‘Brimful of Asha’), this is like putting ‘Brimful of Asha’ through the AI and seeing what it comes up with.

That’s what I think is the more tricksy element of AI, because you’re going to go, ‘Well, why wouldn’t some musician hear this song and remix it?’ but instead they’re putting lyrics through… There are various processes.

Last year, I went through a period of being quite obsessed with Udio [AI music generator]. You can give it prompts, as you would with any other language module. So you could say, ‘I want a song about going to the fish and chip shop in the style of… jazz, or whatever. And you’d probably get more out of it with a Pro version, but: you’d get a two-minute song. And if you’re a lyricist but you can’t or don’t sing, or you don’t read music, you can put your original lyrics through that, and it’ll create a song for you. And then you send it to an A&R department or whoever now listens to new music.

So I think it’s got the potential to be a bit more dangerous, and we’re already seeing that with the mysterious ‘group’ Velvet Sundown.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

Yes, Velvet Sundown. When I prepare for each of these interviews, I put together a long playlist of everything we’re likely to discuss, everything the guest has suggested, and maybe a few surrounding tracks as well. And I’ll put that on while I’m working on other things. And so when the Blow Records track came on, I’d forgotten it was on your list, and I found myself thinking, ‘This is rather good, who’s this?’ And that really confronted my prejudices as an old person but also as a ‘creative’ person, so to speak. Because I had assumed I could spot AI-driven music, and maybe I can’t.

SHANINE SALMON:

Yeah, that’s been my shock because it was all over TikTok, I just liked it as a song, and then someone said, ‘Hang on, I’ve deep-dived, this song didn’t exist beforehand, and it’s only just been uploaded, and actually, if you look into it further, they’re not claiming it is a song from the 80s.’ They put their name on it, and I think they have admitted that they ran it through some software. What it actually says about the artist: there’s nothing on Spotify saying, ‘This might be AI generated.’ Whereas with Velvet Sundown, I think they added something recently after they did an investigation. How did they describe it: [Reads from Spotify description]: ‘Synthetic music project, guided by human creative direction and composed voice and visualized with the support of artificial intelligence.’ But they’re saying, ‘We’re not trying to trick audiences, we’re still providing, we’re still going through a process to create music.’

JUSTIN LEWIS:

And ‘they’ve’ released three albums just this summer.

SHANINE SALMON:

As somebody who uses AI a lot in work, I find myself wondering, ‘Is using computers to enhance stuff bad?’ That whole T-Pain kind of autotune – nobody sings like that, that’s not natural. You use effects on music all the time. But where it crosses a line is, for instance, what technology you’d have used to remix the Blow Records song. Remixes have always happened – Fatboy Slim with Cornershop, the Julian Raymond mix of Freddie Mercury’s ‘Living on My Own’ – but it’s always been made clear that ‘this is a remix’, that they’ve been given the rights to the song, so off they go.

With AI, it’s not clear actually. Does someone have the right to that song, to those lyrics? And also the legal element, and what happens to those genuinely creative people now? Anyone now can just put something through a computer and create a song, but they haven’t got a musical bone in my body. Like that’s scary.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

When I was listening to a Velvet Sundown album, I found myself listening out for the lyrics first and foremost, which are actually bollocks. There’s all these references – I counted them up – to sky, light, fire, wind, all very elemental, lots of stuff about shadows and silence. It’s not really about anything. There’s a complete lack of humour.

SHANINE SALMON:

Yeah. But I think there are so many musicians out there like that. I think Lewis Capaldi seems quite a fun, interesting person, so why are his songs so boring? So with that, maybe you’ve got a generation of sad young men for whom that’s potentially relatable. But that article I shared with you from Associated Press [dated 31 July 2025], which was saying that actually there are certain words that keep turning up in AI songs… like ‘neon’.

JUSTIN LEWIS:

Oh my god, yeah, ‘neon’. And all these attempts at oxymorons like ‘silent voices’ as if it’s trying to sound deep. [Laughter] And then I found myself thinking of examples of terrible, vague lyrics being spouted by real human beings over the years.

