(c) Nina Hollington

In March 2020, almost the last event I went to for ages was the London-based launch of Philip Clark’s tremendous Dave Brubeck biography, A Life in Time, which subsequently won the Presto Jazz Book of the Year 2020. It’s been a while since we last met in person for a cup of tea to talk about music of all kinds, culture and other stuff, but in the spring of 2022 we did at least manage to do this over Zoom. During our conversation, not only did Philip discuss his First/Last/Anything choices, but also talked to me about his career in music, journalism and writing, including the beginnings of his next book on the music and culture of New York.

—

PHILIP CLARK

My dad is a painter. He studied at the Royal College of Art during the early 1960s with Peter Blake. Ian Dury was in his tutor group. He had, and still has, an impressive record collection and, when I was a kid, I didn’t recognise any musical divisions. I’d grab Schubert and try it out, I’d grab John Coltrane, I’d grab Bob Dylan. And my dad also had Stockhausen and Schoenberg, The Byrds, and for reasons he could never quite explain, lots of Jack Teagarden, the Classic jazz trombonist. Another item he had that really changed the course of my life was Dave Brubeck’s Time Out, which he painted to every night. The family mythology insists that I used to run into his studio and dance to ‘Blue Rondo à la Turk’, from the age of three or four. So that was the music that immediately resonated with me. My dad’s records seemed very exotic – sleeve notes about recording studios in New York and unpronounceable German names with a gazillion syllables. Although I grew up in 1980s Sunderland so pretty much anything seemed exotic.

JUSTIN LEWIS

So all this music seemed to carry equal weight at home, but then you’d go to school and it wasn’t like that at all. Never mind pop music, not even jazz would be on a syllabus. Do you remember there were furious complaints in the Radio Times, when Duke Ellington was Radio 3’s This Week’s Composer in the mid-80s [1985, in fact]? People not just saying, ‘Well, jazz isn’t really my thing’, but being actively furious.

PHILIP CLARK

And assuming that anyone would care they don’t like Ellington. That’s hilarious. There’s a lot of that in the classical world. Classical music should really open your mind, you should never stand still. But sometimes it narrows people’s minds. People focus on the thing they like with laser precision, which is fine, but they can lose sight of a wider culture picture. The classical world at the moment seems fixated on the idea of the ‘neglected’ composer, but without much critical discourse about why some composers dropped off the end of history. Hearing a lot of this stuff, I think, ‘yes’, history wasn’t wrong to cast someone like Ruth Gipps into the wilderness. I’ve talked to opera critics who have no interest I could discern in anything that happened before Mozart or after Alban Berg. Let alone any vocal traditions from other cultures, or traditions that grew up in the twentieth century alongside opera, jazz or rock singing for instance. How anyone could be interested in the art of singing and not be mesmerised by Bob Dylan’s voice – the sheer sound of it, and how it operates – is beyond me.

JUSTIN LEWIS

You’re that little bit younger than me – what do you remember about the music curriculum at school?

PHILIP CLARK

I remember an anthology of music that attempted to draw a line from the Renaissance onwards, but then petered out in the twentieth century. No Boulez, Stockhausen or even a relatively approachable composer like Britten. A bit of The Beatles, I think – ‘Eleanor Rigby’, which we were told with great fanfare used a string quartet and I thought, ‘So what’. There was an attempt to squeeze Indian music into the syllabus, but with a Western transcription of Indian music. Why they couldn’t bung on an original Ravi Shankar record, I don’t know. But I had a fantastic music teacher who knew he had to cover the syllabus but, at the same time, was listening to me improvise on the piano, me trying to copy Brubeck and Thelonious Monk. He started feeding me Bartok and Varèse, and those records opened things up exponentially.

Later I did music ‘A’ level at Newcastle College and one of my best friends there was the conductor John Wilson, who I hooked up with again once I’d moved to London in 1994: we happened to be living in the same neighbourhood. I’ve fond memories of that time. I was composing. I was also a pianist, and then I was a percussionist, playing in various wind orchestras and brass bands. I became very aware that music is good at teaching you to become a social animal. Playing in youth orchestras was the first time I’d met girls, outside my own family.

JUSTIN LEWIS

Yeah, it was one of the best things for me as a teenager. Orchestra was half-boys, half-girls, roughly.

PHILIP CLARK

You know you’re part of a collective, you’re responsible for your tiny little bit, and if you screw up, it affects everybody else, and that’s an important lesson. As a pianist you are on your own, but playing percussion, your sense of rhythm has to snap into place. Where you place the second beat of the bar really matters. Playing percussion was the best step I ever took in terms of developing my musicianship.