SHANINE SALMON:

With the Velvet Sundown albums in particular, I was thinking earlier about [the Italian pianist and composer] Ludovico Einaudi, because his stuff often has these wishy-washy titles, and I wouldn’t have been surprised if all these Velvet Sundown tracks had [started as] instrumentals. I don’t know if that crosses a line. There is some input, but what I think is happening is: whatever software or hardware you’re running it through, it’s going, ‘Yeah, we wrote a song for you last time that had “neon” and weird oxymoron titles, so that’s what you want, you downloaded that, you were happy, I’m just going to keep giving you what you want, because you’ve done that on time.’

I mean, I use AI in my work, I create assessments. I’ve flirted with it for quiz writing, particularly when I’m compiling buzzer quizzes, to try and work out where things should go, and in what order. But I found I had to refine it so much that it’s not really worth doing. I’d love to know who’s behind this, and what are they filtering down – if anything? Like are they looking at the output and saying, ‘This is terrible, can you get rid of that lyric or change the tune slightly?’

JUSTIN LEWIS:

Yes, how much of it is going through the editing process later?

SHANINE SALMON:

Yes, it’s not so much ‘What is AI?’ as ‘Where is the human?’

—-

Shanine Salmon’s extensive archive of her theatre reviews, View from the Cheap Seat, can be found here: https://viewfromthecheapseat.com

You can follow Shanine on Bluesky at @braintree711.bsky.social, on What Was Twitter at @braintree_, and on Instagram as @shanine_salmon.

——

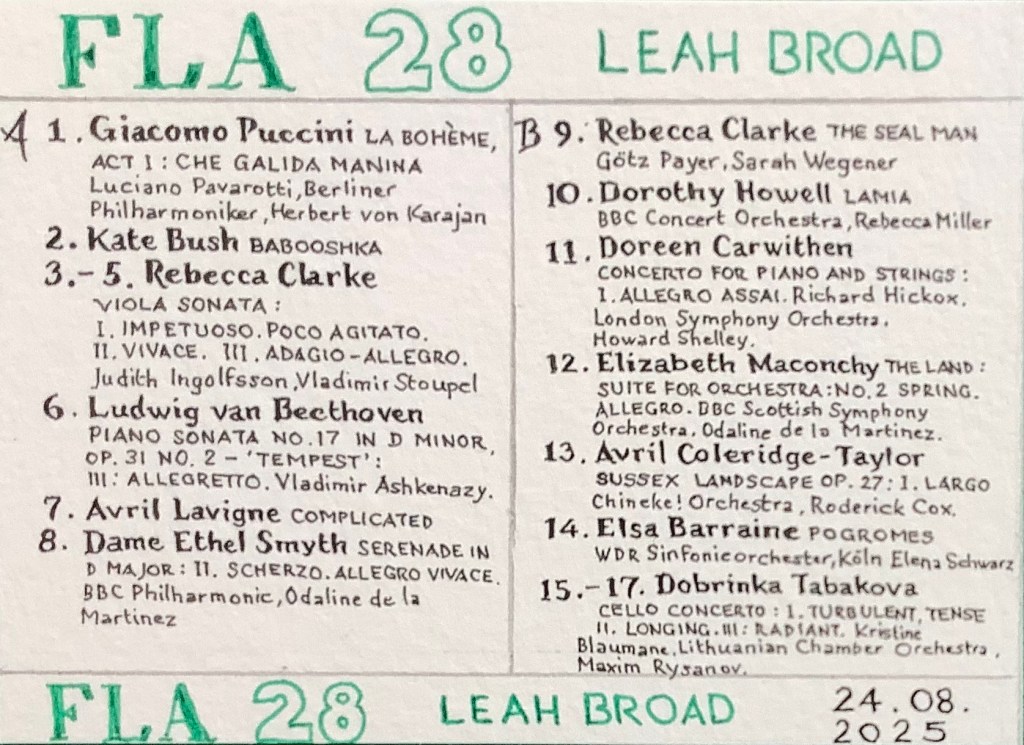

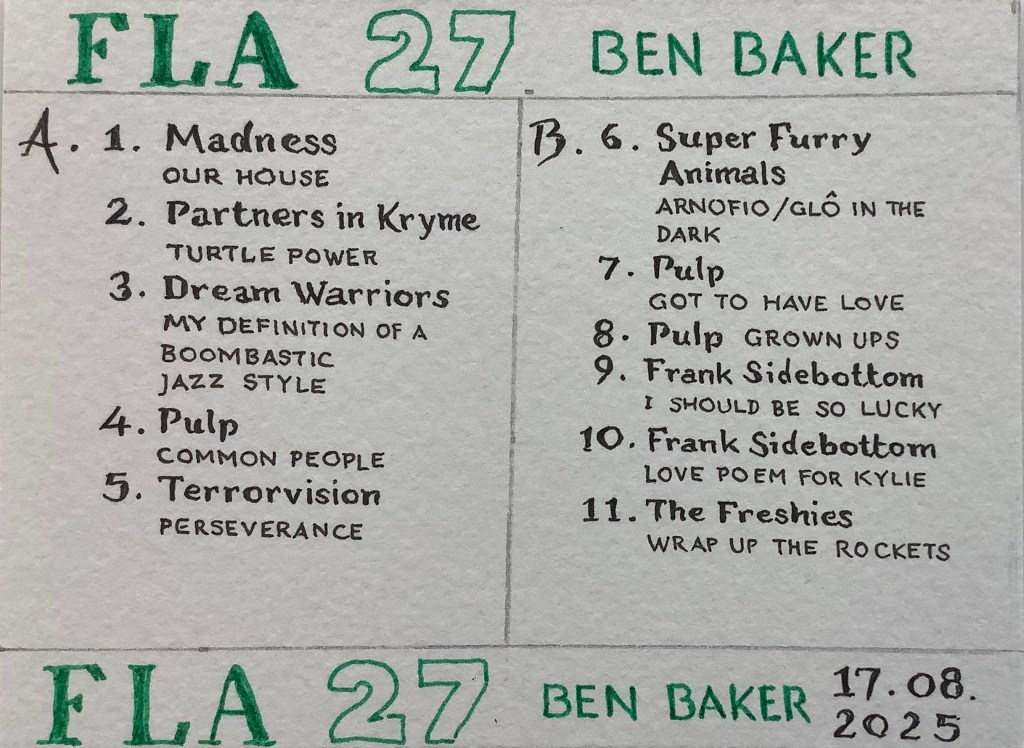

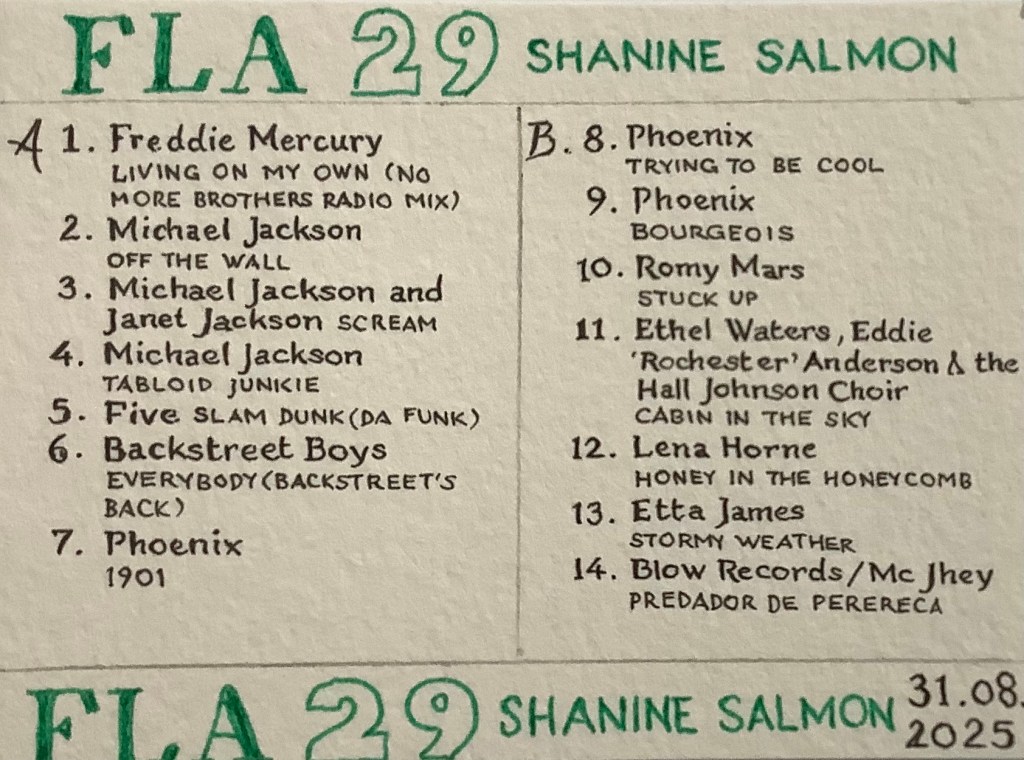

FLA PLAYLIST 29

Shanine Salmon

(For the time being, this site and project uses Spotify for the conversation playlists, but obviously I disapprove that Spotify doesn’t pay artists and composers properly, and other streaming platforms are available, as are sites to buy downloads and buy recordings. For consistency, you can also listen to the selections via YouTube (where available), and links are provided in each case, below.)

Thanks to Tune My Music, you can also transfer this playlist to the platform or site of your choice by using this link: https://www.tunemymusic.com/share/kyzUBBZp2k

Track 1:

FREDDIE MERCURY: ‘Living On My Own (No More Brothers Radio Mix)’: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SbWY5c-kJnw&list=RDSbWY5c-kJnw&start_radio=1

Track 2:

MICHAEL JACKSON: ‘Off the Wall’: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_BfcRjZn6y4&list=RD_BfcRjZn6y4&start_radio=1

Track 3:

MICHAEL JACKSON & JANET JACKSON: ‘Scream’: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0P4A1K4lXDo&list=RD0P4A1K4lXDo&start_radio=1

Track 4:

MICHAEL JACKSON: ‘Tabloid Junkie’: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=loCFx_eelXE&list=RDloCFx_eelXE&start_radio=1

Track 5:

FIVE: ‘Slam Dunk (Da Funk)’: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pNMgraIeUJc&list=RDpNMgraIeUJc&start_radio=1

Track 6:

BACKSTREET BOYS: ‘Everybody (Backstreet’s Back)’: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xPsiB9GlgKQ&list=RDxPsiB9GlgKQ&start_radio=1

Track 7:

PHOENIX: ‘1901’: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dLawb_TKWXQ&list=RDdLawb_TKWXQ&start_radio=1

Track 8:

PHOENIX: ‘Trying to Be Cool’: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LXBUnNWeqzc&list=RDLXBUnNWeqzc&start_radio=1

Track 9:

PHOENIX: ‘Bourgeois’: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HcsIYlYJ45A&list=RDHcsIYlYJ45A&start_radio=1

Track 10:

ROMY MARS: ‘Stuck Up’: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DSobFLenJVw&list=RDDSobFLenJVw&start_radio=1

Track 11:

ETHEL WATERS, EDDIE ‘ROCHESTER’ ANDERSON & THE HALL JOHNSON CHOIR: ‘Cabin in the Sky’: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cezhs6G2B60&list=RDcezhs6G2B60&start_radio=1

Track 12:

LENA HORNE: ‘Honey in the Honeycomb’: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LmvVIlOmxpo&list=RDLmvVIlOmxpo&start_radio=1

Track 13:

ETTA JAMES: ‘Stormy Weather’: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VE5_fDmPt0w&list=RDVE5_fDmPt0w&start_radio=1

Track 14:

BLOW RECORDS / Mc JHEY: ‘Predador de Perereca’: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vRBu_RLBt1A&list=RDvRBu_RLBt1A&start_radio=1