—

FIRST: LEONARD BERNSTEIN: West Side Story (1985, Deutsche Grammophon)

Extract: ‘Cool’

JUSTIN LEWIS

Talking of collaboration, it’s a good moment to talk about Leonard Bernstein’s mid-1980s recording of West Side Story. In preparation for this, I rewatched the ‘Making Of’ documentary with Bernstein and Kiri te Kanawa and José Carreras. And I don’t think I’d seen it since it had been on, originally. [Omnibus, BBC1, 10/05/1985: Kiri Te Kanawa – The Making of West Side Story Documentary – YouTube]

PHILIP CLARK

It’s just astonishing, isn’t it? My music teacher at the time brought it into school on a VHS tape. I was thirteen. It was the last day of term. Seeing Bernstein, this guy in a red jumper… He seemed like a magician. Making all these musicians pull these tricks, shouting at them when they got it wrong, the ecstatic joy when everything slotted into place. I was transfixed.

JUSTIN LEWIS

When I watched it, I’m not sure I’d even seen the original film at this point, but I still felt I knew all the songs. And the orchestra on the recording of this was a contracted orchestra, they hadn’t worked together before, right?

PHILIP CLARK

They were handpicked players that Bernstein knew from the New York scene, from the New York Philharmonic and elsewhere. The question West Side Story raises immediately: what exactly is it? You need a good classical string section, but then, can a classical trumpeter really nail those jazz parts? Not necessarily. So immediately you’re into the idea of creating, by necessity, a piece-specific ensemble, which I find really interesting.

JUSTIN LEWIS

And Bernstein himself using the word ‘funky’ to describe the work.

PHILIP CLARK

Well, he’s right!

JUSTIN LEWIS

Because you can’t categorise it, and why would you want to, obviously!

PHILIP CLARK

Throughout my life, I’ve been interested in music where precisely you don’t know what it is. An argument about West Side Story persists – ‘is it a musical, is it an opera?’ But not being able to define it opens up the space musically. The fact that Bernstein, in his symphonies, and also Tippett and Messiaen in theirs, were willing to pose the question, ‘But can this be a symphony; and if it’s not, what is it?’, seemed more intriguing to me than composers adding to a pile of recognisable pieces called ‘symphonies’, like they’re buying into a franchise.

JUSTIN LEWIS

The documentary is a brilliant, accessible way of showing you the method and the process. There’s not that much interviewing outside the recording session, they just let the session speak for itself, but in one bit Kiri te Kanawa says about how Bernstein was setting the tempo himself, and she says, ‘It’s like having a Mozart in the room.’ A luxury you don’t get that often, and another reason why living composers are so essential because they know how it should be played, or at least are there to guide you.

PHILIP CLARK

Bernstein has been heavily criticised for getting the tempo ‘wrong’ and there was a controversy about Carreras having the wrong voice to sing the part. Whatever. But when I was in New York a couple of months ago, to beat the jet-lag on the second night, I went to see the new film of West Side Story.

JUSTIN LEWIS

Oh – which I still haven’t seen yet!

PHILIP CLARK

The only cinema showing the film was on 65th and Broadway, where Lincoln Centre is, and practically the first thing you see in the film is an old New York street sign for 65th and Broadway, because West Side Story is set where the Lincoln Center is now. When you see the songs in context, the whole piece knits together. There are some songs – like ‘I Had a Love’ – which I wouldn’t necessarily listen to outside that context – but then others that I would. Apparently, ‘Cool’ was inspired by Bernstein going to a jazz club and hearing the alto saxophonist Lee Konitz, who was very famous for inventing long improvisational lines that curled around each other. The piece is layered like a cultural lasagne. There’s Latin stuff, and Bernstein’s incredibly specific use of jazz – he doesn’t just use a generic jazz style – he’s very careful about the different types of jazz he alludes to. Then there’s Stravinsky, there’s Copland, and you can almost trace every single note back to some other source, to Mahler and even Gilbert and Sullivan. Yet it all sounds like Bernstein. I’m still very attracted to composers who allow different musics to coexist within a piece. Bernstein uses that augmented fourth in the opening bars of West Side Story as a motif throughout the whole thing, a real unifying anchor, with a rigour that would have made Schoenberg proud.

JUSTIN LEWIS

And what did West Side Story lead to next, for you?

PHILIP CLARK

Anything with Bernstein’s name on it, I hoovered it up: Mahler, Beethoven, Stravinsky, Bach, Elliott Carter, his various collaborations with jazz musicians. When I interviewed Will Self, he told me that from his own parents’ record collection, he liked the Schubert String Quintet and the Miles Davis Quintet the most. So he thought the music he liked was ‘quintets’. Every record with the word ‘quintet’, he sought it out, no matter what it was. I was the same with Bernstein. I’d scour the second-hand record shops.

JUSTIN LEWIS

You’re trying to make patterns, I suppose.

PHILIP CLARK

You don’t really have the connecting tissue to work with at that age, especially pre-internet. Bernstein was definitely a starting point then, and remains hugely important to me now, in terms of being a conceptual thinker who was able to put different sorts of music together, without fusing them. If a piece is chugging along in a recognisable style, throwing something else into the mix creates a fantastic tension, and why resolve that tension? West Side Story resolves harmonically, sort of, at the end, but in another way it’s a mess – and I don’t mean ‘mess’ pejoratively. The different styles stick out, attack each other. Then if you think of what the piece is about…

JUSTIN LEWIS

Because the city is a complicated, interesting ‘mess’ of styles.

PHILIP CLARK

And gang tensions within a city, and I feel that cities aren’t really about resolutions. Fundamentally, I have to say, I dislike musicals. When Sondheim died, I tried a couple of things, but I had to switch them off. So mawkish and emotionally manipulative, a peculiar, faked profundity. I’m not that interested in music that tells a story. I’m into in music because of sound, and the least interesting about West Side Story for me is the plot. What really interests me is the deeper story of what’s going on in the body of the orchestra, inside the fabric of the music, and how Bernstein builds conversations between different styles of music. Bernstein’s Mass, first performed in 1971, is a real pivot moment for twentieth-century music. At the beginning it sounds like Luciano Berio, with atonal electronic fragments dispersed around the speakers, and then, suddenly, a guitar chord leads into a song that’s pure Simon and Garfunkel; and there’s marching bands, rock bands, jazz bands, atonal orchestral writing and carefully worked out montage and collage. Every-fucking-thing is there, and in terms of compositional consistency it doesn’t even begin to work. But that’s not what Bernstein was trying to achieve. It’s a meta-modernist construction of different styles that I find very truthful.

When I was in the thick of writing music journalism, I became known as someone who wrote a lot about central European modernism – Boulez, Stockhausen, Xenakis, Kagel, Ligeti, Lachemann, Cardew, Messiaen, Donatoni et al – and when I’d write about my love of Bernstein some people would think I’d lost the plot. I even had emails on the subject: I remember an especially condescending one from a leading British composer, who shall remain nameless, who told me I was letting the side down. Well, screw him. Bernstein fits the pattern: a composer not just ‘doing’ music but asking questions about what music can be. What happens when you put the fabric of music under the microscope, and investigate it?

—-

LAST: MORITZ WINKELMANN: Beethoven/Lachenmann (Hänssler Classics, 2022)

Extract: ‘Marche fatale’ (Version for piano)

PHILIP CLARK

Radio 3 was, of course, an education in itself. It was through Radio 3 I first heard about, for instance, Morton Feldman and Peter Maxwell Davies, and also Michael Finnissy who would later become my teacher. I’d tape Music in Our Time programmes, what Radio 3 called their new music programme during the 1980s and ‘90s, obsessively. And I also discovered Helmut Lachenmann through Radio 3. I was immediately drawn to his soundworld, although it was only when I did my undergraduate degree at Huddersfield University that I was able to lay my hands on some scores and properly grapple with Lachenmann’s music and approach.

Lachenmann, like Bernstein – not a sentence you’ll hear often – is interested in questions of musical identity. He is famous for orchestral textures that whisper and seem to exist on the very point of crumbling, as though making a point that structures composers have inherited from the nineteenth century, even the earlier twentieth century, can no longer stand up for themselves. Lachenmann’s music is at the same time very elemental, but also incredibly refined and strikingly beautiful, like a fine-spun thread. He has unpicked ideas of conventional instrumental technique; conventional technique might dictate that a violinist puts their finger at a certain position on the fingerboard to produce a certain note or effect. But what happens if the same violinist puts their finger one millimetre to the left? What does that do to the sound? That is the wildest of simplifications of course, but think about a situation in which Lachenmann asks, say, thirty violinists in an orchestral piece to play one of these extended techniques. If just one of them puts their finger in slightly the wrong place, this carefully worked-out sound is lost. So Lachenmann deals in a whole other sort of preciseness.

JUSTIN LEWIS

It’s surprising how just changing something just a tiny bit, in any artform, can result in something new.

PHILIP CLARK

By imposing yourself in the cracks of normal technique a new kind of musical experience can be found. Improvisers know this, and jazz musicians know this, and rock guitarists who distort sound know this. In Lachenmann’s other piece on this disc, ‘Wiegenmusik’, the music seems to inhabit the resonances and the sustains rather than the hitting of the notes, which becomes somewhat incidental.

JUSTIN LEWIS

Of Lachenmann’s work I only know the two pieces on this disc, so far, both of which I really liked. What would be a good orchestral piece that demonstrates something like what you mention?

PHILIP CLARK

His piano concerto, ‘Ausklang’, would be one. It’s a mammoth fifty-minute piece for piano and a massive orchestra. There are a few moments when it erupts, but most of it dwells in a hinterland between moderately soft and moderately loud – soft louds, and loud softs – with intensely subtle deviations of texture and sound. It took him decades to work all that stuff out, and it’s a real triumph of what someone can do with musical notation. You take relatively conventional annotation, tweak it a bit, and get musicians to behave in a completely different manner and change their habits. Fantastic.

—-

JUSTIN LEWIS

So how did you get into writing about music in the first place?

PHILIP CLARK

I had rent to pay! I was a composer, I had a teaching job for a year which I absolutely hated, and then I won a composition competition held by Classic CD magazine. This was before email, so I faxed the editor of Classic CD to say, Dave Brubeck – who I already knew a little bit – is touring the UK, and I’d be interested in interviewing him, if he’d like an article. He said yes. To this day I remain convinced he thought I was somebody else and got the names muddled. Anyway, I submitted the article and then he rang a week later and said, ‘What are you doing for us next month?’ So I wrote a piece about Charles Mingus and it snowballed from there. Classic CD led to a magazine called Jazz Review, which led to The Wire, which led to Gramophone; and years later to newspapers and, eventually, the London Review of Books. I was starting to make a living, and then a decent living, but that was never my intention.

JUSTIN LEWIS

I wanted to ask you about the kind of music criticism you’ve written. I sort of understand how pop music criticism works – I’ve done that a little bit myself – but I wouldn’t know how to write your kind of analysis, especially about a new piece of music.

PHILIP CLARK

Depends really. I wrote about a lot of standard classical repertoire during one period, which requires a very different approach from new composition or improvised music. With standard repertoire, there are certain givens about whether, say, Simon Rattle does Brahms 3 slower or faster than Herbert von Karajan. He either does it faster or he does it slower, and that’s that. And from those givens you have to extrapolate interpretative ideas about how a conductor is dealing with a piece; how they are dealing with structure, and the relationships of material within a movement. Is the conductor working within a tradition? Is the conductor trying to push a piece away from the tradition with which it’s most associated, taking a revisionist view? Are they being faithful to the music? Are they disrupting the music?

Then there are technical questions. How successfully are they balancing the sound within the orchestra. Can you hear everything? Some composers, though, think in terms of layering the orchestration, each layer adding to the whole. Is the conductor simply emphasising a melody line, and losing everything else?

But with a new piece, all that becomes secondary. Hearing a premiere, I want to be entranced by the composer’s inner-imagination. Is he or she merely re-mapping – or simply cribbing – some model that already exists? Using familiar landmarks, in exactly the place where you would expect to hear them? Or is this composer trying to do something more daring, really challenging their own pre-conceptions, dancing with the unknown?

Harrison Birtwistle, who died a few weeks ago, his ‘Tragoedia’, essentially his Opus 1, encapsulates everything he did over the next fifty years, like he wrote one big piece from the 1950s to the end of his life, observing the same material from a million different angles, finding things that work in microcosm in one piece which he then allowed to blossom in the next piece. With ‘Tragoedia’ everything is in there: orchestration, harmony, the way the harmony informs a structure. I’ve been dealing with Elliott Carter’s music again recently after a long time. The music he wrote during the late 60s, you hear him grappling with his material, like he’s trying to find the technique he needs to write the piece through the experience of writing the piece: the ‘Concerto for Orchestra’ and ‘Double Concerto for Piano and Harpsichord’ in particular. By the mid-70s, though, he’s worked out the music he wants to write, and of course it works, and the technique is supremely fluid, but I find the pieces far less engaging, and sometimes just boring.

One of the reasons I stopped doing classical music journalism was that, after twenty years, I came to care less and less whether Rattle’s Brahms 3 is faster than George Szell’s. There are bigger cultural issues with which to deal. At a time when classical music is being squeezed inside all sorts of culture wars, and major labels are issuing absolute crap that masquerades as classical music, and the prevailing culture often seems positively hostile – let’s not even mention that dipstick Nadine Dorries and her attacks on the BBC, and the asset-stripping of arts courses from schools and universities – the classical music press here often feels dismally supine and unengaged, carrying on like it’s business as usual. Where’s the anger? The itch to question where classical music has come to stand within our culture compared with where it was even twenty years ago? If I was them, if my whole life was about classical music, I’d be worried and want to take some sort of stand.

—–

ANYTHING: DAVE BRUBECK: We’re All Together Again for the First Time (1973, Atlantic)

Extract: ‘Truth’

JUSTIN LEWIS

Let’s talk about your Dave Brubeck book, A Life in Time. Award-winning, acclaimed and rightly so. In the introduction, you mention you were in Spain on holiday. There’s something about buying a record on holiday – I think often your mind is somewhere else.

PHILIP CLARK

Yes, it was a family holiday. I was 16 or so. We had just visited the Salvador Dali Museum in Figueres, and I’d bought this cassette in a second-hand record shop nearby, which we put on in the car. And the sound and energy of the first track, called ‘Truth’, pulled me right in. I’ve thought about and analysed and intellectualised what the music does since – probably too much! – but back then it was: ‘Shit! What is this?’

JUSTIN LEWIS

When I was listening to it, it felt like a very long way from what I thought I knew about the earlier recordings.

PHILIP CLARK

Yes and no. If you go back to the Brubeck of the mid-50s, when he was recording for Fantasy Records, before moving to Columbia, the Fantasy guys were quite happy to record concerts and release them more or less unedited. Those early records contained huge, long improvisations – a quarter of an hour on standards like ‘These Foolish Things’ and ‘The Way You Look Tonight’. Brubeck’s solos are extraordinary, the way he darts between romanticism, Bartók-like clusters and stride piano – finding ways to allow different things to coexist within a piece of music. His disjoints, his mismatches and the cross-cutting between different styles stood in complete contrast to the bebop pianists – who were all about sustaining the flow of the energy and keeping the momentum on the move.

Dave’s solo in ‘Truth’ opens in very strict jazz time, then, after a little while, the left hand deviates just slightly, and then the left hand and the right hand move apart. Countable time and pulse fizzle out and he ends up floating on a slipstream of sound. The harmony accrues clusters of notes and Dave’s chords get thicker and denser, and the pulse crumbles even further, and a point is reached where you think, he just can’t go any further. Yet he keeps on pushing further and further – obstinately and wilfully. When we got home from holiday, I ran to the piano and started testing these same kinds of clustery sounds, making them for myself. When I played them to my piano teacher she was absolutely horrified. ‘Those sounds don’t exist’ – those were her exact words. Yet I had recorded proof that they did, and that indeed I could do them. Within a week of hearing that Brubeck record, I was checking out Cecil Taylor and John Coltrane and Albert Ayler and Ornette Coleman. Free jazz opened up for me. And also Stockhausen and Boulez and Varèse; just the sound of that Dave Brubeck record changed everything for me.

JUSTIN LEWIS

And obviously on that same record there’s a much longer version of ‘Take Five’ than most people will be familiar with.

PHILIP CLARK

Sixteen minutes. The first ‘Take Five’ from 1959 established a white canvas for future explorations. They just about managed to get through it in ‘59. It’s edited very heavily. Dave puts the vamp down to keep the quartet together, and sounded rather nervous doing so, because it kept falling apart. But that 1972 version, in contrast, is positively anthemic. The same vamp that had been holding the piece together in 1959… as soon as he starts playing it, the audience go crazy. ‘Take Five’ is in E flat minor, and Dave, in his solo, plays in the major over the chords. The left hand keeps the ‘five’ going, but he’s superimposing four and three over the top. Really he’s playing everything but 5/4 and E flat!

That performance roars towards a fantastic drum solo by Alan Dawson. Joe Morello, the drummer during the years of the ‘classic’ Dave Brubeck Quartet, came out of big band and swing. But Alan Dawson, who essentially took Joe’s place, was more of a free jazz drummer by instinct. Before joining Dave, he’d played with Sonny Rollins and Jaki Byard, and brought a free jazz energy to the Brubeck group. Listen to the way he plays against Dave’s vamp at the beginning. He spring-loads the beat – like he’s on tiptoe. By the 70s, Dave could do whatever he wanted with ‘Take Five’. So long as he played that vamp at the beginning, he could play as free as he liked. I asked Dave later, ‘Do you ever get tired of playing it?’ And he said, ‘No, it becomes a gauge of where we are as a group every night.’ Every night, they’d view it from a different angle. He knew how to keep it fresh.

JUSTIN LEWIS

It’s an ideal position to be in, though to have a piece like that where you can play it every night and you’ll never get bored of it because there’s always something interesting and fun in it.

PHILIP CLARK

It’s infinitely flexible. That oscillating two-chord vamp – you can do anything with it – put anything against it. It’s going to work.

—-

JUSTIN LEWIS

You’re very interested, aren’t you, in how all these elements coexist in the context of a city.

PHILIP CLARK

Indeed. Take London, in the mid-1960s, for instance. I’m passionately interested in free improvisation, this British musical movement that emerged around 1964/1965, mainly in London, although other things were happening around the country. In 1965, you have the start of AMM – Eddie Prévost, Keith Rowe and various other people – who were all interested in jazz, but also trying to come up with an authentic homegrown idea of what improvised music in this country could be. They workshopped their music at the Royal College of Art. In Covent Garden, there was a little venue called the Little Theatre Club, which is where the Spontaneous Music Ensemble found its feet, and they were, again, trying to deal with the aftermath of jazz. The guitarist Derek Bailey came to London at the same time, who also came out of jazz, but also Anton Webern. All this activity is happening around free improvisation. But around the same time, in Muswell Hill, The Kinks were starting – and they were dealing with this exact same question. How to place American culture within a British or London context. If you’re interested in The Kinks, how could you not be interested in free improvisation. Equally, if you’re interested in free improvisation, how can you not be interested in The Kinks? Yet very few people seem interested in both, but these are the connections I’ve always tried to make in my journalism and in my work.

JUSTIN LEWIS

Not only have you just worked with Dave Davies of The Kinks on his new autobiography, but also that you’re currently working on another book, this time about New York with a vast array of figures, that draws on different styles, different periods, but is designed to explore a big city of culture and how it can be all sorts of things.

PHILIP CLARK

It’s called ‘Sound and The City’ and it’s about what makes New York sound like New York, and not Paris, Berlin or London.

JUSTIN LEWIS

Or even another American city.

PHILIP CLARK

Indeed. The book deals with external factors like immigration, geology and architecture, which turn out not to be external at all. Edgard Varèse arrived from France, where all the music he wrote was destroyed – we don’t know any of it – but the impression left from contemporary reports is that it was hyper-romantic Richard Strauss, perhaps with a few illegal harmonies and sexy flourishes. Then he arrived in New York in 1916, and immediately became interested in the sound of sirens. But he didn’t use the orchestra to replicate or evoke a siren; he literally took the siren from the sidewalk and slammed it into the orchestra. The exterior becomes the interior. The physicality of New York imposes itself on people’s understanding of what they think music is and changes it. John Cage, Debbie Harry, Ornette Coleman, Television, Meredith Monk, William Parker: how are all these different musical personalities unified by the experience of New York, that’s what I’m exploring. I said earlier that I don’t believe cities are about resolution, but they are places where different musics find space to exist. I’m six months into what will be a three-year writing project, but already I’m gaining understanding of an underlying attitude towards music-making in New York; I’m beginning to perceive a lineage between say, Varèse and Wu-Tang Clan, and that attitude is more important than musical idiom or style.

JUSTIN LEWIS

I can remember getting The Best of Blondie for Christmas when I was 11, and there was this free poster, which went straight on the wall, of Debbie Harry wearing a T-shirt which read, ANDY WARHOL IS BAD, and I had no idea who Andy Warhol was at that point, but it immediately gave Blondie even more hidden depths. And it turned out that she had quite a past, she was already nearly 35. She had this music career going back to the late 60s, the world of psychedelia.

PHILIP CLARK

And after Blondie ended the first time, Harry started doing a lot of freeform jazz vocal improvisation, with the Jazz Passengers. Absolutely fantastic. The whole Blondie persona was just chucked out the window. Cross-fertilisation does happen in other cities, and that’s for other books, but with New York, the physical experience of being in that city does something to musicians’ sense of structure and pacing and the material they use. I want to find the unifying thread that links Edgard Varèse to hip hop, John Cage to Lou Reed. In Manhattan you’re forced to deal with this overload of sound, whether you want to or not. You’re on a compressed landmass, with these big buildings. The geology means they can sit there. So I’m not going to say the city is built on rock ‘n’ roll – but it is certainly built on rock! [Laughter]

—

Philip Clark’s Dave Brubeck: A Life in Time is published by Headline. He worked with Dave Davies on his new autobiography, Living on a Thin Line, which was published in July 2022.

Philip’s next book, which we discussed at some length during our conversation, is titled Sound and the City, and is due for publication in September 2026. See here for an article he wrote when he visited New York as part of the book’s background research: https://blogs.bl.uk/americas/2022/04/sounds-of-new-york-city.html

He is represented by Curtis Brown: curtisbrown.co.uk/client/philip-clark.

You can follow Philip on Bluesky at @musicclerk.bsky.social.

—-

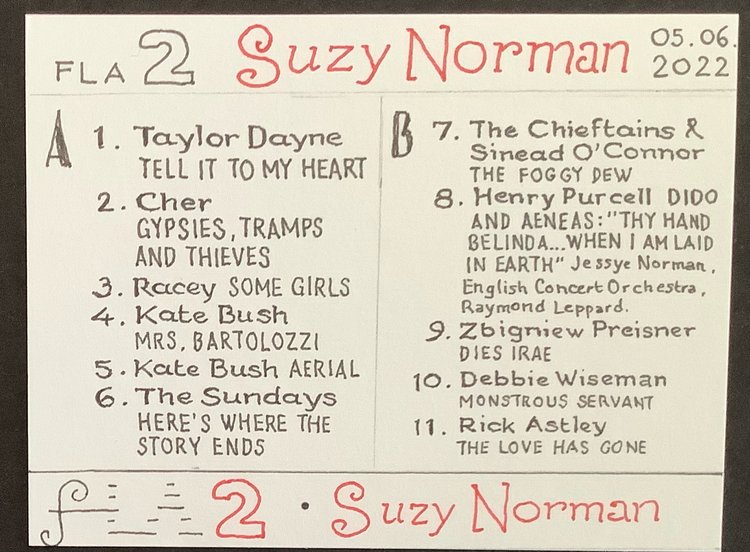

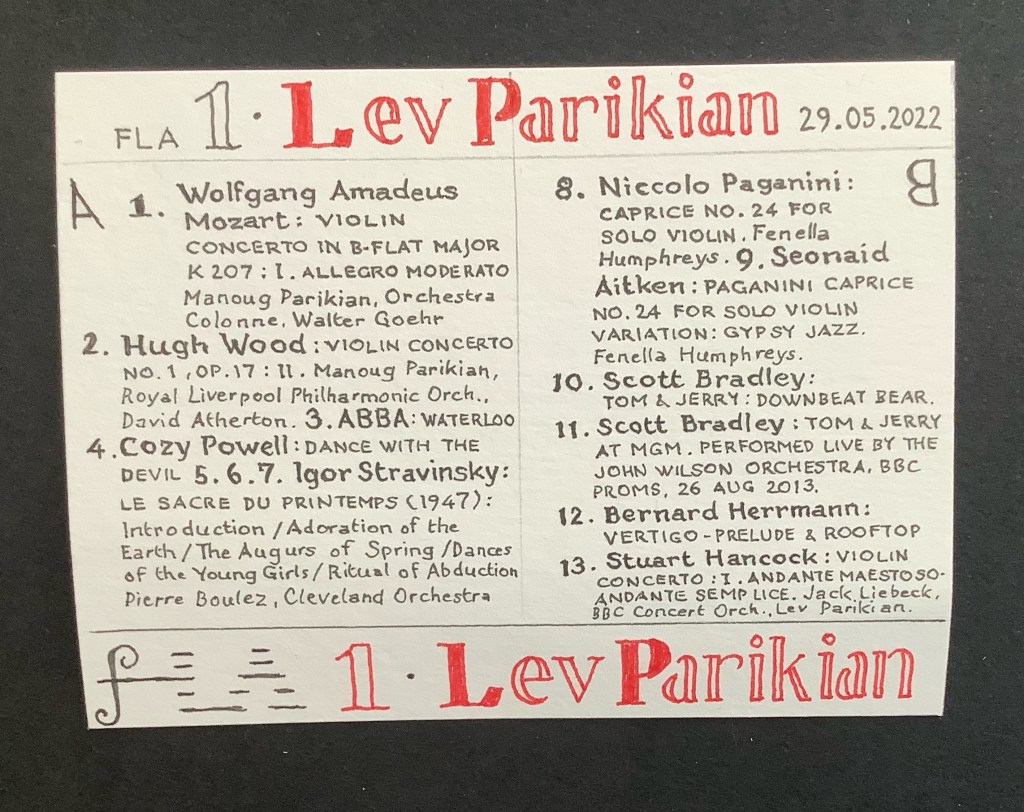

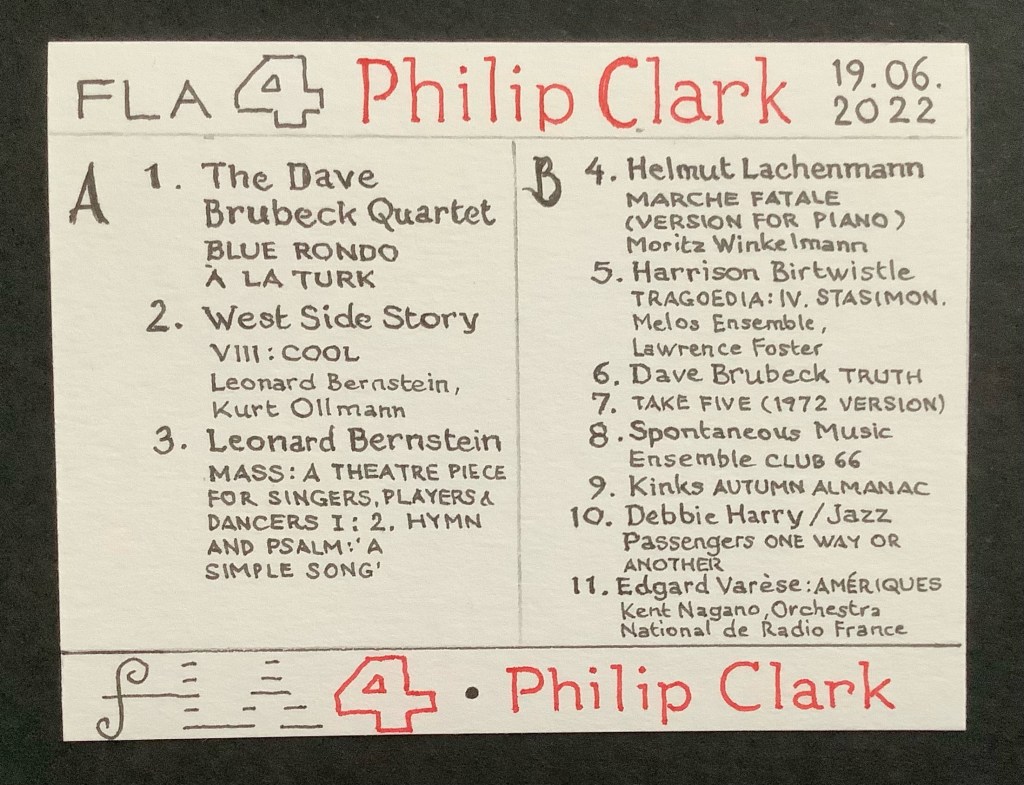

FLA PLAYLIST 4

Philip Clark

(For the time being, this site and project uses Spotify for the conversation playlists, but obviously I disapprove that Spotify doesn’t pay artists and composers properly, and other streaming platforms are available, as are sites to buy downloads and buy recordings. For consistency, you can also listen to the selections via YouTube (where available), and links are provided in each case, below.)

Track 1: THE DAVE BRUBECK QUARTET: Blue Rondo à la Turk: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vKNZqM0d-xo

Track 2: LEONARD BERNSTEIN / KURT OLLMANN: West Side Story: VIII. Cool: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-w_7oM3Ohs4

Track 3: LEONARD BERNSTEIN: Mass: A Theatre Piece for Singers, Players and Dancers I:

2. Hymn and Psalm: ‘A Simple Song’: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VEcgy5vUtHI

Track 4: HELMUT LACHENMANN: ‘Marche fatale (Version for Piano)’

Moritz Winkelmann (piano): https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kDXOBeckLpo

Track 5: HARRISON BIRTWISTLE: Tragoedia: IV. Stasimon

Melos Ensemble, Lawrence Foster: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GMwVxNxKHK8&list=PLB0TfWlJAdxZ3Zyu042uAZZIsnS7ldkdV&index=138

Track 6: DAVE BRUBECK: Truth: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=n7E_AaGa9cE

Track 7: DAVE BRUBECK: Take Five (1972 version): https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Gt9sLIqQUkA

Track 8: SPONTANEOUS MUSIC ENSEMBLE: Club 66: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Gz1xWcusg48

Track 9: THE KINKS: Autumn Almanac: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=N3VDATV6dmY

Track 10: DEBBIE HARRY, JAZZ PASSENGERS: One Way or Another: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=t-xODrjOtnU

Track 11: EDGARD VARESE: Varèse: Amériques: Kent Nagano, Orchestra National de Radio France: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=P6E3pD8Uhtg